Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

Originally posted by siochembio at Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans

Sunrise

1927

Director: F.W. Murnau

Starring: George O’Brien, Janet Gaynor, Margaret Livingston

1927 was a turning point for Hollywood. With the commercial success of The Jazz Singer, audiences wanted to hear their films speak to them. At the same time, the silent masters were producing some of the true masterpieces of that era. Sunrise remains one of those masterpieces, making it onto Sight and Sound’s 2002 Critic’s List of the Top Ten Movies of All Time.

The story is, like most silent films, very straightforward. A man from the country (O’Brien) has been cheating on his wife (Gaynor) with a trampy girl from the city (Livingston). The trampy girl, seducing him, asks him to sell his farm and run away with her to the city, drowning his wife in the process. Horrified but unable to escape his girlfriend’s entrancing power, the man sets out to attempt to kill his wife, but guilt stops him at the last second. This is the first half of the film; the second half is a celebration, albeit a bit of an ironic one, of the renewed relationship between husband and wife.

From a very simple premise of infidelity and its repercussions, Sunrise manages unexpected emotional profundity. O’Brien’s performance is stellar. There is certainly some of the typical “silent film mugging,” but for the most part, O’Brien turns in a very honest portrayal of a conflicted man. We understand the attraction to the girlfriend, but also the guilt in seeing his affair through to its bitter end. When he is desperately trying to reconcile with his now terrified wife, we see him begin to understand how much he already has, and what he would be throwing away. It’s an impressive performance. I found myself quite unexpectedly crying in two scenes; the film had managed to sweep me up into its simple story.

Gaynor as his wife is angelic and demur, clearly representing “the correct choice,” what with her halo of blond hair and her sweetly open face. Livingston as the trampy city girlfriend has little to do other than wear black, smoke cigarettes, and generally treat people badly. She’s my least favorite character, and not because she’s separating O’Brien and Gaynor, but because she’s mostly a caricature. Frankly, she looks like Tony Curtis in drag from Some Like It Hot, and I did feel that I was being beat over the head with “Look at how horrible she is! She’s evil!” I could have done with a more subtle villain.

As strong as the emotional journey is, however, the biggest star of Sunrise is Murnau’s camerawork. This is camerawork beyond compare. The sheer inventiveness of Murnau in his shot composition is astounding. Early on, when the husband is contemplating running away with his mistress, the mistress appears as if a spectral ghost, surrounding him, caressing him, whispering to him. Given that there were absolutely zero computer effects in 1927, all these effects had to be done in camera. In this case, it was a double exposure. Later on, when the husband and wife are reconciling, they walk through a city street, only having eyes for each other. Using rear projection, we see all the cars in the street nearly missing the couple, but they don’t notice. Slowly the street fades and turns into a country path. All the while, our couple walks on, oblivious. These are only two examples of Murnau’s original camerawork, all coming to a brilliant head in Sunrise.

Additionally, Murnau was one of the first to use sound as a special effect. There is no spoken dialogue in Sunrise, and refreshingly few intertitles (because really, the story doesn’t need them), but Murnau does employ crowd sounds. Unlike early sound films, however, the sound in Sunrise is natural and unobtrusive. I barely noticed that the crowd was yelling, the horn was honking, or the church bell was ringing, until I remembered halfway through that this was a silent film and wasn’t *supposed* to have sound. I wish more directors had taken a cue from this film and not The Jazz Singer in their early employ of matching recorded sound with images on the screen.

While the special effects are fresh and unexpected, the shot composition itself is just stunning. Clouds, fog, light, and shadows all interplay effectively to produce what can only be described as a gorgeous film. Each shot looks like an expert photograph. The wide shots of the pastoral sets are deliberately reminiscent of Dutch paintings, with farmhouses that look far too idyllic to be real. The city shots of an amusement park seem surreal, they are so full of light and magic.

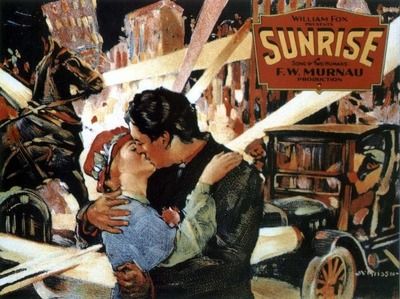

Seriously. How gorgeous. I mean honestly, how amazing is this shot?!?!?!

To be honest, the film does lag in its second half, when our couple is reveling in a night out in The Big City. The emotional core of the film is in its first half; the second half feels a little dragged out. Murnau seems to move from elegant photography and profound emotions to gimmicky hijinks and simple laughs. After going on a bit too long, though, Murnau brings the film back to its initial superiority with a brilliant ending, so we are not left with a sour taste.

How good is Sunrise? Let me put it this way: while gladly rewatching it in order to write this review, I honestly felt sad that sound came to movies. This movie is such an artistic triumph, so brilliant in what it manages to accomplishment, and yet with the commercial success of The Jazz Singer the same year as Sunrise, no studio was interested in producing this kind of film anymore. Early sound films were awkward and clunky. Sunrise is glorious and graceful. Sound, coupled with Murnau’s death in 1931 in a car accident, helped to ensure that Hollywood would not make a film like this… ever again. In that respect, Sunrise marks a glorious, bittersweet end to the willing production of brilliant silent films.

