Russian political strategist talks about organizing Crimea, Donetsk referendums

A few days ago, Gazeta.ru published an interview with a Russian political strategist who helped to organize the independence referendums in Crimea and Donetsk Oblast. He spoke on the condition of anonymity, which allowed him to be unusually candid about what happened in there. That is not to say he's completely unbiased - it's pretty clear exactly what he thinks about the Ukrainian Crisis. But it's still a very revealing account you probably wouldn't get anywhere else.

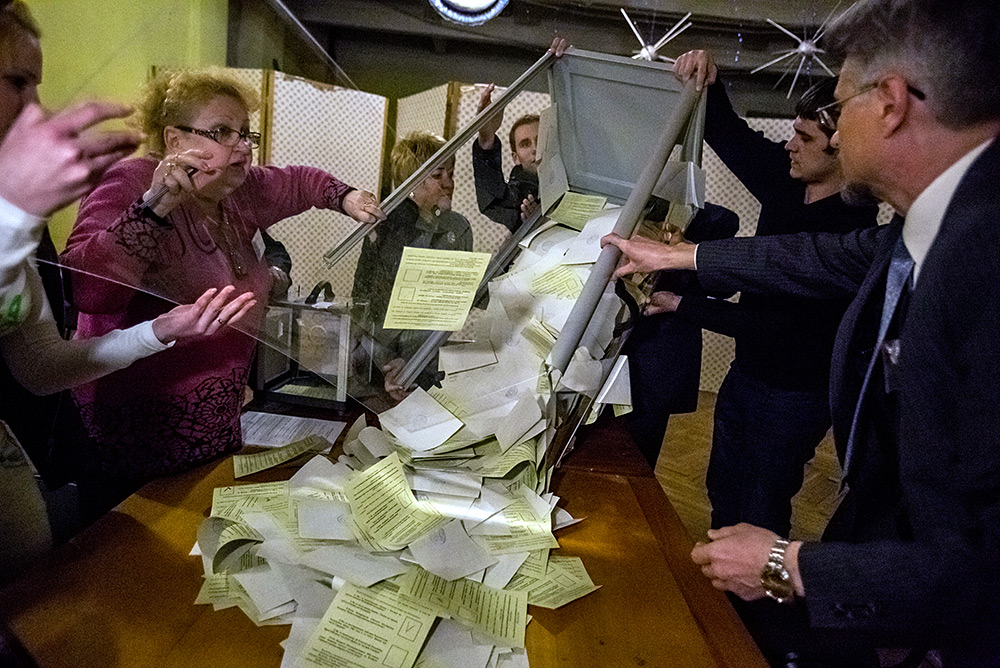

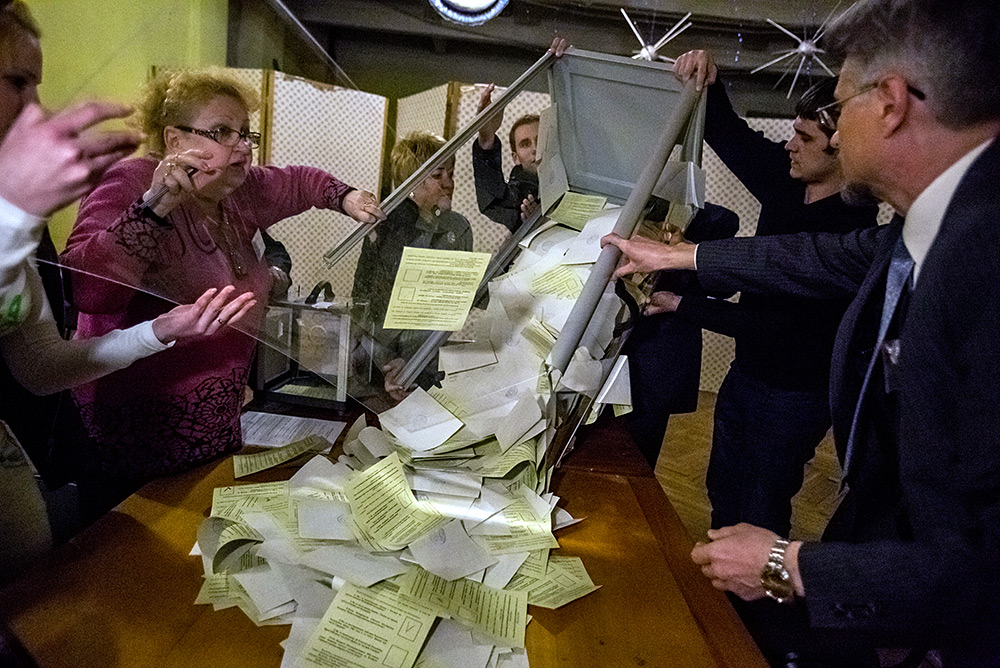

Vote counting during Crimean refendum (RIA/Gazeta.ru)

