Today's Almanac--September 5, 2010

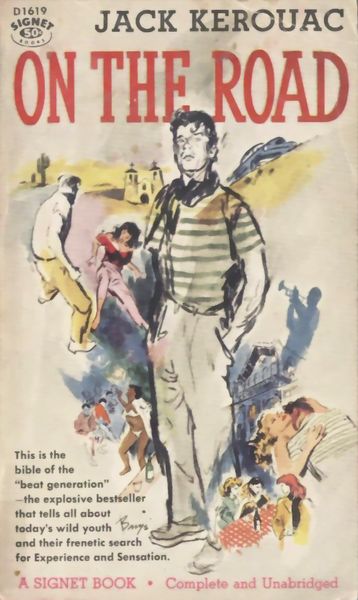

The cover of the cheap mass market paperback edition issued by Signet a year after the Viking edition of On the Road. This is the edition, which slipped easily into the back pocket of a pair of jeans, reached would-be Beats as far away as Cheyenne, Wyoming.

On September 5, 1957 Viking Press published a book that may be one of the most significant American cultural artifacts of the 20th Century-On the Road by Jack Kerouac. It has been compared to Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass-a fresh look at America though entirely self-conscious eyes and presented in a revolutionary literary form. It was hailed as “the Bible of the Beat Generation.” Truman Capote haughtily dismissed it-“That's not writing, that's typing.”

The book is thinly disguised autobiography. The original manuscript, the legendary scroll-120 feet of thin tracing paper taped together and fed through Kerouac’s portable manual typewriter as he wrote in a frenzy of creativity in a few weeks of April 1951-contained the real names of the characters and a lot of detail-much of it sexual, that was left out of the published version for fear of obscenity laws. The book described the bohemian circle of friends he had in New York, especially young Alan Ginsberg, encountering the outlaw/saint/hero with whom he embarked on a series of cross country trips, separating and reuniting at intervals as the writer becomes increasingly alienated from the free spirited wander. The trips began in 1947 and continued to early 1950. All the while Kerouac kept a series of detailed notebook on which based the manuscript.

Over the next six years Kerouac revised the text of the scroll substantially, including changing the names of the characters transforming a memoir into a novel. He became Sal Paradise, Cassady Dean Moriarty, and Ginsberg Carlo Marx. So although the original manuscript reflected Kerouac’s passion for “spontaneous writing,” it had roots in the notebooks, from which large passages were lifted nearly intact, and was subject to considerable revision and editing.

Jack Kerouac was born to French Canadian parents in the old mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts on March 12, 1922. The working class family spoke Joual, a rough dialect of Québécois Creole, at home and Ti Jean (Little John), as he was called, spoke no English until he was 6. Later some of Kerouac’s first writing was done in Joual.

Ti Jean was very close to his mother, Gabrielle-Ange, a devout Catholic who imbued him in the faith. Catholicism, particular its mystical side, would inform Kerouac’s writings even during his most intensely Buddhist period. In his last years, living with and caring for his ill and aged mother, he returned to regular Catholic observance.

Kerouac first encountered New York on a trip to the city with his father Leo in 1935 at the age of 15 which would become the inspirations for his unpublished Joual novella Sur le Chemin (On the road), later translated as Old bull in the Bowery. His connection to the city was visceral from the beginning. When his skills as a high school football player earned him scholarship offers from Boston College, Notre Dame, and other prestigious schools, he opted for Columbia University because it was in the city.

Both his football and academic careers were cut short when he broke his leg freshman year and when his instinctive resistance to authority brought him into conflict with his coach, who kept him on the bench. Kerouac dropped out after a year and drifted along, although he took some classes at the New School. While living on the West side he encountered some of the circle of Bohemians he would make famous Ginsberg, John Clellon Holmes, Herbert Huncke, and William S. Burroughs.

In 1942 Kerouac joined the Merchant Marine and thereafter often referred to himself as a sailor, although his career was brief. The following year he enlisted in the Navy but went on sick call after little more than a week and was soon honorably discharged because of disability with a diagnosis of schizoid personality.

Returning to New York, he drifted from job to job and settled into a life revolving around his friends. Chief among them was Lucien Carr, the brilliant and handsome scion of an influential St. Louis who introduced him to Ginsberg, Burroughs-another wealthy St. Louis native several years older than the rest of the group-and others. Kerouac and Carr hoped to ship out to France together on a freighter and then somehow walk across the war torn country disguised as a French peasant (Kerouac) and a deaf mute (Carr) to be in Paris when the city was liberated by the allies. They got as far as spending one night on a ship before being thrown off of the crew for some reason before it failed.