Arbitrary Rating: 9.5/10

Sunrise

1927

Director: F.W. Murnau

Starring: George O’Brien, Janet Gaynor, Margaret Livingston

1927 was a turning point for Hollywood. With the commercial success of The Jazz Singer, audiences wanted to hear their films speak to them. At the same time, the silent masters were producing some of the true masterpieces of that era. Sunrise remains one of those masterpieces, making it onto Sight and Sound’s 2002 Critic’s List of the Top Ten Movies of All Time.

The story is, like most silent films, very straightforward. A man from the country (O’Brien) has been cheating on his wife (Gaynor) with a trampy girl from the city (Livingston). The trampy girl, seducing him, asks him to sell his farm and run away with her to the city, drowning his wife in the process. Horrified but unable to escape his girlfriend’s entrancing power, the man sets out to attempt to kill his wife, but guilt stops him at the last second. This is the first half of the film; the second half is a celebration, albeit a bit of an ironic one, of the renewed relationship between husband and wife.

From a very simple premise of infidelity and its repercussions, Sunrise manages unexpected emotional profundity. O’Brien’s performance is stellar. There is certainly some of the typical “silent film mugging,” but for the most part, O’Brien turns in a very honest portrayal of a conflicted man. We understand the attraction to the girlfriend, but also the guilt in seeing his affair through to its bitter end. When he is desperately trying to reconcile with his now terrified wife, we see him begin to understand how much he already has, and what he would be throwing away. It’s an impressive performance. I found myself quite unexpectedly crying in two scenes; the film had managed to sweep me up into its simple story.

Gaynor as his wife is angelic and demur, clearly representing “the correct choice,” what with her halo of blond hair and her sweetly open face. Livingston as the trampy city girlfriend has little to do other than wear black, smoke cigarettes, and generally treat people badly. She’s my least favorite character, and not because she’s separating O’Brien and Gaynor, but because she’s mostly a caricature. Frankly, she looks like Tony Curtis in drag from Some Like It Hot, and I did feel that I was being beat over the head with “Look at how horrible she is! She’s evil!” I could have done with a more subtle villain.

As strong as the emotional journey is, however, the biggest star of Sunrise is Murnau’s camerawork. This is camerawork beyond compare. The sheer inventiveness of Murnau in his shot composition is astounding. Early on, when the husband is contemplating running away with his mistress, the mistress appears as if a spectral ghost, surrounding him, caressing him, whispering to him. Given that there were absolutely zero computer effects in 1927, all these effects had to be done in camera. In this case, it was a double exposure. Later on, when the husband and wife are reconciling, they walk through a city street, only having eyes for each other. Using rear projection, we see all the cars in the street nearly missing the couple, but they don’t notice. Slowly the street fades and turns into a country path. All the while, our couple walks on, oblivious. These are only two examples of Murnau’s original camerawork, all coming to a brilliant head in Sunrise.

Additionally, Murnau was one of the first to use sound as a special effect. There is no spoken dialogue in Sunrise, and refreshingly few intertitles (because really, the story doesn’t need them), but Murnau does employ crowd sounds. Unlike early sound films, however, the sound in Sunrise is natural and unobtrusive. I barely noticed that the crowd was yelling, the horn was honking, or the church bell was ringing, until I remembered halfway through that this was a silent film and wasn’t *supposed* to have sound. I wish more directors had taken a cue from this film and not The Jazz Singer in their early employ of matching recorded sound with images on the screen.

While the special effects are fresh and unexpected, the shot composition itself is just stunning. Clouds, fog, light, and shadows all interplay effectively to produce what can only be described as a gorgeous film. Each shot looks like an expert photograph. The wide shots of the pastoral sets are deliberately reminiscent of Dutch paintings, with farmhouses that look far too idyllic to be real. The city shots of an amusement park seem surreal, they are so full of light and magic.

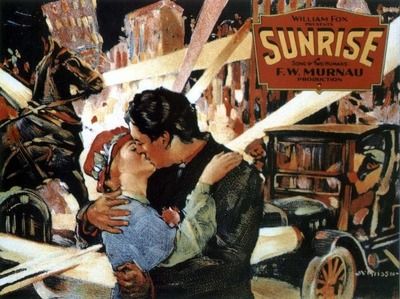

Seriously. How gorgeous. I mean honestly, how amazing is this shot?!?!?!

To be honest, the film does lag in its second half, when our couple is reveling in a night out in The Big City. The emotional core of the film is in its first half; the second half feels a little dragged out. Murnau seems to move from elegant photography and profound emotions to gimmicky hijinks and simple laughs. After going on a bit too long, though, Murnau brings the film back to its initial superiority with a brilliant ending, so we are not left with a sour taste.

How good is Sunrise? Let me put it this way: while gladly rewatching it in order to write this review, I honestly felt sad that sound came to movies. This movie is such an artistic triumph, so brilliant in what it manages to accomplishment, and yet with the commercial success of The Jazz Singer the same year as Sunrise, no studio was interested in producing this kind of film anymore. Early sound films were awkward and clunky. Sunrise is glorious and graceful. Sound, coupled with Murnau’s death in 1931 in a car accident, helped to ensure that Hollywood would not make a film like this… ever again. In that respect, Sunrise marks a glorious, bittersweet end to the willing production of brilliant silent films.

Arbitrary Rating: 9.5/10