What's especially interesting is the way he contrasts the Crimean referendum (which he sees as well-executed and perfectly legitimate] and Donetsk referendum (which he sees as not legitimate, though he's sympathetic to the end results). Also, he suggests that Russian political strategies may have have had a more hands-on involvement with the pro-Russian forces in Donetsk Oblast than either side is willing to admit.

I've translated the entire article below

Gazeta.ru: What did you work in Crimea entail? How did it start?

Anonymous Political Strategist: My work came down to developing referendum scenarios and preparing the responses to possible, shall we say, complaints. We took the Kosovo precedent as basis. All the possible complaints about violations of international rights norms we anticipated ahead of time, and the Crimean referendum was conducted on the more lawful foundation that Kosovo's. I honestly believe that international law was formed based on the Anglo-Saxon system and essentially turned into a dumpster of precedents, and its use became the right of the strong.

To be blunt, Russia didn't spend a lot of time digging in that garbage. It didn't delve into the events of 17th-18th centuries, the conditions [of the treaty that originally made Crimea part of the Russian Empire], but took the Kosovo precedent and, as the result, brilliantly organized the Crimea joining process.

That's how Crimea, on the very tight timeline and with complete compliance with the standards of international law, was taken off the board. Undoubtedly, the ability to control the entire territory of the republic and the ability to ensure the electoral process played a role.

Gazeta.ru: Do you mean the "polite armed men?"

APS: Them, and the unconditional support of the local populace. The fact that Ukrainian army refused to take any action definitely played a role, too.

Gazeta.ru: What were the budgets like? How many political strategists that were involved were Russian, and how many were locals?

APS: It may be hard to believe, but I can't say there were political strategies in the proper sense of the word. The Crimean referendum didn't need political strategies. There were highly specialized experts who ensured that all the wording complied with the latest precedents of internal law and ensured that the vote would run smoothly. By the way, the vote itself was much like a calm municipal election in some remote area of one of the Russian regions: clean polling stations, election list. The participation announced by the government was absolutely no different from reality: there wasn't one drawn-in number.

I will also add that there were comical precedents. In Sevastopol and Simferopol, I knew of polling stations where the percentage of people who voted to have Crimea join Russia exceeded the reported number a voters. So, to avoid even a slightest error, orders were given to round off the number of the medium percentage.

Gazeta.ru: How did the Crimean Tatars behave?

APS: Far from all of them are part of Mejilis structure, and definitely not everyone holds an anti-Russian position. Maybe they had some complaints toward the non-Tatar population when it came to dividing up spheres of influence - in the criminal world and in the business area. But, as y current experience shows, many Crimean Tatars quite willingly joined the new government structures. Even structures that may seem strange to us from a Moscow liberal perspective, like "United Russia."

Even among those who followed [former Mejilis chairman Mustafa Dzhemilev], there has been a split. It's no secret that Dzhemilev was essentially removed from power in Mejilis long before the [Crimean Crisis] and was more of a VIP who wanted to be an ayatollah. But, for better or for worse, his role was never well defined, because the situation developed very quickly. And any forces that could be used for anti-Russian purposes were completely unprepared.

Gazeta.ru: Can you say who gave the signal that you need to work in Crimea?

APS: That I can't say. Officially, it was a request from Crimean government. A support group with pretty broad powers was organized. I think that, out of the specialized experts, only about 20 came from the Russian side

Gazeta.ru: Who were they? Strategists, legal experts?

APS: Legal experts, cultural historians. Political strategists in conventional sense weren't really needed, because the level of anticipation and the level of support for Russian government meant we didn't have to drum up turnout, etc.

There was a small group of experts that ensured the vote would run and curated the referendum so that it would run without a single flaw. There were no more than 20 of those curators.

I think that, the complete Russian "landing party" staff that was directly involved in the strategic aspect of the issue was no more than 50 people.

Gazeta.ru: An how much did they pay?

