1920 Movie #2: "The Flapper"

The Flapper

1920, USA, Selznick Pictures

Directed by Alan Crosland

Written by Frances Marion

Our next offering from 1920 is one of the few surviving films of one of the biggest movie stars of the late 'teens, Olive Thomas. Born in a Pennsylvania coal mining town to Irish immigrants, Thomas became a star in Broadway's Ziegfeld Follies, before moving on to a successful film career that lasted only a few years. The Flapper is one of her last films.

25-year-old Thomas plays Genevieve King, 16-year-old daughter of the very proper Senator King. They live in Orange Springs, Florida, described as "a town where they didn't even have a saloon to close." Genevieve gets in trouble with her dad when she sneaks off (in broad daylight) to the soda fountain (!) with young Bill Forbes, soon-to-be military cadet. (It's not that Bill's family is poor or anything. When they boat off to the Soda Shoppe, it's in a chauffeured boat!) The Senator decides to ship his daughter off to Miss Paddles' (!!!) boarding school "near New York."

(The part of "near New York" will be played by Lake Placid, New York, a mere 6 hours drive from the city. They needed to make sure they had snow, and for that job Lake Placid is your man.)

At the boarding school, Genevieve (soon re-christened Ginger, which is shorter to type, so thank goodness) gets on well with the other girls (who wear stockings! *gasp*). In their spare time, they participate in winter sports like sledding, skiing and ice skating. They also spend some time speculating about a certain dashing gentleman who rides past their school most days: Richard Channing. "They just knew he was notorious, or very gay, or perhaps an English lord..." the title card tells us, apparently not suspecting that these are not mutually exclusive descriptions. The girls suspect the man is a professional gambler, or an actor, or maybe a wife-beater. Ginger pooh-poohs this last one. She can tell he's not the type to be married.

In a grotesque miscalculation on the Senator's part, the school is right near the military academy that Bill is attending, so he and Ginger soon bump into each other while ice-skating. (No, not literally.) Bill now shows his unfortunate tendency to talk big and then try to back it up leading to some trick-skating hijinks, then culminating in a promise to take Ginger for a sleigh ride. Sadly, Bill knows nothing about horses, and ends up tipping the sleigh over, leaving Ginger in the snow while he runs after the horse. Fortunately for her, along comes Richard Channing in his sleigh, and offers her a ride. She pretends to be older than she is ("Ohhh, about twenty.") and complains about how she gets treated like a kid. Channing ends up inviting her to a dance at the Country Club that evening.

Everything's going swell, until one of the girls rats her out. Hortense, the school's token "poor girl" charity case, tells Miss Paddles that Ginger's gone to the party. Miss Paddles is aghast, and hurries to the country club to fetch her back. Hortense's real goal, however, is to take the opportunity of Paddles' absence to rob the school safe! You just can't trust these poor folks...

Ginger is mortified to have Miss Paddles retrieve her mid-dance, and Miss P wastes no time castigating Channing for "luring" a 16-year-old girl. As they're about to leave, Ginger runs back in to retrieve her fan, and overhears Channing complaining to his friends about "sap-headed, pin-feathered" kids. At this point, on her way out, Ginger has an oddly placed bit of business with a stuffed moose head in the lobby that I confess I didn't quite get. Was it a standard gag for moose heads in public places to have tricked-out winking eyes at that time? A bit of a laugh for the hat-check girl or whoever? It's utterly without context here.

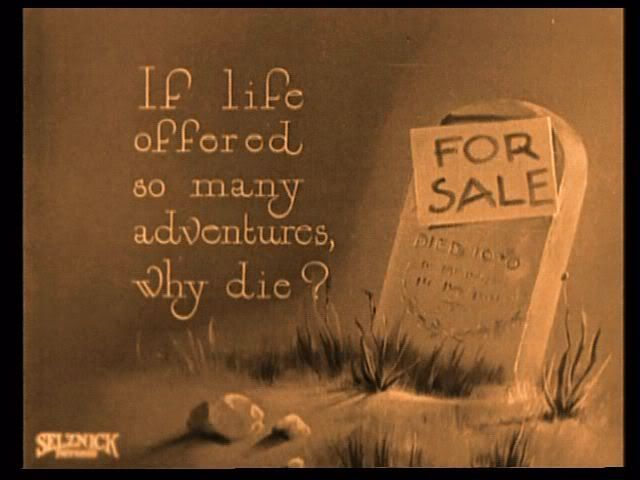

Returning to the school, Ginger decides to commit suicide by hanging. This little project is interrupted when Hortense's partner in crime drives up to abscond with her and the money and jewels from the safe. Overhearing this departure, Ginger rouses the school, though they fail to stop the thieves from leaving. (It occurs to me that this is also a good way to have a bunch of girls in pyjamas running around. Clever filmmakers...) Miss Paddles asks the girls to keep the theft quiet to protect the school’s reputation.

