Women's HERstory Month Day Sixteen: Women Artists to Know, Part 2

I'm very glad the last post was well-received! I always love to see people loving art <3

Today, we will be covering these five brilliant women:

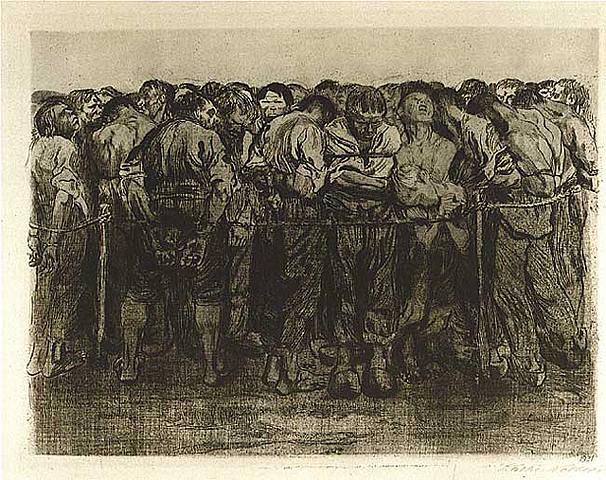

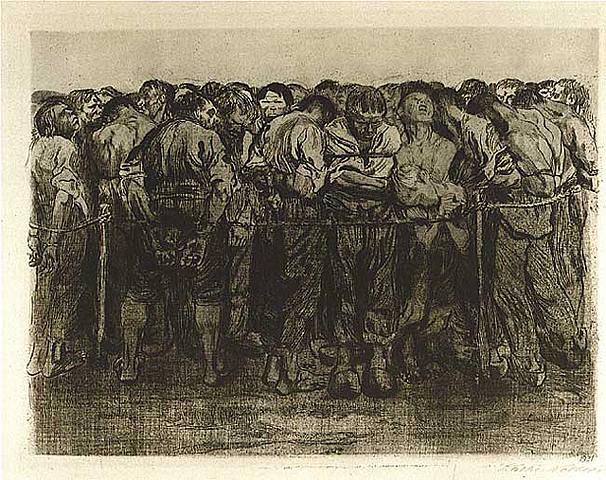

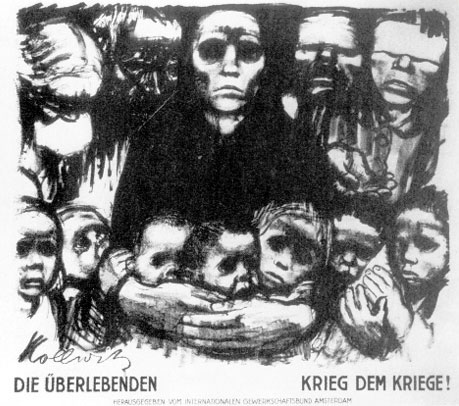

Käthe Kollwitz was born July 8, 1867 in Kaliningrad, Russia. She devoted herself primarily to graphic art after 1890. Her first important works were two separate series of prints, Weavers' Revolt and Peasants' War. The death of her youngest in 1914 led to another cycle of prints of a mother protecting her children. Her last great series of lithographs was Death.

The artist grew up in a liberal middle-class family and studied painting in Berlin (1884-85) and Munich (1888-89). Impressed by the prints of Max Klinger, she devoted herself primarily to graphic art after 1890, producing etchings, lithographs, woodcuts, and drawings. In 1891 she married Karl Kollwitz, a doctor who opened a clinic in a working-class section of Berlin. There she gained firsthand insight into the miserable conditions of the urban poor.

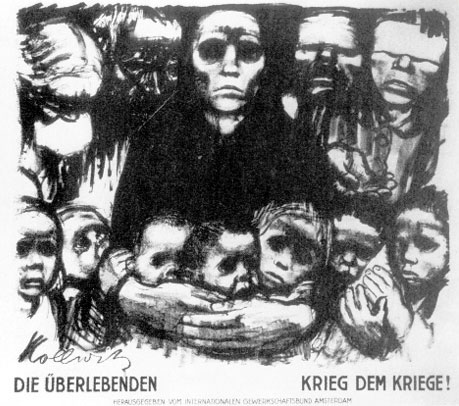

Kollwitz's first important works were two separate series of prints, respectively entitled Weavers' Revolt (c. 1894-98) and Peasants' War (1902-08). In these works she portrayed the plight of the poor and oppressed with the powerfully simplified, boldly accentuated forms that became her trademark. The death of her youngest son in battle in 1914 profoundly affected her, and she expressed her grief in another cycle of prints that treat the themes of a mother protecting her children, and of a mother with a dead child. From 1924 to 1932 Kollwitz also worked on a granite monument for her son, which depicted her husband and herself as grieving parents. In 1932 it was erected as a memorial in a cemetery near Ypres, Belgium.

