Women's HERstory Month Day 20: 25 Women Visual Artists to know part 3

Part 4 will be up later this evening. Sorry for the lull, but hopefully, the other posts made up for it :)

An American Neo-Conceptualist artist, Jenny Holzer (born 1950) utilized the homogeneous rhetoric of modern information systems in order to address the politics of discourse. In 1989 she became the first female artist chosen to represent the United States at Italy's Venice Biennale.

Jenny Holzer was born July 29, 1950, in Gallipolis, Ohio, into a family of two generations of Ford auto dealers. She completed her undergraduate degree at Ohio University in Athens after attending Duke University and the University of Chicago. While enrolled in the Rhode Island School of Design, Holzer experimented with an abstract painting style influenced by the color field painters Mark Rothko and Morris Louis. In 1976 she moved to Manhattan, participating in the Whitney Museum's independent study program.

Holzer's conception of language as art, in which semantics developed into her aesthetic, began to emerge in New York. The Whitney program included an extensive reading list incorporating Western and Eastern literature and philosophy. Holzer felt the writings could be simplified to phrases everyone could understand. She called these summaries her "Truisms" (1978), which she printed anonymously in black italic script on white paper and wheat-pasted to building facades, signs, and telephone booths in lower Manhattan. Arranged in alphabetical order and comprised of short sentences, her "Truisms" inspired pedestrians to scribble messages on the posters and make verbal comments. Holzer would stand and listen to the dialogues invoked by her words.

The participatory effect and the underground format were vital components of Holzer's "Truisms" and of her second series, the "Inflammatory Essays," which laconically articulated Holzer's concerns and anxieties about contemporary society. Holzer printed the "Essays" in alphabetical order, first on small posters and then as a manuscript entitled The Black Book (1979). Until the late 1980s, Holzer refused to produce them in any non-underground formats because of their militant nature. Her declarative language assumed particular force and violence in the multiple viewpoints of the "Essays," ranging from extreme leftist to rightist.

Holzer initiated the "Living Series" in 1981, which she printed on aluminum and bronze plaques, the presentation format used by medical and government buildings. "Living" addressed the necessities of daily life: eating, breathing, sleeping, and human relationships. Her bland, short instructions were accompanied with paintings by the American artist Peter Nadin, whose portraits of men and women attached to metal posts further articulated the emptiness of both life and message in the information age.

The medium of modern computer systems became an important component in Holzer's work in 1982, when nine of her "Truisms" flashed at forty-second intervals on the giant Spectacolor electronic signboard in Times Square. Sponsored by the Public Arts Fund program, the use of the L.E.D. (light emitting diode) machine allowed Holzer to reach a larger audience. By combining a knowledge of semantics with modern advertising technologies, Holzer established herself as a descendant of the conceptualist and Pop Art movements. She again utilized the electronic signboard with her "Survival Series" (1983-1985), in which she adopted a more personal and urgent stance. The realities of everyday living, the dangers, and the underlying horrors were major themes. Correlating with the immediacy of the messages, Holzer adopted a slightly less authoritarian voice. Her populist appropriation of contemporary "newsspeak" crossed the realm between visual art and poetry and carried a potent expressive force.

Her attempt to make sense out of contemporary life within a technological framework also suggests the limitations of the information age, in which the world of advertising consumes everything, yet an underlying message no longer exists.

After the "Survival Series," Holzer's installations became more monumental in scale and more quasi-religious. Her "Under a Rock" exhibition combined the modern media of the communications industry, the electronic signboard, with marble benches printed in the block letters used in national cemeteries. The language measured angst and violence with the apathetic reportage of the most seasoned news personae: CRACK THE PELVIS SO SHE LIES RIGHT, THIS IS A MISTAKE. WHEN SHE DIES YOU CANNOT REPEAT THE ACT, etc. The vivid juxtaposition between horrifying subject matter and the authoritarian voice, coupled with flashing diodes and cold marble, jars the spectator with its apparent paradox and brutal insistency. By utilizing the pronoun "she," Holzer allied the victimization with the female. The new urgency of the "voice" in Holzer's "Under a Rock" installation, first exhibited in 1986 at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York, revealed a Holzer more overtly building images that suggest male power and control over women.

The birth of her first child in 1989 inspired Holzer's "Laments," perhaps the most personal and angst-ridden series she had done. The "Laments" address motherhood, violation, pain, torture, and death in the voices of "thirteen assorted dead people" (J. Holzer). The personae range in sex and age, yet a common insistency permeates their disembodied words. One passage suggests infanticide: IF THE PROCESS STARTS I WILL KILL THIS BABY A GOOD WAY. The contradictions inherent to the rhetoric, "to kill" but in "a good way," shape the negations and arbitrariness of contemporary linguistics. Holzer accessed the language structure and media of contemporary politics and advertising in order to reveal the tensions and male domination apparent in the contemporary linguistic system.

