Griboyedov goes political

The St. Petersburg Times

Issue #1543 (4), Friday, January 29, 2010

CULTURE

Secrets of staying on the scene

The director of local club Griboyedov talks about the venue’s experiences with fire inspections and anti-drug raids.

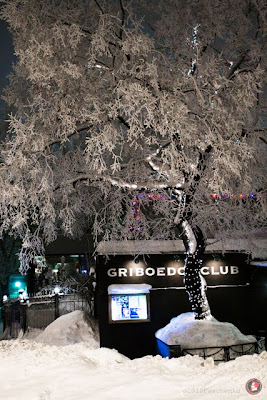

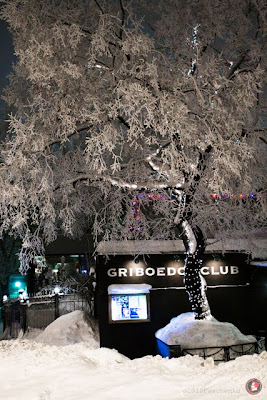

The legendary local club Griboyedov, now in its 14th year,

survived the recent wave of fire safety inspections that followed

the tragic fire in a Perm nightclub that claimed 155 lives late last

year. Photo: Vitaly Feshchenko

By Sergey Chernov

Staff Writer

“Unfettered freedom for nightclubs has ended,” St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko said early last month, ordering a thorough fire safety check for every club or restaurant in the six to eight weeks to follow. Raids and media reports ensued, but the campaign appears to have come to an end, leaving dozens of businesses blacklisted and some closed for the time being. The campaign was a reaction to the Dec. 5 nightclub blaze in Perm, which left 155 dead.

Mikhail Sindalovsky, the director of the city’s oldest surviving music club, Griboyedov, and the drummer with the ska band Dva Samaliota, argues that such campaigns are ineffective, reminiscent of the country’s Soviet past and may be a symptom of totalitarian tendencies in modern Russia.

Partially located in a concrete Cold War bunker, Griboyedov was one of the first establishments to be targeted by fire inspectors. The club was visited by a brigade consisting of a fire inspector, representatives of the Emergency Situations Ministry and Prosecutor’s Office, and two television crews from the locally based Channel Five and the local branch of RTR Television.

“It was an exemplary inspection carried out on the very first day of checks, and if the fire inspector and other [officials] came to inspect the place, then the television people came to shut it down - they held out microphones and kept asking hopefully whether the club was going to be closed,” said Sindalovsky.

The club was found to be safe, but the television reports that ensued cited multiple violations.

“They edited everything and said they didn’t have enough time to record every violation, and that no one could guarantee the safety of people who would come here. It was shown on both channels, put on the web, and all the following reports were made using footage taken here.

“We didn’t know where it would end. There was panic across the country, and some big boss could have seen us on television and said, ‘What is this? Shut it down, kill them all.’ In the same way that Khodorkovsky was thrown in jail.”

Griboyedov was not closed, but another of the city’s music clubs, Glavclub, was. After an inspection, the 2,500-capacity music venue, where bands from The Tiger Lillies to Gogol Bordello and Keane have performed, was blacklisted and ordered by a court to close for 60 days.

As a result, Glavclub had to transfer concerts by international acts such as Reel Big Fish and White Lies to other clubs and stay closed during the Christmas and New Year holidays - the period when clubs make the most profit.

“It was easy for a judge to say, ‘Close it for two months,’” said Sindalovsky. “Why two? Why not one? They’re destroying small businesses, where 30 or 40 to 100 people work. They had paid all the scheduled artists in advance, and now they have to pay the rent and fines, and New Year has gone down the drain.”

Since its inception in 1996, Griboyedov has been visited by the authorities more than once - usually in the form of assault rifle-carrying masked men, who did not identify themselves and created quite a stir in the club. In 1997 The St. Petersburg Times ran a pair of spectacular photographs showing dozens of lightly-dressed club-goers lying face-down in the snow around the bunker during what later become known as an anti-drug raid.

“The OMON or some other special-task force beat people up, stole their possessions and ordered them to lie down in the snow,” said Sindalovsky.

“The same thing still happens now - they come to clubs with assault rifles. What do these morons hope to see, these mask-wearing thugs? They come to a club with a submachine gun; what are they are intending to do - fire it? Or is it simply part of their job, not to be parted from their gun?”