APS: To be honest, I didn't get any reward for this work except my regular rate. I agreed with this work in principle, and, most of importantly, the person who requested it never had serious money. In a situation like this, I didn't even think to ask for more. They consulted us with respect, created work groups. It's interesting to note that, a lot of the ideas suggested by State Duma were rejected in favor of ideas we suggested. Which just goes to show you, once again, how professional our parliament is.

Gazeta.ru: So what exactly didn't you like about Duma's proposals?

APS: They were too multi-tier. To put it bluntly, they originally wanted us to figure out the independence issue first, then vote on joining Russia.

Gazeta.ru: Why didn't you think this would work?

APS: It would work - it's just too complicated. They wanted to make so, they thought, everything would be nice and tidy, so all the questions would need to be decided on the referendum. But that would have led to a delay, by at least a month, and it could have led to consequences no one would need, like what we're currently observing in Donetsk and Luhansk. Anything could've happened. Crimean government could have been declare criminals, there could have been a confrontation that would have gotten Russian troops stationed in Crimea involved...

Gazeta.ru: Crimea saw a wide PR blitz, there were billboards everywhere. Who was responsible for that?

APS: Strictly local experts. Well, maybe with some slight tactical corrections...

For example, we were trying to decide if we should paint the rest of Ukraine with swastikas. At some point, it wasn't allowed, then it was.

Gazeta.ru: So, for the most part, the locals handled the media PR?

APS: Without a doubt. Our experts didn't fully anticipate the Crimean mentality, and that mentality is significantly different from Russian mentality. Crimeans were far more interested in joining Russia at any cost then any issues an average Russian voter cares about, such as healthcare and salaries.

Gazeta.ru: So now, how much harder would it be for Russian strategists to work in Crimea compared to other regions?

APS: Hard to say. It has a very politically active populace. We don't have the kind credibility, or anything that we're used to here.

Right now, we're seeing euphoria in Crimea. Very, in my opinion, right euphoria, which manifests not in waiting for the "golden rain," but in readiness to endure even some losses for the sake of the current status.

Gazeta.ru: Have you been to Donetsk area often?

APS: I can't say I've been there often. More like, I did some research and visited Donetsk region to prepare for the referendum. In my view, it was obvious that the referendum was, first and foremost, a demonstrative gesture, and no one seriously tried to make it correspond to the standards of international law.

At the same time, I'm convinced that the recognition of Crimea as part of Russia will essentially happen by default as time passes. One country after another, one by one.

Gazeta.ru: Who worked on the Donetsk referendum and what did they do?

APS: that work involved a smaller number of specialists. Obviously, the ballots didn't have any protections, the election commissions were appointed by the new government under the timeline that wouldn't be recognized by any law. Everybody understood that perfectly, so the legal experts only did their work up to the point.

The standards for the referendum were much lower. In this instance, political strategists in the proper sense of the word were involved. They were responsible for formulating the ideas of the protest movement. It's a mining region, where joining Russia in on itself wasn't an incentive.

Gazeta.ru: Was it harder to work with miners than with the residents of Crimea?

APS: Strategists created a media strategy first and foremost, set up channels to provide informational support for the rebels. And, in my opinion, they succeeded brilliantly. I don't think that the prominent individuals everybody knows about are really running the show.

Gazeta.ru: What about field commanders?

APS: I wouldn't include them in that. It's a special category of people that cut their teeth probably in Abhazia and Transnistria. Not in 2008 - in 1992. So they are the special people, the "dogs of war."

And there really is a lot of Cossacks. Contrary to popular opinion, the percent of Russian and other [non-Ukrainian] volunteers is significantly lower than half. The Donetsk people's militia is more than two thirds local population and residents of nearby Oblasti.

Gazeta.ru: How much involvement do Moscow and Russian experts have in state-building in Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic?

APS: I can say honestly that, for now, for better or for worse, you can't really talk about building a government in DPR. Right now, we have a situation similar to November-December 1917 [the immidiate aftermath of the revolution that brought Communists to power in Russia], when people who, a lot of times, wind up in their positions by accident, not so much creating a system of government as dealing with the resources they have. It's a war zone. In my opinion, even [Chechnya after the conclusion of the first Russian-Chechen War left it with broad autonomy] shows more signs of a functional government than the east of Ukraine.

That doesn't negate the popular support [for DPR], or the potential the territories have to truly become an independent state. But I don't imagine this is really in the interest of any of the players involved in the Ukrainian crisis.

