1920 Movie #1: "The Last Of the Mohicans"

The Last of the Mohicans

Associated Producers Inc, USA, 1920

Directed by Clarence Brown and Maurice Tourneur

Scenario by Robert A. Dillon

Based on the novel by James Fenimore Cooper

And so we move onward, into the past, to 1920. And now I'm back on more familiar ground, review-wise. For we see before us another prime example of melodrama, though melodrama of literary pedigree. James Fenimore Cooper's books about the American frontier in the 18th century (which is to say, upstate New York) are held to be true American classics. Cooper's one of the earliest literary lights of the USA, at least by general reckoning. And what did he write? Adventure stories! Take that, metaphor and allegory!

So here we are, at the start of the 1920s, the Golden Age of the silent cinema. It's been 5 years since DW Griffith's legendary "Birth of a Nation" (the legend being that it was the first "real" feature film; this may be so for the US, but the Italians, and maybe others, were a couple of years ahead of us, as proven by films like "Cabiria" from 1914). Narrative film has developed a fair amount of sophistication, even among the less imaginative practitioners.

We open in 1757, in the Hudson River Valley. Our first characters introduced are Chief Great Serpent and his son Uncas, "remnants of a once huge tribe." (We'll see later that they're not literally "the last.") The Chief sends Uncas to warn the friendly palefaces down at the fort of their impending danger.

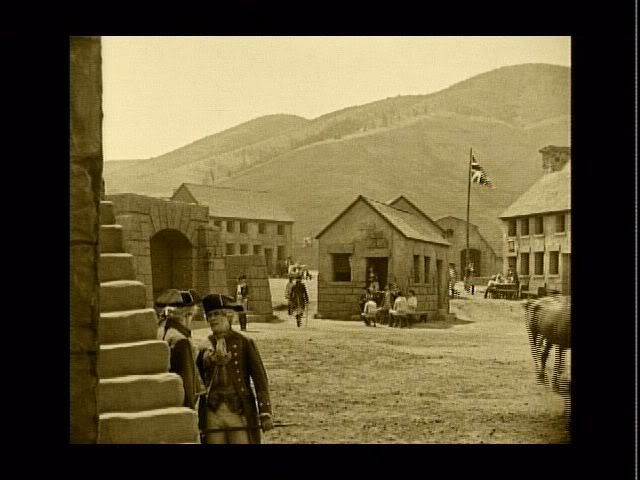

Down at Fort Edward, the English are having a little party. A title card tries to pass off dressing in excessively fancy clothes and playing a large and expensive harp surrounded by nice furniture and china place settings as "maintain(ing) the grace and dignity of life," rather than "failing to adapt to a new environment." Pity the poor enlisted blokes who had to lug that harp up the river for the colonel's daughter.

Here we meet several of our cast of characters: Cora Munro, colonel’s daughter and classy dame; her younger sister Alice, blond, delicate, useless; Captain Randolph, who “loves women more than war,” the scoundrel; and Major Heyward, Alice’s beau, handsome, brave, and kind of dull, really.

Just as the General (otherwise unnamed) is launching into a story (and it's amazing how well the actor gets across "pompous windbag" in complete silence), Uncas shows up to say that the Hurons are "on the warpath" and have "drunk the firewater of the French and have listened to lying tongues." So, basic movie Indian lingo was around back in 1920, then.

Cora takes a good, long look at Uncas (who is, after all, the only guy in the room not wearing a shirt… or a powdered wig, for that matter.) She decides a guy that good looking must be a prince. Native royalty cuts no ice with Capt. Randolph, who complains that a gal like Cora shouldn’t be “admiring a filthy savage.” (Cora’s admiration is portrayed as a rather intense and fixed stare. Not allowed to smolder too much back in the pre-Valentino days, I guess. Heaving of bosoms and licking of lips might be just a tad improper, savage prince or no savage prince.)

We cut to Fort William Henry, where the girls’ father is organizing the defenses. Here we find Magua, an Indian runner working for the English. He’s decidedly swarthy in comparison to Uncas and his dad. He also has a sort of evil clown face-paint, which is a further tip-off that this guy is not to be trusted. The Colonel is sending for reinforcements (3000 or so should do), and also for his daughters. The selfish old bastard wants to see them again before he dies, so he’s dragging them upriver into a war zone. Thanks, Pops.