The multimedia extravaganzas of Holzer's later installations, such as the 1989 Guggenheim exhibition, are exemplified by a 535-foot running electronic signboard spiraled around the core of Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture, flashing garish lights on the monumental stone benches arranged in a large circle on the floor below. In 1989 also, she became the first female artist chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, the international art world's premiere event. For the Biennale, Holzer designed posters, hats, and t-shirts to be sold in the streets of Venice, while her L.E.D. signboards and marble benches occupied the solemn and austere exhibition space. Her words were translated into multiple languages in order to communicate to an international audience. Despite the fact that she had won the prestigious Golden Lion award at the Biennale, Holzer also started to draw more negative reactions to her work. The size and expense of her exhibits, as well as her growing popularity in the art world, led some to accuse her of becoming elitist.

Holzer withdrew from the art world for a few years and then returned in 1993 with a fresh approach to her work and a new emphasis on the immaterial. In October of 1993 she partook in a virtual reality exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum. The following year she produced her next series, "Lustmord," which opened at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York. The title is taken from a German word that means murder plus sexual pleasure. She was inspired by the violence of the war in Bosnia, formerly a republic of Yugoslavia. In 1996 she participated in the First Biennale of Florence. By accepting multivalent formats for her media-conscious verbal imagery, Holzer created a populist art of expressive and poetic force.

Kara Walker was born Nov. 26, 1969 in Stockton, California. At the Rhode Island School of Design, she began working in the silhouette form. In 1994 her work appeared in a new-talent show at the Drawing Center in New York. Her work caused a stir. In 1997 she received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.” Her work was exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide.

American artist who used intricately cut paper silhouettes to comment on race and gender relations.

Her father, Larry Walker, was an artist and chair of the art department at the University of the Pacific in Stockton. She showed promise as an artist from a young age, but it was not until the family moved to Georgia when she was 13 that she began to focus on issues of race. Walker received a bachelor's degree (1991) from the Atlanta College of Art and a master's degree (1994) from the Rhode Island School of Design, where she began working in the silhouette form while exploring themes of slavery, violence, and sex found in sources such as books, films, and cartoons.

Later in 1994 Walker's work appeared in a new-talent show at the Drawing Center in New York. Her contribution was a 50-foot (15-metre) mural of life-size silhouettes depicting a set of disturbing scenes set in the antebellum South. The piece was titled Gone, a Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Negress and Her Heart. That work and subsequent others, such as a series of watercolours titled Negress Notes (Brown Follies) (1996-97), caused a stir. Some African American artists, particularly those of the civil rights era, deplored her use of racist caricatures. Walker made it clear that her intent as an artist was not to create pleasing images or to raise questions with easy answers.

In 1997, at age 27, Walker received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.” Her work was exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide, and she served as the U.S. representative to the 2002 Sao Paulo Biennial. She was also on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University in New York City. In 2006 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City featured her exhibition titled “After the Deluge,” which was inspired in part by the devastation wreaked the previous year by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The exhibition juxtaposed pieces from the museum's own collection-many of which depicted black figures or images demonstrating the terrific power of water-with some of her own works. The intermingled disparate images created an amalgam of new meaning fraught with a discomfiting ambiguity characteristic of much of Walker's output.

Barbara Kruger was born on January 26, 1945, in Newark, New Jersey. She spent a year at Syracuse University in 1964 and a semester at Parsons School of Design in New York in 1965, where she studied with Diane Arbus and graphic designer Marvin Israel. In 1966, she took a job with Condé Nast, working in the design department of Mademoiselle. She was named that magazine’s head designer a year later. For the next decade, Kruger supported herself doing graphic design for magazines, book jacket designs, and freelance picture editing. In the late 1960s, she also developed an interest in poetry, attending readings and writing.

Kruger’s earliest artworks date to 1969. Large woven wall hangings of yarn, beads, sequins, feathers, and ribbons, they exemplify the feminist recuperation of craft during this period. Despite her inclusion in the Whitney Biennial in 1973 and solo exhibitions at Artists Space and Fischbach Gallery, both in New York, the following two years, she was dissatisfied with her output and its detachment from her growing social and political concerns. In the fall of 1976, Kruger abandoned art making and moved to Berkeley, California, where she taught at the University of California for four years and steeped herself in the writings of Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes. She took up photography in 1977, producing a series of black-and-white details of architectural exteriors paired with her own textual ruminations on the lives of those living inside. Published as an artist’s book, Picture/Readings (1979) foreshadows the aesthetic vocabulary Kruger developed in her mature work.

