THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 8 - Spiritual canonicity...

Оригинал взят у mmekourdukova в THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 8 - Spiritual canonicity...

Spiritual canonicity of the icon, spiritual physiognomy of the iconographer

Not all images created and presented by an artist are accepted by the Church. Indeed it even happens that among icons already blessed and exhibited in a church, some are so disturbing that they are rapidly adjusted or repainted, and even destroyed, even if the iconographic canon has been adhered to without reproach. And was we have seen in the previous paragraph, style in the meaning of the style of a particular era or geographic area, is no bar per se to canonicity.

What can be the cause of this censorship, if this is not the iconography or the style? So what is the additional criterion that determines the trueness or canonicity of the icon? What have we omitted? What can otherwise be found in icon to be incorrect, contrary to the Spirit that irrigates the Church?

This criterion is the internal and spiritual correspondence of the iconic image to the truth guarded and taught by the Church. We call it here the spiritual canon. It is also referred to in other writings as the anthropological canon. It is important not to confuse this spiritual canon with the iconographic canon. Nor is it linked to any one of the great styles of the past, rather it relates to the individual style of the particular artist, within the wider framework of the general style, of a particular period or geographic area that the latter has opted for, this individual style reflecting the artist’s personal spiritual physiognomy. This physiognomy can be properly structured, or can be contrary to and at odds with the message of Church, thereby confirming or vitiating to a greater or lesser extent the spiritual power of the icon. The chief defect of the «theology of the icon» of Leonid Uspensky and his kind is its ignorance of this notion of spiritual canon. Without it, any concept canonicity is incomplete. To understand it better, let us remind ourselves of two episodes in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church, in which she defended the true meaning of the icon.

In 1884, the young Mikhail Vrubel, who had just finished his studies at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, received a prestigious commission: the iconostasis of the Church of St. Kirill in Kiev. He produced two large icons, one of the Savior and the other of the Mother of God, in the usual style of his time for sacred art: careful Academic drawing, realistic treatment of the forms, traditional iconographic schemes both for the poses of the figures and for the colors of the clothes and the presence of gilding, haloes and inscriptions. And yet his icons were never blessed.

