As Promised: George, The Origins Post

While most biographies tend to date the inofficial beginnings of the Beatles from the day John met Paul (July 6th 1957), with that first encounter being one of those mythical pop history moments like Elvis entering the Sun Studios to make a record for his mother, the first two future Beatles to encounter each other, years before that, and the two who knew each other longest were in fact George and Paul. They went to the same school (Liverpool Institute) and had to take the same bus, which was how they met. (Day of encounter unknown; such is the lot of George.) It went fairly undramatic as a teenage meeting of interests; the only thing that was unusual about it was that Paul was in the grade above George, and broke the unwritten rule of not talking to the younger ones. Those few months age difference were, howeover, significant of how not only the relationship between George and Paul but the relationship between George and everyone else would be shaped. He was the youngest (of four siblings) in his own family already; he would be the youngest in the band, everyone's baby brother, and while that was okay when they were all teenagers, it was anything but okay when they were in their late 20s. At first, though, he and Paul hit it off:

George: By this time I'd met Paul McCartney on the bus, coming back from school. In those days they hadn't brought the buses into the housing development where I lived, so I had to get off the bus and walk for twenty minutes to get home. Paul lived close by where the buses then stopped, on Western Avenue. Just nearby was Halewood, where I used to play in the fields. There were ponds with sticklebacks in. Now there's a sodding great Ford factory there that goes on for acres and acres. So Paul and I used to be on the same bus, in the same school uniform, traveling home from the Liverpool Institute. I discovered that he had a trumpet and he found out that I had a guitar, and we got together. I was about thirteen. He was probably late thirteen or fourteen. He was always nine months older than me. Even now, after all these years, he is still nine months older!

Paul: I knew George from the bus. Before I went to live in Allerton, I lived in Speke. We lived on an estate which they used to call the Trading Estate. (I understand now that they were trying to move industry there to provide jobs, but then we didn't ever consider why it was called a trading estate.) George was a bus stop away. I would get on the bus for school and he would get on the stop after. So, being close to each other in age, we talked - although I tended to talk down to him, because he was a year younger. I know now that that was a failing I had all the way through the Beatle years. If you've known a guy when he's thirteen and you're fourteen, it's hard to think of him as grown-up. I still think of George as a young kid. I still think of Ringo as a very old person because he is two years older. He was the grown-up in the group: when he came to us he had a beard, he had a car and he had a suit. What more proof do you need of grown-upmanship?

While they shared the same school, their attitudes towards it couldn't be more different. Before the double whammy of his mother dying and meeting John Lennon, Paul was a good student ("I ruined Paul's life," John informed Ray Connolly once; "he could have been a teacher, you know"), and fond enough of some of his teachers to rave about one of them, Alan Durband, decades later. ("I had the greatest teacher ever of English literature, called Alan Durband, who was a leading light in the Everyman Theatre, when Willie Russell and everybody were there. He led the fund raising. He'd been taught at Cambridge by F. R. Leavis and used to talk glowingly of him. And he communicated his love of literature to us, which was very difficult because we were Liverpool sixteen-year-olds, 'What d'fuck is dat der?' He'd actually written a ten-minute morning story for the BBC, so I respected this guy. He was nice, a bit authoritarian, but they all had to be in our school because we would have gone had they not held us. We needed holding. He was a good guy. ") George, on the other hand, hated school and all the teachers, simply hated the Institute with a passion. He refused to work ("it's impossible to judge this boy's work because he hasn't done any" says one of his reports), he hated the dress code and deliberately wore as many colourful items as he could get away with under the uniform, transforming himself into the Institute's tiniest teen rebel, and he hated a lot of the other students. Paul's actual younger brother Michael, also at the Liverpool Institute at the time, comments: One of his new friends was George Harrison, who at this time was a bit of a joke at school because he wore his hair so long. And the more the kids laughed and jeered, the longer George let his hair grow. I think in the end he'd have let it grow below his knees if they hadn't all got fed up and left off jeering at him.