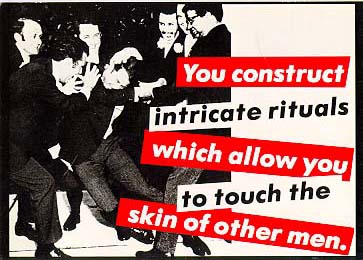

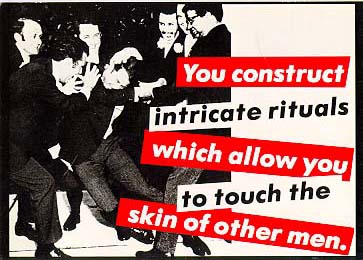

By 1979, Kruger stopped taking photographs and began to employ found images in her art, mostly from mid-century American print-media sources, with words collaged directly over them. Untitled (Perfect) (1980) portrays the torso of a woman, hands clasped in prayer, evoking the Virgin Mary, the embodiment of submissive femininity; the word “perfect” is emblazoned along the lower edge of the image. These early collages, in which Kruger deployed techniques she had perfected as a graphic designer, inaugurated the artist’s ongoing political, social, and especially feminist provocations and commentaries on religion, sexuality, racial and gender stereotypes, consumerism, corporate greed, and power.

During the early 1980s, Kruger perfected a signature agitprop style, using cropped, large-scale, black-and-white photographic images juxtaposed with raucous, pithy, and often ironic aphorisms, printed in Futura Bold typeface against black, white, or deep red text bars. The inclusion of personal pronouns in works like Untitled (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face) (1981) and Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987) implicates viewers by confounding any clear notion of who is speaking. These rigorously composed mature works function successfully on any scale. Their wide distribution-under the artist’s supervision-in the form of umbrellas, tote bags, postcards, mugs, T-shirts, posters, and so on, confuses the boundaries between art and commerce and calls attention to the role of the advertising in public debate.

In recent years, Kruger has extended her aesthetic project, creating public installations of her work in galleries, museums, municipal buildings, train stations, and parks, as well as on buses and billboards around the world. Walls, floors, and ceilings are covered with images and texts, which engulf and even assault the viewer. Since the late 1990s, Kruger has incorporated sculpture into her ongoing critique of modern American culture. Justice (1997), in white-painted fiberglass, depicts J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn-two right-wing public figures who hid their homosexuality-in partial drag, kissing one another. In this kitsch send-up of commemorative statuary, Kruger highlights the conspiracy of silence that enabled these two men to accrue social and political power.

Major solo exhibitions of Kruger’s work have been organized by the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (1983), Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1999), and Palazzo delle Papesse Centro Arte Contemporanea in Siena (2002). She represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1982. Kruger lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

Remedios Varo's storied life began in 1908 when she was born in Spain. She fled the Spanish Civil War and headed to Paris to further her artistry in Surrealism. The surrealist movement was strong there and she honed her skills along with painters who received more notoriety.

The Nazi occupation of France forced Varo into exile. She made it out safe and in 1941 arrived in Mexico City where she remained the remainder of her life. She befriended famous artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera while in Mexico. During the 1950's Remedios Varo further developed her remarkable and unique style. Her most popular medium was oil on masonite panels which she prepared herself. Varo's brushwork involved repeated fine strokes of paint laid in close proximity to each other.

Remedios Varo's artistic influences included the work of Hieronymus Bosch. Critics have described her painting as "postmodern allegory" and in the tradition of Irrealism. She was also influenced by styles in other realms including Picasso, Francisco Goya, El Greco, and Braque. Andre Breton was a formative influence in Varo's understanding of Surrealism. Further artistic influence can be seen in her paintings of the modern Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. While in Mexico, Varo became influenced by the primitive art ancient Columbian culture. Her painting titled "The Lovers" has served as an inspiration for images used by Madonna in the music video for her 1996 single "Bedtime Story".

Philosophically, Varo was influenced by a many mystic traditions of both Eastern and Western society. She studied the ideas of G. I. Gurdjieff, C. G. Jung, Ouspensky, Sufis, H. Blavatsky, and Meister Eckhart. The legend of the Holy Grail fascinated Varo along with sacred geometry and alchemy. She believed that through each of these there was a path self-enlightenment and the transformation of consciousness.

Remedios Varo died at the height of her career in 1961. Her art continues to achieve successful retrospectives today. Her popularity has picked up in recent years especially in North America where art connoisseurs discover her mastery.

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon, as her name appears on her birth certificate was born on July 6, 1907 in the house of her parents, known as La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacan. At the time, this was a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Her father, Guillermo Kahlo (1872-1941), was born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in Pforzheim, Germany. He was the son of the painter and goldsmith Jakob Heinrich Kahlo and Henriett E. Kaufmann.

