Lord Byron & the Byronic Hero in Sense & Sensibility

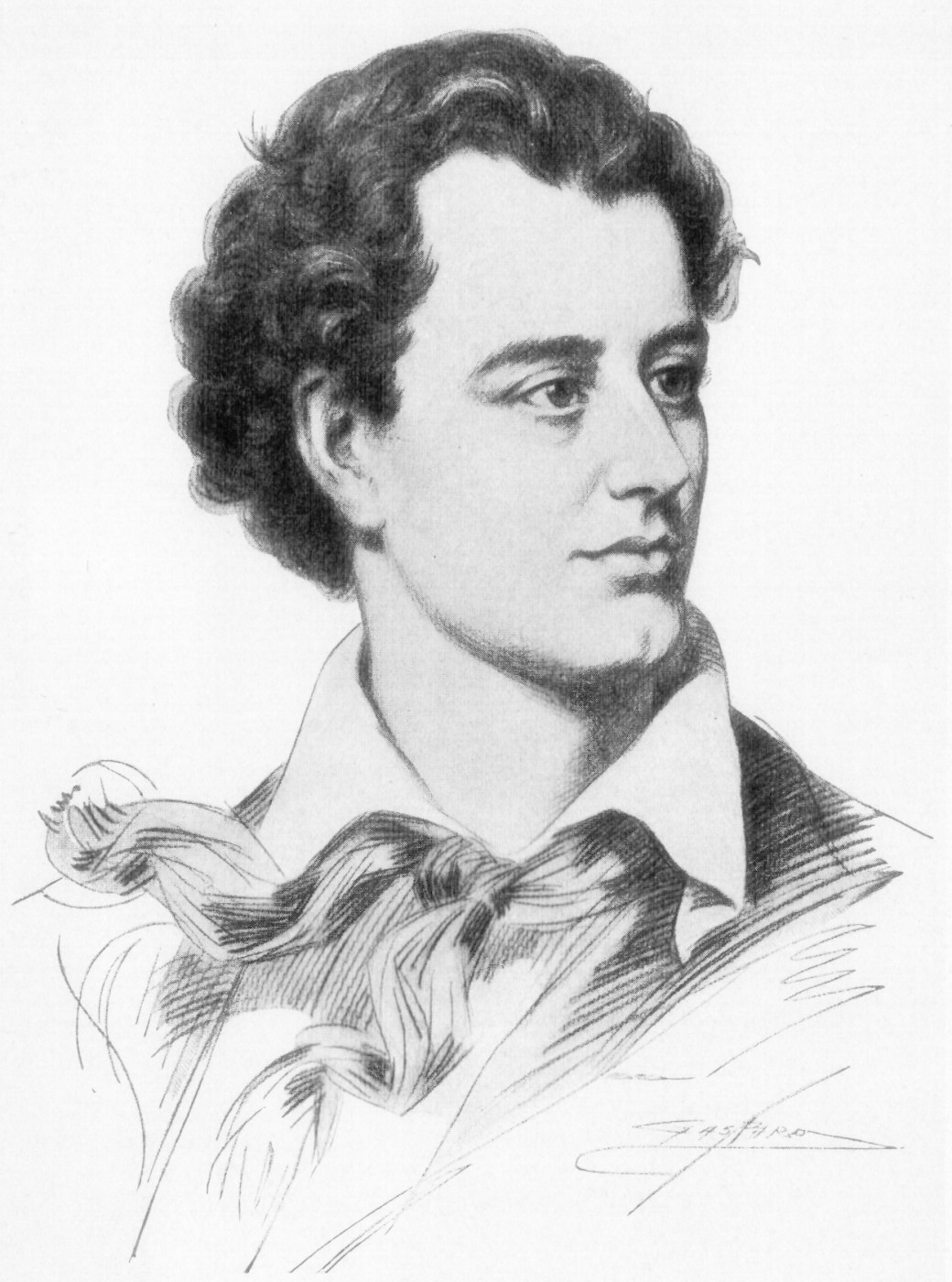

Laurel Ann blogged this morning about Sense & Sensibility's Mr. Willoughby as a Byronic hero. During part one of S&S08 I made the remark to Molly that it is peculiar and appropriate for Mr. W. to ask Marianne whether she was familiar with Lord Byron - she knew the name, by the way, but hadn't read any works. It sort of fascinates me he's mentioned in the present because, as the crowned Romantic--capital R--prince, the familiar seems somehow sacrilegious. This is a little like saying that Beowulf was effeminate (which I actually said in my twenty-ought-six writeup "Gendering Beowulf") and warrants a double-take. After all, Lord B.'s an Olympian.