18.06.2014, 19:07

Как политтехнологи брали Крым

Российский политтехнолог, работавший на референдумах в Крыму и Донбассе, на условиях анонимности рассказал «Газете.Ru»...

http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2014/06/18_a_6075673.shtml

Vote counting during Crimean refendum (RIA/Gazeta.ru)

What's especially interesting is the way he contrasts the Crimean referendum (which he sees as well-executed and perfectly legitimate] and Donetsk referendum (which he sees as not legitimate, though he's sympathetic to the end results). Also, he suggests that Russian political strategies may have have had a more hands-on involvement with the pro-Russian forces in Donetsk Oblast than either side is willing to admit.

I've translated the entire article below

Gazeta.ru: What did you work in Crimea entail? How did it start?

Anonymous Political Strategist: My work came down to developing referendum scenarios and preparing the responses to possible, shall we say, complaints. We took the Kosovo precedent as basis. All the possible complaints about violations of international rights norms we anticipated ahead of time, and the Crimean referendum was conducted on the more lawful foundation that Kosovo's. I honestly believe that international law was formed based on the Anglo-Saxon system and essentially turned into a dumpster of precedents, and its use became the right of the strong.

To be blunt, Russia didn't spend a lot of time digging in that garbage. It didn't delve into the events of 17th-18th centuries, the conditions [of the treaty that originally made Crimea part of the Russian Empire], but took the Kosovo precedent and, as the result, brilliantly organized the Crimea joining process.

That's how Crimea, on the very tight timeline and with complete compliance with the standards of international law, was taken off the board. Undoubtedly, the ability to control the entire territory of the republic and the ability to ensure the electoral process played a role.

Gazeta.ru: Do you mean the "polite armed men?"

APS: Them, and the unconditional support of the local populace. The fact that Ukrainian army refused to take any action definitely played a role, too.

Gazeta.ru: What were the budgets like? How many political strategists that were involved were Russian, and how many were locals?

APS: It may be hard to believe, but I can't say there were political strategies in the proper sense of the word. The Crimean referendum didn't need political strategies. There were highly specialized experts who ensured that all the wording complied with the latest precedents of internal law and ensured that the vote would run smoothly. By the way, the vote itself was much like a calm municipal election in some remote area of one of the Russian regions: clean polling stations, election list. The participation announced by the government was absolutely no different from reality: there wasn't one drawn-in number.

I will also add that there were comical precedents. In Sevastopol and Simferopol, I knew of polling stations where the percentage of people who voted to have Crimea join Russia exceeded the reported number a voters. So, to avoid even a slightest error, orders were given to round off the number of the medium percentage.

Gazeta.ru: How did the Crimean Tatars behave?

APS: Far from all of them are part of Mejilis structure, and definitely not everyone holds an anti-Russian position. Maybe they had some complaints toward the non-Tatar population when it came to dividing up spheres of influence - in the criminal world and in the business area. But, as y current experience shows, many Crimean Tatars quite willingly joined the new government structures. Even structures that may seem strange to us from a Moscow liberal perspective, like "United Russia."

Even among those who followed [former Mejilis chairman Mustafa Dzhemilev], there has been a split. It's no secret that Dzhemilev was essentially removed from power in Mejilis long before the [Crimean Crisis] and was more of a VIP who wanted to be an ayatollah. But, for better or for worse, his role was never well defined, because the situation developed very quickly. And any forces that could be used for anti-Russian purposes were completely unprepared.

Gazeta.ru: Can you say who gave the signal that you need to work in Crimea?

APS: That I can't say. Officially, it was a request from Crimean government. A support group with pretty broad powers was organized. I think that, out of the specialized experts, only about 20 came from the Russian side

Gazeta.ru: Who were they? Strategists, legal experts?

APS: Legal experts, cultural historians. Political strategists in conventional sense weren't really needed, because the level of anticipation and the level of support for Russian government meant we didn't have to drum up turnout, etc.

There was a small group of experts that ensured the vote would run and curated the referendum so that it would run without a single flaw. There were no more than 20 of those curators.

I think that, the complete Russian "landing party" staff that was directly involved in the strategic aspect of the issue was no more than 50 people.

Gazeta.ru: An how much did they pay?

APS: To be honest, I didn't get any reward for this work except my regular rate. I agreed with this work in principle, and, most of importantly, the person who requested it never had serious money. In a situation like this, I didn't even think to ask for more. They consulted us with respect, created work groups. It's interesting to note that, a lot of the ideas suggested by State Duma were rejected in favor of ideas we suggested. Which just goes to show you, once again, how professional our parliament is.