Sindalovsky expressed concern over the wisdom of breaking into a public place bearing firearms. “Imagine, you arrive and there’s a crowd of drunk people. Some drunken idiot could try and get hold of the gun. The shooting will start and they will shoot loads of people. It’s absurd. Who are these big guys who come to a club armed with submachine guns out to get?”

Mikhail Sindalovsky, director of Griboyedov and drummer

in Dva Samaliota. Photo: Vitaly Feshchenko

In December, when the fire prevention campaign was already raging, Matviyenko said that a blacklist of clubs where drugs are sold or used should also be compiled.

“Masked men have been to some places already and searched them,” Sindalovsky said.

State-owned television was prompt to react to the proposal, according to him.

“They zoomed in on a little bag on the floor [in another club], and the reporters said, ‘This club is notorious for drug trafficking, even the locals say so.’ Then they showed some redneck who said, ‘Yes, a lot of drug addicts gather there.’ It’s scary to live in a country like this!”

Sindalovsky argued it was the job of drugs squad officers to locate and catch drug dealers, rather than harassing clubs.

He compared the recent campaigns with the early 1980s anti-truancy campaign launched by then-Soviet leader and former KGB chairman Yury Andropov, during which the police carried out raids on food stores, film theaters and public banyas. Members of the public present were detained and interrogated as to why they were not at work.

“Remember how Andropov carried out raids against people who weren’t at work - they closed sections of the street during the daytime [to interrogate people.] It looks like things are moving toward exactly this,” he said.

“They don’t do their jobs, but they create the opinion among the public that they are fighting drugs in this way. Wherever there are people, there are drug addicts. Cases of drug transportation can be recorded in the metro. Young people study at schools and universities, and some of them use drugs. Take rednecks in the city’s suburb’s - heroin is all the rage among them.

“Why don’t they surround a block, comb it and force everybody down into the snow - it’s likely that they’d find somebody. But it’s not a fight against drugs - it’s nonsense.”

Sindalovsky said the only way of dealing with such attitudes was to inform the public.

“We can’t do anything, but people should know about it at least,” he said.

“They [the authorities] form public opinion. If they say that animals are raped at Uncle Durov’s Corner [a children’s animal theater in Moscow], people will think that that’s exactly what they do there.”

“I came across a volume by [German writer Erich Maria] Remarque on my way back from Germany, containing ‘Arch of Triumph,’ ‘The Night in Lisbon’ [novels set in Nazi Germany]. I read them when I was a child, a long time ago, but when re-reading them now I’ve interpreted them in a slightly different way.

“I don’t mean the books themselves, but about how fascism was taking root, how public opinion was being formed, anti-Jewish sentiment and so on. This is the same kind of thing.”

www.sptimes.ru/index.php?action_id=2&story_id=30712

Issue #1543 (4), Friday, January 29, 2010

CULTURE

Secrets of staying on the scene

The director of local club Griboyedov talks about the venue’s experiences with fire inspections and anti-drug raids.

The legendary local club Griboyedov, now in its 14th year,

survived the recent wave of fire safety inspections that followed

the tragic fire in a Perm nightclub that claimed 155 lives late last

year. Photo: Vitaly Feshchenko

By Sergey Chernov

Staff Writer

“Unfettered freedom for nightclubs has ended,” St. Petersburg Governor Valentina Matviyenko said early last month, ordering a thorough fire safety check for every club or restaurant in the six to eight weeks to follow. Raids and media reports ensued, but the campaign appears to have come to an end, leaving dozens of businesses blacklisted and some closed for the time being. The campaign was a reaction to the Dec. 5 nightclub blaze in Perm, which left 155 dead.

Mikhail Sindalovsky, the director of the city’s oldest surviving music club, Griboyedov, and the drummer with the ska band Dva Samaliota, argues that such campaigns are ineffective, reminiscent of the country’s Soviet past and may be a symptom of totalitarian tendencies in modern Russia.

Partially located in a concrete Cold War bunker, Griboyedov was one of the first establishments to be targeted by fire inspectors. The club was visited by a brigade consisting of a fire inspector, representatives of the Emergency Situations Ministry and Prosecutor’s Office, and two television crews from the locally based Channel Five and the local branch of RTR Television.

“It was an exemplary inspection carried out on the very first day of checks, and if the fire inspector and other [officials] came to inspect the place, then the television people came to shut it down - they held out microphones and kept asking hopefully whether the club was going to be closed,” said Sindalovsky.

The club was found to be safe, but the television reports that ensued cited multiple violations.

“They edited everything and said they didn’t have enough time to record every violation, and that no one could guarantee the safety of people who would come here. It was shown on both channels, put on the web, and all the following reports were made using footage taken here.