But Lord B. was Jane Austen's contemporary--and he was mad, bad, and dangerous to know - as you know--in literary adolescence when Mr. W. quotes "She Walks in Beauty" from memory (he's one of those) to woo that sixteen-year-old girl. This was in 1811; one-hundred-ninety-seven years later I suspect Marianne would wear a piercing in her lip and her bangs dyed black. White rebel suburban teens get it bad for Byron, you know. And it makes sense that Marianne was easy prey to this: her family might have lost the mansion with its entailment, but their [seashore] cottage was goodly sized, and no one was by any means going hungry. Sheltered, young, fatherless, and strained by the restrained example of her sister Elinor, what she knew about adventure was--like Austen--through Tom Jones or Lovelace: Romanticized, romanticized, and Northanger.

In terms of Romantic sensibility, if Wordsworth et al. exemplified the dewey-eyed appreciation of flora and the smells of morning, then Byron was at awe in the dark. This Yin-and-Yang is a pretty good way to think about it, because while there is probably some fay-like virtue of the pastoral, the dangerous side to a connection with nature is the threat of becoming bestial. Remember that before there was a royal Lord Byron there was a Mad Jack.

Tall-dark-and-handsome Mr. Willoughby--refer to my last S&S08 thread about the problem with unrestrained passion--then strikingly appropriately invokes Byron, showing also that his knowledge of a thing like poetry isn't confined to old libraries ("to be admired" he says about Alexaner Pope, then shuts the book for good), but he is immersed in the contemporary elitist literary snobbery.

He is proud and well-educated, runs with the moral-fringe of society (Byron/Shelley-admirers), and thus dangerous to the rigid status quo of Regency society - the society that filled the ranks of the clergy (second sons, who didn't inherit an estate, went to God [third sons went to War]); it's worth noting, then, that Byron/Shelley etc. are, considered as a subgroup of the Romantics, "Satanic:" not because they worshipped the Devil, but because they were so far left of the moral right. William Blake was the big daddy (re: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).