What all of this achieved was making Paul feel protective. At lunch, he doled out double helpings from his outpost behind the cafeteria line (one glance at George during pretty much any phase of his life would explain the "feed him now!" impulse), and he dragged him to outings with his other friends. This was not always a rousing success:

There was this guy called Ritter who was in our group at school, and George was in the younger group, and I remember we'd been standing around at playground and I'd tried to introduce George to Ritter, introduce him into my peer group. And being a year younger it was kind of difficult. I said, 'Hey, this is George Harrison. He's a mate of mine. We get on the same bus together.' And we'd been sitting around, and George suddenly head-butted this friend of mine.

When asked for the reason for the headbutt, George replied: "He wasn't worthy of your friendship."

Encounters with George's social circle (read: his family) went more successfully: In Liverpool, Paul would come round my house and we'd play in the living room. Paul knocked me out with his singing especially, although I remember him being a little embarrassed to really sing out, with my whole family walking about. He said he felt funny singing about love and stuff around my dad. (...) When Paul came with us to look at all these guitars, he turned the amp up too high and broke them all. And my mother paid the fee for him. Paul was my mother's favorite Beatle! I was probably her second or third favorite.

They spent their times practicing guitar, once Paul had ditched the trumpet, talking rock'n roll and testing age limits:

Once, George and I had gone to see the film The Blackboard Jungle. It starred Vic Morrow, which was good, but more importantly it had Bill Haley's 'Rock Around The Clock' as its theme tune. The first time I heard that, shivers went up my spine, so we had to go and see the film, just for the title song. I could just about scrape through the sixteen barrier. Even though I was baby-faced, I was just able to bluff it in the grown-up world; but George couldn't. He had all the attitude, but he really was young-looking. I remember going out into his back garden and getting a bit of soil and putting it on his lip as a moustache. It was ridiculous, but I thought, 'He looks the part - we'll get in.' And we did. It was a teenage juvenile-delinquent film, and we were quite disappointed: all acting and talking!

Then there were hitchhiking trips, which George still recalled in great detail forty years later:

One year, Paul and I decided to go hitchhiking. It's something nobody would ever dream of these days. Firstly, you'd probably be mugged before you got through the Mersey Tunnel, and secondly everybody's got cars and is already stuck in a traffic jam. I'd often gone with my family down South to Devon, to Exmouth, so Paul and I decided to go there first.

We didn't have much money. We founded bed-and-breakfast places to stay. We got to one town, and we were walking down a street and it was getting dark. We saw a woman and said, 'Excuse me, do you know if there's somewhere we could stay?' She felt took us to hers - where we beat her, tied her up and robbed her of all her money! Only joking; she let us stay in her boy's room and the next morning cooked us breakfast. She was really nice. I don't know who she was - the Lone Ranger? We continued along the South Coast, towards Exmouth. Along the way we talked to a drunk in a pub who told us his name Oxo Whitney. (He later appears in A Spaniard in the Works. After we'd told John that story, he used the name. So much of John's books is from funny things people told him.) Then we went along to Paignton. We still had hardly any money. We had a little stove, virtually just a tin with a lid. You poured a little meths into the bottom of it and it just about burned, not with any velocity. We had that, and little backpacks, and we'd stop at grocery shops. We'd buy Smedley's spaghetti bolognese or spaghetti Milanese. They were in striped tins: milanese was red stripes, bolognese was dark blue stripes. And Ambrosia creamed rice. We'd open a can, bend back the lid and hold the can over the stove to warm it up. That was what we lived on.

We got to Paignton with no money to spare so we slept on the beach for the night. Somewhere we'd met two Salvation Army girls and they stayed with us and kept us warm for a while. But later it became cold and damp, and I remember being thankful when we decided that was enough and got up in the morning and started walking again. We went up through North Devon and got a ferry boat across to South Wales, because Paul had a relative who was a redcoat in Butlins at Pwllheli, so we thought we'd go there. At Chepstow, we went to the police station and asked to stay in a cell. They said, 'No, bugger off. You can go in the football grandstand, and tell the cocky watchman that we said it was OK.' So we went and slept on a hard board bench. Bloody cold. We left there and hitchhiked on. Going north through Wales we got a ride on a truck. The trucks didn't have a passenger seat in those days so I sat on the engine cover. Paul was sitting on the battery. He had on jeans with zippers on the back pockets and after a while he suddenly leapt up screaming. His zipper had connected the positive and negative on the battery, got red hot, and burnt a big zipper mark across his arse.