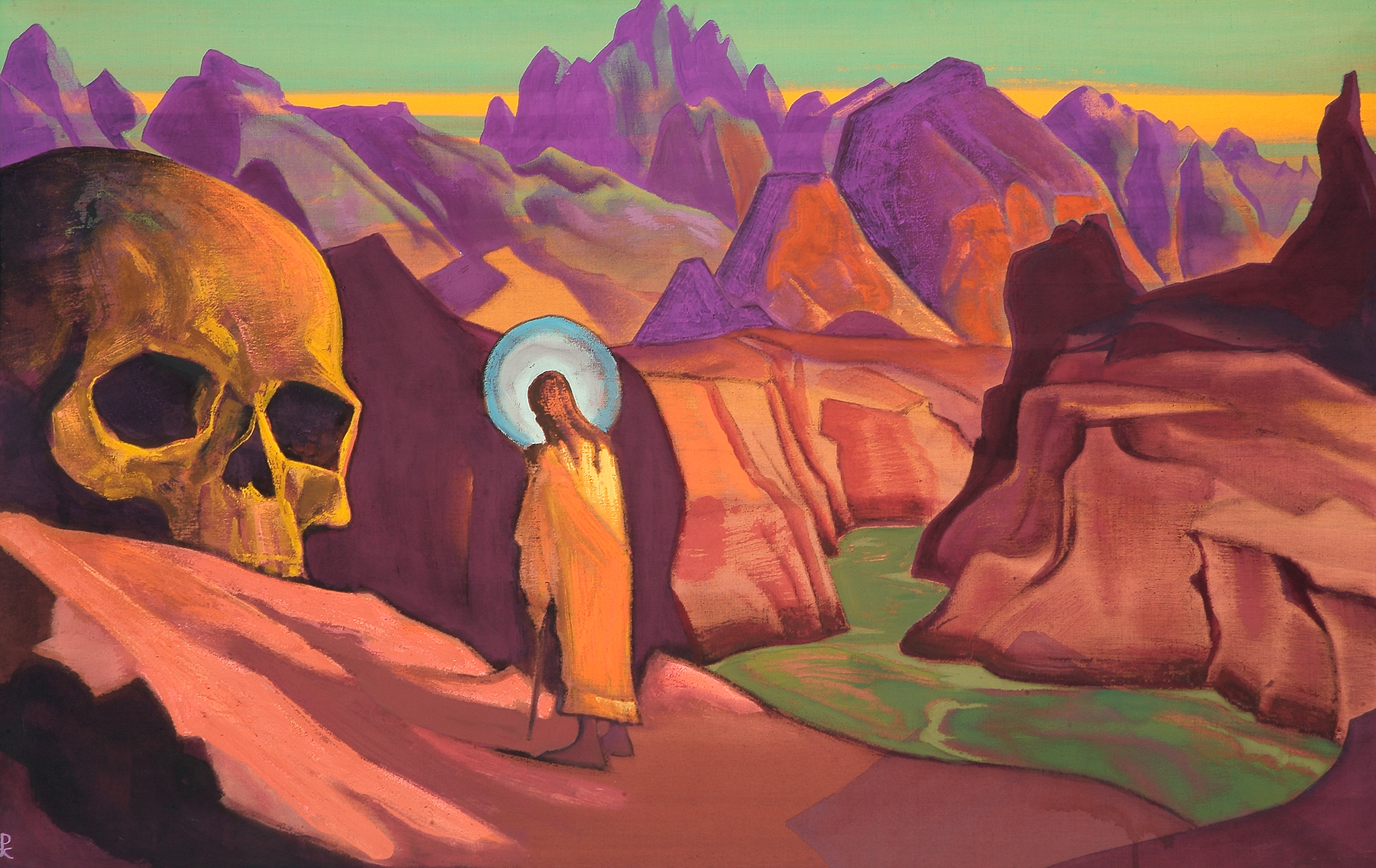

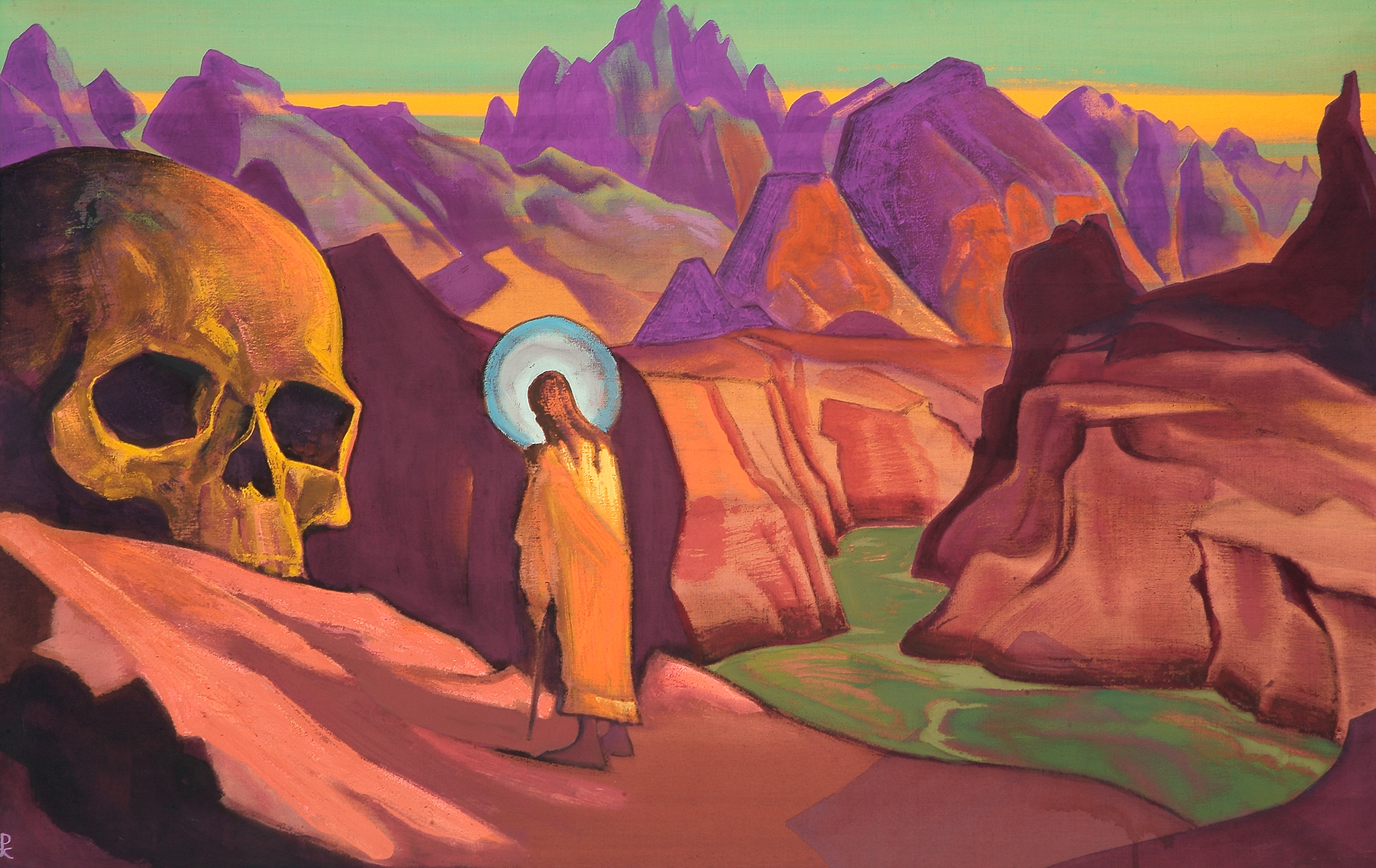

Why was the work of a painter of this quality refused, not recognized as «icon», and its use as an object of devotion prohibited? Did the reason lie in the technical quality of his work? Certainly not! Could it the presence of zhivopodobiye («resemblance to the living»)? No that either! Before giving the real reason for this rejection, let us look at another, even more outrageous example. This time, we are dealing not just with an iconostasis, but an entire full church, with its frescoes and mosaics, which was declared unworthy of consecration. This huge and very expensive work not only remained unfinished, but also rendered impossible worship within the walls where religious services could have been celebrated if they had remained simply plastered and painted brick. We are talking of the village church of Talashkino, built in 1910 by Princess Marie Tenisheva, a wealthy patron of the arts. This church, still visible in this village in the Smolensk region, is decorated both inside and out with mosaics and frescoes by Nikolai Roerich. To his credit we have to say that his work is of superb quality. The iconography was canonical and the style «Byzantine» - in those years, Roerich was passionately interested in ancient Russian culture and he poured into this project everything he admired in the Byzantine tradition. But why then was his work were rejected by the Church? Which canons did they transgress?