Kollwitz greeted the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the German revolution of 1918 with hope, but she eventually became disillusioned with Soviet communism. During the years of the Weimar Republic, she became the first woman to be elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, where from 1928 to 1933 she was head of the Master Studio for Graphic Arts. Kollwitz continued to devote herself to socially effective, easily understood art. The Nazis' rise to power in Germany in 1933 led to her forced resignation from the academy.

Kollwitz's last great series of lithographs, Death (1934-36), treats that tragic theme with stark and monumental forms that convey a sense of drama. In 1940 her husband died, and in 1942 her grandson was killed in action during World War II. The bombing of Kollwitz's home and studio in 1943 destroyed much of her life's work. She died a few weeks before the end of the war in Europe. Kollwitz was the last great practitioner of German Expressionism and is often considered to be the foremost artist of social protest in the 20th century. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz was published in 1988.

Tracey Emin, Ph.D., was born in Croydon, England on July 3, 1963. She was a Professor of Confessional Art at the European Graduate School (EGS) where she gave a guest lecture. A London-based artist, Tracey Emin has been recognized as one of the leading figures of the YBA (Young British Artists) in the 1990s. She graduated in fine arts from the Maidstone College of Art in 1986, and was awarded an MA in painting by the Royal College of Art in 1989. Tracey Emin also studied modern philosophy in London and was on the short list for the Turner Prize in 1999. She has exhibited extensively internationally, with solo shows at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Modern Art Oxford, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, Istanbul, and Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Tracey Emin represented Britain at the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007. In the same year, she was made a Royal Academician and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the Royal College of Art, London, a Doctor of Philosophy from London Metropolitan University and Doctor of Letters from the University of Kent.

Tracey Emin's works are known for their immediacy, raw openness and often sexually provocative attitude which fascinates the viewer. Her art is deeply confessional and she herself has become the embodiment of the artist as a maverick, even outsider celebrity, constantly infuriating the art world and provoking the British class system with her open working-class attitude. Named by David Bowie to be 'William Blake as a woman, written by Mike Leigh', her public persona is loud, dangerous and unpredictable, but at the same time radiates a deeply emotional and vulnerable side. Her controlled exhibition of the self takes a form in exceptionally wide range of media - from appliquéd blankets and sewing, to neons, videos, super-8 films, photographs, animations, watercolors, sculptures, installations, and intensely personal paintings and drawings. One of the aspects of Tracey Emin's work unfairly receiving little attention is her writing - here, she pushes the borders between writing as visual art and visual art as a text, forcing us to rethink the status of both.

Roberta Smith of The New Yorker says the following about Tracey’s work:

"If Tracey Emin could sing, she might be Judy Garland, a bundle of irresistible, pathetic, ferocious, self-indulgent, brilliant energy. Since she can't, or doesn't, she writes, incorporating autobiographical texts and statements into drawings, monoprints, watercolors, collages, quilts, neon sculptures, installations and videotapes. In her art she tells all, all the truths, both awful and wonderful, but mostly awful, about her life. Physical and psychic pain in the form of rejection, incest, rape, abortion and sex with strangers figure in this tale, as do love, passion and joy."

After a difficult childhood, Tracey Emin squatted in London after dropping out of school at thirteen. This period of her life provided a strong inspiration for much of her later work. She studied art in Essex and London, deciding to destroy all her work after a traumatic abortion in 1989. She began working only several years later, reworking her past by producing confessional letters and combining them with mementos from her youth. Tracey Emin presented this material at her first solo exhibition at the White Cube Gallery in London in 1993, provocatively entitled 'My Major Retrospective'. The show told her intense life story mostly set in Margate, the place where she grew up, containing a disturbing streak of sexual abjection, but at the same time presented with passion and strong irony.

The piece Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-95 brought Tracey Emin to fame. The peice is a now infamous embroidered tent with the appliquéd names of 102 people she had ever slept with, including friends, family, lovers, drinking partners and two numbered fetuses. This work was owned by Charles Saatchi and was destroyed in Momart London warehouse fire in 2004. Emin's next art work that raised attention was My Bed, shown at Tate Gallery as one of the shortlisted works for the Turner prize in 1999. Here, she exhibited her own bed covered with objects and traces of her struggle with depression during relationship difficulties, generating strong media attention due to the presence of bodily fluids on the sheets, as well as many everyday objects such as used condoms, empty bottles and slippers on the floor.

Tracey Emin can be considered one of the few artists able to reveal the intimate details of their life in an extremely powerful and honest way. The predominant subjects in her art are violent sex, motherhood, abortion, her hometown, family, lack of schooling, sexual past, as well as her affinity to alcohol. Tracey Emin's art presents the world of her hopes, failures, success and humiliations that contains both tragic and humorous elements. Nevertheless, her storytelling in various forms has the ability to avoid sentimentality and establishes an intimate connection with the viewers, engaging them with the unrestricted exploration of universal emotions. The power of Tracey Emin's art is in the ability to reveal the world in ways we have always known about but never admitted, exposing her own struggle to reach herself, to deconstruct her own celebrity status and her never-ending search for the strength needed to start all over again. Tracey Emin wrote a column for The Independent from 2008 - 2009 where many details of her unique life experience can be discerned. She also wrote the autobiographical book, Strangeland.