Kahlo claimed her father was of Jewish and Hungarian ancestry, but a 2005 book on Guillermo Kahlo, Fridas Vater (Schirmer/Mosel, 2005), states that he was descended from a long line of German Lutherans.

Wilhelm Kahlo sailed to Mexico in 1891 at the age of nineteen and, upon his arrival, changed his German forename, Wilhelm, to its Spanish equivalent, 'Guillermo'. During the late 1930s, in the face of rising Nazism in Germany, Frida acknowledged and asserted her German heritage by spelling her name, Frieda (an allusion to "Frieden", which means "peace" in German).

Frida's mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was a devout Catholic of primarily indigenous, as well as Spanish descent. Frida's parents were married shortly after the death of Guillermo's first wife during the birth of her second child. Although their marriage was quite unhappy, Guillermo and Matilde had four daughters, with Frida being the third. She had two older half sisters. Frida once remarked that she grew up in a world surrounded by females. Throughout most of her life, however, Frida remained close to her father.

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910 when Kahlo was three years old. Later, however, Kahlo claimed that she was born in 1910 so people would directly associate her with the revolution. In her writings, she recalled that her mother would usher her and her sisters inside the house as gunfire echoed in the streets of her hometown, which was extremely poor at the time. Occasionally, men would leap over the walls into their backyard and sometimes her mother would prepare a meal for the hungry revolutionaries.

Kahlo contracted polio at age six, which left her right leg thinner than the left, which Kahlo disguised by wearing long skirts. It has been conjectured that she also suffered from spina bifida, a congenital disease that could have affected both spinal and leg development. As a girl, she participated in boxing and other sports. In 1922, Kahlo was enrolled in the Preparatoria, one of Mexico's premier schools, where she was one of only thirty-five girls. Kahlo joined a gang at the school and fell in love with the leader, Alejandro Gomez Arias. During this period, Kahlo also witnessed violent armed struggles in the streets of Mexico City as the Mexican Revolution continued.

After the accident, Frida Kahlo turned her attention away from the study of medicine to begin a full-time painting career. The accident left her in a great deal of pain while she recovered in a full body cast; she painted to occupy her time during her temporary state of immobilization. Her self-portraits became a dominant part of her life when she was immobile for three months after her accident. Frida Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best". Her mother had a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed, and her father lent her his box of oil paints and some brushes.

Drawing on personal experiences, including her marriage, her miscarriages, and her numerous operations, Kahlo's works often are characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds. She insisted, "I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality".

Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her use of bright colors and dramatic symbolism. She frequently included the symbolic monkey. In Mexican mythology, monkeys are symbols of lust, yet Kahlo portrayed them as tender and protective symbols. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work. She combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition with surrealist renderings.

At the invitation of Andre Breton, she went to France in 1939 and was featured at an exhibition of her paintings in Paris. The Louvre bought one of her paintings, The Frame, which was displayed at the exhibit. This was the first work by a 20th century Mexican artist ever purchased by the internationally renowned museum.

As a young artist, Kahlo approached the famous Mexican painter, Diego Rivera, whose work she admired, asking him for advice about pursuing art as a career. He immediately recognized her talent and her unique expression as truly special and uniquely Mexican. He encouraged her development as an artist and soon began an intimate relationship with Frida. They were married in 1929, despite the disapproval of Frida's mother. They often were referred to as The Elephant and the Dove, a nickname that originated when Kahlo's father used it to express their extreme difference in size.

Their marriage often was tumultuous. Notoriously, both Kahlo and Rivera had fiery temperaments and both had numerous extramarital affairs. The openly bisexual Kahlo had affairs with both men (including Leon Trotsky) and women; Rivera knew of and tolerated her relationships with women, but her relationships with men made him jealous. For her part, Kahlo became outraged when she learned that Rivera had an affair with her younger sister, Cristina. The couple eventually divorced, but remarried in 1940. Their second marriage was as turbulent as the first. Their living quarters often were separate, although sometimes adjacent.

Active communist sympathizers, Kahlo and Rivera befriended Leon Trotsky as he sought political sanctuary from Joseph Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union. Initially, Trotsky lived with Rivera and then at Kahlo's home, where they reportedly had an affair. Trotsky and his wife then moved to another house in Coyoacan where, later, he was assassinated.

A few days before Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, she wrote in her diary: "I hope the exit is joyful - and I hope never to return - Frida". The official cause of death was given as pulmonary embolism, although some suspected that she died from overdose that may or may not have been accidental. An autopsy was never performed. She had been very ill throughout the previous year and her right leg had been amputated at the knee, owing to gangrene. She also had a bout of bronchopneumonia near that time, which had left her quite frail.

Later, in his autobiography, Diego Rivera wrote that the day Kahlo died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.

A pre-Columbian urn holding her ashes is on display in her former home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacan. Today it is a museum housing a number of her works of art and numerous relics from her personal life.