Furthermore, so they don’t have to bear the company of all those enlisted men, he’s sending Magua to take them on a short-cut through the forest. Presumably, this is so they’ll arrive faster, but it still seems a little chancy. If I had daughters, I might rather have them guarded by 3000 soldiers; unless the idea is to protect them *from* 3000 soldiers.

Later, back at Fort Edward, Magua has arrived. Captain Randolph takes one look at him and decides his duty lies in the middle of 3000 heavily armed soldiers. If he was a better man, he’d rethink his “filthy savage” comment regarding Uncas, in light of Magua’s outstanding example of filthy savagery. (Randolph is not, however a better man.) Anyway, Major Heyward will go along with the gals to make sure Magua doesn’t get any ideas. (As we shall see, Magua is *always* getting ideas.)

Along the path, our four travelers run into David Gamut, a sort of wandering psalm singer (not exactly a preacher… I had to look this up. Apparently, he’s the 18th century equivalent of Christian Rock.) Gamut is sort of the comedy relief for this film. As such, he does very little that is humorous. Mostly, he makes funny faces, or starts to play his flute at inopportune moments when everyone else is trying to keep quiet. Ah, well, at least he doesn’t take up too much time.

As Magua leads our intrepid band through the woods, we catch an occasional glimpse of a sinister Huron or two watching from the bushes. (It seems Magua *is* a Huron, according to the novel. The film never makes this clear, as it would take a couple of cards at least to explain why he’s still employed, given the whole “firewater and lying tongues” thing.)

A sudden downpour causes our party of adventurers (they’ve even got a cleric!) to take shelter in a stand of trees, which is coincidentally already being used for shelter by Uncas, the Chief, and their pal Hawkeye, the scout. Hawkeye’s a lean, leathery dude in buckskins, who I was under the impression was a major character in the book. Here he’s kind of sidekicking for Uncas.

When our travelers tell the trio that their Indian guide is lost, Hawkeye retorts that Indians just don’t get lost in the woods. When he goes down to ask Magua about this, it turns out the guide has made himself scarce. (Magua is many things, most of which will get you 20 years to life, but he is no dummy.) “I suspect the varmint covets your scalps!” declares the old woodsman, perhaps too delicate to suggest that it’s not the *scalps* of the two young women they should be worrying about.

So it’s off to “a cave near Glenn’s Falls,” which I think is near a comic shop I used to drive to back when I lived in Middletown. Here our heroes (I’m comfortable using that word now that Uncas is back with us) hole up and hope the Hurons can’t find them. While Uncas watches for Hurons, Cora watches Uncas, adding a little half-smile to her intense staring routine. They even exchange some words regarding the sunrise. The title cards wisely tell us how thoughtful and wise Uncas’ words are, rather than trying to convey his exact words. It’s a nice dodge that sound pictures more or less removed from the director’s toolbox.

The Hurons attack, the gals are herded into the rear cave to load powder and shot, (well, Cora loads powder and shot, while Alice sort of just urges her on) and the men-folk shoot them some Huron. Eventually, they’re out of powder. After Hawkeye plugs a sniper up a tree, it leaves the sorry bastard dangling by one leg from a crook in the branch. Uncas uses their last shot for a mercy killing. He then concocts a daring plan whereby the men (meaning all the men but Heyward, who’s been injured, and Gamut, who’s pretty useless in this situation) will attack, and try to lead off the Hurons, saving the others.

Unfortunately, as I said before, Magua’s no dummy. Plus, he knows what he wants (and, as I implied before, it ain’t scalps.) The Hurons move in and take the four in the cave as prisoners. Then he helpfully informs them that “Magua does not kill his prisoners - he tortures them.” (Note the restraint used in a lack of an exclamation point in that sentence. That’s the difference between pulp and serious literary drama, right there.) They haul them off to a deserted blockhouse (reusing part of the fort sets, I guess) where Magua makes it clear what he does want: Cora. “If you would save the Yellow Hair, consent to be my squaw!” (That’s a fully justified exclamation point, there. Still serious literary stuff, yep.) “(L)et us die together!” cries Alice, causing Cora to look at her warmly, or maybe dubiously. It’s hard to tell.