When we eventually got to Butlins, we couldn't get in. It was like a German prisoner-of-war camp - Stalag 17 or something. They had barbed-wire fences to keep the holiday-makers in, and us out. So we had to break in. (Ringo started off playing there.) Paul moved from Speke to Forthlin Road in Allerton, which was very close to where John lived on Menlove Avenue. Paul had realized by then that he couldn't sing and play the trumpet at the same time, so he'd decided to get a guitar. We had started playing and were hanging out in school at that time, and when he moved we kept in touch. He lived close enough for me to go on my bike. It would take me twenty minutes or so. I'm amazed when I go back now by car: what seemed like miles then is really only a three-minute car ride.

At which point, of course, John Lennon made his entrance, and everything changed. At first, Paul kept the new relationship with John and being in a band with him and the old relationship with George quite separate. And then he started Operation Get George Into The Band, which wasn't easy but a highly entertaining example of teenage machiavellism, or macca-vellism, as John called it. Paul was eighteen months younger than John, but not shy to offer opinions on how the band should be run practically from the moment he joined. First of all, practice. This dismayed the other Quarrymen who basically had gotten together for a laugh and because John had told them to, and when John told you something, then, unless you were Paul, you did it. Once they got together, things became serious - and fast, says original Quarryman Eric Griffiths. The band was supposed to be a laugh; now they devoted all their attention to it and in a more committed way than any of us really intended. While original drummer Colin Hanton comments: The band quickly became John and Paul. It was always John and Paul, Paul and John. Even when someone didn't turn up to rehearse, John and Paul would be at it, harmonizing, practicing, either at Auntie Mimi's or at Paul's house.

Then there was the look. Behold the Quarrymen at their second gig, on the very July 6th John and Paul met:

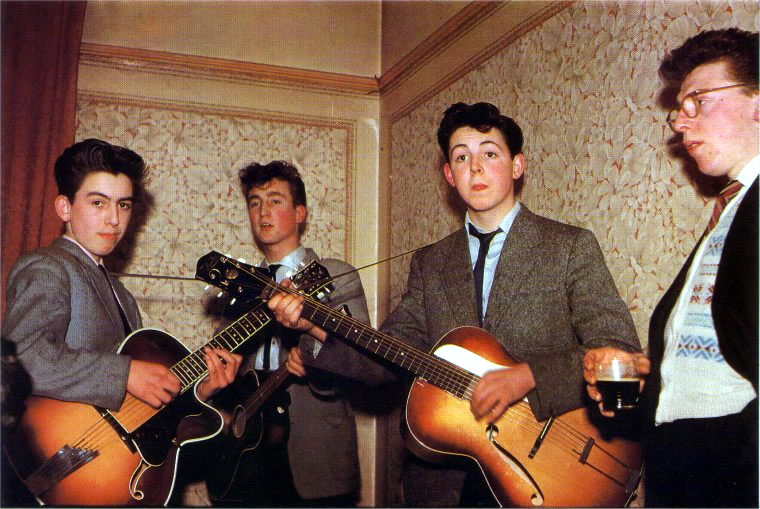

The Quarrymen after Paul had joined:

When it came to the recruiting of new members, however, John balked. George was first introduced to him at a gig the Quarrymen had at Wilson Hall. This resulted in George being struck with instant hero worship he never quite abandoned, but not in George getting hired. John, with his wit, attitude and leader-of-the-pack charisma was the ideal of every teenage rebel, and George was smitten, plus playing in a band was a dream, but John, on the other hand, was less than impressed by George's age. George was just too young, he summed it up later. He looked even younger than Paul, and Paul looked about ten, with his baby face.