Now, here's where it starts to get contrived: The thieves begin to worry that someone will get on to them (most specifically, Channing, who's happens to be staying at the same hotel. They lure Ginger to New York City with an anonymous note which hints of adventure (Ginger’s new-found reason to live); give her a song-and-dance about the whole theft being a joke, and how they’ve already returned the jewels; and ask her to carry some bags back to her home, where they’ll pick them up later. During this time, Ginger has a chance encounter with Channing, in which Ginger tries to act worldly and sophisticated in order to “teach him a lesson,” and we learn he is, himself heading to Orange Springs with a (literal) boatload of friends. Looking in the thieves luggage (after being warned not to, of course) Ginger finds loads of jewels (but never seems to suspect a connection to the robbery) as well as fashionable clothes and a collection of Hortense’s love letters. Armed with this stuff, Ginger concocts her final “wacky” scheme: go home pretending to be a woman of “experience,” and teach them all a lesson…

When I was a young lad, I was under the impression that older films were stuffy, moralistic and dull. I think I mostly received this impression from films and TV that were slightly less old, which later turned out to be slightly stuffier, more moralistic and duller than most older films. Certainly the impression most people my age have of silent films is derived from sketches and parodies in comedy TV and films from the ‘60s and ‘70s, which hardly constitutes either documentary evidence or first-hand experience, given a tendency towards distortion for comedy’s sake compounded by lazy stereotyping. Add to this the fact that much material mocking silent film is based on impressions of the subject material learned from other parodies. (This same effect colors what many people think of westerns or black-and-white era detective movies. The clichés they are known for are more prevalent in parody than in the original material. Have you ever seen a serious western where two guys face each other for a formal duel on Main Street? I’ve seen movies that play off this cliché, such as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance or The Quick and the Dead but none that feature it straight up.)

Another factor in the “moralistic” impression of silent films is the broadcast standards of TV stations in the ‘50s. TV resurrected silent film in the name of filling the programming schedule, long after the movies had no further use for them (outside of specialized audiences.) The broadcast standards of most TV stations were at least as restrictive as the Hollywood Production Code, which hadn’t been enforced until 1935. Thus, many silent films would be unacceptable to TV standards. Plus, there’s the matter of how few survived the period where silents were commercially unviable, historical relics of a medium still not considered reputable enough to preserve. The films that survived tended to be unadventurous, innocuous, and/or the product of major directors/producers/studios. (Also, a few survived from sheer weirdness: Nosferatu and Caligari both spring to mind.) Two of the biggest directors of the silent age, D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, were prone to moralizing (though DeMille went about it in a two-faced kind of way, providing plenty of misbehavior before the assertion of morality at the end.)

What we have in The Flapper is a film that, if stripped of its title cards or viewed incompletely, might be mistaken for a morality play (though perhaps a puzzlingly comedic one,) but is actually quite the opposite. It’s a bit of mainstream comedic fluff, mocking the stuffy moralizers of society, flirting with impropriety, and, in the end, letting its troublesome and irresponsible young heroine off the hook, consequence free. If the film was made in recent years, it would star Lindsay Lohan, or Hilary Duff, or whatever young talent the Walt Disney company has imagineered since them.

The film, throughout, mocks the disapproval of the most uptight portion of society. The depiction of Orange Springs, and of Senator King and company, are gently sarcastic. They’re painted as ridiculous rather than hateful, but the film does seem to hold a suggestion that it is this repression of any fun at all that pushes young Ginger into the “trouble” she finds herself in later. There is some obvious irony in the Senator sending his daughter away to protect her morals, an action which allows her greater freedom than ever, and the film’s slightly snarky title cards don’t let that pass unsuggested.