Sources: Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, Barbara Kruger, Remidios Varo,Frida Kahlo

An American Neo-Conceptualist artist, Jenny Holzer (born 1950) utilized the homogeneous rhetoric of modern information systems in order to address the politics of discourse. In 1989 she became the first female artist chosen to represent the United States at Italy's Venice Biennale.

Jenny Holzer was born July 29, 1950, in Gallipolis, Ohio, into a family of two generations of Ford auto dealers. She completed her undergraduate degree at Ohio University in Athens after attending Duke University and the University of Chicago. While enrolled in the Rhode Island School of Design, Holzer experimented with an abstract painting style influenced by the color field painters Mark Rothko and Morris Louis. In 1976 she moved to Manhattan, participating in the Whitney Museum's independent study program.

Holzer's conception of language as art, in which semantics developed into her aesthetic, began to emerge in New York. The Whitney program included an extensive reading list incorporating Western and Eastern literature and philosophy. Holzer felt the writings could be simplified to phrases everyone could understand. She called these summaries her "Truisms" (1978), which she printed anonymously in black italic script on white paper and wheat-pasted to building facades, signs, and telephone booths in lower Manhattan. Arranged in alphabetical order and comprised of short sentences, her "Truisms" inspired pedestrians to scribble messages on the posters and make verbal comments. Holzer would stand and listen to the dialogues invoked by her words.

The participatory effect and the underground format were vital components of Holzer's "Truisms" and of her second series, the "Inflammatory Essays," which laconically articulated Holzer's concerns and anxieties about contemporary society. Holzer printed the "Essays" in alphabetical order, first on small posters and then as a manuscript entitled The Black Book (1979). Until the late 1980s, Holzer refused to produce them in any non-underground formats because of their militant nature. Her declarative language assumed particular force and violence in the multiple viewpoints of the "Essays," ranging from extreme leftist to rightist.

Holzer initiated the "Living Series" in 1981, which she printed on aluminum and bronze plaques, the presentation format used by medical and government buildings. "Living" addressed the necessities of daily life: eating, breathing, sleeping, and human relationships. Her bland, short instructions were accompanied with paintings by the American artist Peter Nadin, whose portraits of men and women attached to metal posts further articulated the emptiness of both life and message in the information age.

The medium of modern computer systems became an important component in Holzer's work in 1982, when nine of her "Truisms" flashed at forty-second intervals on the giant Spectacolor electronic signboard in Times Square. Sponsored by the Public Arts Fund program, the use of the L.E.D. (light emitting diode) machine allowed Holzer to reach a larger audience. By combining a knowledge of semantics with modern advertising technologies, Holzer established herself as a descendant of the conceptualist and Pop Art movements. She again utilized the electronic signboard with her "Survival Series" (1983-1985), in which she adopted a more personal and urgent stance. The realities of everyday living, the dangers, and the underlying horrors were major themes. Correlating with the immediacy of the messages, Holzer adopted a slightly less authoritarian voice. Her populist appropriation of contemporary "newsspeak" crossed the realm between visual art and poetry and carried a potent expressive force.

Her attempt to make sense out of contemporary life within a technological framework also suggests the limitations of the information age, in which the world of advertising consumes everything, yet an underlying message no longer exists.

After the "Survival Series," Holzer's installations became more monumental in scale and more quasi-religious. Her "Under a Rock" exhibition combined the modern media of the communications industry, the electronic signboard, with marble benches printed in the block letters used in national cemeteries. The language measured angst and violence with the apathetic reportage of the most seasoned news personae: CRACK THE PELVIS SO SHE LIES RIGHT, THIS IS A MISTAKE. WHEN SHE DIES YOU CANNOT REPEAT THE ACT, etc. The vivid juxtaposition between horrifying subject matter and the authoritarian voice, coupled with flashing diodes and cold marble, jars the spectator with its apparent paradox and brutal insistency. By utilizing the pronoun "she," Holzer allied the victimization with the female. The new urgency of the "voice" in Holzer's "Under a Rock" installation, first exhibited in 1986 at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York, revealed a Holzer more overtly building images that suggest male power and control over women.

The birth of her first child in 1989 inspired Holzer's "Laments," perhaps the most personal and angst-ridden series she had done. The "Laments" address motherhood, violation, pain, torture, and death in the voices of "thirteen assorted dead people" (J. Holzer). The personae range in sex and age, yet a common insistency permeates their disembodied words. One passage suggests infanticide: IF THE PROCESS STARTS I WILL KILL THIS BABY A GOOD WAY. The contradictions inherent to the rhetoric, "to kill" but in "a good way," shape the negations and arbitrariness of contemporary linguistics. Holzer accessed the language structure and media of contemporary politics and advertising in order to reveal the tensions and male domination apparent in the contemporary linguistic system.

