"Race Music" - An Excerpt from POWERCHORDS

Don’t they know Rock’s just for whites?

Don’t they know the rules?

- Body Count, “There Goes the Neighborhood”

Racism forms the bedrock of music as we know it now. The loathsome “triangle” slave trade forced people from West and Central Africa together with European colonists (some of whom owned slaves, many of whom did not), along with the Scottish, Irish and English convicts shipped over to work England’s North American colonies. Mingled with the various musical traditions of the Native Americans who were also enslaved - and eventually exterminated - throughout the Americas, these cultural traditions formed the roots of Jazz, American Folk, Gospel, Mariachi and, of course, the Blues… as well as the many forms of music that flowed from them (Rock, Country, Reggae, Salsa, Hip-Hop and so forth). These American styles, in turn, influenced European Classical composers like Copeland, Joplin and Bernstein, incidentally shaping the operatic arts into Broadway musicals, Bollywood, and the dreaded “concept album.”

Race-based “colonialism” in Asia during the 1800s added interplays between the European Classical school and various musical traditions of Chinese, Indian and Japanese music - a combination that influenced artists as disparate as Tan Dun, Yoko Ono and The Beatles. And although Middle Eastern musicology has inspired (and often shaped) European music since ancient Egypt, infusions of “orientalism” during the 1800s and 1900s brought strong Turkish, Persian and Arabian flavors to the European and American styles. The results can be heard in nightclubs, yoga studios and concert halls worldwide.

“Degenerate Influences”

This racism cuts deeper than skin color. Until the 20th century (and, sadly, in some regions even now), the idea that humanity is divided into distinct racial “species” was considered a scientific, theological and governmental law. This idea included divisions not only of skin color, but of nationality and even social class. The Scots and Irish, for example, were considered as “subhuman” by their English masters as were Africans or Native Americans… sometimes more so. Even lower-class Europeans were regarded as genetically inferior to the refined aristocracy, an idea embodied by “well-bred gentleman” and “inbred redneck” stereotypes common throughout most cultures. Such racism isn’t just a white man’s game, either. Until very recently, the “high” musical traditions of the aristocracy and the “low” traditions of their social inferiors were kept rigidly separated, throughout almost every global culture, in order to save the “purity” of the upper classes from contamination by the “mongrels” underneath.

(This idea’s still alive and well, as any Hip-Hop fan can attest; the pages of David Tame’s book The Secret Power of Music, published in 1984, are saturated with it. “A sign of the future, then?” Tame writes while deploring the effects of African elements on the European Classical tradition: “Western music improved and evolved in our time from Bach, Beethoven and Wagner - to the jungle beat!” Tame actually predicts the destruction of all human civilization thanks to the influence of Jazz and Blues. The irony of his reverence for Wagner, whose music literally did inspire the Holocaust, eludes Tame… and to this day, he’s not alone in that regard.)

The music industry, too, was founded largely upon racial discrimination - not only against African-Americans but against the Celtic and Germanic “hicks” of Appalachia, too. Originally created to preserve and disseminate European symphonies, early recording technology was too bulky and expensive to be “wasted” on lower-caste musicians. Eventually, though, a combination of anthropological research into Black and Appalachian America, together with appeals to the vast so-called Negro audience, led to pioneering Folk and Blues recordings. Even then, however, most record albums (and nearly all radio airtime) were reserved for upper-class white artists, frequently releasing watered-down versions of music originated by Black and Appalachian musicians. Giving rise to Big Band and the Jazz Crooner styles, these recordings inspired anyone who could afford a radio, a record player, or a visit to the movies. The barriers began to tremble.

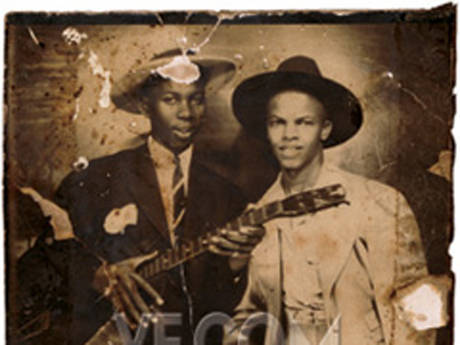

Meanwhile, canny broadcasters, artists and producers founded record labels and radio stations specializing in music for Black and working-class white audiences. Segregated from the mainstream not only by custom but often by law, this “race music” flourished in poor, bohemian and oppressed communities throughout Europe, the Americas and parts of Asia. It jazzed film soundtracks, rocked speakeasies, and jitterbugged through airwaves and alleyways between the two World Wars. As authentic Blues, Folk, Country, Jazz and other forms reached wider audiences, those audiences - and their musicians - responded. In the early 1950s, the walls between “race music” and the “respectable” varieties began shaking, then breaking, then exploding. Despite often-violent crackdowns, the 1960s featured a revolution of ethnic musicality unprecedented in history and unseen, really, ever since.