Not to be deterred, Paul engineered the next John-and-George encounter, this one in West Oakhill Park, where George at least got around to playing the guitar and demonstrating his unquestionable skills (says Eric Griffiths, until then the third guitarist and not aware his days were soon numbered, The lads were impressed (...) he played the guitar brilliantly), but John still had problems with the age factor, telling Paul that one schoolboy (John at this point had advanced to the adult stage of being an art college student) was enough. Third time was the charm, however, as Paul organized yet another "chance meeting", this one on the empty upper deck of a bus, with no other Quarrymen around. George offered his piece de resistance: Raunchy, played all the way through, an art none of the others had mastered. John capitulated and George was in.

The other Quarrymen, however, were on their way out. Eric Griffiths, now suddenly the fourth and worst guitar player, saw the signs on the horizon and quit. Len Garry contracted tubercular meningitis and quit. John's childhood friend Pete Shotton got a washboard smashed over his head and was out as well. Which left Colin Hanton, and he, you guessed it, quit as well. While this left the remaining three in perpetual need of a drummer, a problem that wouldn't be solved permanently until years later, it also meant John-Paul-George could focus and develop into who they became. That the Liverpool Art College was next door to the Liverpool Institute helped.

Paul and I used to skive out of school and try our best to pretend not to be grammar-school boys. We would hang out with John in the evenings. But in the school days we'd also go out at lunchtime - even thought you weren't allowed out without a special dispensation from the Pope. We'd have to leg it out of school, go around the corner, dispose of as much of our school uniform as possible and then go into the art school. (The building was connected onto the Liverpool Institute.) It was unbelievably relaxed there. Everybody was smoking, or eating egg and chips, while we still had school cabbage and boiled grasshoppers. And there'd be chicks and arty types, everything. It was probably very simple, but from where we came from it looked fun. We could go in there and smoke without anyone giving us a bollocking. John would be friendly to us - but at the same time you could tell that he was always a bit on edge because I looked a bit too young, and so did Paul. I must have only been fifteen then.

I remember that the first time I gained some respect from John was when I fancied a chick in the art college. She was cute in a Brigitte Bardot sense, blonde, with little pigtails. I was playing in Les Stewart's band. (I was in two bands at the same time - there weren't many gigs, one in every blue moon. He lived on Queen's Drive by Muirhead Avenue, so I was hanging out with him as well and learning music in the hope of making a couple of quid.) Anyway, Les had a party at his house and the Brigitte Bardot girl was there, and I pulled her and snogged her. Somehow John found out, and after that he was a bit more impressed with me.

Sidenote: pity the early Beatles girlfriends. Cynthia, John's girlfriend and later wife, had to die her brown hair blonde and dress in black leather skirts to accomodate John's Brigitte Bardon fascination; Dot Rhone, Paul's first steady girlfriend, had to do the same thing. 'Yeah, well, the more they look like Brigitte, the better off we are, mate!' was their unrepentant boyfriends' comment.

John's memories of teenage George from 1980 are a bit more terse: George's relationship with me was one of young follower and older guy. He's three or four years younger than me. It's a love- hate relationship and I think George still bears resentment toward me for being a daddy who left home. He would not agree with this, but that's my feeling about it. (...)(H)e was like a disciple of mine when we started. I was already an art student when Paul and George were still in grammar school. There is a vast difference between being in high school and being in college and I was already in college and already had sexual relationships, already drank and did a lot of things like that. When George was a kid, he used to follow me and my first girlfriend, Cynthia -- who became my wife -- around. We'd come out of art school and he'd be hovering around like those kids at the gate of the Dakota now.

(Sidenote: terse or not, John wasn't completely unjustified with the "resentment toward me for being a daddy who left home" remark. May Pang describes an extraordinary scene where George loses it completely towards John during the lost weekend, screaming things like "I always did what you said but you deserted me" and "Where were you when I needed you!" She said John very calmly sat through this tirade, even when George yelled "I want to see your eyes! I can't see your eyes!" and tore John's glasses off his face and threw them away.)