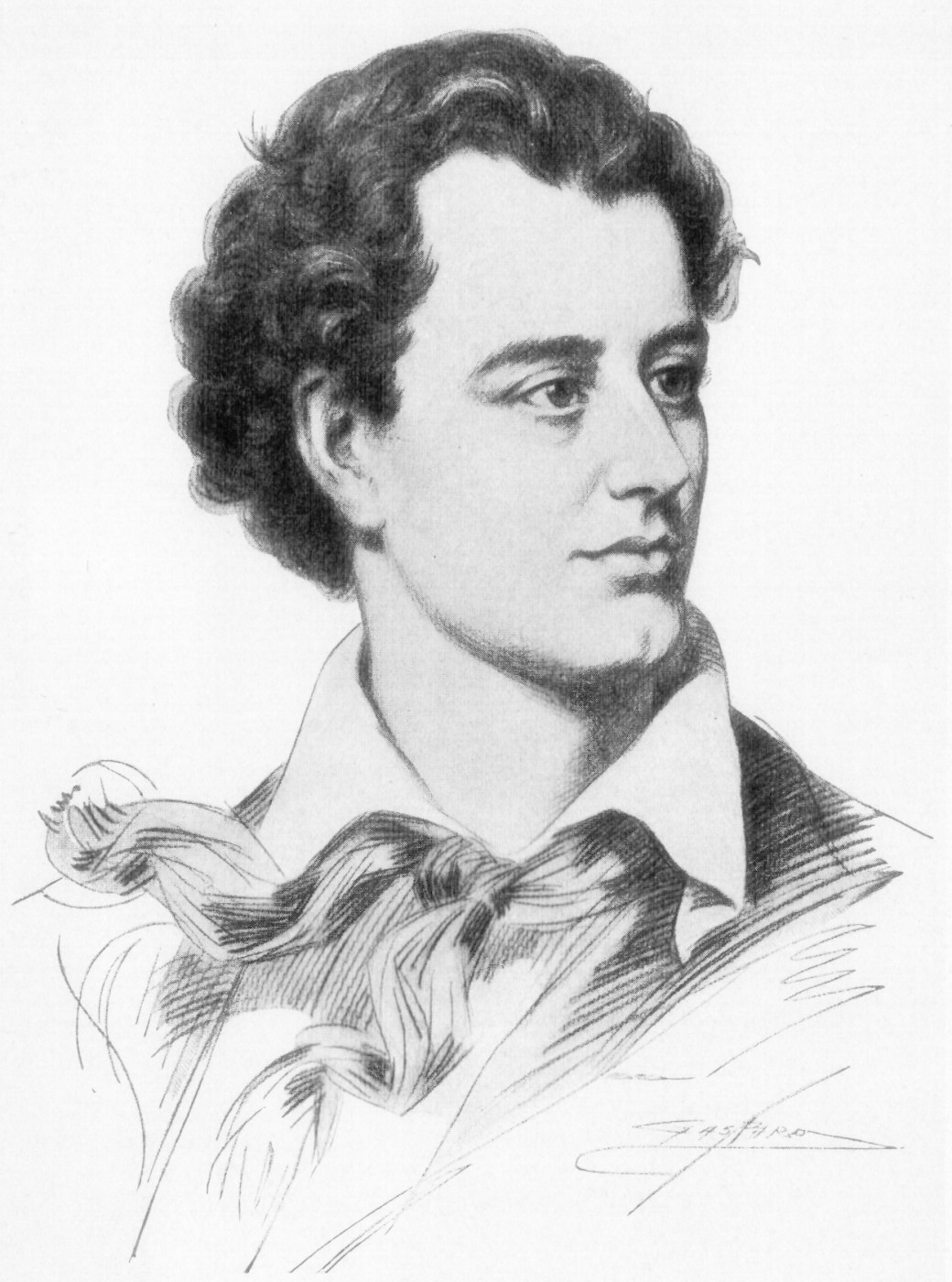

But Lord B. was Jane Austen's contemporary--and he was mad, bad, and dangerous to know - as you know--in literary adolescence when Mr. W. quotes "She Walks in Beauty" from memory (he's one of those) to woo that sixteen-year-old girl. This was in 1811; one-hundred-ninety-seven years later I suspect Marianne would wear a piercing in her lip and her bangs dyed black. White rebel suburban teens get it bad for Byron, you know. And it makes sense that Marianne was easy prey to this: her family might have lost the mansion with its entailment, but their [seashore] cottage was goodly sized, and no one was by any means going hungry. Sheltered, young, fatherless, and strained by the restrained example of her sister Elinor, what she knew about adventure was--like Austen--through Tom Jones or Lovelace: Romanticized, romanticized, and Northanger.

In terms of Romantic sensibility, if Wordsworth et al. exemplified the dewey-eyed appreciation of flora and the smells of morning, then Byron was at awe in the dark. This Yin-and-Yang is a pretty good way to think about it, because while there is probably some fay-like virtue of the pastoral, the dangerous side to a connection with nature is the threat of becoming bestial. Remember that before there was a royal Lord Byron there was a Mad Jack.

Tall-dark-and-handsome Mr. Willoughby--refer to my last S&S08 thread about the problem with unrestrained passion--then strikingly appropriately invokes Byron, showing also that his knowledge of a thing like poetry isn't confined to old libraries ("to be admired" he says about Alexaner Pope, then shuts the book for good), but he is immersed in the contemporary elitist literary snobbery.

He is proud and well-educated, runs with the moral-fringe of society (Byron/Shelley-admirers), and thus dangerous to the rigid status quo of Regency society - the society that filled the ranks of the clergy (second sons, who didn't inherit an estate, went to God [third sons went to War]); it's worth noting, then, that Byron/Shelley etc. are, considered as a subgroup of the Romantics, "Satanic:" not because they worshipped the Devil, but because they were so far left of the moral right. William Blake was the big daddy (re: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).