Oddly, the film crosses a few lines which might be considered in very bad taste today. Ginger’s abortive suicide attempt is played entirely for laughs. There is not a hint of real tragedy about it, just an excess of teen-age melodrama (this is ably emphasized by the nicely-judged title cards.) Perhaps more troublesome in our modern cultural atmosphere is the flirtation between a 16-year-old girl and an older man. While Channing at no time seems serious about the flirtation (and later seems kind of irritated by Ginger), I find it hard to believe he fell for her feeble lie of being “about 20.” And finally, the film raises the idea of teenage pregnancy, however speciously it does so. This particular deception on Ginger’s part sends her father into a declaratively murderous rage, which helps fuel the low-octane farce of the films conclusion.

In the end, Ginger gets off with a stern scolding and a tiny bit of shame, and learns only the most perfunctory of lessons. I suppose this celebration of mild misbehavior might have rankled some of the stuffy moralists of 1920, and the parts mentioned in the paragraph above might twist the knickers of some of our 21st century equivalents. (The teen suicide gag would have garnered maximum outrage around 20 years ago…)

Leading lady Olive Thomas was a Big Deal in film back in 1916-1920. In 1914, she'd left her Pennsylvania coal-miner husband and headed for New York City. A job in a department store led to a job in the theater, specifically the Ziegfeld Follies. Olive made her biggest impression in the rather friskier Ziegfeld Midnight Frolics, and became somewhat notorious around town for fooling around with Flo Ziegfeld himself. (Ziegfeld was married to actress Billie Burke at the time, best remembered now as Glinda the Good Witch from the 1939 The Wizard of Oz.) In 1916, Olive started a spectacularly successful film career. In the remaining few years of her life, she appeared in 2 dozen features, starring in most of them. The Flapper was one of her last. On a trip to Paris with second husband Jack Pickford (womanizing party-animal kid brother of Mary Pickford), Olive mistook toxic skin treatment tablets for sleeping pills. Drink was blamed officially, but the celebrity tabloid press (yes, they had that back then, too) blamed Jack in vague and non-actionable ways.

And then most of her films were lost to time. Only ten are known to exist, and only one is out on DVD in the US. The DVD of The Flapper is labeled (perhaps optimistically) "The Olive Thomas Collection," and includes a full-length documentary called "Everybody's Sweetheart: The Olive Thomas Story" from which I got the info I've passed along here. The doc was produced by good ol' Hugh Hefner.

For more on Olive check out the Olive Thomas Homepage, or go to Olives's Myspace page.

1920, USA, Selznick Pictures

Directed by Alan Crosland

Written by Frances Marion

Our next offering from 1920 is one of the few surviving films of one of the biggest movie stars of the late 'teens, Olive Thomas. Born in a Pennsylvania coal mining town to Irish immigrants, Thomas became a star in Broadway's Ziegfeld Follies, before moving on to a successful film career that lasted only a few years. The Flapper is one of her last films.

25-year-old Thomas plays Genevieve King, 16-year-old daughter of the very proper Senator King. They live in Orange Springs, Florida, described as "a town where they didn't even have a saloon to close." Genevieve gets in trouble with her dad when she sneaks off (in broad daylight) to the soda fountain (!) with young Bill Forbes, soon-to-be military cadet. (It's not that Bill's family is poor or anything. When they boat off to the Soda Shoppe, it's in a chauffeured boat!) The Senator decides to ship his daughter off to Miss Paddles' (!!!) boarding school "near New York."

(The part of "near New York" will be played by Lake Placid, New York, a mere 6 hours drive from the city. They needed to make sure they had snow, and for that job Lake Placid is your man.)

At the boarding school, Genevieve (soon re-christened Ginger, which is shorter to type, so thank goodness) gets on well with the other girls (who wear stockings! *gasp*). In their spare time, they participate in winter sports like sledding, skiing and ice skating. They also spend some time speculating about a certain dashing gentleman who rides past their school most days: Richard Channing. "They just knew he was notorious, or very gay, or perhaps an English lord..." the title card tells us, apparently not suspecting that these are not mutually exclusive descriptions. The girls suspect the man is a professional gambler, or an actor, or maybe a wife-beater. Ginger pooh-poohs this last one. She can tell he's not the type to be married.

In a grotesque miscalculation on the Senator's part, the school is right near the military academy that Bill is attending, so he and Ginger soon bump into each other while ice-skating. (No, not literally.) Bill now shows his unfortunate tendency to talk big and then try to back it up leading to some trick-skating hijinks, then culminating in a promise to take Ginger for a sleigh ride. Sadly, Bill knows nothing about horses, and ends up tipping the sleigh over, leaving Ginger in the snow while he runs after the horse. Fortunately for her, along comes Richard Channing in his sleigh, and offers her a ride. She pretends to be older than she is ("Ohhh, about twenty.") and complains about how she gets treated like a kid. Channing ends up inviting her to a dance at the Country Club that evening.