Cynthia, while also recalling hero-worshipping George following them everywhere ("he would hurriedly catch up to us and ask, 'Where are you two off to? Can I come?"), and who happened to be a year older than John, was a lot less hung up on age and status difference in her memories: When we knew the two boys were coming over at lunchtime, John and I would go across the road for fish and chips. Back in college we'd slip behind the curtain separating the tiny stage from the canteen, which was always packed. A few minutes later Paul and George would arrive. They'd have stripped off their caps and ties and put the collars of their blazers up to look cool as they made their way as casually as they could, through the crowds of students and teachers. Paul always appeared nonchalant, George furtive, as they did their best not to look like the schoolboys they were. When they joined us behind the curtain, we'd lay out the mound of chips and scallops in their paper on the floor and the four of us would dive in. Then the boys began the play.

It can't have escaped George's attention that while he and Paul were both younger than John, Paul had somehow made it to (almost) equal status (possibly because while Paul wasn't entirely free of hero worship at the age of 15, he was hiding it better and went out of his way to be a challenge to John at the same time), and he hadn't. For now, that was okay, not least because he still looked up to Paul as well, and because they could empathize about the new thread on the horizon, one Stuart Sutcliffe, prize student at the art college and lately new friend of John Lennon's whom he persuaded to buy a bass guitar.

Paul: When he came into the band, around Christmas of 1959, we were a little jealous of him; it was something I didn't deal with very well. We were always slightly jealous of John's other friendships. He was the older fellow; it was just the way it was. When Stuart came in, it felt as if he was taking the position away from George and me. We had to take a bit of a back seat. Stuart was John's age, went to art college, was a very good painter and had all the cred that we didn't. We were a bit younger, went to a grammar school and weren't quite serious enough.

(Quoth John: “Paul and George always ganged up on people. Like Stuart. They could get pretty bitchy.”)

Cynthia sums the Stuart situation up with: Stuart wasn't a natural musician and struggled to master the guitar, his fingers callused and bleeding as he practiced for hour after hour. When the boys did a gig he often turned away from the audience so they couldn't see how little he was playing. John knew Stuart was the group's weak link, but he didn't care; he wanted him along. It was the perfectionist Paul who found such an inexperienced guitarist hard to accept, and this led to rows and even fights between him and Stuart. I think Paul was also a bit jealous of Stu; until then he had had most of John's attention.

(There was no "a bit" about it, as Paul later admitted. "He and I used to have a deadly rivalry. I don't know why. He was older and a strong friend of John's. When I look back on it I think we were probably fighting for John's attention.")

As far as George was concerned, he might have been less than thrilled by Stuart himself, but it wasn't that important, because once they were in Hamburg, Stuart fell in love and was less and less around, and far more interesting things happened. Such as losing his virginity. For lo and behold, they were suddenly surrounded by a variety of very accessible women:

George: In the late Fifties in England it wasn't that easy to get it. The girls would all wear brassieres and corsets which seemed like reinforced steel. You could never actually get in anywhere. You'd always be breaking your hand trying to undo everything. I can remember parties at Pete Best's house, or wherever; there'd be these all-night parties and I'd be snogging with some girl and having a hard-on for eight hours till my groin was aching - and not getting any relief. That was how it always was. Those weren't the days. There's that side of it which will always be there, with the different sexes and their desires and all that Testa Rossa-terone bubbling up. And there's the other side of it - the peer-group pressure: 'What, haven't you had it yet?' It becomes, 'Oh, I've got to get it,' and everyone would be lying: 'Yeah, I got it.' - 'Did you get some tit?' - 'I got some tit.' - 'Well, I got some finder pie!' I certainly didn't have a stripper in Hamburg. I know Pete met one. There were young girls in the clubs and we knew a few, but for me it wasn't some big orgy. My first shag was in Hamburg - with Paul and John watching. We were in bunkbeds. They couldn't really see anything because I was under the covers, but after I'd finished they all applauded and cheered. At least they kept quiet whilst I was doing it.