One thing is obvious: the Church could not possibly recognize in Roerich's work the truths it teaches about the Lord, about His Mother, or the saints. Why? Because the spiritual canon was not respected.

And how was it not respected? The gigantic image of Christ not-made-by-human-hand) on the tympanum of the church of Talashkino, stares at passers-by with a tense and menacing air. His protruding, wide-open eyes; his face furrowed with sharp shadows around the nose, his brutal features, flattened and dryly symmetrical, all this inspires only fear. In no way do these traits evoke, in the viewer's soul, the image of a living God, full of love, light and wisdom. No internal harmony emerges, only the image of a terrible idol, inaccessible to prayer, the enemy of man, grotesque and terrifying. The same applies to the frescoes inside the church. Fortunately they quickly disintegrated apart after their completion. The figures represented were frozen and sullen. An icy breath emanated from their faces frozen in impenetrable masks. An overwhelmingly oppressive impression would have seized any believer attempting to venerate these morbid images.

Roerich, who painted so successfully pagan Russia, whose glossy panels described the old North of fable, had allowed himself to apply in a church, and for a private commission, the same decorative and romantic approach. The Christian faith was for him, as unfortunately for his sponsor, just one facet of the «Russian soul. » Most members of the Russian intelligentsia of that time were interested in religion and spirituality only as a delicate cultural pleasure: for them it was merely a beautiful myth that pleasantly tickled their imagination, but it was not life. Let us quote an excerpt from Princess Tenisheva's Memoirs. These lines were inspired by a Vespers service celebrated at her home for her family and guests.

"I wanted to celebrate the feast of my guardian angel in a Christian manner, in the old way. It was like a breath on my soul, reminding me of the forgotten days of this ancient time in the life of the manor house, when our ancestors accompanied every family celebration with prayer ... The audience was also in a good mood, not to mention the servants, who are always softened by these forgotten but so moving habits."[1]

One cannot be clearer. Any anti-religious pamphleteer could have signed this naive blasphemy. For our sponsor, a liturgical celebration is nothing more than a curious forgotten habit that in bygone years added luster to family celebrations, and remains so moving for domestics. And here now a totally different page of her Memoirs. She decides to do something good for these little people: to have a church built for them, while improving their taste. What enthusiasm, what confidence in her beneficial mission! She tells how she came to knew Roerich and under what circumstances she entrusted him with the decoration of the church of Talashkino.

"As soon as I spoke, he seized my words.[2] And this word, it was 'A church ...!' "If the Lord allows it, it is with him only that I will finish it. This is a man who lives in the Spirit, who has received the spark of the Lord, and it is through him that the divine truth will come. The building of the church will be completed through the power of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is the strength of the spiritual joy of God, binding and enveloping the Cosmos with its mysterious power. What a task for an artist! What scope for the imagination! How his creativity will be able to apply itself to the church of the Spirit! We understood each other! Nikolai Konstantinovich fell in love with my idea, he understood the Holy Spirit. Amen. Right along the road from Moscow to Talashkino our friendly dialogue continued, elevating our thoughts and our plans to join Infinity. Oh, these holy minutes, full of grace...!«[3]

Anyone with any familiarity with Orthodox spirituality recognizes the symptoms of this kind of hysteria. The state of the soul of our princess could simply be described as prelest and at an already well advanced stage! Prelest is the Russian term which designates spiritual delusion, a state considered more dangerous than the worst sin in Orthodox ascetical theology. And it is in this spirit that the church construction project was had been conceived and the frescoes were sketched out and implemented!

The princess describes in detail the evolution of her ideas, the sleepless nights spent on her project, her efforts to express her nostalgic ideas about «forgotten things» and the emotions of a bygone era. Neither she nor Roerich doubted at any stage the spiritual quality of their work. They sought no advice, whether from priest, professional iconographer, or theologian. This church belonged to them and them only. Every time the Princess speaks of it, it is: «my church, my temple.» And Roerich for this commission gives free rein to his creative desire to express the national art nouveau.

In this context it was primarily the interior poverty and impiety of this approach that outraged the representatives of the Church hierarchy. Whereupon they unsurprisingly refused to recognize and bless the decoration of the church of Talashkino. The lack of spiritual canonicity of Roerich's works was neither masked nor compensated by its having respected the iconographic canon or being in the Byzantine style.

