Almanac When I Damn Well Feel Like It-First Acquitted “By Reason of Insanity"

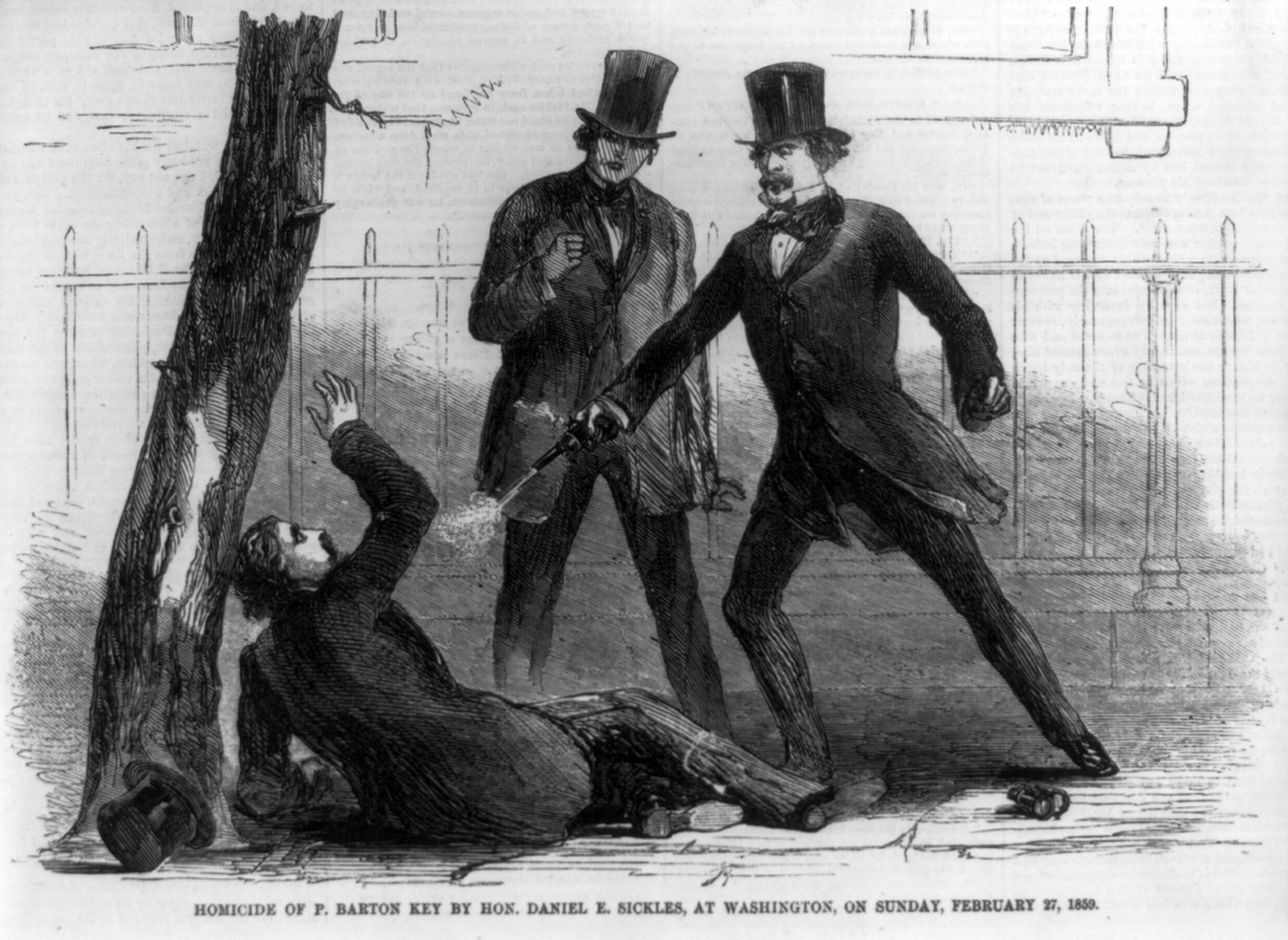

By any measure, Daniel Sickles was a colorful character. He was in his second term as a Democratic Congressman from New York City when he hunted down and shot in cold blood the District Attorney of the District of Columbia on February 27, 1859. Sickles fired a second shot as the man laid on the ground pleading for his life. The victim, Philip Barton Key, was the son of Francis Scott Key, composer of the Star Spangled Banner and the son in law of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney.

Now for most folks, this kind of thing can lead to real trouble. Maybe even tarnish a career. Not Dan Sickles. He seemed to thrive on the surrounding hubbub.

Born in New York in 1809, Sickles was the son of a patent lawyer and small time politician. After trying his hand as a printer, he attended the University of the City of New York. Following his father, he threw his lot in with the rising Tammany political organization. By 1843 he was serving in the state Assembly. He was also reading law in Benjamin Butler politically powerful firm and was admitted to the bar in 1846.

Sickles rose even as he garnered a reputation as a hard drinking ladies man and a pugnacious political scrapper. He was censured by the Assembly for bringing a known prostitute to the chamber. Later, when appointed Secretary of the American Legation in London by President Franklin Pierce, he arranged to introduce the same woman, Fanny White, to Queen Victoria under the last name of a political opponent back home. That’s the kind of guy Sickles was.

That was in 1853. A year earlier Sickles had married a 15 year old beauty, Teresa Bagioli, the charming daughter of a well known Italian music teacher and rumored to have been the “natural child” of another musician, the son of Lorenzo da Ponte, the librettist for Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and other operas. Sensitive to charges that he “robbed the cradle” Sickles began lying about his age, absurdly claiming to be born in 1825. This fooled no one but a few sloppy historians.