The multimedia extravaganzas of Holzer's later installations, such as the 1989 Guggenheim exhibition, are exemplified by a 535-foot running electronic signboard spiraled around the core of Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture, flashing garish lights on the monumental stone benches arranged in a large circle on the floor below. In 1989 also, she became the first female artist chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, the international art world's premiere event. For the Biennale, Holzer designed posters, hats, and t-shirts to be sold in the streets of Venice, while her L.E.D. signboards and marble benches occupied the solemn and austere exhibition space. Her words were translated into multiple languages in order to communicate to an international audience. Despite the fact that she had won the prestigious Golden Lion award at the Biennale, Holzer also started to draw more negative reactions to her work. The size and expense of her exhibits, as well as her growing popularity in the art world, led some to accuse her of becoming elitist.

Holzer withdrew from the art world for a few years and then returned in 1993 with a fresh approach to her work and a new emphasis on the immaterial. In October of 1993 she partook in a virtual reality exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum. The following year she produced her next series, "Lustmord," which opened at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York. The title is taken from a German word that means murder plus sexual pleasure. She was inspired by the violence of the war in Bosnia, formerly a republic of Yugoslavia. In 1996 she participated in the First Biennale of Florence. By accepting multivalent formats for her media-conscious verbal imagery, Holzer created a populist art of expressive and poetic force.

Kara Walker was born Nov. 26, 1969 in Stockton, California. At the Rhode Island School of Design, she began working in the silhouette form. In 1994 her work appeared in a new-talent show at the Drawing Center in New York. Her work caused a stir. In 1997 she received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.” Her work was exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide.

American artist who used intricately cut paper silhouettes to comment on race and gender relations.

Her father, Larry Walker, was an artist and chair of the art department at the University of the Pacific in Stockton. She showed promise as an artist from a young age, but it was not until the family moved to Georgia when she was 13 that she began to focus on issues of race. Walker received a bachelor's degree (1991) from the Atlanta College of Art and a master's degree (1994) from the Rhode Island School of Design, where she began working in the silhouette form while exploring themes of slavery, violence, and sex found in sources such as books, films, and cartoons.

Later in 1994 Walker's work appeared in a new-talent show at the Drawing Center in New York. Her contribution was a 50-foot (15-metre) mural of life-size silhouettes depicting a set of disturbing scenes set in the antebellum South. The piece was titled Gone, a Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Negress and Her Heart. That work and subsequent others, such as a series of watercolours titled Negress Notes (Brown Follies) (1996-97), caused a stir. Some African American artists, particularly those of the civil rights era, deplored her use of racist caricatures. Walker made it clear that her intent as an artist was not to create pleasing images or to raise questions with easy answers.

In 1997, at age 27, Walker received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.” Her work was exhibited in galleries and museums worldwide, and she served as the U.S. representative to the 2002 Sao Paulo Biennial. She was also on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University in New York City. In 2006 the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City featured her exhibition titled “After the Deluge,” which was inspired in part by the devastation wreaked the previous year by Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. The exhibition juxtaposed pieces from the museum's own collection-many of which depicted black figures or images demonstrating the terrific power of water-with some of her own works. The intermingled disparate images created an amalgam of new meaning fraught with a discomfiting ambiguity characteristic of much of Walker's output.

Barbara Kruger was born on January 26, 1945, in Newark, New Jersey. She spent a year at Syracuse University in 1964 and a semester at Parsons School of Design in New York in 1965, where she studied with Diane Arbus and graphic designer Marvin Israel. In 1966, she took a job with Condé Nast, working in the design department of Mademoiselle. She was named that magazine’s head designer a year later. For the next decade, Kruger supported herself doing graphic design for magazines, book jacket designs, and freelance picture editing. In the late 1960s, she also developed an interest in poetry, attending readings and writing.

Kruger’s earliest artworks date to 1969. Large woven wall hangings of yarn, beads, sequins, feathers, and ribbons, they exemplify the feminist recuperation of craft during this period. Despite her inclusion in the Whitney Biennial in 1973 and solo exhibitions at Artists Space and Fischbach Gallery, both in New York, the following two years, she was dissatisfied with her output and its detachment from her growing social and political concerns. In the fall of 1976, Kruger abandoned art making and moved to Berkeley, California, where she taught at the University of California for four years and steeped herself in the writings of Walter Benjamin and Roland Barthes. She took up photography in 1977, producing a series of black-and-white details of architectural exteriors paired with her own textual ruminations on the lives of those living inside. Published as an artist’s book, Picture/Readings (1979) foreshadows the aesthetic vocabulary Kruger developed in her mature work.

