Almanac When I Damn Well Feel Like It-The Best Real Estate Deal in History?

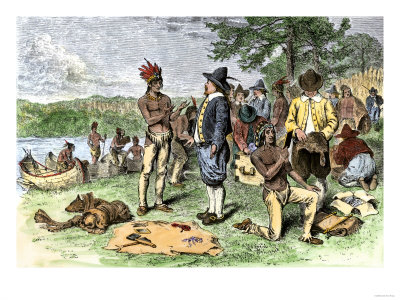

A fanciful 19th Century engraving of the purchase of Manhattan Island.

On this day in 1626 what has been called the greatest real estate deal in history went down. But the real winner in the deal is not the one you have been told about.

Due to a simplistic account in a 19th Century popular reader, almost any American will tell you that Manhattan Island was bought by the Dutch from local Indians for “$24 in beads and trinkets.” Those with especially acute memories might recall it was Peter Minuit, Governor of the North American colony by the Dutch West Indies Company was the sharpie who allegedly hoodwinked the natives with his paltry offering.

There are several things wrong with this version. First and foremost is that the trade goods Minuit offered were not the trade trifles mentioned, but a selection of metal tools and implements including axe heads, knives, awls, needles, cast iron kettles, as well as cloth. They were valued by Minuit at 60 silver guilders a significant sum. Depending on who is doing the reckoning and how inflation over nearly four centuries is figured, that would be worth more than $1000 in today’s cash. Or in silver value by weight it would be about $68 at today’s quoted prices.

But as one historian points out, the value of the items to the natives was probably much more than the actual monetary value. Most of these items had been virtually unobtainable, although a few may have found their way ashore from other European ships or have been traded down from New England or far away New France. A historian described it as a significant “high-end technology transfer, handing over equipment of enormous usefulness

But it was the natives Minuit dealt with who may have been the real sharpies. He assumed he was doing business with the Lenape, a powerful and extensive tribe that held sway over what is now the Delaware Valley including much of modern New Jersey and over the area around the mouth of the Hudson River including Manhattan and much of Long Island. They were a sedentary people engaged in extensive agriculture and both costal and inland fishery, including the harvesting of oysters. Relatively large villages relocated within the range every year or so, returning to previous sites when the land rejuvenated itself.

Evidently the local Lenape, however, were not using Manhattan at the time the Dutch arrived. Instead, they made sort of a sub-lease agreement with the much smaller Canarsie tribe who shared some of Long Island with them and a dozen other small bands. It was likely Canarsie harvesting oysters and gardening with who Minuit negotiated. Hardly believing their good fortune, they gladly sold the Dutch what didn’t belong to them and retreated to Long Island with what they must have considered a fortune.

A previous governor had established Fort Amsterdam on the southern tip of the island the year before. Minuit felt secure enough in his sale to begin settlement of a new colonial capital Nieuw-Amsterdam. Eventually the Lanape, who became the chief partners of the new colony in the fur trade, complained about the Dutch squating on their land and another purchase had to be arranged. The exact price paid in this second deal is lost to history, but the Lenape likely did pretty well in trade goods themselves.

The fates of all parties to the deal were unhappy.

In 1631 Minuit was fired by the Dutch West India company for failing to meet expectations for the fur trade and was accused of skiming accounts for his own benefit. Enraged, he returned to Europe and offered himself to the Swedes, an ascendent European power eager to get into North American colinization. In 1638 he returned as governor general of New Sweden and established Fort Christiana new modern day Wilmington, Delaware. He was killed later the same year on a return voyage to recuit more settlers. He sailed via the Caribean to pick up a load of tobacco to make the journey profitable for the company and perished in a huricane near the island of St. Christopher. His colony lasted a dozen more years until a later Dutch governor, Peter Stuyvesant conquered in 1655.

The Canarsie, one of thirteen small tribes on Long Island, allied themselves with the much more powerful Mohawks from the mainland for protection. They lived in relative harmony with the Dutch until a later governor, William Kieft, launched a war on local tribes. A massacre of the village of Pavonia united all of the tribes in a general uprising in 1643. The ensuing war was devastating to both settlers and the tribes. Peter Stuyvesant eventually negotiated a peace. Many Canarsie converted to Christianity during the period of peace and continued to farm and fish in the area.