Despite his own continued affairs and dalliance, Sickles was extremely jealous of his child bride.

After a turn in the New York Senate, Sickles was elected to Congress in 1856. Charming and accomplished the couple became leaders in Capital city society. But Sickles continued his extra-marital affairs. Lonely, Teresa solace found with Key, a frequent visit to social occasions in their home. Romance bloomed.

After receiving an anonymous letter exposing the dalliance, Sickles confronted his wife who, after initial denials, wrote out an extraordinary detailed confession of the affair that included dates of assignations and the fact that key rented a house in a mixed race neighborhood for their afternoon rendezvous. On February 27, 1859 Sickles said he saw Key outside his home signaling his wife with a waved handkerchief, he armed himself with multiple pistols and pursued Key. He caught up with him in Lafayette Park right across the park from the White House. After wounding the man, Sickles aimed his second shot at Key’s groin as he lay on the ground.

Sickles calmly turned himself into Attorney General. He was allowed to return home in the company of a constable where he took his wife’s wedding ring. In jail he was allowed to keep a “personal weapon” and received a string of admiring visitors in the jailer’s private apartment.

Sickles masterfully manipulated the frantic press coverage of the event. Far from protecting his wife’s reputation, he let it be known that she had been involved in an adulterous affair. Sympathy was almost unanimously with the cuckolded husband out to avenge a depredation on the “sanctity of the home.” He secured the top lawyers in the city, including Edwin Stanton, a Republican and future Secretary of War.

The trial began on April 4. Defense attorney John Graham launched into a three day opening statement which simultaneously painted Key as the real villain, was flooded with Biblical allusions, and argued that Sickles was so consumed in justifiable rage that he was deprived of reason. The prosecution presented a straight forward case based on testimony of numerous eyewitnesses. They never bought up any of Sickles’s own numerous affairs, many with married ladies.

Although the judge ruled the written admission of Mrs. Sickles inadmissible, it was leaked to the press and published in full during the trial.

On April 26 the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. The first plea of temporary insanity in an American court had succeeded.

After the trial Sickle “withdrew” from public life for a few months, but did not resign his seat in Congress. Eventually he resumed his duties. The sharpest criticism he received in the press was not for the murder, but for reconciling with his adulterous wife.

Despite his Democratic loyalties, Sickles personally raised four regiments in New York State when the Civil War broke out. He was commissioned Colonel of one of them. Political opponents blocked the appointment, but allies, probably Edwin Stanton himself, intervened and he was restored to his command. Sickles rose rapidly as a “political general.” He served with some distinction in several battles.

At Chancellorsville, in command of the Army of the Potomac’s III Corps, Sickles clashed with his close friend and sponsor in the army Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. He wanted to pursue a large force in his sector, which turned out to be Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate corps which was making a flanking maneuver that would take the army by surprise. He also objected to later orders that caused him to evacuate a strong defensive position.

That these judgments proved, in retrospect, entirely correct, only confirmed Sickles’s determination to follow his own instincts despite order on the next opportunity. That opportunity came on July 2, day two at Gettysburg.

Ordered by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade to use his III Corps to anchor the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, Sickles instead advanced his men well ahead the line to a position in the Peach Orchard. The exposed salient was open to attack on three sides. III was effectively destroyed as a fighting force by troops under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. In the thick of the fight, Sickles was struck by a cannon ball which shattered his right leg. He had to be carried from the field. Surgeons amputated his leg, which he preserved in a small casket. Later, he donated the leg to the Army Medical Museum in Washington which put it on display. Sickles would visit the leg annually on July 2 for the rest of his life. The bone can still be seen in the successor institution, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Despite his injuries and wide spread criticism of his disastrous decision at Gettysburg, Sickles remained in the service and indeed received a commission in the Regular Army although he never again got a combat command.

He served in the Reconstruction South in several high command positions before retiring from the Army in 1867. The same year his wife died.

In 1869 Sickles was named Minister to Spain in that capacity he urged war with Spain over the seizure of the Virginius, a ship under the American flag caught running guns to Cuban rebels, when the Spanish executed the captain and several other Americans as well as Cuban found on board. Despite this he was popular at court. And he continued to pursue the ladies. The deposed Queen Isabella II was said to be among his conquests.

In 1871 Sickles married Senorita Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh, a Spanish Councilor of State. He would father two more children with his second wife.

Back in the United Sates after concluding his foreign service in 1874, Sickles became head of New York Monuments Commission where he raised funds for a monument to New York troops at Gettysburg. He later played a key role in preserving the battlefield for the public. He also, apparently, embezzled about $27,000 of money raised by the Commission for the Gettysburg monument. The monument was eventually erected, but without a planned bust of Sickles himself, leaving him the only senior commander on either side of that battle to be honored with a statue there.

He served in a succession of posts, including on President of the New York Civil Service Commission and as Sheriff of New York. In 1893 he was returned to another term in Congress. While there he renewed his campaign for recognition of his Civil War service. The charm campaign worked. In 1897 after leaving Congress for the last time, Sickles was awarded the Medal of Honor for his courage under fire at Gettysburg.

Sickles lived quietly, or as quietly as any old rogue can, in retirement in New York until his death in 1914 at the age of 93. His flag draped coffin was loaded on a caisson and escorted to funeral services at St. Patrick Cathedral with full military honors. He was interned at Arlington National Cemetery, where you can view his grave after seeing his leg in the medical museum if you want to make a day of it.