“We didn’t know where it would end. There was panic across the country, and some big boss could have seen us on television and said, ‘What is this? Shut it down, kill them all.’ In the same way that Khodorkovsky was thrown in jail.”

Griboyedov was not closed, but another of the city’s music clubs, Glavclub, was. After an inspection, the 2,500-capacity music venue, where bands from The Tiger Lillies to Gogol Bordello and Keane have performed, was blacklisted and ordered by a court to close for 60 days.

As a result, Glavclub had to transfer concerts by international acts such as Reel Big Fish and White Lies to other clubs and stay closed during the Christmas and New Year holidays - the period when clubs make the most profit.

“It was easy for a judge to say, ‘Close it for two months,’” said Sindalovsky. “Why two? Why not one? They’re destroying small businesses, where 30 or 40 to 100 people work. They had paid all the scheduled artists in advance, and now they have to pay the rent and fines, and New Year has gone down the drain.”

Since its inception in 1996, Griboyedov has been visited by the authorities more than once - usually in the form of assault rifle-carrying masked men, who did not identify themselves and created quite a stir in the club. In 1997 The St. Petersburg Times ran a pair of spectacular photographs showing dozens of lightly-dressed club-goers lying face-down in the snow around the bunker during what later become known as an anti-drug raid.

“The OMON or some other special-task force beat people up, stole their possessions and ordered them to lie down in the snow,” said Sindalovsky.

“The same thing still happens now - they come to clubs with assault rifles. What do these morons hope to see, these mask-wearing thugs? They come to a club with a submachine gun; what are they are intending to do - fire it? Or is it simply part of their job, not to be parted from their gun?”

Sindalovsky expressed concern over the wisdom of breaking into a public place bearing firearms. “Imagine, you arrive and there’s a crowd of drunk people. Some drunken idiot could try and get hold of the gun. The shooting will start and they will shoot loads of people. It’s absurd. Who are these big guys who come to a club armed with submachine guns out to get?”

Mikhail Sindalovsky, director of Griboyedov and drummer

in Dva Samaliota. Photo: Vitaly Feshchenko

In December, when the fire prevention campaign was already raging, Matviyenko said that a blacklist of clubs where drugs are sold or used should also be compiled.

“Masked men have been to some places already and searched them,” Sindalovsky said.

State-owned television was prompt to react to the proposal, according to him.

“They zoomed in on a little bag on the floor [in another club], and the reporters said, ‘This club is notorious for drug trafficking, even the locals say so.’ Then they showed some redneck who said, ‘Yes, a lot of drug addicts gather there.’ It’s scary to live in a country like this!”

Sindalovsky argued it was the job of drugs squad officers to locate and catch drug dealers, rather than harassing clubs.

He compared the recent campaigns with the early 1980s anti-truancy campaign launched by then-Soviet leader and former KGB chairman Yury Andropov, during which the police carried out raids on food stores, film theaters and public banyas. Members of the public present were detained and interrogated as to why they were not at work.

“Remember how Andropov carried out raids against people who weren’t at work - they closed sections of the street during the daytime [to interrogate people.] It looks like things are moving toward exactly this,” he said.

“They don’t do their jobs, but they create the opinion among the public that they are fighting drugs in this way. Wherever there are people, there are drug addicts. Cases of drug transportation can be recorded in the metro. Young people study at schools and universities, and some of them use drugs. Take rednecks in the city’s suburb’s - heroin is all the rage among them.

“Why don’t they surround a block, comb it and force everybody down into the snow - it’s likely that they’d find somebody. But it’s not a fight against drugs - it’s nonsense.”

Sindalovsky said the only way of dealing with such attitudes was to inform the public.

“We can’t do anything, but people should know about it at least,” he said.

“They [the authorities] form public opinion. If they say that animals are raped at Uncle Durov’s Corner [a children’s animal theater in Moscow], people will think that that’s exactly what they do there.”

“I came across a volume by [German writer Erich Maria] Remarque on my way back from Germany, containing ‘Arch of Triumph,’ ‘The Night in Lisbon’ [novels set in Nazi Germany]. I read them when I was a child, a long time ago, but when re-reading them now I’ve interpreted them in a slightly different way.

“I don’t mean the books themselves, but about how fascism was taking root, how public opinion was being formed, anti-Jewish sentiment and so on. This is the same kind of thing.”

www.sptimes.ru/index.php?action_id=2&story_id=30712