Today’s Almanac-July 7, 2010

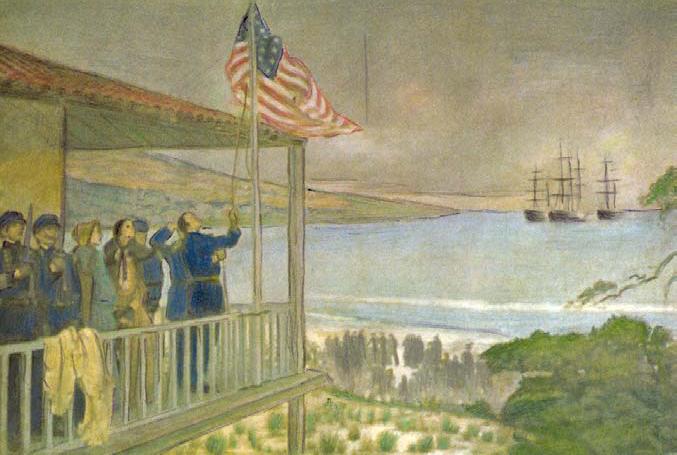

Commodore John Drake Sloat raises the American Flag at Monterey, California.

Other men get most of the credit for the annexation of Alta California during the Mexican War of 1846-’48. But Commodore John Drake Sloat, commander of the U.S. Navy Pacific Squadron, sailed into the harbor at Monterey, the provincial capital, and after a bloodless skirmish with a small force of Mexican Coast Guard and silencing shore batteries with a few well placed salvos, landed with a complement of sailors and Marines. Sloat raised the U.S. flag over the Customs House on July 7, 1846 and issued an edict annexing Alta California to the United States. Two days later he sailed up the coast and took Yerba Buena-today’s San Francisco. He acted as self-proclaimed Military Governor of California until relieved by Commodore Robert F. Stockton, who reprimanded him for exceeding his orders. That reprimand was later echoed by President James K. Polk. Exceed orders of not, with a state of war between the counties, Stockton was not about to hand California back to Mexican authorities. Sloat was a veteran Naval officer. An orphan from New York he had entered the Navy as a midshipman in 1800. He left the service but re-enlisted for the War of 1812. He was serving as Sailing Master under Captain Stephen Decatur on the frigate USS United States when it captured the British frigate HMS Macadonian and was promoted to Lieutenant for conspicuous gallantry under fire in the battle. In his long naval service he had battled Caribbean pirates and commanded several ships before accepting command of the Pacific Squadron in 1844. As tensions with Mexico grew, Sloat was ordered to take Alta California in event of the outbreak of war. He was sailing off of Mazatlán on the Mexican Pacific coast when he got fragmentary reports from shore that fighting had broken out along the Texas border. Without waiting for official confirmation, he raced north to prevent a possible occupation of California by the British from Oregon. Sloat and his successor Stockton soon learned that fighting had already broken out in Northern California and that a Republic had been declared by a handful of settlers from the US. Famed explorer Captain John C. Frémont had entered the rich agricultural Sacramento Valley at the head of a large 55 man “exploration” party early in 1846. His appearance there was something of a mystery, as his official orders were to explore the source of the Arkansas River on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Many historians believe he was acting under secret orders from President Polk, although no evidence of such orders has been found. Others think that the ambitious Frémont acted on his own accord. At any rate, Frémont agitated among the U.S. settler in the valley promising that if war broke out with Mexico that he and his men would, “be there to protect him.” Needless to say, Mexican authorities were unamused. Commandante General José Antonio Castro, a native Californian who was himself often at odds with the distant Mexican government but who was a fierce opponent of foreign immigration, rallied his small force and forced Frémont to north into Oregon. After a battle with Modoc warriors Frémont let a retaliatory attack on a wholly innocent Klamath fishing village massacring the residents. He encountered Marine Corps Lieutenant Archibald H. Gillespie who was carrying secret oral orders for him from the President. He turned his force back south to California with his trusted scout Kit Carson and Lt. Gillespie at his side. When he arrived at Sutter’s Fort on June 25, Frémont found the settlers at Sonoma had declared the Bear Flag Republic on June 14. He took command in the name of the United States and ended the nine day existence of the Republic. Frémont went to work consolidating his force of men from the Army’s Topographical Engineers and experienced mountain men led by Carson with local volunteers, including some Mission Indians. After defeating a small force under Castro at the Battle of Olompali, it seemed that Frémont was in control of California, a situation that did not thrill either Sloat or his successor Stockton. But Stockton had to use his force of sailors and Marines to garrison key points on the coast and to be kept in reserve as “shock” troops should serious fighting break out. He needed to bring Frémont’s California Battalion under his orders and into U.S. service. Frémont was brevetted Lt. Colonel in command of the unit dubbed the U.S. Mounted Rifles with Gillespie as Major and second in command. Carson was appointed a Lieutenant. The volunteers supported a landing by Marines and Bluejackets at San Diego on July 28 followed by taking Los Angeles on August 13. The conquest of California seemed complete. But Major Gillespie, left in command at Los Angeles with 60 men, infuriated the local ranchers with a harsh order of martial law and general contemptuous treatment of local citizens. Previously many had been sympathetic to the possibility of American rule, having become fed up with inept and corrupt government from Mexico City. On September 23 about 200-300 Californios under Gen. José María Flores staged a revolt besieging Gillespie and his garrison without water on Ft. Hill. American volunteer John Brown broke through the Californios’ lines and made a 400 mile ride to contact Stockton in San Fransico Bay. Before Stockton could act to relieve the siege, Gillespie was forced to surrender and was allowed to retreat from Los Angeles to the near-by port of San Pedro. Meanwhile an entirely separate American Force was heading to California overland