The Dutch persuaded the 13 tribes of Long Island not to pay tribute to their traditional protectors, the Mohawks. In 1655 a large Mohawk war party invaded Long Island and massacred most of the local tribal residents.

A remnant of the Canarsie later sold most of their remaining land to the British, after they seized New Amsterdam. Small numbers continued to live and farm in rural Brooklyn into the 19th Century. A unit of Canarsie volunteers served the Civil War. Eventually descendents of the tribe became absorbed by the white community and the tribe disappeared into the mist of history.

The much larger Lenape at least persist as a people. Their culture was much disrupted by the arrival of the Dutch, Swedes, and the English in Pennsylvania. In order to obtain much desired trade goods, they abandoned much of their traditional agricultural and fishery based economy to pursue the fur trade. This took them deep into hostile territory dominated by the Mohawk and other Iroquoian people. By the late 18th Century pressure from the Iroquois and expanding European settlement forced most major bands to re-settle west of the Allegany Mountains in what is now western Pennsylvania and along the Ohio River. Remnant bands in the east were mostly absorbed by other tribes or by neighboring white settlements.

After the signing of the Treaty of Easton in 1758, most the Lenape were forced to move west out of their lands in Delaware, New Jersey, eastern New York, and eastern Pennsylvania into what is today known as Ohio. A large number of Lenape were converted by the Moravians, a German pietistic sect that practiced pacifism. These “praying Indians” settled along the Ohio River with their missionaries west of Ft. Pitt.

In the French and Indian Wars more warlike bands allied themselves with the French and were present at the siege of Ft. Pitt.

During the American Revolution bands of the tribe by then generally known as the Delaware, split allegiances between the British and the colonists. Several large bands relocated to the Sandusky to be closer to the British stronghold of Ft. Detroit. Others scouted for the Americans, or in the case of the Praying Indians tried to remain neutral. Coshocton was the main town of the Delaware friendly to the colonists. They hoped to form an all Indian state within the infant republic. But after their chief, White Eyes was killed, probably by American militiamen, many of the warriors from Coshocton joined their kinsmen with the British.

American Colonel Daniel Brodhead led an expedition out of Fort Pitt and in 1781 destroyed Coshocton. Surviving residents fled to the north to the British. The next year the peaceful Moravian missionary village of Gnadenhutten was attacked by Pennsylvania militia. At least 96 men, women and children were massacred.

Various Delaware bands were caught up in the continuing fierce warfare along the Ohio frontier after the Revolution. Some took up arms again with the British in the War of 1812. After the capture of Ft. Detroit in that war, northern Delaware bands, including some of the Moravians relocated to what is now western Ontario.

Most of the remaining American Delaware ceded their lands in Ohio in the Treaty of St. Mary’s in 1814. Bands took up lands in Indiana and Missouri. . In 1829 yet another treaty, the Treaty of James Fork pushed the tribe yet further west. In exchange for the Indiana and Missouri lands they received grants in Kansas.

The Delaware became active as guides and trappers in the trans-Mississippi west and frequently served as scouts for the Army. They were prominent in the Seminole Wars and were among those with John Charles Frèmont when he entered California during the Mexican War. Later they would be guides for emigrant trains to the west.

Despite loyal service the Delaware were again pushed from their lands. Most relocated to Indian Territory by 1860. They were forced to buy lands from the Cherokee. In 1979 The Bureau of Indian Affairs ceased to recognize the Oklahoma Delaware as a separate tribe and began to count them as Cherokee. That decision was overturned in 1996. A challenge by the Cherokee to the re-instatement caused a see-sawing legal battle with the tribe stripped of recognition again and then having it restored. As of 2009 they have had tribal status and the same year reorganized under the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act with a tribal government of its own.

Small bands of Lenape or Delaware are scattered from New Jersey to Wisconsin but have no formal recognition. In Ontario decedents of the Lenape of Ohio still live on four reservations.