Everything's going swell, until one of the girls rats her out. Hortense, the school's token "poor girl" charity case, tells Miss Paddles that Ginger's gone to the party. Miss Paddles is aghast, and hurries to the country club to fetch her back. Hortense's real goal, however, is to take the opportunity of Paddles' absence to rob the school safe! You just can't trust these poor folks...

Ginger is mortified to have Miss Paddles retrieve her mid-dance, and Miss P wastes no time castigating Channing for "luring" a 16-year-old girl. As they're about to leave, Ginger runs back in to retrieve her fan, and overhears Channing complaining to his friends about "sap-headed, pin-feathered" kids. At this point, on her way out, Ginger has an oddly placed bit of business with a stuffed moose head in the lobby that I confess I didn't quite get. Was it a standard gag for moose heads in public places to have tricked-out winking eyes at that time? A bit of a laugh for the hat-check girl or whoever? It's utterly without context here.

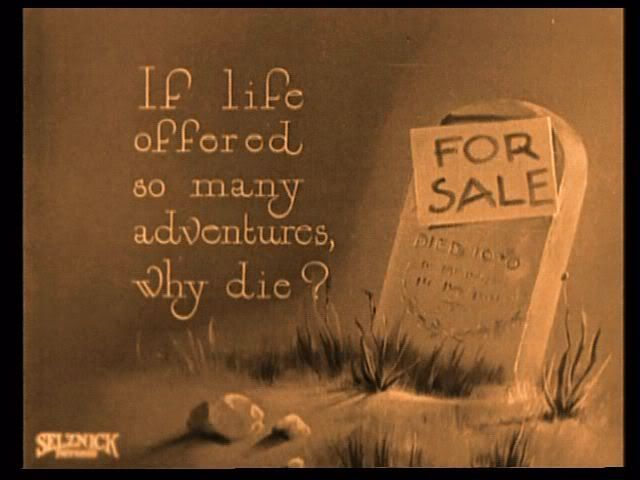

Returning to the school, Ginger decides to commit suicide by hanging. This little project is interrupted when Hortense's partner in crime drives up to abscond with her and the money and jewels from the safe. Overhearing this departure, Ginger rouses the school, though they fail to stop the thieves from leaving. (It occurs to me that this is also a good way to have a bunch of girls in pyjamas running around. Clever filmmakers...) Miss Paddles asks the girls to keep the theft quiet to protect the school’s reputation.

Now, here's where it starts to get contrived: The thieves begin to worry that someone will get on to them (most specifically, Channing, who's happens to be staying at the same hotel. They lure Ginger to New York City with an anonymous note which hints of adventure (Ginger’s new-found reason to live); give her a song-and-dance about the whole theft being a joke, and how they’ve already returned the jewels; and ask her to carry some bags back to her home, where they’ll pick them up later. During this time, Ginger has a chance encounter with Channing, in which Ginger tries to act worldly and sophisticated in order to “teach him a lesson,” and we learn he is, himself heading to Orange Springs with a (literal) boatload of friends. Looking in the thieves luggage (after being warned not to, of course) Ginger finds loads of jewels (but never seems to suspect a connection to the robbery) as well as fashionable clothes and a collection of Hortense’s love letters. Armed with this stuff, Ginger concocts her final “wacky” scheme: go home pretending to be a woman of “experience,” and teach them all a lesson…

When I was a young lad, I was under the impression that older films were stuffy, moralistic and dull. I think I mostly received this impression from films and TV that were slightly less old, which later turned out to be slightly stuffier, more moralistic and duller than most older films. Certainly the impression most people my age have of silent films is derived from sketches and parodies in comedy TV and films from the ‘60s and ‘70s, which hardly constitutes either documentary evidence or first-hand experience, given a tendency towards distortion for comedy’s sake compounded by lazy stereotyping. Add to this the fact that much material mocking silent film is based on impressions of the subject material learned from other parodies. (This same effect colors what many people think of westerns or black-and-white era detective movies. The clichés they are known for are more prevalent in parody than in the original material. Have you ever seen a serious western where two guys face each other for a formal duel on Main Street? I’ve seen movies that play off this cliché, such as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance or The Quick and the Dead but none that feature it straight up.)