Vrubel, by contrast, had not compensated or hidden anything. The Academic style does not lend itself to what his intentions. His goal was the expressiveness of a realistic image, and the image of the Mother of God is indeed highly expressive. But how do we sense these parched lips, this childish face with pleading, black-outlined eyes, and these thin nervous fingers? The dominant impressions are of naive sensuality, abandonment to sin, of submission to the passions, but also this constant nervousness that so often marks Vrubel’s secular works, this painful fracture of refined natures, destined for the sublime, but compromised by their turning away from the destiny intended for them, and repeated again and again in portraits, paintings, and decorative panels. By attributing to the Mother of God the traits that attracted and fascinated him in women, Vrubel committed a serious spiritual error. But in addition, as the documents of the time tell us, he had placed himself in a highly delicate situation. Falling in love with the young wife of his patron A.V. Prakhov, in whose house he was living, the brilliant young bachelor courted the young woman, all of which ended in a violent quarrel between the artist and his patron.

In the icon rejected by the Church we find the charming, childlike features of Madame Prakhova who had served as a model. It was not, however, the fact of painting from a live model [4] which prevented the icon being accepted, but rather the sentiments transferred from the model into the sacred image - nervousness, anxiety, passionate excitation - deemed by Vrubel to represent real spirituality, but very far from the vision of the Church. These feelings, having become the leitmotif of his painting, are expressed in his work by mythological images, including the figure of Vrubel's main hero, the Devil. These morbid and dangerous spiritual games ended in mental illness, blindness, and an early death. It is rare to see someone punished in his lifetime, and so visibly, for his apostasy.

Unlike Vrubel, Roerich lived a long time, enjoying recognition and fame. His renunciation of the truth of the Church subsequently turned into active opposition, with Nicolai and his wife Helena becoming widely known occultists in the wake of the famous theosophist Helena Blavatsky. In his subsequent paintings and panels, mystical landscapes of Mongolia, India and Tibet replace the villages of Old Russia. They express a very special spirituality, aggressive, devoid of humanity, and deprived of God, the same spirituality that had denatured the frescoes and mosaics of Talashkino and had left the church unconsecrated.

These two examples are important for understanding the specificity of the spiritual canon, because the two creators were first-rate artists, with their own styles perfectly expressing their very personal spirituality, along with the apostasy characteristic of their mental structures. The quality of their artistic technique made them quite capable of accurately expressing what they felt and thought they knew. It is visible that in their eyes the Lord, his Mother and the saints are not full of goodness, peace, and joy. The depiction of them radiate neither love, nor mercy, nor consolation. If the Academic painter Vrubel shows them at least as beautiful and intelligent, the Byzantinist Roerich makes them also disturbing, stupid and ugly.

A certain «theology of the icon» ignores this notion of «psychic» (= of the soul) discernment, believing as it does that both icons and iconographers float in the field of pure spirit. It seems to us, however, vitally important to assess the spiritual value of any icon, in particular any icon which is going to be critically involved, through prayer in front of it, in a person’s soul life. According to Orthodox ascetic theology it is through our soul that we gain access the invisible world, that ‘a well of living water springs up to eternal life’ (John 4.14), that the fruits of the spirit - love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trust, gentleness, self-control (Gal. 5.22) - begin to exhibit themselves, and that we begin to «see God» (Matt. 5.8). The depth of this access is critically dependent on the purity, not only of our own soul, but also of any other person playing an intimate intermediary role in this access (an artist painting an icon a person prays in front of, a priest hearing the same person’s confession etc.). What happens (or should happen) when an icon is presented to the priest to bless it, is a discernment of the ability of the icon to serve as in this intermediate role, and in particular of any feature that could block or distort this communication. We would insist that such discernment is not only permissible, but is spiritually essential.

As long as we remain in the world here below, we cannot judge the invisible world other than through the soul (the psyche). Saint Paul, in his Epistles, teaches us the «psychic» terminology as a discipline giving prominent place to the Holy Spirit and by which we avoid the pitfalls:

For the time is coming when people will not put up with sound doctrine, but having itching ears, they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own desires, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander away to myths. (2 Timothy 4: 3-4)

We sinners have a tendency to follow the wrong roads:

«Delighting in humble devotional practices, in worship of angels, this one gives full attention to his visions, puffed up in vain pride by his fleshly mind. (Colossians 2: 18)

To muzzle this excess, the apostle keeps coming back to «psychic» benchmarks in the field of the spirit:

But here is the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trust, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law. (Galatians 5. 22-23)

For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Walk as children of light. And the fruit of light is called goodness, justice, truth. Learn what is pleasing to the Lord. Do not associate you with the unfruitful works of darkness; but instead expose them. (Ephesians 5, 8-11)

Finally, brethren, all that is true, noble, just, pure, whatever is lovely, honorable, whatever is called virtue and deserves praise; this is what you should concern yourselves with. (Philippians 4, 8)

We ask God that you will have full knowledge of his will in all wisdom and spiritual understanding; for you to lead a life worthy of the Lord, seeking his total approval. By everything good that you do, you will bear fruit and make progress through the true knowledge of God; you will be strengthened in every respect with the force of his glory and led in this way to perseverance and longsuffering with joy.