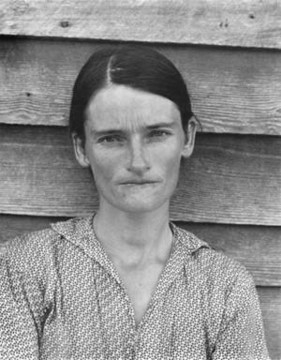

Sherrie Levine, (born April 17, 1947, Hazelton, Pa., U.S.), American conceptual artist known for remaking famous 20th-century works of art either through photographic reproductions (termed re-photography), drawing, watercolour, or sculpture. Her appropriations are conceptual gestures that question the Modernist myths of originality and authenticity. She held that the loss of authenticity in art was a result of the ubiquitous mediated signs that defined contemporary reality and that it was impossible to create anything new.

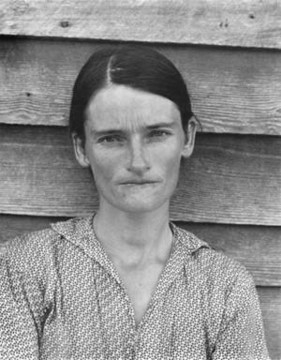

Levine grew up in the Midwest and attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison (B.A., 1969; M.F.A., 1973). She moved to New York City in 1975, and her earliest work-in collage-demonstrated a strong feminist leaning. In the early 1980s she began to be associated with a group of artists, including Jeff Koons and David Salle, who were interested in ready-made images and objects, and her work was included in some of the important early shows for this group. She began making photographic reproductions of images by such important American photographers as Edward Weston and Walker Evans, among others. She made drawings after such artists as Willem de Kooning, Egon Schiele, and Kazimir Malevich and watercolours after Piet Mondrian, Henri Matisse, and Fernand Léger. She deliberately chose artists with radically different styles, rendering them in a uniform format and thereby reducing the images to equivalent signs. In the mid-1980s she made two series of paintings based on the wood knot and the grid, provoking questions about the supposed unique style of modern abstraction. Her later works include reproductions of works by two major 20th-century artists: Marcel Duchamp’s famous ready-made Fountain and Constantin Brancusi’s Newborn. Keeping faith with her earliest feminist concerns, Levine appropriated only the work of male artists as a means of “de-heroicizing” their patriarchal claim to the art historical canon.

Self-portrait w added facial hair

A single shot of an abandoned beach at low tide in jumpy, color super-8 film, Ana Mendieta’s "Bird Run" (1974) has a wistful quality of emptiness for most of its silent two-minute duration. A small white figure is barely visible along the horizon as the water gently laps at the sand and the low grasses sway in the wind until, in a flash, a naked woman covered from head to toe in white feathers runs towards the camera, across the screen, and then vanishes as the film loops to the beginning. The presence of the bird-woman is fleeting: watching the film over and over, I strained to get a better look at this mysterious body, frustrated by its elusiveness, trying not to blink as she ran by. It is this flickering between presence and absence that characterizes the best work in Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance, the first large retrospective of Mendieta’s hybrid, yet truncated oeuvre.

Ana Mendieta has become something of an art world myth. Born in Cuba in 1948, but exiled to the United States as a child, she is the beautiful young multicultural woman artist working with ideas and forms of gender and culture in the heyday of feminist art and identity politics. She is also the beautiful young woman artist whose life ended mysteriously one night after a violent fight with her lover, the older and more established artist Carl Andre, as she fell to her death from the thirty-fourth floor window of their SoHo loft in 1985 (Andre was subsequently tried for her murder and ultimately acquitted). The particular details of her biography make Mendieta a tragically romantic figure and it is tempting to read her work through her life as her image reappears over and over within her work, a haunting reminder of her life and death. This problem is not unique: Francesca Woodman, Hannah Wilke, Diane Arbus, Eva Hesse, the list of women artists whose tragic biographies tend to overshadow their work is long. That Mendieta, like Woodman and Wilke, used her own body as an instrumental part of her artistic practice makes the distance between art and life appear to shrink even further. Although the current exhibition includes and sometimes highlights the details of her biography, it also allows for an unprecedented consideration of Mendieta’s art, fragmentary, stunning, and uneven as it is.

