The Enemy Within

George Orwell, in his book ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’, describes in detail the physical hell that Britain’s coal miners had to endure in return for a living wage:

Most of the things one imagines in hell are in there - heat, noise, confusion, darkness, foul air, and, above all, unbearably cramped space. Everything except the fire, for there is no fire down there except the feeble beams of Davy lamps and electric torches which scarcely penetrate the clouds of coal dust.

The miner's job would be as much beyond my power as it would be to perform on a flying trapeze or to win the Grand National ... by no conceivable amount of effort or training could I become a coal-miner, the work would kill me in a few weeks.

This strength that the miners exhibited, invisibly, underground had to have some counterpart on the surface. And so the National Union of Mineworkers fought on their behalf to defend their safety and their livelihoods.

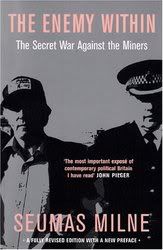

Sixty years later Guardian journalist Seamus Milne, in his book ‘The Enemy Within: Thatcher's Secret War Against the Miners’, detailed how the vendetta that Margaret Thatcher’s 1980s Conservative government held against the NUM. Margaret Thatcher regarded the miners, with their collective recourse to industrial action to defend their jobs, their wages and the safety regulations that kept them alive, as ‘the enemy within’. The Chancellor Nigel Lawson felt that the Government had a duty to confront and destroy the miner’s industrial power akin to facing ‘the threat of Hitler in the late 1930s’. The bitter strike which resulted lasted for almost a year and was lost, narrowly, by the miners.

The consequences for the Labour movement were, just as the Tories had calculated, catastrophic. Membership of trade unions has almost halved since Thatcher and Co. began their all out assault on trade union power in 1979, and had already diminished considerably by 1992, when the Government announced that it was to close a third of Britain’s coal pits, with the loss of 31,000 jobs. There were huge protests against the closures but the NUM itself had already lost a great deal of members and a lot of the support which had sustained it through the strike eight years earlier. The Labour Party, which was in the process of concluding that if it was ever to regain power it would have to abandon most of its founding principles, offered no support whatsoever and the battle was lost.

Now what pits survive in Britain are in private hands, employing a tiny amount of people in very unsafe conditions. The communities that came into being because of the mines are now some of Europe’s poorest towns, suffering from high levels of long-term unemployment and heroin addiction. Not that the world has no need of coal, or that its production is not profitable; the regular news reports from China about tragic accidents show us where and how it is obtained, and at what price.

There is a hidden story of the miner’s strike of 1984-5, and particularly of what happened six years later. On 5 March 1990 the Daily Mirror published a front-page attack against the leaders of the miners’ union, backed by an investigative programme on TV the same night, claiming that not only had money been received during the year long dispute from the Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi, at the time reviled as a sponsor of terrorism, but that the cash had subsequently been used not to ease the hardship of strikers but to pay off the mortgages of officials. The leaders of the union, in particular Arthur Scargill, were vilified and disgraced.

Within a short space of time, after vigorous investigation and campaigning by the few groups on the left who stood by Scargill, the Mirror’s story was revealed to be a complete fabrication. Neither of the officials in question even had mortgages. A subsequent inquiry into the Union’s affairs cleared them of any wrongdoing whatsoever.

Seamus Milne’s book set out to discover who was behind the fake story, and came up with some astonishing revelations if its own.

The union official who instigated the fund-raising trip to Libya was the Chief Executive, Roger Windsor. He had his photograph taken with Gaddafi; its publication in the newspapers, at a time when, as Thatcher later admitted, it looked as though the miners might actually win the strike, can’t have done wonders for their cause.

At the time he was the highest non-elected official at the NUM. He was ideally placed, then, to provide the Daily Mirror with evidence against Scargill six years later; for which the newspaper paid him the sum of £80,000.

Following evidence provided by the Labour MP Tam Dalyell, Seamus Milne looked into the links between Roger Windsor and the British secret services and found that the man behind the allegations, the man who had tried to smear and discredit Scargill, the NUM and by extension the entire Labour movement, had in fact been working all along for MI5.

It is quite possible that if had not been for the damaging impact of the Mirror's allegations, the Tories would not have been able to push through the mass pit closures they would announce two years later. A certain amount of mud stuck, and the prominence that the newspapers gave to their retractions of the story did not, of course, match in any sense the publicity that the lying revelations had received. It would be twelve years before the Mirror’s editor would make a public apology for his actions.

No-one else involved in the campaign seems to have done so. One of the main promoters of the story, the then Mirror owner Robert Maxwell, would kill himself in 1991, shortly before it was revealed that he himself had been funding his business adventures by stealing from the pension fund of the newspaper. In the course of a lifetime of gargantuan self-promotion and deceit, he himself had had his own fair share of dealings with the secret services, and was described by the Mirror’s then editor as ‘the world's most intrusive proprietor’.

The role of the Labour Party in the strike was pretty treacherous; they were already coming to the conclusion that in order to regain power they would have to try to abandon most of their core beliefs, and adopt an agenda more akin to the philosophy of their political enemies. The Miners’ Strike would propel them further along the path that lead to Blairism and New Labour.

I first read Seamus Milne’s book when it was published in 1995, since which time a question has been slowly forming in my consciousness; it is only recently that I have become aware of what its implications might, erm, imply: if the secret services in the 1980s would go to such lengths as to plant people among the leadership of the union branch of the Labour movement, what moves would they be prepared to take to divest the political wing of the Labour movement of its popular force and ingrained ideology - that is to say, the Labour Party?