Carr had been stalked for years by a former teacher and friend of Burroughs, David Kammerer. The infatuated man quit his job and moved to New York in an attempt to start a relationship. Carr alternately ignored him or tolerated his presence on the fringe of their social circle. One night after drinking Kammerer allegedly assaulted Carr in Central Park after the younger man again rebuffed his advances. Carr stabbed him to death with his Boy Scout pocket knife, bound his hands and feet, and threw him in the river. He went first to Burroughs and then to Kerouac for help. Kerouac allegedly helped him dispose of some of the evidence. But Carr eventually turned himself in and both Burroughs and Kerouac were arrested as material witnesses in the case. After a sensational trial with lurid suggestions of predatory homosexuality, Carr was found guilty of manslaughter and served two years in prison.

Kerouac was guilt stricken and the social circle nearly shattered. He would draw on the experience in two books, his well reviewed but little read first novel The Town and the City published in 1950 and again in the last novel he published before his death, Vanity of Duluoz. He and Burroughs began collaboration in 1945 on a novel entitled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, which was published for the first time in its entirety in November 2008.

In 1947 Ginsberg introduced Kerouac to Cassady, a charismatic drifter and ex-con from California. That same year the two set out on the adventures that Kerouac would chronicle in On the Road.

Kerouac’s first novel had been influenced by another stream of consciousness with a penchant for vivid descriptive passages-Thomas Wolfe and was a sprawling multi-generational epic. On the Road was a major departure. Kerouac consciously drew on the phrasing, rhythms, and riffing of bebop jazz for stylistic inspiration.

Publishers were confused and put off. Kerouac struggled for six years to find publisher, re-editing his manuscript several times before Viking picked it up, scrubbed of much of the rawest sexual content.

When released, the book created a sensation-and sensational reviews. The New York Times Was almost over the top in effusive praise, “its publication is a historic occasion in so far as the exposure of an authentic work of art is of any great moment in an age in which the attention is fragmented and the sensibilities are blunted by the superlatives of fashion.” Most other reviews were equally enthusiastic, although the book found conservative critics for its portrayal of sex, drug use, and sympathetic treatment of Reds and minorities. And it gave a name to a restless, rebellious generation-The Beat Generation. And as much as chronicling them, it created them as the young of artistic bent across the country strove to become Sal Paradise, Dean Moriarty, and friends. It continues to influence generations of writers, poets, musicians, artists of all kinds, and dreamy misfits continues.

Kerouac was uncomfortable with his new fame, although it created a market for some of his unpublished manuscripts including Visions of Cody, Dr. Sax, Maggie Cassidy, The Subterraneans, Tristessa, and eventually Visions of Gerard created as he spent the next several years wandering America and Mexico. In California he came under the influence of the mystic nature poet Gary Snyder, with whom he lived and studied Buddhism, and which he recounted in Dharma Bums, his second most famous novel. He continued to drink heavily, use drugs, and have intense failed relationships with women-he married three times but said his mother was the only woman he truly loved. He would settle for a time in places from rural Minnesota to Orlando, Florida, to North Port, New York to write. There were frequent extended visits with friends in the Beat scenes in New York and San Francisco.

After 1958 he lived mainly with his third wife, Stella Sampas and his ailing mother, who influenced his return to Catholicism. His later works include Lonesome Traveler, Big Sur, and Vanity of Duluoz.

Unlike his friends Ginsburg, Burroughs, Snyder, Gregory Corso, and Cassady, who became an icon to a new generation as the driver of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters bus Further in Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Ade Acid Test, Kerouac did not embrace the counter-culture of the Sixties who looked to him as inspiration. Always more politically conservative that Ginsberg, who he dubbed Carlo Marx in On the Road, he became more so late in life. He even became uncomfortable being identified with the Beat Generation he had named. “I’m not a beatnik,” he declared, “I’m a Catholic.”

Kerouac died on October 21, 1969 at the age of 47 of internal bleeding caused by advanced cirrhosis of the liver. He was living in St. Petersburg, Florida at the time with his wife and mother. He was buried near his father back in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Among his many literary heirs is aspiring writer Maureen Murfin, who made Kerouac the subject of final thesis at Columbia College and who made her pilgrimage to view the Scroll. It is entirely fitting that she left home today on the publishing anniversary of On the Road.