The earliest work at the Whitney dates to Mendieta’s time as a graduate student in painting at the University of Iowa where she was profoundly influenced by the dynamic avant-garde community and the rolling hills of the Iowa landscape. In 1969, her first year of graduate school, she began a decade-long affair with the artist Hans Breder, who founded the Intermedia program at Iowa, a special interdisciplinary arts program in which Mendieta studied and taught. The pieces from this period are truly inter-media, combining performance, photography and film, and conceptual art, without any genre taking precedence as the art object. In the series of headshots dubbed Untitled (Facial Cosmetic Variations) (1972), Mendieta grotesquely transforms her visage with stockings pulled over her head, torn in different places, caked on makeup, wigs, and distorted expressions; while the related series Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants) (1972) documents the transfer of fellow student Morty Sklar’s beard to Mendieta’s face. Although Mendieta appears in both projects, two of very few works in which her face is visible, she is not revealed in any traditional sense of a self-portrait. Rather these two works highlight indeterminacy-in individual identity and in the fluidity of artistic media-with a deadpan tone that verges on the absurd. The mocking film "Door Piece" (1973) limits vision to the gaze through a keyhole, an overly literal enactment of early feminist criticism of "the gaze" that ends in a humorous close-up of Mendieta rimming the peephole with her tongue. An odd and funny homage to Duchamp, the film casts the viewer into the space on the inside of the peephole of "Etant Donnés," limiting the viewer’s field of vision, and turning her into the object of the film’s blind gaze.

If Mendieta plays with vision and surface in these early works, she also explores physical and material transformations through body-based works. ....

But violence also fascinated Mendieta. The dark scene in an 8×10 color photograph dated 1973 offers an almost matter-of-fact crime scene image: harsh spotlight illuminates an impoverished apartment with broken dishes on the floor and a decrepit wooden table, with the artist’s body bent at a right angle away from the camera, ass in the air, covered in blood dripping down her bare legs and pooling in the white panties around her ankles, head invisible in the shadows. "Untitled (Rape Scene)" (1973) is the record of a performance/ installation Mendieta created in her apartment in Iowa to recreate the scene of a real violent rape-murder of a young woman that March that had been reported in detail in the press. Although the image immediately suggests a feminist politics, a statement against violence against women, when coupled with the series of slides shown in a vitrine nearby of Untitled (People Looking at Blood, Moffit) (1973), rows of mundane street shots of ordinary passersby in front of a doorway where Mendieta spread animal blood, the effect is not a condemnation of violence, but a sense of detachment and displacement. The absence of causality in these images, the implication of violence but never its depiction, works to displace the viewer’s ability to comprehend each scene as a narrative; rather the images seem to challenge the viewer, to heighten a sense of dislocation, mediating any sense of transparency in Mendieta’s use of her own body in the work. These are images are some of the most tempting to read biographically given the intimate violence that lead to Mendieta’s death, yet it is precisely in these images that the artist refuses that paradigm: her defiant stare in "Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood)" (1973), bloodied face filling the frame is one of the most powerful in the show.

....

The Siluetas are the quintessential "Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance" referred to in the exhibition’s title, which belies the complexity of Mendieta’s relationship to land art. While the comparison to Smithson and Heizer is certainly historically appropriate, the Siluetas have a quality similar to Richard Long’s and Andy Goldsworthy’s ephemeral natural sculptures: both artists build forms out of natural materials in the landscape without permanently transforming the environment, but "fixing" these delicate, ephemeral impressions with photography. Rather than altering the landscape in the usual sense implied by the categories "earthworks" and "land art," Mendieta’s work at its best centers on the sensations of landscape, the physical experience of the world through natural elements that shapes, transforms, and even erases identity.

As the Siluetas progress, their forms spin further and further from the outline of Mendieta’s petite figure into round primitivized goddess forms. With bulging hips and arms raised like tree branches, her cipher reappears in the leaf drawings, tree and twig sculptures, and Rupestrian Sculptures carved in the Cuban landscape and documented in large black-and-white photographs, creating a prehistoric, fossilized quality through iconography and materials. While the resulting images register the trace of Mendieta’s hand, the forms themselves are not the indices of the early Siluetas, but rather symbols for a generic earth goddess. The catalogue includes exhaustive discussion of the various sources of this imagery, and while Mendieta’s references were vast, the images themselves lack the personal force of her earlier work. Aggressively pursuing grants and gallery representation after leaving the seminal feminist collective A.I.R. Gallery in 1982, Mendieta’s interest in creating lasting objects that could be sold is obvious. The growing force of identity politics and postmodernism in the 1980s is also manifest in these later sculptures that fixate on subject matter-femininity, fertility, death and rebirth-rather than the processes of earlier intermedia projects that foregrounded experience rather than issues. At the time of her death, Mendieta was exploring one set of possibilities suggested by her early work. Although it is pointless to speculate about what might have been, Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance presents the gorgeous fragments and sketches of those possibilities. At its best, Mendieta’s work has a quality of displacement and longing, of indeterminacy and potentiality, which transcends identity politics and opens up the possibility of intimacy in a vast landscape.

Yayoi Kusama is one of the most influential and widely-collected artists of the 1960s and quite possibly Japan's premiere artist of the modern era. Critics have variously ascribed her work to minimalism, feminism, obsessivism, surrealism, pop, and abstract expressionism. One thing for certain is that it has been a long and strange journey for Kusama, who is 74 in 2004.

Born in Matsumoto in 1929, Kusama remembers growing up "as an unwanted child of unloving parents." A penchant for drawing and painting led Kusama to plot her escape with the help of art magazines, and after sewing black-market American currency into the seams of her clothes, Kusama fled Japan in search of her hero, Georgia O'Keeffe.