(Colossians 1. 9-11)

For Orthodox Christians, holiness and spirituality are not abstract, but concrete and positive notions, recognizable by certain qualities and moods. The liturgical texts and prayers of the Orthodox Church abound in psychic terms. This means that we can also require that the icon provide a correct, canonical image of God, in the same «soul» terms. If the character depicted on the icon, even if crowned with a halo and provided with suitable inscriptions, looks nasty, aggressive, powerless, ugly or stupid, the spiritual canon of the Church regarding the ideal representation of God is brutally violated, just as seriously as the iconographic canon would have been if that character had given a blessing with the left hand or was wearing a tuxedo.

The theology of the icon needs to try to understand how the images of the world and of man, passing through the filter of the artist's soul, and expressed with care and respect by his or her hand, are transformed into expressions of spirituality. It is precisely this phenomenon, at once the most subtle and the more specific, that a true theology of the icon ought to treat of, because it touches on the ontology of the icon, on the miracle of the incarnation of the psychic which leads to the spiritual level, an incarnation brought about by material things as simple as a board and a little paint. How do we define why sometimes this expression of spirituality at times takes us to heaven, and at other times hurls us into hell? What has the artist done with his object? How has he transfigured it? No theology has to date properly examined this field.

It is time to lay the roots of a serious theology of art in general and of the art of the icon in particular. This science has to be founded by the combined efforts of Christian anthropologists, Christian theorists of the fine arts, and Christian theologians. The absence of this science has been and continues to be very harmful not only for sacred art, but for art in general, because of course all art is spiritual, and all artistic creation is a spiritual activity. Vladimir Weidle, an eminent thinker of the first Russian emigration, called art "the mother tongue of religion«[5], reminding us with finesse and precision that the true specificity of art is the realm of the invisible, the field of deep feelings that are expressed in artistic images, feelings that no verbal mode of expression is able to express.

At the same time, spiritual activity and asceticism are considered in the tradition of the Church not as a science or as a sport but rather as an art. The Philokalia (that is to say Love of Beauty), a classic collection of works on Orthodox asceticism, confirms to us that Beauty is well recognized as a spiritual category. In the icon, we come to the knowledge of the Spirit through visible beauty, but this beauty (the beauty of a concrete art style and the beauty of a concrete person represented) is itself generated by the spirituality of the artist which it reflects. This artist has developed his individual style in the framework of the school and tradition to which he belongs, also it is he that lends to the sum a facial features a particular expressivity, conceived in advance and rendered with great effort. And it is in doing this that the artist’s mission towards the Church and the world lies, today and in the future.

At this stage we must take care to avoid vulgar simplification. While an artist's spiritual physiognomy is not fixed «automatically» in his work as a photographic plate (and an amateur who has not mastered his art cannot possibly fix his spiritual physiognomy, simply because he will be unable to fix anything), a gifted artist, carefully trained in a specialized school, will acquire the ability, not only to paint the visible universe, but also to express, almost despite himself, the invisible universe, including his own spiritual physiognomy. Through his training in a specialized school, the artist-in-becoming will benefit from the spiritual acquis, that is the accumulated experience and knowledge, of the school, through imitating the art and, with it; the spirit of his teachers. This is how the mechanism of the blossoming out and development of the great historical styles of the past took place.

So, how should an iconographer be trained? How does one receive the spiritual tradition via the artistic tradition? That is the subject of the next chapter.

[1] Princess M.K. Tenisheva, Впечатления моей жизни. Leningrad, 1991, p 126.**

[2] It comes as not surprise that Roerich had jumped at the opportunity, since his commercial genius was on a par with his artistic talents ...!

[3] Princess M.K. Tenisheva, op. cit. p. 250

[4] Other academic painters also painted from live models: Nyestierov, Vasnyetsov ... and their works were accepted by the Church.

[5] V. Weidle, Искусство как язык религии, in Le Messager (A.C.E.R.) n° 50, Paris-New York, 1958, pp. 2-10

Spiritual canonicity of the icon, spiritual physiognomy of the iconographer

Not all images created and presented by an artist are accepted by the Church. Indeed it even happens that among icons already blessed and exhibited in a church, some are so disturbing that they are rapidly adjusted or repainted, and even destroyed, even if the iconographic canon has been adhered to without reproach. And was we have seen in the previous paragraph, style in the meaning of the style of a particular era or geographic area, is no bar per se to canonicity.

What can be the cause of this censorship, if this is not the iconography or the style? So what is the additional criterion that determines the trueness or canonicity of the icon? What have we omitted? What can otherwise be found in icon to be incorrect, contrary to the Spirit that irrigates the Church?

This criterion is the internal and spiritual correspondence of the iconic image to the truth guarded and taught by the Church. We call it here the spiritual canon. It is also referred to in other writings as the anthropological canon. It is important not to confuse this spiritual canon with the iconographic canon. Nor is it linked to any one of the great styles of the past, rather it relates to the individual style of the particular artist, within the wider framework of the general style, of a particular period or geographic area that the latter has opted for, this individual style reflecting the artist’s personal spiritual physiognomy. This physiognomy can be properly structured, or can be contrary to and at odds with the message of Church, thereby confirming or vitiating to a greater or lesser extent the spiritual power of the icon. The chief defect of the «theology of the icon» of Leonid Uspensky and his kind is its ignorance of this notion of spiritual canon. Without it, any concept canonicity is incomplete. To understand it better, let us remind ourselves of two episodes in the history of the Russian Orthodox Church, in which she defended the true meaning of the icon.