Gazeta.ru: So what exactly didn't you like about Duma's proposals?

APS: They were too multi-tier. To put it bluntly, they originally wanted us to figure out the independence issue first, then vote on joining Russia.

Gazeta.ru: Why didn't you think this would work?

APS: It would work - it's just too complicated. They wanted to make so, they thought, everything would be nice and tidy, so all the questions would need to be decided on the referendum. But that would have led to a delay, by at least a month, and it could have led to consequences no one would need, like what we're currently observing in Donetsk and Luhansk. Anything could've happened. Crimean government could have been declare criminals, there could have been a confrontation that would have gotten Russian troops stationed in Crimea involved...

Gazeta.ru: Crimea saw a wide PR blitz, there were billboards everywhere. Who was responsible for that?

APS: Strictly local experts. Well, maybe with some slight tactical corrections...

For example, we were trying to decide if we should paint the rest of Ukraine with swastikas. At some point, it wasn't allowed, then it was.

Gazeta.ru: So, for the most part, the locals handled the media PR?

APS: Without a doubt. Our experts didn't fully anticipate the Crimean mentality, and that mentality is significantly different from Russian mentality. Crimeans were far more interested in joining Russia at any cost then any issues an average Russian voter cares about, such as healthcare and salaries.

Gazeta.ru: So now, how much harder would it be for Russian strategists to work in Crimea compared to other regions?

APS: Hard to say. It has a very politically active populace. We don't have the kind credibility, or anything that we're used to here.

Right now, we're seeing euphoria in Crimea. Very, in my opinion, right euphoria, which manifests not in waiting for the "golden rain," but in readiness to endure even some losses for the sake of the current status.

Gazeta.ru: Have you been to Donetsk area often?

APS: I can't say I've been there often. More like, I did some research and visited Donetsk region to prepare for the referendum. In my view, it was obvious that the referendum was, first and foremost, a demonstrative gesture, and no one seriously tried to make it correspond to the standards of international law.

At the same time, I'm convinced that the recognition of Crimea as part of Russia will essentially happen by default as time passes. One country after another, one by one.

Gazeta.ru: Who worked on the Donetsk referendum and what did they do?

APS: that work involved a smaller number of specialists. Obviously, the ballots didn't have any protections, the election commissions were appointed by the new government under the timeline that wouldn't be recognized by any law. Everybody understood that perfectly, so the legal experts only did their work up to the point.

The standards for the referendum were much lower. In this instance, political strategists in the proper sense of the word were involved. They were responsible for formulating the ideas of the protest movement. It's a mining region, where joining Russia in on itself wasn't an incentive.

Gazeta.ru: Was it harder to work with miners than with the residents of Crimea?

APS: Strategists created a media strategy first and foremost, set up channels to provide informational support for the rebels. And, in my opinion, they succeeded brilliantly. I don't think that the prominent individuals everybody knows about are really running the show.

Gazeta.ru: What about field commanders?

APS: I wouldn't include them in that. It's a special category of people that cut their teeth probably in Abhazia and Transnistria. Not in 2008 - in 1992. So they are the special people, the "dogs of war."

And there really is a lot of Cossacks. Contrary to popular opinion, the percent of Russian and other [non-Ukrainian] volunteers is significantly lower than half. The Donetsk people's militia is more than two thirds local population and residents of nearby Oblasti.

Gazeta.ru: How much involvement do Moscow and Russian experts have in state-building in Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic?

APS: I can say honestly that, for now, for better or for worse, you can't really talk about building a government in DPR. Right now, we have a situation similar to November-December 1917 [the immidiate aftermath of the revolution that brought Communists to power in Russia], when people who, a lot of times, wind up in their positions by accident, not so much creating a system of government as dealing with the resources they have. It's a war zone. In my opinion, even [Chechnya after the conclusion of the first Russian-Chechen War left it with broad autonomy] shows more signs of a functional government than the east of Ukraine.

That doesn't negate the popular support [for DPR], or the potential the territories have to truly become an independent state. But I don't imagine this is really in the interest of any of the players involved in the Ukrainian crisis.

18.06.2014, 19:07

Как политтехнологи брали Крым

Российский политтехнолог, работавший на референдумах в Крыму и Донбассе, на условиях анонимности рассказал «Газете.Ru»...

http://www.gazeta.ru/politics/2014/06/18_a_6075673.shtml