She arrived in New York in 1958 and began to create a life for herself as an artist. Kusama made the front page of the New York Daily News in August, 1969, after infiltrating the Museum of Modern Art's sculpture garden with a bunch of naked co-conspirators to perform her "Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead."

Kusama's paintings, collages, sculptures, and environmental works all share an obsession with repetition, pattern, and accumulation. Hoptman writes that "Kusama's interest in pattern began with hallucinations she experienced as a young girl--visions of nets, dots, and flowers that covered everything she saw. Gripped by the idea of 'obliterating the world,' she began covering larger and larger areas of canvas with patterns." Her organically abstract paintings of one or two colors (the Infinity Netsseries), which she began upon arriving in New York, garnered comparisons to the work of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman.

In Kusama's sculptures, the obsessive quality of the webs in her paintings is expressed in three dimensions. Household furniture, women's clothes, and high-heeled shoes are covered in bristling fields of fiber-stuffed phallic forms painted monochrome white, silver, or bronze. Other objects are covered in macaroni pasta and painted gold; mannequins are painted with colorful nets and polka-dots.

In the late 1970s, as Kusama stretched her vision further toward infinity by building ambitious mirror-room installations, she got lost somewhere along the way, and ended up back in Japan, at a Tokyo psychiatric hospital, in the small room where she stayed for over 20 years. Kusama learned during this time that the act of creation could also be a weapon in the battle against her mental illness, "If I didn?t make art," she is widely quoted as saying, "I'd probably be dead by now." She continued to work every day, returning to the hospital room only to eat and sleep because, she says, her life became easiest that way.

In the 1980s Kusama had solo shows of her work in France, New York, and London. In 1993 she was invited to the 45th Venice Biennale in Italy. She was invited to make permanent public art sculpture in Japan and Spain. Kusama had a major retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum and traveled to New York and Japan.

Sources: Kathe Kollwitz, Tracey Emin, Sherrie Levine, Ana Mendieta, and Yayoi Kusama

Today, we will be covering these five brilliant women:

Käthe Kollwitz was born July 8, 1867 in Kaliningrad, Russia. She devoted herself primarily to graphic art after 1890. Her first important works were two separate series of prints, Weavers' Revolt and Peasants' War. The death of her youngest in 1914 led to another cycle of prints of a mother protecting her children. Her last great series of lithographs was Death.

The artist grew up in a liberal middle-class family and studied painting in Berlin (1884-85) and Munich (1888-89). Impressed by the prints of Max Klinger, she devoted herself primarily to graphic art after 1890, producing etchings, lithographs, woodcuts, and drawings. In 1891 she married Karl Kollwitz, a doctor who opened a clinic in a working-class section of Berlin. There she gained firsthand insight into the miserable conditions of the urban poor.

Kollwitz's first important works were two separate series of prints, respectively entitled Weavers' Revolt (c. 1894-98) and Peasants' War (1902-08). In these works she portrayed the plight of the poor and oppressed with the powerfully simplified, boldly accentuated forms that became her trademark. The death of her youngest son in battle in 1914 profoundly affected her, and she expressed her grief in another cycle of prints that treat the themes of a mother protecting her children, and of a mother with a dead child. From 1924 to 1932 Kollwitz also worked on a granite monument for her son, which depicted her husband and herself as grieving parents. In 1932 it was erected as a memorial in a cemetery near Ypres, Belgium.

Kollwitz greeted the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the German revolution of 1918 with hope, but she eventually became disillusioned with Soviet communism. During the years of the Weimar Republic, she became the first woman to be elected a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts, where from 1928 to 1933 she was head of the Master Studio for Graphic Arts. Kollwitz continued to devote herself to socially effective, easily understood art. The Nazis' rise to power in Germany in 1933 led to her forced resignation from the academy.

Kollwitz's last great series of lithographs, Death (1934-36), treats that tragic theme with stark and monumental forms that convey a sense of drama. In 1940 her husband died, and in 1942 her grandson was killed in action during World War II. The bombing of Kollwitz's home and studio in 1943 destroyed much of her life's work. She died a few weeks before the end of the war in Europe. Kollwitz was the last great practitioner of German Expressionism and is often considered to be the foremost artist of social protest in the 20th century. The Diary and Letters of Kaethe Kollwitz was published in 1988.

Tracey Emin, Ph.D., was born in Croydon, England on July 3, 1963. She was a Professor of Confessional Art at the European Graduate School (EGS) where she gave a guest lecture. A London-based artist, Tracey Emin has been recognized as one of the leading figures of the YBA (Young British Artists) in the 1990s. She graduated in fine arts from the Maidstone College of Art in 1986, and was awarded an MA in painting by the Royal College of Art in 1989. Tracey Emin also studied modern philosophy in London and was on the short list for the Turner Prize in 1999. She has exhibited extensively internationally, with solo shows at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Modern Art Oxford, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Platform Garanti Contemporary Art Center, Istanbul, and Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Tracey Emin represented Britain at the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007. In the same year, she was made a Royal Academician and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the Royal College of Art, London, a Doctor of Philosophy from London Metropolitan University and Doctor of Letters from the University of Kent.