Cultural Comfort Zones

After Vietnam, however, the music industry and its audience began regrouping along class and racial lines. Rock - ignited and invigorated by Black artists like Bo Diddly and Jimi Hendrix - became “white-boy music”… so much so that artists like Living Color, Fishbone and Body Count met resistance from both sides of the black-white divide. Radio stations, promoters and record merchants dove behind labels like Soul, Pop and Country-Western, to the extent that a visitor to a 1980s record store might find only two or three Black artists outside the sections devoted to Jazz and Soul/ Rap/ R&B… and few, if any, European, Asian or Latin-American artists in those.

Once again, the disreputable underclasses featured more ethnic integration than the cultural mainstreams; Punk and Reggae shared more space in 1970s London dives than Soul and Rock shared in 1970s Detroit living rooms. Hip-Hop shook its fist from New York streets, but was utterly invisible (along with Black musicians other than Michael Jackson) on TV until the late 1980s. In yet another cultural irony, the primary mixing ground of racial musicianship throughout the 1970s occurred in space maintained by the despised and often illegal gay subculture: the discotheques. Fired by Dionysian blends of sex, drugs, dance and masquerade, Disco culture hit the mainstream in the mid-70s, blasting through the bland backwash of post-‘60s popular music. Within the next two decades, Punk, Techno and Hip-Hop (all of which also rose from oppressed ethnicities) would have similar effects. Even so, most popular music between the early ‘70s and early ‘90s was again segregated by class and color. To an extent, it still is.

Musically, cultural influences are more diverse now than ever. Artists routinely spin global elements into all forms of art and image. That said, the racist legacy lingers in the business of buying, selling and promoting musicianship; even as the old ethnic barriers fall, the music we know and love is shaped by what went before. Despite labels like Def Jam, festivals like Lollapalooza, artists like Gorillaz and subgenres like Death Metal, the music industry in 2010 remains stubbornly shaped by racial divisions. While Hip-Hop has essentially replaced Rock as the dominant force in popular culture - in large part because it resonates with oppressed people everywhere - it’s still rare to see Black kids in Goth gear, or Asian agents scoping out bars bands on a Cheyenne reservation. Mixed-race bands are literal minorities, and artists beyond the American black-white polarity are virtually unheard beyond the “Latin,” New Age, Techno and World Music ghettos. Euro-ethnic artists still record faux-Soul tracks to great success, and the most successful artist in South America still learned English, dyed her hair and dumbed her style down before breaking big on the global stage… and the fact that Your Humble White-Boy Author really enjoys Joss Stone and Shakira doesn’t mitigate my dismay with that situation, either.

If nothing else (he says, dumping authorial objectivity in the corner where it probably belongs), it kinda deepens that disappointment with myself. Although my formative musical years included Doo-Wop and Blues (thank you, Dad!), Soul and bits of Ska, it took me decades to hear Rap as anything more than pissed-off assholes shouting obscenities over other people's drum tracks - and I’m ashamed it took so long. While it annoyed me that the record chain I worked for during 1989 had ghettoized all Black artists save Hendrix, Michael Jackson and Tracy Chapman under “Jazz” and “R&B,” I hadn’t realized how deeply I’d accepted that false division myself. Nor am I alone there; working in the Barnes & Noble music department for six years in three locations, I saw most people, regardless of ethnicity, refusing to look or listen beyond their cultural comfort zones.

This section, in part, is an admission of my own ethnic myopia, an apology for it, and a revelation to you, the reader, that such racism pervades the form and history of music as we know it now. Understanding this element, we can see it, learn from it, transcend it, and ultimately transform it into something better than what we’ve received so far… which, when you consider how potent music has been throughout the last century, is pretty damned miraculous… without or without elves.

-----------------------------------------

Article excerpted from POWERCHORDS - Music, Magic & Urban Fantasy. Images remain the property of their respective creators. Text copyright(c) 2010 SatyrPhil Brucato & Silver Satyr Studios. Permission granted to repost this article, with attribution given. Permission for all other forms of publication explicitly denied. All rights retained by Author. Don't steal other people's stuff - it's obnoxious! Thanks.