In 1884, the young Mikhail Vrubel, who had just finished his studies at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, received a prestigious commission: the iconostasis of the Church of St. Kirill in Kiev. He produced two large icons, one of the Savior and the other of the Mother of God, in the usual style of his time for sacred art: careful Academic drawing, realistic treatment of the forms, traditional iconographic schemes both for the poses of the figures and for the colors of the clothes and the presence of gilding, haloes and inscriptions. And yet his icons were never blessed.

Why was the work of a painter of this quality refused, not recognized as «icon», and its use as an object of devotion prohibited? Did the reason lie in the technical quality of his work? Certainly not! Could it the presence of zhivopodobiye («resemblance to the living»)? No that either! Before giving the real reason for this rejection, let us look at another, even more outrageous example. This time, we are dealing not just with an iconostasis, but an entire full church, with its frescoes and mosaics, which was declared unworthy of consecration. This huge and very expensive work not only remained unfinished, but also rendered impossible worship within the walls where religious services could have been celebrated if they had remained simply plastered and painted brick. We are talking of the village church of Talashkino, built in 1910 by Princess Marie Tenisheva, a wealthy patron of the arts. This church, still visible in this village in the Smolensk region, is decorated both inside and out with mosaics and frescoes by Nikolai Roerich. To his credit we have to say that his work is of superb quality. The iconography was canonical and the style «Byzantine» - in those years, Roerich was passionately interested in ancient Russian culture and he poured into this project everything he admired in the Byzantine tradition. But why then was his work were rejected by the Church? Which canons did they transgress?

One thing is obvious: the Church could not possibly recognize in Roerich's work the truths it teaches about the Lord, about His Mother, or the saints. Why? Because the spiritual canon was not respected.

And how was it not respected? The gigantic image of Christ not-made-by-human-hand) on the tympanum of the church of Talashkino, stares at passers-by with a tense and menacing air. His protruding, wide-open eyes; his face furrowed with sharp shadows around the nose, his brutal features, flattened and dryly symmetrical, all this inspires only fear. In no way do these traits evoke, in the viewer's soul, the image of a living God, full of love, light and wisdom. No internal harmony emerges, only the image of a terrible idol, inaccessible to prayer, the enemy of man, grotesque and terrifying. The same applies to the frescoes inside the church. Fortunately they quickly disintegrated apart after their completion. The figures represented were frozen and sullen. An icy breath emanated from their faces frozen in impenetrable masks. An overwhelmingly oppressive impression would have seized any believer attempting to venerate these morbid images.

Roerich, who painted so successfully pagan Russia, whose glossy panels described the old North of fable, had allowed himself to apply in a church, and for a private commission, the same decorative and romantic approach. The Christian faith was for him, as unfortunately for his sponsor, just one facet of the «Russian soul. » Most members of the Russian intelligentsia of that time were interested in religion and spirituality only as a delicate cultural pleasure: for them it was merely a beautiful myth that pleasantly tickled their imagination, but it was not life. Let us quote an excerpt from Princess Tenisheva's Memoirs. These lines were inspired by a Vespers service celebrated at her home for her family and guests.

"I wanted to celebrate the feast of my guardian angel in a Christian manner, in the old way. It was like a breath on my soul, reminding me of the forgotten days of this ancient time in the life of the manor house, when our ancestors accompanied every family celebration with prayer ... The audience was also in a good mood, not to mention the servants, who are always softened by these forgotten but so moving habits."[1]

One cannot be clearer. Any anti-religious pamphleteer could have signed this naive blasphemy. For our sponsor, a liturgical celebration is nothing more than a curious forgotten habit that in bygone years added luster to family celebrations, and remains so moving for domestics. And here now a totally different page of her Memoirs. She decides to do something good for these little people: to have a church built for them, while improving their taste. What enthusiasm, what confidence in her beneficial mission! She tells how she came to knew Roerich and under what circumstances she entrusted him with the decoration of the church of Talashkino.

"As soon as I spoke, he seized my words.[2] And this word, it was 'A church ...!' "If the Lord allows it, it is with him only that I will finish it. This is a man who lives in the Spirit, who has received the spark of the Lord, and it is through him that the divine truth will come. The building of the church will be completed through the power of the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit is the strength of the spiritual joy of God, binding and enveloping the Cosmos with its mysterious power. What a task for an artist! What scope for the imagination! How his creativity will be able to apply itself to the church of the Spirit! We understood each other! Nikolai Konstantinovich fell in love with my idea, he understood the Holy Spirit. Amen. Right along the road from Moscow to Talashkino our friendly dialogue continued, elevating our thoughts and our plans to join Infinity. Oh, these holy minutes, full of grace...!«[3]

Anyone with any familiarity with Orthodox spirituality recognizes the symptoms of this kind of hysteria. The state of the soul of our princess could simply be described as prelest and at an already well advanced stage! Prelest is the Russian term which designates spiritual delusion, a state considered more dangerous than the worst sin in Orthodox ascetical theology. And it is in this spirit that the church construction project was had been conceived and the frescoes were sketched out and implemented!