Tracey Emin's works are known for their immediacy, raw openness and often sexually provocative attitude which fascinates the viewer. Her art is deeply confessional and she herself has become the embodiment of the artist as a maverick, even outsider celebrity, constantly infuriating the art world and provoking the British class system with her open working-class attitude. Named by David Bowie to be 'William Blake as a woman, written by Mike Leigh', her public persona is loud, dangerous and unpredictable, but at the same time radiates a deeply emotional and vulnerable side. Her controlled exhibition of the self takes a form in exceptionally wide range of media - from appliquéd blankets and sewing, to neons, videos, super-8 films, photographs, animations, watercolors, sculptures, installations, and intensely personal paintings and drawings. One of the aspects of Tracey Emin's work unfairly receiving little attention is her writing - here, she pushes the borders between writing as visual art and visual art as a text, forcing us to rethink the status of both.

Roberta Smith of The New Yorker says the following about Tracey’s work:

"If Tracey Emin could sing, she might be Judy Garland, a bundle of irresistible, pathetic, ferocious, self-indulgent, brilliant energy. Since she can't, or doesn't, she writes, incorporating autobiographical texts and statements into drawings, monoprints, watercolors, collages, quilts, neon sculptures, installations and videotapes. In her art she tells all, all the truths, both awful and wonderful, but mostly awful, about her life. Physical and psychic pain in the form of rejection, incest, rape, abortion and sex with strangers figure in this tale, as do love, passion and joy."

After a difficult childhood, Tracey Emin squatted in London after dropping out of school at thirteen. This period of her life provided a strong inspiration for much of her later work. She studied art in Essex and London, deciding to destroy all her work after a traumatic abortion in 1989. She began working only several years later, reworking her past by producing confessional letters and combining them with mementos from her youth. Tracey Emin presented this material at her first solo exhibition at the White Cube Gallery in London in 1993, provocatively entitled 'My Major Retrospective'. The show told her intense life story mostly set in Margate, the place where she grew up, containing a disturbing streak of sexual abjection, but at the same time presented with passion and strong irony.

The piece Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-95 brought Tracey Emin to fame. The peice is a now infamous embroidered tent with the appliquéd names of 102 people she had ever slept with, including friends, family, lovers, drinking partners and two numbered fetuses. This work was owned by Charles Saatchi and was destroyed in Momart London warehouse fire in 2004. Emin's next art work that raised attention was My Bed, shown at Tate Gallery as one of the shortlisted works for the Turner prize in 1999. Here, she exhibited her own bed covered with objects and traces of her struggle with depression during relationship difficulties, generating strong media attention due to the presence of bodily fluids on the sheets, as well as many everyday objects such as used condoms, empty bottles and slippers on the floor.

Tracey Emin can be considered one of the few artists able to reveal the intimate details of their life in an extremely powerful and honest way. The predominant subjects in her art are violent sex, motherhood, abortion, her hometown, family, lack of schooling, sexual past, as well as her affinity to alcohol. Tracey Emin's art presents the world of her hopes, failures, success and humiliations that contains both tragic and humorous elements. Nevertheless, her storytelling in various forms has the ability to avoid sentimentality and establishes an intimate connection with the viewers, engaging them with the unrestricted exploration of universal emotions. The power of Tracey Emin's art is in the ability to reveal the world in ways we have always known about but never admitted, exposing her own struggle to reach herself, to deconstruct her own celebrity status and her never-ending search for the strength needed to start all over again. Tracey Emin wrote a column for The Independent from 2008 - 2009 where many details of her unique life experience can be discerned. She also wrote the autobiographical book, Strangeland.

Sherrie Levine, (born April 17, 1947, Hazelton, Pa., U.S.), American conceptual artist known for remaking famous 20th-century works of art either through photographic reproductions (termed re-photography), drawing, watercolour, or sculpture. Her appropriations are conceptual gestures that question the Modernist myths of originality and authenticity. She held that the loss of authenticity in art was a result of the ubiquitous mediated signs that defined contemporary reality and that it was impossible to create anything new.

Levine grew up in the Midwest and attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison (B.A., 1969; M.F.A., 1973). She moved to New York City in 1975, and her earliest work-in collage-demonstrated a strong feminist leaning. In the early 1980s she began to be associated with a group of artists, including Jeff Koons and David Salle, who were interested in ready-made images and objects, and her work was included in some of the important early shows for this group. She began making photographic reproductions of images by such important American photographers as Edward Weston and Walker Evans, among others. She made drawings after such artists as Willem de Kooning, Egon Schiele, and Kazimir Malevich and watercolours after Piet Mondrian, Henri Matisse, and Fernand Léger. She deliberately chose artists with radically different styles, rendering them in a uniform format and thereby reducing the images to equivalent signs. In the mid-1980s she made two series of paintings based on the wood knot and the grid, provoking questions about the supposed unique style of modern abstraction. Her later works include reproductions of works by two major 20th-century artists: Marcel Duchamp’s famous ready-made Fountain and Constantin Brancusi’s Newborn. Keeping faith with her earliest feminist concerns, Levine appropriated only the work of male artists as a means of “de-heroicizing” their patriarchal claim to the art historical canon.

