The Olmec and collages in New Zealand

New Year's Eve found me freezing in the high desert. During the day I hiked, pretending not to notice the ice on the trails or the biting wind. I'm not a native Californian, I told myself, I'm made of tougher stuff. This doesn't bother me.

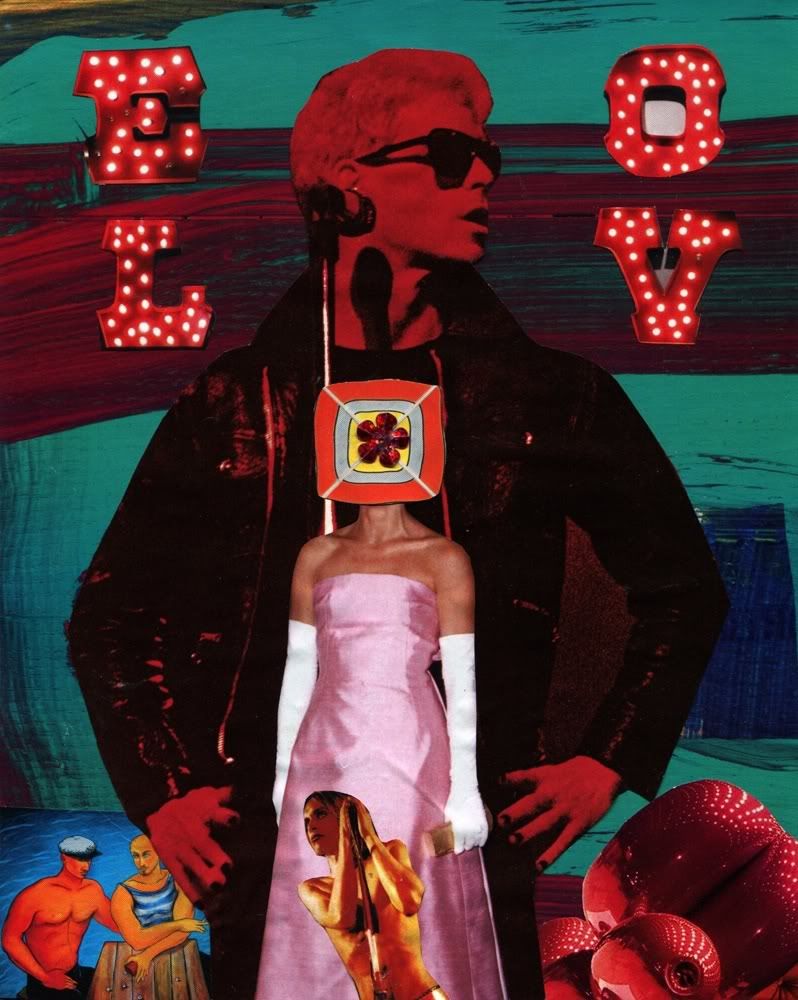

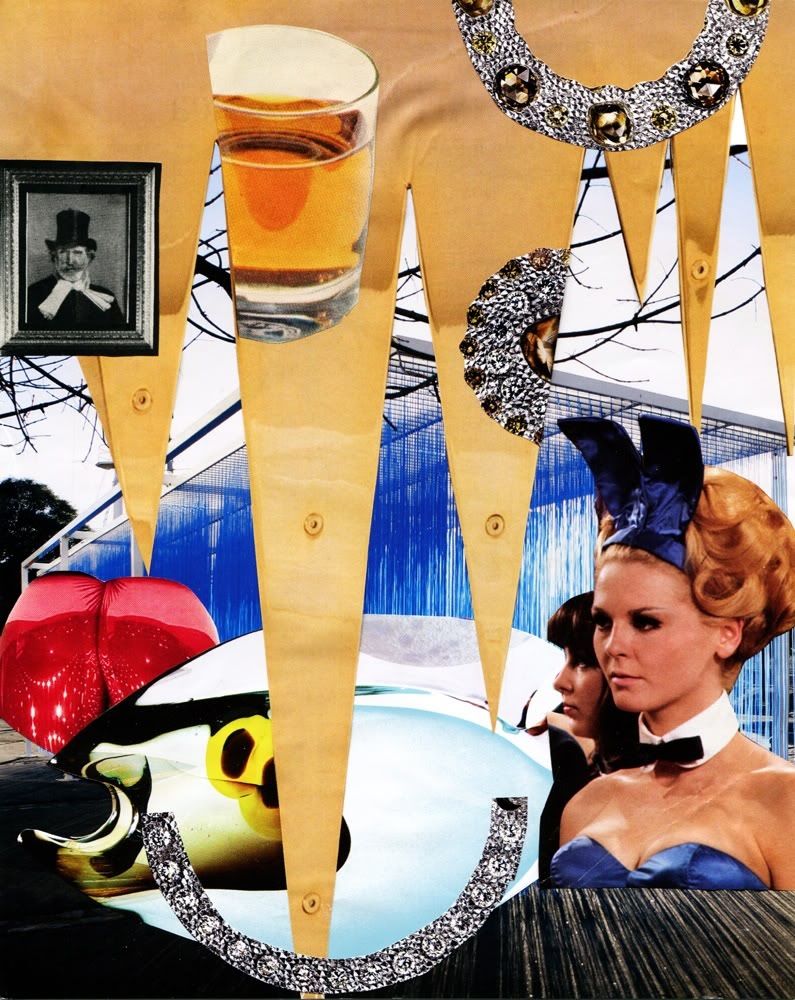

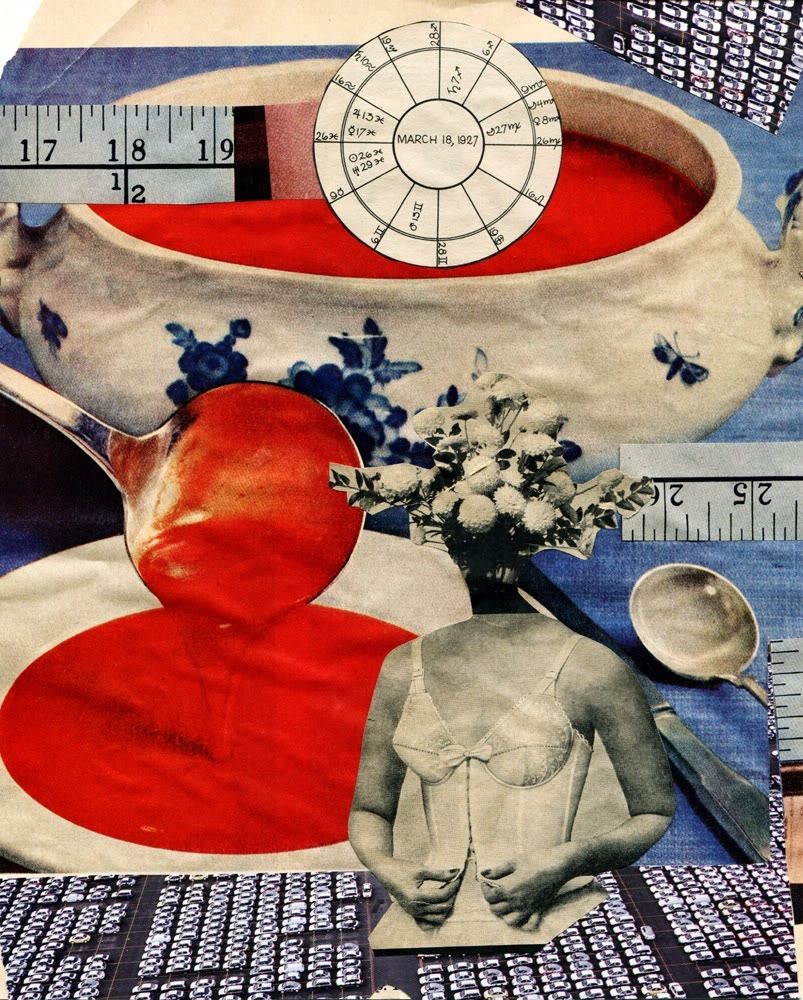

During New Year's Eve and Jan. 1, I made 13 new collages for the exhibit in New Zealand in March. Being in a different environment combined with the holiday and unusual temperatures made this experience frenzied and fun. While I was cutting and pasting in the hotel suite, I listened to a new age radio show out of Palm Springs. People were calling in talking about "chem trails" (sorry folks, I don't believe in that but it's funny as hell to hear people who do). So that's a bit of the ambiance I had going for me.

For the San Francisco Northside magazine's Jan. 2011 issue I wrote about the Olmec. Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico at the de Young museum. This exhibit, for the last few months, has been at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I visited the exhibit and was carried away by the combination of the monolithic heads and the whimsy of the people who created them. I was in awe but at the same time couldn't stop giggling. I knew that when the exhibit moved to San Francisco early this year, I'd have the perfect excuse to write about an era of art I've always admired. Really a once in a lifetime exhibit, I'm glad I saw it. So first the story, then some of the collages.

Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico at the de Young

February 19, 2011-May 8, 2011

By Sharon Anderson

Beginning next month, the de Young will be featuring one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of Olmec culture ever presented to the public. Recognized as one of America’s oldest civilizations, the Olmec were known for their ambitious artworks, most notably colossal heads carved from enormous boulders.

