The Da Shan Dynasty part 5: The Special Guest

Although I am by nature a lazy thinker, I do try and bear in mind when thinking about things like the events of 1989 that oversimplistic analysis will lead me straight to the wrong conclusions. Furthermore, comparisons, says the old adage, are odious, especially, as the Chinese Government is always so keen to point out, when they concern China and the West. I am also no expert on recent Chinese history. There are almost certainly people reading this who know a thousand times more about these things than I do, and I would be grateful if they would step in and correct me if I get too carried away.

China and Eastern Europe are a long way away from one another, and the prevailing circumstances in 1989 were different in all sorts of ways. This is why the Chinese Communist Party survived not just the turn of the decade but also into the new millennium, while the Communist Parties of Eastern Europe simply disappeared. Here I want to concentrate on those different circumstances:

1. The economy. Although China was still in the process of recovering from complete devastation, the economy was growing, and on the whole people were enjoying an improving standard of living. There were problems with inflation, huge disparities of wealth and low wages throughout the country, but the country was not on its last legs like the countries of the soon-to-be-former Eastern Bloc.

2. The political situation. I think generally people were happy that their leaders were heading in the right direction, albeit perhaps too slowly. People were enjoying more freedom than they had experienced within living memory, given that most of the adult population had experienced at least part of the Cultural Revolution.

As far as I can see, the demonstrations in 1987 and 1989 expressed a growing political confidence which derived from ten years of liberalisation. People were making demands of the system - greater freedom of speech, an end to corruption, better and more responsible government - but I don't think they wanted to see an end to Party rule. The demonstrations were quite different from the ones we don't see reported in the state media today, which tend to be localised reactions to individual cases of corruption and injustice. This is one of the things that I'm completely happy to admit being mistaken about.

3. Lack of political leadership. Jung Chang refers in her new book to the Cultural Revolution as the 'Great Purge'. Successive generations of potential dissidents had been massacred, driven to suicide, locked away or forced to leave the country. The person who was perhaps China's best hope of a Václav Havel, Wei Jingsheng, was part of the Beijing Wall group of dissidents and was locked up in 1979 for 14 years. There was, therefore, no previous generation of rebels from whose mistakes the protestors could learn.

Students groups obviously played a role in the building of the demonstrations, but they certainly didn't constitute a 'government-in-waiting'.

The leader who most resembled a Chinese Gorbachev, Hu Yaobang, had been sacked by Deng Xiaoping in 1987 for being too liberal, and it was his death two years later that was the initial pretext for the build-up of protestors around the square in April 1989. They were of course other reformists high up in the party, but it seems that around this time they did not have the upper hand.

4. Lack of foreign media influence. The state media was very tightly controlled, and the only alternative, the broadcasts of the BBC and other media news organisations, could only be listened to by the tiny proportion of the population who could understand English.

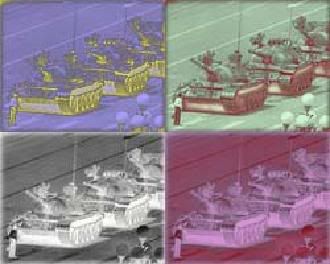

These were I think some of the most important differences between the situation in China and in the countries of Eastern Europe in 1989. However, this set of circumstances did not have to inevitably lead to the events that followed - the Massacre and the unleashing of political repression. It might be interesting, just now we're here, to speculate about how, given the circumstances above, things might have turned out differently.

Let's just say that, instead of giving the order to physically clear the square at all costs, the leadership had dithered. Maybe nobody wanted to be responsible for taking such a momentous decision. Or maybe, having received the order to attack, the army chiefs had not felt comfortable with the situation, and refused to do so. Or even if, and this is probably stretching it quite a bit, the soldiers of the 27th Army had refused to open fire. The leadership would have faced a crisis, and maybe, sensing that the Government didn't know what to do, the protests would have kept on growing throughout the country. The eyes of the world would have been focussed on Beijing, through the lenses of the new global 24-hour news gathering organisations. Protests were growing throughout Eastern Europe too; could the line of dominos reach China? Maybe heads would have rolled in Beijing, people resigning and being forced to resign, nobody sure what to do in this unique situation, nobody wanting to be remembered as the leader who stood in Beijing 40 years on and told the growing mass of Chinese people to sit down again. Maybe the drama would have unfolded with a gradual hollowing-out of the centre of power as the leadership tossed the poisoned chalice of leadership back and forth.

In many accounts written by people who defend the use of force to clear the square, one factor is all important. With the approach of that 40 year anniversary, a special guest was expected, and the Chinese could not be seen to lose face in such a dramatic fashion. Mikhail Gorbachev had recently stood with the East German leadership at their 40th anniversary parade. He had told them what they least wanted to hear, that 'die Wende' had passed:

Mikhail Gorbachev stood next to Honecker, but he looked uncomfortable among the much older Germans. He had come to tell them it was over, to convince the leadership to adopt his reformist policies. He had spoken openly about the danger of not ‘responding to reality’. He pointedly told the Politbüro that ‘life punishes those who come too late’. Honecker and Mielke ignored him, just as they ignored the crowds when they chanted, ‘Gorby, help us! Gorby, help us!’

If Gorbachev had arrived in Beijing in the midst of this crisis armed with the same advice, how would he have been received? Perhaps the hardliners like Li Peng would have chosen to ignore him, in the same way that Honecker and Mielke chose to take no notice. But maybe at this stage he wouldn't have been dealing with the hardliners. Would there have been anyone among the leadership of the Communist Party who might have been prepared to listen, who might have seen a potential way out of the deadlock? Another Chinese Gorbachev, if you like?