Self-portrait w added facial hair

A single shot of an abandoned beach at low tide in jumpy, color super-8 film, Ana Mendieta’s "Bird Run" (1974) has a wistful quality of emptiness for most of its silent two-minute duration. A small white figure is barely visible along the horizon as the water gently laps at the sand and the low grasses sway in the wind until, in a flash, a naked woman covered from head to toe in white feathers runs towards the camera, across the screen, and then vanishes as the film loops to the beginning. The presence of the bird-woman is fleeting: watching the film over and over, I strained to get a better look at this mysterious body, frustrated by its elusiveness, trying not to blink as she ran by. It is this flickering between presence and absence that characterizes the best work in Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance, the first large retrospective of Mendieta’s hybrid, yet truncated oeuvre.

Ana Mendieta has become something of an art world myth. Born in Cuba in 1948, but exiled to the United States as a child, she is the beautiful young multicultural woman artist working with ideas and forms of gender and culture in the heyday of feminist art and identity politics. She is also the beautiful young woman artist whose life ended mysteriously one night after a violent fight with her lover, the older and more established artist Carl Andre, as she fell to her death from the thirty-fourth floor window of their SoHo loft in 1985 (Andre was subsequently tried for her murder and ultimately acquitted). The particular details of her biography make Mendieta a tragically romantic figure and it is tempting to read her work through her life as her image reappears over and over within her work, a haunting reminder of her life and death. This problem is not unique: Francesca Woodman, Hannah Wilke, Diane Arbus, Eva Hesse, the list of women artists whose tragic biographies tend to overshadow their work is long. That Mendieta, like Woodman and Wilke, used her own body as an instrumental part of her artistic practice makes the distance between art and life appear to shrink even further. Although the current exhibition includes and sometimes highlights the details of her biography, it also allows for an unprecedented consideration of Mendieta’s art, fragmentary, stunning, and uneven as it is.

The earliest work at the Whitney dates to Mendieta’s time as a graduate student in painting at the University of Iowa where she was profoundly influenced by the dynamic avant-garde community and the rolling hills of the Iowa landscape. In 1969, her first year of graduate school, she began a decade-long affair with the artist Hans Breder, who founded the Intermedia program at Iowa, a special interdisciplinary arts program in which Mendieta studied and taught. The pieces from this period are truly inter-media, combining performance, photography and film, and conceptual art, without any genre taking precedence as the art object. In the series of headshots dubbed Untitled (Facial Cosmetic Variations) (1972), Mendieta grotesquely transforms her visage with stockings pulled over her head, torn in different places, caked on makeup, wigs, and distorted expressions; while the related series Untitled (Facial Hair Transplants) (1972) documents the transfer of fellow student Morty Sklar’s beard to Mendieta’s face. Although Mendieta appears in both projects, two of very few works in which her face is visible, she is not revealed in any traditional sense of a self-portrait. Rather these two works highlight indeterminacy-in individual identity and in the fluidity of artistic media-with a deadpan tone that verges on the absurd. The mocking film "Door Piece" (1973) limits vision to the gaze through a keyhole, an overly literal enactment of early feminist criticism of "the gaze" that ends in a humorous close-up of Mendieta rimming the peephole with her tongue. An odd and funny homage to Duchamp, the film casts the viewer into the space on the inside of the peephole of "Etant Donnés," limiting the viewer’s field of vision, and turning her into the object of the film’s blind gaze.

If Mendieta plays with vision and surface in these early works, she also explores physical and material transformations through body-based works. ....

But violence also fascinated Mendieta. The dark scene in an 8×10 color photograph dated 1973 offers an almost matter-of-fact crime scene image: harsh spotlight illuminates an impoverished apartment with broken dishes on the floor and a decrepit wooden table, with the artist’s body bent at a right angle away from the camera, ass in the air, covered in blood dripping down her bare legs and pooling in the white panties around her ankles, head invisible in the shadows. "Untitled (Rape Scene)" (1973) is the record of a performance/ installation Mendieta created in her apartment in Iowa to recreate the scene of a real violent rape-murder of a young woman that March that had been reported in detail in the press. Although the image immediately suggests a feminist politics, a statement against violence against women, when coupled with the series of slides shown in a vitrine nearby of Untitled (People Looking at Blood, Moffit) (1973), rows of mundane street shots of ordinary passersby in front of a doorway where Mendieta spread animal blood, the effect is not a condemnation of violence, but a sense of detachment and displacement. The absence of causality in these images, the implication of violence but never its depiction, works to displace the viewer’s ability to comprehend each scene as a narrative; rather the images seem to challenge the viewer, to heighten a sense of dislocation, mediating any sense of transparency in Mendieta’s use of her own body in the work. These are images are some of the most tempting to read biographically given the intimate violence that lead to Mendieta’s death, yet it is precisely in these images that the artist refuses that paradigm: her defiant stare in "Untitled (Self-Portrait with Blood)" (1973), bloodied face filling the frame is one of the most powerful in the show.