By 1979, Kruger stopped taking photographs and began to employ found images in her art, mostly from mid-century American print-media sources, with words collaged directly over them. Untitled (Perfect) (1980) portrays the torso of a woman, hands clasped in prayer, evoking the Virgin Mary, the embodiment of submissive femininity; the word “perfect” is emblazoned along the lower edge of the image. These early collages, in which Kruger deployed techniques she had perfected as a graphic designer, inaugurated the artist’s ongoing political, social, and especially feminist provocations and commentaries on religion, sexuality, racial and gender stereotypes, consumerism, corporate greed, and power.

During the early 1980s, Kruger perfected a signature agitprop style, using cropped, large-scale, black-and-white photographic images juxtaposed with raucous, pithy, and often ironic aphorisms, printed in Futura Bold typeface against black, white, or deep red text bars. The inclusion of personal pronouns in works like Untitled (Your Gaze Hits the Side of My Face) (1981) and Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am) (1987) implicates viewers by confounding any clear notion of who is speaking. These rigorously composed mature works function successfully on any scale. Their wide distribution-under the artist’s supervision-in the form of umbrellas, tote bags, postcards, mugs, T-shirts, posters, and so on, confuses the boundaries between art and commerce and calls attention to the role of the advertising in public debate.

In recent years, Kruger has extended her aesthetic project, creating public installations of her work in galleries, museums, municipal buildings, train stations, and parks, as well as on buses and billboards around the world. Walls, floors, and ceilings are covered with images and texts, which engulf and even assault the viewer. Since the late 1990s, Kruger has incorporated sculpture into her ongoing critique of modern American culture. Justice (1997), in white-painted fiberglass, depicts J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn-two right-wing public figures who hid their homosexuality-in partial drag, kissing one another. In this kitsch send-up of commemorative statuary, Kruger highlights the conspiracy of silence that enabled these two men to accrue social and political power.

Major solo exhibitions of Kruger’s work have been organized by the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London (1983), Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (1999), and Palazzo delle Papesse Centro Arte Contemporanea in Siena (2002). She represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1982. Kruger lives and works in New York and Los Angeles.

Remedios Varo's storied life began in 1908 when she was born in Spain. She fled the Spanish Civil War and headed to Paris to further her artistry in Surrealism. The surrealist movement was strong there and she honed her skills along with painters who received more notoriety.

The Nazi occupation of France forced Varo into exile. She made it out safe and in 1941 arrived in Mexico City where she remained the remainder of her life. She befriended famous artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera while in Mexico. During the 1950's Remedios Varo further developed her remarkable and unique style. Her most popular medium was oil on masonite panels which she prepared herself. Varo's brushwork involved repeated fine strokes of paint laid in close proximity to each other.

Remedios Varo's artistic influences included the work of Hieronymus Bosch. Critics have described her painting as "postmodern allegory" and in the tradition of Irrealism. She was also influenced by styles in other realms including Picasso, Francisco Goya, El Greco, and Braque. Andre Breton was a formative influence in Varo's understanding of Surrealism. Further artistic influence can be seen in her paintings of the modern Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico. While in Mexico, Varo became influenced by the primitive art ancient Columbian culture. Her painting titled "The Lovers" has served as an inspiration for images used by Madonna in the music video for her 1996 single "Bedtime Story".

Philosophically, Varo was influenced by a many mystic traditions of both Eastern and Western society. She studied the ideas of G. I. Gurdjieff, C. G. Jung, Ouspensky, Sufis, H. Blavatsky, and Meister Eckhart. The legend of the Holy Grail fascinated Varo along with sacred geometry and alchemy. She believed that through each of these there was a path self-enlightenment and the transformation of consciousness.

Remedios Varo died at the height of her career in 1961. Her art continues to achieve successful retrospectives today. Her popularity has picked up in recent years especially in North America where art connoisseurs discover her mastery.

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderon, as her name appears on her birth certificate was born on July 6, 1907 in the house of her parents, known as La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacan. At the time, this was a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Her father, Guillermo Kahlo (1872-1941), was born Carl Wilhelm Kahlo in Pforzheim, Germany. He was the son of the painter and goldsmith Jakob Heinrich Kahlo and Henriett E. Kaufmann.

Kahlo claimed her father was of Jewish and Hungarian ancestry, but a 2005 book on Guillermo Kahlo, Fridas Vater (Schirmer/Mosel, 2005), states that he was descended from a long line of German Lutherans.

Wilhelm Kahlo sailed to Mexico in 1891 at the age of nineteen and, upon his arrival, changed his German forename, Wilhelm, to its Spanish equivalent, 'Guillermo'. During the late 1930s, in the face of rising Nazism in Germany, Frida acknowledged and asserted her German heritage by spelling her name, Frieda (an allusion to "Frieden", which means "peace" in German).