Fortunately, the heroes show up and save everyone’s hash in another frantically violent action scene. After clashing hand-to-hand with Uncas, Magua escapes after falling down a hill and playing dead. (He *has* got blood all over him, so I’ll forgive Uncas and his pals for this one. But they’ll pay for their sloppiness later.) Add “tough as Hell” to Magua’s list of pluses.

Off to Fort William Henry, where Capt. Randolph takes personally the whole Cora-and-Uncas thing that’s developed. He figures it reflects badly on him (which it does, of course, but only incidentally). After a little shouting match between Randolph and Cora, Cora is left alone in her room at night. Hearing a noise at the window, does she draw back, hand over her mouth, ready to scream? Hell, no. She goes for the nearest rifle. Good girl, Cora! It’s just Uncas, so it’s a good thing she knows how to hold her fire. More chaste lovey-dovey stuff ensues.

A conference of Munro’s officers reveals that the guns on the east side of the fort are useless, and it’s a good thing the French don’t know that, or they’d all be massacred. Randolph decides that he’d better tell the French so *he* won’t be massacred, and off he goes to speak to General Montcalm. Monty takes his info, and calls Munro to talk. Montcalm says he knows their cannon are crap, but he’ll let them go if they leave without a fight. Also, he and the Huron chiefs promise safe passage for the women and children. (Nice guy, really.)

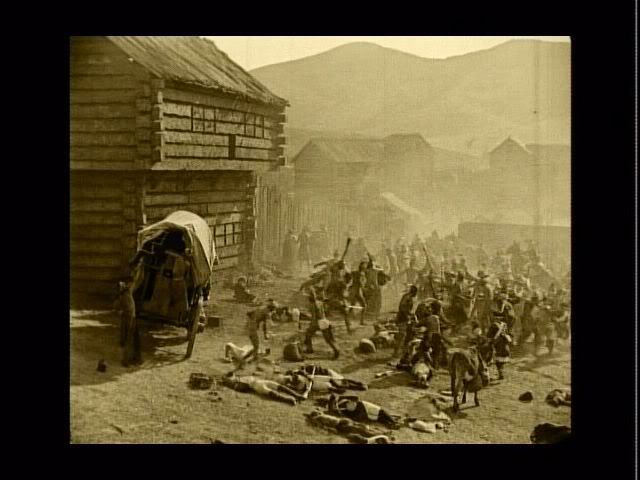

So far, so good, but the rank-and-file Hurons are full of two things: French firewater and Magua’s bad influence. Pretty soon, their big pre-battle bonfire party turns into a heady bout of raping and pillaging. (And horse-killing, baby-tossing, and holding a knife sideways in your mouth like a pirate. Good times.) The fort is in ruins, and Magua gets away with Cora and Alice (who were in the “women and children” part of the caravan. Meanwhile, Randolph gets caught in the slaughter, and hides in an underground store room, which turns out to be labeled “Danger - Magasin a Poudres.” (Not sure why it’s in French, if this is the English fort.) A Huron drops a torch down there to see who’s in there, and… well, you’ve seen enough Bugs Bunny cartoons to know what happens next, right?

With Uncas and company in pursuit, Magua runs to the peaceful Delaware tribe, who offer him sanctuary when Uncas, et al come calling (laws of hospitality and all that.) The Delaware set up a tribunal of wise men to hear the case, and they make their fair and impartial decision: Uncas should, indeed, get Cora, but there’s no reason for Magua to leave empty handed. He gets to take Alice. This does not sit well with our heroes, and Cora insists she should go in Alice’s place. (Alice has already fainted, so there’s no “Let’s die together” this time.) Magua’s got sanctuary ‘til sundown, so he gets a head start, but Uncas puts him on notice: he’s coming after them once it’s dark.