Another factor in the “moralistic” impression of silent films is the broadcast standards of TV stations in the ‘50s. TV resurrected silent film in the name of filling the programming schedule, long after the movies had no further use for them (outside of specialized audiences.) The broadcast standards of most TV stations were at least as restrictive as the Hollywood Production Code, which hadn’t been enforced until 1935. Thus, many silent films would be unacceptable to TV standards. Plus, there’s the matter of how few survived the period where silents were commercially unviable, historical relics of a medium still not considered reputable enough to preserve. The films that survived tended to be unadventurous, innocuous, and/or the product of major directors/producers/studios. (Also, a few survived from sheer weirdness: Nosferatu and Caligari both spring to mind.) Two of the biggest directors of the silent age, D. W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, were prone to moralizing (though DeMille went about it in a two-faced kind of way, providing plenty of misbehavior before the assertion of morality at the end.)

What we have in The Flapper is a film that, if stripped of its title cards or viewed incompletely, might be mistaken for a morality play (though perhaps a puzzlingly comedic one,) but is actually quite the opposite. It’s a bit of mainstream comedic fluff, mocking the stuffy moralizers of society, flirting with impropriety, and, in the end, letting its troublesome and irresponsible young heroine off the hook, consequence free. If the film was made in recent years, it would star Lindsay Lohan, or Hilary Duff, or whatever young talent the Walt Disney company has imagineered since them.

The film, throughout, mocks the disapproval of the most uptight portion of society. The depiction of Orange Springs, and of Senator King and company, are gently sarcastic. They’re painted as ridiculous rather than hateful, but the film does seem to hold a suggestion that it is this repression of any fun at all that pushes young Ginger into the “trouble” she finds herself in later. There is some obvious irony in the Senator sending his daughter away to protect her morals, an action which allows her greater freedom than ever, and the film’s slightly snarky title cards don’t let that pass unsuggested.

Oddly, the film crosses a few lines which might be considered in very bad taste today. Ginger’s abortive suicide attempt is played entirely for laughs. There is not a hint of real tragedy about it, just an excess of teen-age melodrama (this is ably emphasized by the nicely-judged title cards.) Perhaps more troublesome in our modern cultural atmosphere is the flirtation between a 16-year-old girl and an older man. While Channing at no time seems serious about the flirtation (and later seems kind of irritated by Ginger), I find it hard to believe he fell for her feeble lie of being “about 20.” And finally, the film raises the idea of teenage pregnancy, however speciously it does so. This particular deception on Ginger’s part sends her father into a declaratively murderous rage, which helps fuel the low-octane farce of the films conclusion.

In the end, Ginger gets off with a stern scolding and a tiny bit of shame, and learns only the most perfunctory of lessons. I suppose this celebration of mild misbehavior might have rankled some of the stuffy moralists of 1920, and the parts mentioned in the paragraph above might twist the knickers of some of our 21st century equivalents. (The teen suicide gag would have garnered maximum outrage around 20 years ago…)

Leading lady Olive Thomas was a Big Deal in film back in 1916-1920. In 1914, she'd left her Pennsylvania coal-miner husband and headed for New York City. A job in a department store led to a job in the theater, specifically the Ziegfeld Follies. Olive made her biggest impression in the rather friskier Ziegfeld Midnight Frolics, and became somewhat notorious around town for fooling around with Flo Ziegfeld himself. (Ziegfeld was married to actress Billie Burke at the time, best remembered now as Glinda the Good Witch from the 1939 The Wizard of Oz.) In 1916, Olive started a spectacularly successful film career. In the remaining few years of her life, she appeared in 2 dozen features, starring in most of them. The Flapper was one of her last. On a trip to Paris with second husband Jack Pickford (womanizing party-animal kid brother of Mary Pickford), Olive mistook toxic skin treatment tablets for sleeping pills. Drink was blamed officially, but the celebrity tabloid press (yes, they had that back then, too) blamed Jack in vague and non-actionable ways.

And then most of her films were lost to time. Only ten are known to exist, and only one is out on DVD in the US. The DVD of The Flapper is labeled (perhaps optimistically) "The Olive Thomas Collection," and includes a full-length documentary called "Everybody's Sweetheart: The Olive Thomas Story" from which I got the info I've passed along here. The doc was produced by good ol' Hugh Hefner.

For more on Olive check out the Olive Thomas Homepage, or go to Olives's Myspace page.