Vessels, figures, ornamentations and ritual masks reveal the story of the Olmec which began around 1400 BC in south central Mexico. Jade, obsidian, magnetite and other materials were manipulated into representations of animals, spirit beings, and humans. They also depicted supernatural beings alongside naturalistic portrayals of objects found in daily life, the symbolism of both the sacred and secular. Stylized animals and spirit entities occupied the natural world simultaneously, reflecting religious meaning and personal history.

The colossal heads are the most enterprising, distinctive and attractive remnants of the Olmec. Now widely considered to be representations of their leaders, these enormous heads were sometimes applied as parts of other monuments. Utilizing primitive tools, the Olmec were able to carve magnificent detailed faces, no two alike, out of basalt, an impossibly hard stone to manipulate. Weighing between 25 and 55 tons, these colossal head sculptures when finished were moved dozens of miles and took hundreds of people months to move to their final destinations. Some heads were variously ravaged, buried and disinterred, displaced to new locations or completely rebuilt. Mutilation had significance beyond common defacement and may have been attributed to invaders. Other historians speculate that the colossal heads were removed from thrones and recycled as freestanding art objects, the defacement having more to do with the symbolic removal of the previous ruler’s power and authority.

The Olmec were innovators of art and invention. The concept of zero as attributed to the Long Count calendar was used by many Mesoamerican cultures. Originally believed to have originated with the Mayans, the idea may have began with the Olmec. Furthermore, the Olmec are thought to be one of the earliest practitioners of human sacrifice. They were also one of the first societies who played ball games. (Some of the colossal heads even depict leaders as ball players.) As the first Mesoamerican civilization, they were the precursors of cultures to follow.

Olmec: Colossal Masterworks of Ancient Mexico represents a vast collection of the era comprised of loans from over 25 museums, some of the objects never before seen in the United States.

Sharon Anderson is an artist and writer in southern California. She can be reached at www.mindtheimage.com