Frida's mother, Matilde Calderon y Gonzalez, was a devout Catholic of primarily indigenous, as well as Spanish descent. Frida's parents were married shortly after the death of Guillermo's first wife during the birth of her second child. Although their marriage was quite unhappy, Guillermo and Matilde had four daughters, with Frida being the third. She had two older half sisters. Frida once remarked that she grew up in a world surrounded by females. Throughout most of her life, however, Frida remained close to her father.

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910 when Kahlo was three years old. Later, however, Kahlo claimed that she was born in 1910 so people would directly associate her with the revolution. In her writings, she recalled that her mother would usher her and her sisters inside the house as gunfire echoed in the streets of her hometown, which was extremely poor at the time. Occasionally, men would leap over the walls into their backyard and sometimes her mother would prepare a meal for the hungry revolutionaries.

Kahlo contracted polio at age six, which left her right leg thinner than the left, which Kahlo disguised by wearing long skirts. It has been conjectured that she also suffered from spina bifida, a congenital disease that could have affected both spinal and leg development. As a girl, she participated in boxing and other sports. In 1922, Kahlo was enrolled in the Preparatoria, one of Mexico's premier schools, where she was one of only thirty-five girls. Kahlo joined a gang at the school and fell in love with the leader, Alejandro Gomez Arias. During this period, Kahlo also witnessed violent armed struggles in the streets of Mexico City as the Mexican Revolution continued.

After the accident, Frida Kahlo turned her attention away from the study of medicine to begin a full-time painting career. The accident left her in a great deal of pain while she recovered in a full body cast; she painted to occupy her time during her temporary state of immobilization. Her self-portraits became a dominant part of her life when she was immobile for three months after her accident. Frida Kahlo once said, "I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best". Her mother had a special easel made for her so she could paint in bed, and her father lent her his box of oil paints and some brushes.

Drawing on personal experiences, including her marriage, her miscarriages, and her numerous operations, Kahlo's works often are characterized by their stark portrayals of pain. Of her 143 paintings, 55 are self-portraits which often incorporate symbolic portrayals of physical and psychological wounds. She insisted, "I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality".

Kahlo was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which is apparent in her use of bright colors and dramatic symbolism. She frequently included the symbolic monkey. In Mexican mythology, monkeys are symbols of lust, yet Kahlo portrayed them as tender and protective symbols. Christian and Jewish themes are often depicted in her work. She combined elements of the classic religious Mexican tradition with surrealist renderings.

At the invitation of Andre Breton, she went to France in 1939 and was featured at an exhibition of her paintings in Paris. The Louvre bought one of her paintings, The Frame, which was displayed at the exhibit. This was the first work by a 20th century Mexican artist ever purchased by the internationally renowned museum.

As a young artist, Kahlo approached the famous Mexican painter, Diego Rivera, whose work she admired, asking him for advice about pursuing art as a career. He immediately recognized her talent and her unique expression as truly special and uniquely Mexican. He encouraged her development as an artist and soon began an intimate relationship with Frida. They were married in 1929, despite the disapproval of Frida's mother. They often were referred to as The Elephant and the Dove, a nickname that originated when Kahlo's father used it to express their extreme difference in size.

Their marriage often was tumultuous. Notoriously, both Kahlo and Rivera had fiery temperaments and both had numerous extramarital affairs. The openly bisexual Kahlo had affairs with both men (including Leon Trotsky) and women; Rivera knew of and tolerated her relationships with women, but her relationships with men made him jealous. For her part, Kahlo became outraged when she learned that Rivera had an affair with her younger sister, Cristina. The couple eventually divorced, but remarried in 1940. Their second marriage was as turbulent as the first. Their living quarters often were separate, although sometimes adjacent.

Active communist sympathizers, Kahlo and Rivera befriended Leon Trotsky as he sought political sanctuary from Joseph Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union. Initially, Trotsky lived with Rivera and then at Kahlo's home, where they reportedly had an affair. Trotsky and his wife then moved to another house in Coyoacan where, later, he was assassinated.

A few days before Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954, she wrote in her diary: "I hope the exit is joyful - and I hope never to return - Frida". The official cause of death was given as pulmonary embolism, although some suspected that she died from overdose that may or may not have been accidental. An autopsy was never performed. She had been very ill throughout the previous year and her right leg had been amputated at the knee, owing to gangrene. She also had a bout of bronchopneumonia near that time, which had left her quite frail.

Later, in his autobiography, Diego Rivera wrote that the day Kahlo died was the most tragic day of his life, adding that, too late, he had realized that the most wonderful part of his life had been his love for her.

A pre-Columbian urn holding her ashes is on display in her former home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), in Coyoacan. Today it is a museum housing a number of her works of art and numerous relics from her personal life.

Sources: Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, Barbara Kruger, Remidios Varo,Frida Kahlo