The princess describes in detail the evolution of her ideas, the sleepless nights spent on her project, her efforts to express her nostalgic ideas about «forgotten things» and the emotions of a bygone era. Neither she nor Roerich doubted at any stage the spiritual quality of their work. They sought no advice, whether from priest, professional iconographer, or theologian. This church belonged to them and them only. Every time the Princess speaks of it, it is: «my church, my temple.» And Roerich for this commission gives free rein to his creative desire to express the national art nouveau.

In this context it was primarily the interior poverty and impiety of this approach that outraged the representatives of the Church hierarchy. Whereupon they unsurprisingly refused to recognize and bless the decoration of the church of Talashkino. The lack of spiritual canonicity of Roerich's works was neither masked nor compensated by its having respected the iconographic canon or being in the Byzantine style.

Vrubel, by contrast, had not compensated or hidden anything. The Academic style does not lend itself to what his intentions. His goal was the expressiveness of a realistic image, and the image of the Mother of God is indeed highly expressive. But how do we sense these parched lips, this childish face with pleading, black-outlined eyes, and these thin nervous fingers? The dominant impressions are of naive sensuality, abandonment to sin, of submission to the passions, but also this constant nervousness that so often marks Vrubel’s secular works, this painful fracture of refined natures, destined for the sublime, but compromised by their turning away from the destiny intended for them, and repeated again and again in portraits, paintings, and decorative panels. By attributing to the Mother of God the traits that attracted and fascinated him in women, Vrubel committed a serious spiritual error. But in addition, as the documents of the time tell us, he had placed himself in a highly delicate situation. Falling in love with the young wife of his patron A.V. Prakhov, in whose house he was living, the brilliant young bachelor courted the young woman, all of which ended in a violent quarrel between the artist and his patron.

In the icon rejected by the Church we find the charming, childlike features of Madame Prakhova who had served as a model. It was not, however, the fact of painting from a live model [4] which prevented the icon being accepted, but rather the sentiments transferred from the model into the sacred image - nervousness, anxiety, passionate excitation - deemed by Vrubel to represent real spirituality, but very far from the vision of the Church. These feelings, having become the leitmotif of his painting, are expressed in his work by mythological images, including the figure of Vrubel's main hero, the Devil. These morbid and dangerous spiritual games ended in mental illness, blindness, and an early death. It is rare to see someone punished in his lifetime, and so visibly, for his apostasy.

Unlike Vrubel, Roerich lived a long time, enjoying recognition and fame. His renunciation of the truth of the Church subsequently turned into active opposition, with Nicolai and his wife Helena becoming widely known occultists in the wake of the famous theosophist Helena Blavatsky. In his subsequent paintings and panels, mystical landscapes of Mongolia, India and Tibet replace the villages of Old Russia. They express a very special spirituality, aggressive, devoid of humanity, and deprived of God, the same spirituality that had denatured the frescoes and mosaics of Talashkino and had left the church unconsecrated.

These two examples are important for understanding the specificity of the spiritual canon, because the two creators were first-rate artists, with their own styles perfectly expressing their very personal spirituality, along with the apostasy characteristic of their mental structures. The quality of their artistic technique made them quite capable of accurately expressing what they felt and thought they knew. It is visible that in their eyes the Lord, his Mother and the saints are not full of goodness, peace, and joy. The depiction of them radiate neither love, nor mercy, nor consolation. If the Academic painter Vrubel shows them at least as beautiful and intelligent, the Byzantinist Roerich makes them also disturbing, stupid and ugly.

A certain «theology of the icon» ignores this notion of «psychic» (= of the soul) discernment, believing as it does that both icons and iconographers float in the field of pure spirit. It seems to us, however, vitally important to assess the spiritual value of any icon, in particular any icon which is going to be critically involved, through prayer in front of it, in a person’s soul life. According to Orthodox ascetic theology it is through our soul that we gain access the invisible world, that ‘a well of living water springs up to eternal life’ (John 4.14), that the fruits of the spirit - love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trust, gentleness, self-control (Gal. 5.22) - begin to exhibit themselves, and that we begin to «see God» (Matt. 5.8). The depth of this access is critically dependent on the purity, not only of our own soul, but also of any other person playing an intimate intermediary role in this access (an artist painting an icon a person prays in front of, a priest hearing the same person’s confession etc.). What happens (or should happen) when an icon is presented to the priest to bless it, is a discernment of the ability of the icon to serve as in this intermediate role, and in particular of any feature that could block or distort this communication. We would insist that such discernment is not only permissible, but is spiritually essential.