....

The Siluetas are the quintessential "Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance" referred to in the exhibition’s title, which belies the complexity of Mendieta’s relationship to land art. While the comparison to Smithson and Heizer is certainly historically appropriate, the Siluetas have a quality similar to Richard Long’s and Andy Goldsworthy’s ephemeral natural sculptures: both artists build forms out of natural materials in the landscape without permanently transforming the environment, but "fixing" these delicate, ephemeral impressions with photography. Rather than altering the landscape in the usual sense implied by the categories "earthworks" and "land art," Mendieta’s work at its best centers on the sensations of landscape, the physical experience of the world through natural elements that shapes, transforms, and even erases identity.

As the Siluetas progress, their forms spin further and further from the outline of Mendieta’s petite figure into round primitivized goddess forms. With bulging hips and arms raised like tree branches, her cipher reappears in the leaf drawings, tree and twig sculptures, and Rupestrian Sculptures carved in the Cuban landscape and documented in large black-and-white photographs, creating a prehistoric, fossilized quality through iconography and materials. While the resulting images register the trace of Mendieta’s hand, the forms themselves are not the indices of the early Siluetas, but rather symbols for a generic earth goddess. The catalogue includes exhaustive discussion of the various sources of this imagery, and while Mendieta’s references were vast, the images themselves lack the personal force of her earlier work. Aggressively pursuing grants and gallery representation after leaving the seminal feminist collective A.I.R. Gallery in 1982, Mendieta’s interest in creating lasting objects that could be sold is obvious. The growing force of identity politics and postmodernism in the 1980s is also manifest in these later sculptures that fixate on subject matter-femininity, fertility, death and rebirth-rather than the processes of earlier intermedia projects that foregrounded experience rather than issues. At the time of her death, Mendieta was exploring one set of possibilities suggested by her early work. Although it is pointless to speculate about what might have been, Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance presents the gorgeous fragments and sketches of those possibilities. At its best, Mendieta’s work has a quality of displacement and longing, of indeterminacy and potentiality, which transcends identity politics and opens up the possibility of intimacy in a vast landscape.

Yayoi Kusama is one of the most influential and widely-collected artists of the 1960s and quite possibly Japan's premiere artist of the modern era. Critics have variously ascribed her work to minimalism, feminism, obsessivism, surrealism, pop, and abstract expressionism. One thing for certain is that it has been a long and strange journey for Kusama, who is 74 in 2004.

Born in Matsumoto in 1929, Kusama remembers growing up "as an unwanted child of unloving parents." A penchant for drawing and painting led Kusama to plot her escape with the help of art magazines, and after sewing black-market American currency into the seams of her clothes, Kusama fled Japan in search of her hero, Georgia O'Keeffe.

She arrived in New York in 1958 and began to create a life for herself as an artist. Kusama made the front page of the New York Daily News in August, 1969, after infiltrating the Museum of Modern Art's sculpture garden with a bunch of naked co-conspirators to perform her "Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead."

Kusama's paintings, collages, sculptures, and environmental works all share an obsession with repetition, pattern, and accumulation. Hoptman writes that "Kusama's interest in pattern began with hallucinations she experienced as a young girl--visions of nets, dots, and flowers that covered everything she saw. Gripped by the idea of 'obliterating the world,' she began covering larger and larger areas of canvas with patterns." Her organically abstract paintings of one or two colors (the Infinity Netsseries), which she began upon arriving in New York, garnered comparisons to the work of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman.

In Kusama's sculptures, the obsessive quality of the webs in her paintings is expressed in three dimensions. Household furniture, women's clothes, and high-heeled shoes are covered in bristling fields of fiber-stuffed phallic forms painted monochrome white, silver, or bronze. Other objects are covered in macaroni pasta and painted gold; mannequins are painted with colorful nets and polka-dots.

In the late 1970s, as Kusama stretched her vision further toward infinity by building ambitious mirror-room installations, she got lost somewhere along the way, and ended up back in Japan, at a Tokyo psychiatric hospital, in the small room where she stayed for over 20 years. Kusama learned during this time that the act of creation could also be a weapon in the battle against her mental illness, "If I didn?t make art," she is widely quoted as saying, "I'd probably be dead by now." She continued to work every day, returning to the hospital room only to eat and sleep because, she says, her life became easiest that way.

In the 1980s Kusama had solo shows of her work in France, New York, and London. In 1993 she was invited to the 45th Venice Biennale in Italy. She was invited to make permanent public art sculpture in Japan and Spain. Kusama had a major retrospective at the Los Angeles County Museum and traveled to New York and Japan.

Sources: Kathe Kollwitz, Tracey Emin, Sherrie Levine, Ana Mendieta, and Yayoi Kusama