Hamburg was also the first time where George emerged as a favourite for one particular group of fans - the German students liked Stuart best, for the James Dean resemblance, but George was actually tied with John for second place, certainly where the photographers among the students, Astrid Kirchherr and Jürgen Vollmer were concerned. Here are some photos Astrid took of George at age 17:

The doomed Stuart aside, George was the Beatle Astrid took to most, and the one who looked out for her once the band became famous, making sure she got come financial compensation for her photos which were suddenly reprinted everywhere. He was also the one her mother loved best, who was another victim to the "feed him now!" impulse. Visiting the Kirchherrs was also away to relax from the crazy band life:

John: The things we used to do! We used to break the stage down - that was long before The Who came out and broke things; we used to leave guitars playing on stage with no people there. We'd be so drunk, we used to smash the machinery. And this was all though frustration, not as an intellectual thought: 'We will break the stage, we will wear a toilet seat round our neck, we will go on naked.' We just did it, through being drunk.

(...) We were just kids. George threw some food at me once on stage. The row was over something stupid. I said I would smash his face in for him. We had a shouting match, but that was all; I never did anything. And I once threw a plate of food over George. That's the only violence we ever had between us.

George: John threw all kinds of stuff over everybody, over the years. I can't remember that happening, but if he said it it must have happened. There were times when he did throw stuff. He got pretty wired. The down, adverse effects of drink and Preludins, where you'd be up for days, were that you'd start hallucinating and getting a bit weird. John would sometimes get on the edge. He'd come in in the early hours of the morning and be ranting, and I'd be lying there pretending to be asleep, hoping he wouldn't notice me. One time Paul had a chick in bed and John came in and got a pair of scissors and cut all her clothes into pieces and then wrecked the wardrobe. He got like that occasionally; it was because of the pills and being up too long.

(Sidenote: somehwere in Germany there must be a woman around 70 who was traumatized mid-sex with Paul McCartney by John Lennon and his scissors, and she never told her story to a single tabloid. How's that for discretion?)

Then the time in Hamburg came to an abrupt end when a tip by a vengeful club owner informed the police George was still underage and not allowed to visit a club on the Reeperbahn after 10 pm, let alone work in one. He was unceremoniously deported:

I had to go back home and that was right at a critical time, because we'd just been offered a job at another club down the road, the Top Ten, which was a much cooler club. In our hour off from the Kaiserkeller we'd go there to watch Sheridan or whoever was playing. The manager had poached us from Bruno Koschmider and we'd already played a couple of times there. There was a really good atmosphere in that club. It had a great sound-system, it looked much better and they paid a bit more money. Here we were, leaving the Kaiserkeller to go to the Top Ten, really eager to go there - and right at that point they came and kicked me out of town. So I was moving out to go home and they were moving out to go to this great club.

Astrid, and probably Stuart, dropped me at Hamburg station. It was a long journey on my own on the train to the Hook of Holland. From there I got the day boat. It seemed to take ages and I didn't have much money - I was praying I'd have enough. I had to get from Harwich to Liverpool Street Station and then a taxi across to Euston. From there I got a train to Liverpool. I can remember it now: I had an amplifier that I'd bought in Hamburg and a crappy suitcase and things in boxes, paper bags with my clothes in, and a guitar. I had too many things to carry and was standing in the corridor of the train with my belongings around me, and lots of soldiers on the train, drinking. I finally got to Liverpool and took a taxi home - I just about made it. I got home penniless. It took everything I had to get me back.

I had returned to England, on my own and all forlorn, but as it turned out, Paul and Pete were booted out at the same time and were already back ahead of me. It seems Bruno didn't want The Beatles to leave his club and, as there had been an accidental fire, he had got the police in. Bruno said that they were burning his cinema down and they took Pete and Paul and put them in the police station on the Reeperbahn for a few hours and then flew them back to England. Deported them. Then John came back a few days after them, because there was no point in him staying and Stuart stayed because he'd decided to get together with Astrid. It was great, a reprieve, otherwise I had visions of our band staying on there with me stuck in Liverpool, and that would be it.

And thus I'll leave young George, forelorn yet hopefully awaiting reunion with his bandmates. And not a virgin anymore.

This entry was originally posted at http://selenak.dreamwidth.org/620394.html. Comment there or here, as you wish.