As long as we remain in the world here below, we cannot judge the invisible world other than through the soul (the psyche). Saint Paul, in his Epistles, teaches us the «psychic» terminology as a discipline giving prominent place to the Holy Spirit and by which we avoid the pitfalls:

For the time is coming when people will not put up with sound doctrine, but having itching ears, they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own desires, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander away to myths. (2 Timothy 4: 3-4)

We sinners have a tendency to follow the wrong roads:

«Delighting in humble devotional practices, in worship of angels, this one gives full attention to his visions, puffed up in vain pride by his fleshly mind. (Colossians 2: 18)

To muzzle this excess, the apostle keeps coming back to «psychic» benchmarks in the field of the spirit:

But here is the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, trust, gentleness, self-control; against such things there is no law. (Galatians 5. 22-23)

For you were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Walk as children of light. And the fruit of light is called goodness, justice, truth. Learn what is pleasing to the Lord. Do not associate you with the unfruitful works of darkness; but instead expose them. (Ephesians 5, 8-11)

Finally, brethren, all that is true, noble, just, pure, whatever is lovely, honorable, whatever is called virtue and deserves praise; this is what you should concern yourselves with. (Philippians 4, 8)

We ask God that you will have full knowledge of his will in all wisdom and spiritual understanding; for you to lead a life worthy of the Lord, seeking his total approval. By everything good that you do, you will bear fruit and make progress through the true knowledge of God; you will be strengthened in every respect with the force of his glory and led in this way to perseverance and longsuffering with joy.

(Colossians 1. 9-11)

For Orthodox Christians, holiness and spirituality are not abstract, but concrete and positive notions, recognizable by certain qualities and moods. The liturgical texts and prayers of the Orthodox Church abound in psychic terms. This means that we can also require that the icon provide a correct, canonical image of God, in the same «soul» terms. If the character depicted on the icon, even if crowned with a halo and provided with suitable inscriptions, looks nasty, aggressive, powerless, ugly or stupid, the spiritual canon of the Church regarding the ideal representation of God is brutally violated, just as seriously as the iconographic canon would have been if that character had given a blessing with the left hand or was wearing a tuxedo.

The theology of the icon needs to try to understand how the images of the world and of man, passing through the filter of the artist's soul, and expressed with care and respect by his or her hand, are transformed into expressions of spirituality. It is precisely this phenomenon, at once the most subtle and the more specific, that a true theology of the icon ought to treat of, because it touches on the ontology of the icon, on the miracle of the incarnation of the psychic which leads to the spiritual level, an incarnation brought about by material things as simple as a board and a little paint. How do we define why sometimes this expression of spirituality at times takes us to heaven, and at other times hurls us into hell? What has the artist done with his object? How has he transfigured it? No theology has to date properly examined this field.

It is time to lay the roots of a serious theology of art in general and of the art of the icon in particular. This science has to be founded by the combined efforts of Christian anthropologists, Christian theorists of the fine arts, and Christian theologians. The absence of this science has been and continues to be very harmful not only for sacred art, but for art in general, because of course all art is spiritual, and all artistic creation is a spiritual activity. Vladimir Weidle, an eminent thinker of the first Russian emigration, called art "the mother tongue of religion«[5], reminding us with finesse and precision that the true specificity of art is the realm of the invisible, the field of deep feelings that are expressed in artistic images, feelings that no verbal mode of expression is able to express.

At the same time, spiritual activity and asceticism are considered in the tradition of the Church not as a science or as a sport but rather as an art. The Philokalia (that is to say Love of Beauty), a classic collection of works on Orthodox asceticism, confirms to us that Beauty is well recognized as a spiritual category. In the icon, we come to the knowledge of the Spirit through visible beauty, but this beauty (the beauty of a concrete art style and the beauty of a concrete person represented) is itself generated by the spirituality of the artist which it reflects. This artist has developed his individual style in the framework of the school and tradition to which he belongs, also it is he that lends to the sum a facial features a particular expressivity, conceived in advance and rendered with great effort. And it is in doing this that the artist’s mission towards the Church and the world lies, today and in the future.

At this stage we must take care to avoid vulgar simplification. While an artist's spiritual physiognomy is not fixed «automatically» in his work as a photographic plate (and an amateur who has not mastered his art cannot possibly fix his spiritual physiognomy, simply because he will be unable to fix anything), a gifted artist, carefully trained in a specialized school, will acquire the ability, not only to paint the visible universe, but also to express, almost despite himself, the invisible universe, including his own spiritual physiognomy. Through his training in a specialized school, the artist-in-becoming will benefit from the spiritual acquis, that is the accumulated experience and knowledge, of the school, through imitating the art and, with it; the spirit of his teachers. This is how the mechanism of the blossoming out and development of the great historical styles of the past took place.

So, how should an iconographer be trained? How does one receive the spiritual tradition via the artistic tradition? That is the subject of the next chapter.

[1] Princess M.K. Tenisheva, Впечатления моей жизни. Leningrad, 1991, p 126.**

[2] It comes as not surprise that Roerich had jumped at the opportunity, since his commercial genius was on a par with his artistic talents ...!

[3] Princess M.K. Tenisheva, op. cit. p. 250

[4] Other academic painters also painted from live models: Nyestierov, Vasnyetsov ... and their works were accepted by the Church.

[5] V. Weidle, Искусство как язык религии, in Le Messager (A.C.E.R.) n° 50, Paris-New York, 1958, pp. 2-10