How the water shortage in China brought the Arab spring

The story of the revolutions in North Africa, the Levant and the Arab peninsula looks clear, at least at first sight. Repressive regimes, a lack of equal access to education and perspectives for development leading to desperation - all of this has brought events that look like a delayed echo from the processes of democratisation in Eastern Europe of the 90s. But another remarkable dynamic also deserves attention: the interaction between regional instability, the global grain market and the piling effects of climate change that have affected these continents.

The story begins in 2010. The grain output in Russia suddenly dropped by a third, compared to the usual levels, due to drought and fires. Meanwhile, in Canada and Australia the output suffered due to heavy rains. In China, the world's largest exporter and consumer of grain, a massive drought of unprecedented scales happened at the end of 2010, and China had to import grain from other countries. In result, the grain prices at the world markets jumped more than two-fold for the period between mid 2010 and the first months of 2011. The peak was in March 2011, just shortly before Mubarak was deposed in Egypt.

The thing is, the globalised food markets are now connecting otherwise geographically distant societies in ways never seen before, and not always with positive effects. This way, the climate cataclysms in China, Russia and Canada have directly reflected on North Africa and the Middle East.

A massive recent research by the Center for American Progress came up with an analysis of the effects of climate change and the food security on the Arab revolutions, looking for answers to the question how the chain of seemingly unrelated events has directly affected the turbulent transformations in societies like Egypt, Libya and Syria.

So what is the significance of the Chinese drought, the Russian fires and the Canadian floods for the Arab world? Let's take the Egyptians, who receive roughly a third of their calorie intake through consuming bread and related products. Nearly 40% of their household income is spent for food on average. Doubling the grain prices in 2011 meant that the price of bread soared, and this lead to food supply problems. In combination with the overall political instability, this in turn lead to social unrest and a revolution that, I would say, is still ongoing as we speak.

Among the myriad of reasons for the Algerian unrest in January 2011 was also the high price of sugar, milk, cooking oil and bread. Everything quickly escalated when the state media were compelled to admit that two protesters had died and hundreds had been injured during the first protests. At the same time, in neighbouring Tunisia the protesters were waving French toast against the security forces, a very eloquent gesture.

Syria was the place where this aspect of the protests was particularly well pronounced. For the last five years the country has gone through the longest period of drought in its recent history. More than 800 thousand people lost their means of living. 200 thousand were forced to leave their homes in the Aleppo region alone (which is the most seriously affected by the civil war). As for climate-change induced water shortage, in the Levantine region the connection between access to water (or lack thereof) and social and political unrest is always very direct and immediate. We all know how the Syrian revolution started, and how access and control of fresh water affects events and processes in the West Bank.

Such crisis situations are particularly dangerous for that region of the world because of the chronical shortage of water throughout most Middle Eastern and North African societies (which, on top of all that, are extremely dependent on food imports - in fact Egypt and Algeria have consistently been among the largest grain importers in the world).

The global climate change, whoever or whatever is the cause for them, may not be the primary reason for the revolutions in the Arab world, but they certainly emphasise the aggravating factors, which, in the conditions of already existing internal tensions and conflicts, often become the spark that ignites the powder keg.

The rising food prices (now called "agflation", from agrarian + inflation), is a result of a snowballing process: rapid population growth, coupled with depopulation of the rural regions and accelerating urbanisation, and shrinking of the arable lands and deteriorating crop diversity due to climate change - and from there, rapid increase of the food prices. In the circumstances of a globalised food market, and at a time of turbulent political change, these seemingly unrelated scenarios mutually intensify each other, undermining the regional stability in certain regions, and putting countries with weaker state institutions and civil society at extreme risk.

The fact that both politicians and scientists are already well aware of this chain reaction, is indeed a step towards a better understanding of such crisis scenarios (which is not to say that universal solutions for them have been found yet - and indeed, there may be none). Because, if the delicate system of food production is somehow tilted out of balance, there is a real threat for many more countries succumbing to chaos, the way the Arab region did. The World Bank and a number of reputed experts in the field are concerned that in case of rapid growth of the food prices, similar conflicts could erupt in Central America and the Caribbean, and in various parts of Africa like Uganda, Niger, Mozambique and Mali (yet again). And also in Central Asia, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

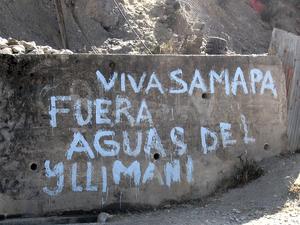

There is a good reason that these forecasts are already being actively discussed at the US Department of State and in various international humanitarian organisations. And there are mounting investigations on this subject. For example, a research from the beginning of this year analysed the relation between climate change, migration flows and the issues of national security in the Andean region. And there again, some interesting chain reactions were observed. Until 2050 the melting of the Andean glaciers is expected to negatively affect nearly 50 million people in Peru, Brazil and Bolivia, because fresh water will become extremely scarce in the dry seasons (we have already witnessed social unrest triggering a major political shift in Bolivia, exactly due to a crisis with water supply).

If we add the intensive development of industrialised agriculture, which is related to exponentially expanding arable land at the expense of the tropical rainforest, the end result, apart from the grave environmental impact this is having on the global climate, is that many people from the rural areas would be forced to work illegally, primarily in the thriving coca industry that is aiming at the rapidly growing Brazilian and European markets.

It has become clear at this point that the outdated traditional political strategies of the 20th century are no longer adequate enough to effectively tackle these problems. Unfortunately, no comprehensive plan for ensuring food and water security has been put forward for the time being, and neither have we witnessed the creation of a policy that would take climate change and its effect on regional conflicts in consideration in a comprehensive way. Right now we are only at the beginning of the discussion about a global policy that would be shared by most players that would make a difference, and which would potentially guarantee more stability in this increasingly volatile 21st century. The events in the Arab world show us how urgently needed it really is.