from Santa Fe. On September 25 about 300 Dragoons under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Kearny began an epic march across deserts and mountains to California. On October 6 he encountered a small party led by Kit Carson which had been sent from Los Angeles in early September with dispatches for President Polk proclaiming victory in California. On the strength of this now outdated news, Kearny sent more than half of his troops back to Santa Fe along with Carson’s dispatches. Carson agreed to turn around and guide Kearny the rest of the way to California by the best possible route. By December 5 Carson brought Kearny's exhausted men to within 25 miles of their destination in San Diego. An intercepted Mexican courier alerted Kearny that Stockton and his forces were under siege in the city. His men mounted mostly on broken mules, Kearny decided to try to raid a the camp of Californios under Andrés Pico at San Pasqual for much needed spare horses. When the camp was alerted Kearny decided to attack. But his 60 remaining exhausted men and their mules were no match for Pico’s skilled lancers who rode rings around the Americans and killed at least 22 of them. Kearny was among the wounded. The Dragoons set up a defensive perimeter and were besieged by Pico. Carson and another man were dispatched to sneak through the lines into San Diego for help. Miraculously, they arrived in the city with bare feet bloody. Stockton dispatched 200 sailor and Marines with fresh horses for Kearny. The arrival of reinforcements caused Pico’s men to scatter. The combined forces entered San Diego on December 12. Kearny’s dispatches reported the Battle of San Pasqual a victory because the Californios “fled the field” when re-enforcements arrived. Stockton reported it as a loss for the Army. The Lancers considered it their victory. After a brief rest Stockton and Kearny’s combined force marched to Los Angeles where they were to join with 400 men under Frémont. On January 8, 1847 with Stockton in command and Kearny his second, approximately 600 men from the San Diego column with artillery support dispersed 150 Californios under José Mariá Flores in the short but sharp Battle of Rio San Gabriel. Remnants of Flores’s men were defeated again the next day at the battle of Battle of La Mesa, the last significant action of the California campaign. American forces re-entered Los Angeles and Major Gillespie personally raised the same American flag he had been forced to haul down months earlier. With fighting essentially over, the commanders fell to bickering among themselves for command. Both Stockton and Kearney held equivalent one-star rank but there was no ordinary precedent for the officer of one service to serve under one of the other of the same rank. Stockton had been on the scene longer and asserted military command as well as the post of military governor. Kearny insisted his orders from Washington were more recent and included both military command and authority to establish a government. Frémont, acting for Stockton signed the Treaty of Cahuenga on January 13 which ended local fighting with the surrender of Californio artillery and return of prisoners on both sides, and which allowed the Californios to return unmolested to their homes without having to surrender Mexican citizenship until a final and comprehensive end to the broader war, which would finally be ended in 1848 by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the official cession of California to the U.S. Stockton appointed Frémont his successor as governor. Frémont, a mere captain in the Regular Army, several times defied a direct order from his Army superior to surrender the Governorship. Kearney appealed to Washington, which confirmed him as Governor. He had Frémont arrested, put in chains, and court marshaled for mutiny and insubordination. Frémont was convicted and sentenced to be dishonorably discharged from the service. Polk upheld the verdict but bowing to pressure from Frémont’s powerful father in law, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and considering his service, vacated the sentence and allowed Frémont to honorably resign his commission. Frémont returned to California where he was subsequently elected Governor and Senator. He was the first Republican Party candidate for President in 1856 and commanded Union forces in Missouri during the Civil War. Kearney saw further service in the Mexican War and was appointed Military Governor of Vera Cruz and then Mexico City. While in Mexico he contracted Yellow Fever. He died of the illness at his home in St. Louis 1848. His rival Stockton resigned from the Navy in 1850 and was elected to the Senate as a Democrat from New Jersey the next year. He was the sponsor of the bill that finally ended flogging in the Navy. In 1861 he was a delegate to an unsuccessful Peace Conference trying to head off the Civil War. He was appointed commander of the New Jersey Militia during the war but saw no action. He died in 1865. Frémont, Stockton, and Kearny-even Kit Carson-were all lauded as heroes for their part in the annexation of California. Place names in several states honor each of them as did Army posts and Navy ships. And what of Commodore Sloat? Ill health ended his career as a sea going officer. He was assigned shore duty, including the planning of the Mare Island Naval Ship Yard at Vallejo, California. He retired from the service in 1866 and died in New York the next year. Largely forgotten, you can find a stone monument to his memory, if you know where to look at the Presidio of Monterey and a couple of streets in residential areas of Monterey and Los Angeles are named in his honor.