Some Thoughts On William S. Burroughs

The first Burroughs novel I read was Interzone, At the time, I was still not familiar with Kerouac and the rest of the beats and, most importantly, Henry Miller (who kind "put American Literature together" for me, if you follow). I was about sixteen years old, had only just begun to sense the movements beneath the surface of some works which simply weren't present in other works. Not to sound cryptic, I'm saying I was only just then learning to distinguish between prose and writing. . . Get me? Anyway, I was comically under-equipped to approach these works.

Interzone was the first. The copy I got was prepared by Penguin. I had to special-order it from the closest bookstore. . . a place twenty-five minutes away that pandered to middle-aged housewives with no taste in literature. Romances. It was called The Little Professor Book Store. The next tier of clientele down would have been Stephen King and Dean Koontz fans (a crowd just as lowly, only smaller). . . That's where I'd been, more or less. Interzone may very well have been the first book I ever ordered.

That copy of Interzone came piggy-backed with a poem WSB had written. It was called "WORD" and I picked up on the religious reference before I even started reading it. I'm jumping the gun a little bit, here. I knew WORD was there, but I didn't get to it until after I'd finished Interzone. Interzone was a collection of short stories and sketches all centered around Tangier gone to Hell. Every law and rule and sense of order was corrupted and some people adapted and some didn't and fuck those that try to put a stop to it. You like shit like that a lot more when you're that age, I think.

The stories were weird. The weirdest I'd ever read. I didn't touch Stephen King *or* William Gibson for years and years, after reading Interzone. I remember being struck by the amount of attention he paid to the characters' surroundings. Burroughs wrote some excellent descriptive passages, throughout his career. His landscapes and sets were always good. These little stories were obviously stitched together, but taken one by one, they made enough sense on their own terms and were--more or less--straightahead narratives.

Much unlike WORD. If I remember the page layout correctly, it was a series of couplets running several dozen pages. The lines themselves didn't seem to hold much by way of coherency. Sets of lines didn't offer much, either. In fact, you could go on for pages and pages and there wasn't much there.

Sure. . . there are BIG IDEAS running through it. Sex, Money. Food. Excrement. Death. But they aren't developed. . . they don't go anywhere. . . you don't even get to see enough of one, you just catch a glimpse of a Death's Head in a cradle and then it's gone.

It's the equivalent of noise on paper.

C.S. Lewis. . . he wrote a book called the Screwtape Letters. Probably the best thing he ever wrote. A series of radio broadcasts he did during WWII. . . about the time England was being bombed. The man was writing as if his life depended on it. The Screwtape Letters was written from the point of view of a demon helping out his nephew bring souls into Hell. Lewis wrote, somewhere in there, that there was no music in Hell. Only noise.

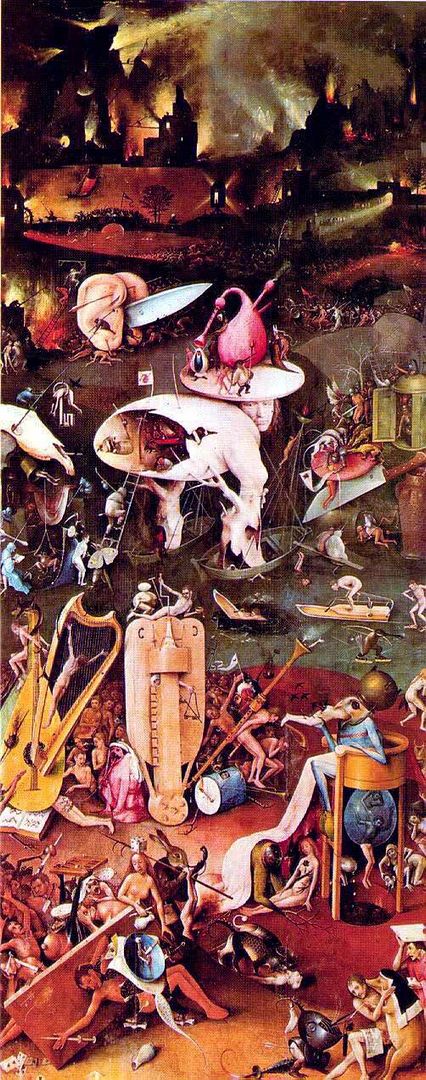

I was struck by that passage. Sometime later, I found myself looking over WORD. The poem became an interior monologue for one or any of the characters inhabiting Interzone. Take someone from such a Hellish environment. . . and there's a transcript of what runs through his or her mind. Take a figure of Bosch's Hell, a hell like that of Burroughs', where nature is perverted, where logic holds no sway, an inferno that consumes reason. There it is. It's WORD. There are no "complete" thoughts in Hell, no "finished" thoughts, either. . . Just words, words, words. . .

And, yeah, I'm comparing thought to music and the inability to think to noise.

Now, WORD is a sustained burst of this noise. It's peppered pretty liberally throughout Naked Lunch. . . but Naked Lunch gives your mind some traction, here and there. . . some lucid exposition, some characters in familiar situations. . . and then the noise springs up from the stereo and gets louder and louder, only to subside again. . . In his later novels, the noise was a little more fused with the prose. I'm thinking of stuff like his Dead Roads/Cities/Western Lands trilogy. In his first couple of Dashiel Hammett-style novels, it's not there at all.

But, there it is, the naked WORD.

When I finally got to Kerouac, it was the passages about meditating in the Dharma Bums that got me. Hit me in a way that I was reminded of the noise from Burroughs. Reminded of it because I'd finally encountered its (noise's, that is) opposite. Kerouac was the first author to sing to me.

More followed. More authors sang to me. I generally appreciate those works which lend themselves to performance by way of human voice. It became the standard by which I judge good prose. But to get a dose of the antithesis so early on. . . It was a shock to the system, at the time.

In vain, I look for a kick that's going to measure up to that one.

Hell, the right panel of Hieronymus Bosch's tryptech, The Garden Of Earthly Delights