So, our second climax: the chase into the mountains (which look a lot more Sierra Nevada than Adirondack.) Cora escapes up to a cliff, where she ends up in a stand off with Magua: “Come closer and I’ll jump!” vs. “You’ve got to sleep sometime.” Uncas catches up at daylight and the final struggle begins…

So what we have here is an adventure tale, yes (and a good one), but also a fine example of the sub-genre of “period romance.” (That’s romance meant more in the modern “Harlequin” since than in the Alexandre Dumas sense.) We’ve got a number of clichés which appear throughout, including: heroine of respectable background (officer’s daughter); exotic but acceptable love interest (he’s an Indian, but he’s the chief’s son); the unsavory rival (two of them: Magua and Randolph); and the heroine’s opportunity for noble self-sacrifice, which seems to have been the only acceptable heroism for women up to a certain point. (To Cora’s credit, she almost takes direct physical action at a couple of points. Almost…)

Another interesting point of the film is the relatively fair and even-handed treatment of Native Americans it portrays. Uncas is noble, brave, loving, thoughtful, humane, etc. He is the undisputed hero of the peace, and fully worthy of Cora’s admiration. (And Randolph’s “filthy savage” comment thoroughly tars him as a rotter in consequence.) The Huron chiefs promise safe passage to the women and children in good faith. (As does General Montcalm, who comes across as honest and honorable, so the film is even nice to the French!) The Delaware tribunal is presented as fair and civilized, despite their odd judgment in the Magua vs. Uncas case. (I rather want to know the legal reasoning behind their decision, actually…)

So what about that horde of vicious, baby-killing Huron braves, you ask? Well the film places the blame for that atrocity squarely in two places: the rabble rousing of Magua (who is a completely, utterly, evil man, no question), and the influence of… Demon Rum! The ol’ French firewater is the culprit, apparently. There’s a strong implication that they wouldn’t have lost their cool if they hadn’t given in to intemperance. Yes, this is a Prohibition era movie, and unlike Prohibition comedies, where booze is hilarious, a mainstream drama is more likely to toe the line on “official” morality. (Compare the drug use in the average late seventies/early eighties campus comedy with the attitude towards drugs in the average cop drama or action film of the same period.)

The characterization of Magua, and the behavior of some random Hurons during the raid, raise the specter of that dreaded racist cliché: white women despoiled by “lesser” races. However, the cliché fails to fully manifest, due to the balancing portrayal of other Native American characters, Uncas in particular. Indeed, the film doesn’t quibble about whether the attraction between Cora and Uncas is right or not: they are the most admirable people in the film, moral, strong and selfless. Of course they belong together.

Mind you, this enlightened POV is, in turn, undermined by their status as doomed lovers, destined to a tragic end. Whether this was a sop to parts of the contemporary audience who might object to the pairing, or merely a reflection of Cooper’s original storyline, I do not know. (I really must read that novel…) Still, in comparison to 1930’s “Golden Dawn,” (in which it’s OK for the Englishman to love the African girl because she’s was actually white all along) this film is a paragon of racial sensitivity. Does this reflect a difference in how those of Native American descent were perceived relative to those of African descent? Or an erosion of egalitarianism across racial lines between 1920 and 1930? Or merely a difference of opinion between individual filmmakers? How much of this attitude towards the characters belongs to the filmmakers, and how much to Cooper? It is often difficult to separate cultural beliefs from personal, when viewing the product of a foreign culture (a category which certainly includes the USA of 1920, as easily as, say, the UK right now.)

Visually, the film looks pretty good for its time. The camera is stationary, but the performers are not, and there is a good amount of intra-scene cutting, cross-cutting, etc (which may not seem like a big deal, but these editing techniques were less than ten years old.) I watched the Lumivision DVD “special Edition,” which is copyrighted 1992(!), apparently justified by the musical score, new credit sequences (grumble, grumble) and a nice tinting job (which may or may not recreate the original tinting, but what the hell, it works...) Regarding the piano-centric musical score, I fell asleep twice trying to watch the film (not at all the movie's fault; our sofa is quite comfy), only succeeding when I turned the sound down.

The only cast member of note is Wallace Beery (Magua), who appears here in the phase of his career when he was playing lots of heavies. Beery later specialized in big, dim-witted but easy-going lugs, winning a Best Actor Oscar for 1931's “The Champ.” He's best remembered as Long John Silver in the 1934 “Treasure Island.” And yes, he's the half-brother of Noah Beery, who so appallingly portrayed Shep in “Golden Dawn.” I guess unflattering “race” roles run in the family.

(I guess I should mention Yosemite National Park, which overplays its role as the Adirondack Mountains. Lovely and majestic, yes, but a little too lovely and majestic, you know?)

Next up: “The Flapper,” the last(!) film of silent film star Olive Thomas. Can't get more 1920s than that...