Women's HERstory Month Day Fifteen: 20 Women Artists to Know (Part 1)

As an art student and art history major, women in art history are a very important topic to my own life. So here, with various sources, are the first 5 of 20 women artists I think everyone should have passing familiarity with. Of course, additions to the list in the comments are always more than welcome! These are in no particular order.

This will be image heavy due to the nature of the post. Also slightly nsfw because art.

Ghadar Amer (born in 1963) is an Egyptian artist.

Ghada Amer was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1963, studied painting and fine arts in Nice, Boston, and Paris, and has been exhibiting her works since the early 1990s. From the very beginning of her career, Amer has been engaged in an investigation of the stereotypical notions, images, and techniques of femininity, as they are played out both in the visual arts and in everyday life. She lives and works in New York.

Embroidery, stitching, and sewing, traditionally identified as “female” techniques, have since become trademarks of Amer’s work, and have been used repeatedly by feminist artists since the 1960s as an ironic or subversive commentary on the male dominated techniques of painting and sculpture, especially as the heroic traditions of Abstract Expressionism and Monumental Sculpture.

Amer’s engagement with definitions and descriptions of femininity, as well as the continuous loosening of her embroideries towards more soft, tactile, and abstract surfaces, shifted increasingly toward other fields of reference. In “Counseils de Beauté” (Beauty Tips, 1993), Amer ironically embroidered several texts that give standard advice on the difficult task of keeping up personal hygiene. Other descriptions of beauty, femininity, and corporeality also find entrance into Amer’s work when she reproduces erotic stories and descriptions from both the Western canon of literature and Arabic cultural heritage. For example, the work “Private Rooms” (1997) features quotations from erotic narratives in the Ku’ran embroidered onto large canvas screens, and the work “Encyclopedy of Pleasures” (2001) features a series of cloth covered boxes embroidered with descriptions of all varieties of human eroticism found in Muslim medieval manuscripts.

She and fellow Muslim artist Ladan Naderi too this photo in protest of France's burqa fan.

Since the mid 1990s, Amer has also incorporated more direct images of sexuality into her richly textured canvases. Amer often uses images of women in explicit sexual poses, copied from softcore pornographic magazines, reproducing a selected image repetitiously across the canvas. Here she recalls another technique from the history of embroidery, namely patterning, the repetition of a selected image also results in the blurring of the image, as if to render it mute or abstract. At the same time, Amer has begun to color her canvases, pouring and blotching paint over parts of the painting before embroidering into it. By taking on methods of painting that were first introduced and canonized by Abstract Expressionism and combining them with the repetitious embroidery of pornographic images, Amer has arrived at a more openly pronounced criticism of (stereotypically) male artistic behavior. With Abstract Expressionism as the common point of reference for heroic artistic gestures and the sexist visualness of pornographic magazines as the definitive example of the male gaze, Amer has isolated two dominant strands in popular visual culture. By combining these with the subtle textuality of her intertwined threads, colored blotches and soft objects, Amer manages to continue her quiet critique of the stereotypes of domesticity, femininity, and sexuality, while simultaneously embracing the contested imagery. The slightly disconcerting feeling of unrest that often comes with her work thus can be seen as proof of the constant rejection of simple visual or thematic solutions to the questions Amer’s work has been asking for over a decade.

Born Diane Nemerov on March 14, 1923, in New York, New York. Diane Arbus was one of the most distinctive photographers in the twentieth century, known for her eerie portraits and offbeat subjects. Her artistic talents emerged at a young age; she was created interesting drawings and paintings while in high school. She married Allan Arbus in 1941 who taught her photography.

Working with her husband, Diane Arbus started out in advertising and fashion photography. They became quite a successful team with photographs appearing in such magazines as Vogue. In the late 1950s, she began to focus on her own photography. To further her art, Arbus studied with photographer Lisette Model around this time. She began to pursue taking photographs of people she found during her wanderings around New York City. She visited seedy hotels, public parks, a morgue, and other various locales. These unusual images had a raw quality and several of them found their way in the July 1960 issue of Esquire magazine. These photographs were a spring board for more work for Arbus.

By the mid-1960s, Diane Arbus was a well-established photographer, participating in shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York among other places. She was known for going to great lengths to get the shots she wanted. She became friends with many other famous photographers, such as Richard Avedon and Walker Evans.

While professionally Arbus continued to thrive in the late 1960s, she had some personal challenges. Her marriage ended in 1969, and she later struggled with depression. She committed suicide in her New York apartment on July 26, 1971. Her work remains a subject of intense interest, and her life was part of the basis of the 2006 film, Fur, starring Nicole Kidman as Arbus.

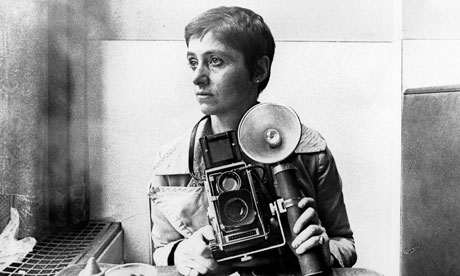

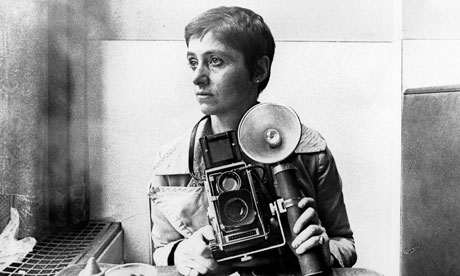

Self portrait

Artemisia Gentileschi was the most important woman painter of Early Modern Europe by virtue of the excellence of her work, the originality of her treatment of traditional subjects, and the number of her paintings that have survived (though only thirty-four of a much larger corpus remain, many of them only recently attributed to her rather than to her male contemporaries). She was both praised and disdained by contemporary critical opinion, recognized as having genius, yet seen as monstrous because she was a woman exercising a creative talent thought to be exclusively male. Since then, in the words of Mary D. Garrard, she "has suffered a scholarly neglect that is almost unthinkable for an artist of her caliber."

Like many other women artists of her era who were excluded from apprenticeship in the studios of successful artists, Gentileschi was the daughter of a painter. She was born in Rome on July 8, 1593, the daughter of Orazio and Prudentia Monotone Gentileschi. Her mother died when Artemisia was twelve. Her father trained her as an artist and introduced her to the working artists of Rome, including Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose chiaroscuro style (contrast of light and shadow) greatly influenced Artemisia Gentileschi's work. Other than artistic training, she had little or no schooling; she did not learn to read and write until she was adult. However, by the time she was seventeen, she had produced one of the works for which she is best known, her stunning interpretation of Susanna and the Elders (1610).

Among those with whom Orazio Gentileschi worked was the Florentine artist Agostino Tassi, whom Artemisia accused of raping her in 1612, when she was nineteen. Her father filed suit against Tassi for injury and damage, and, remarkably, the transcripts of the seven-month-long rape trial have survived. According to Artemisia, Tassi, with the help of family friends, attempted to be alone with her repeatedly, and raped her when he finally succeeded in cornering her in her bedroom. He tried to placate her afterwards by promising to marry her, and gained access to her bedroom (and her person) repeatedly on the strength of that promise, but always avoided following through with the actual marriage. The trial followed a pattern familiar even today: she was accused of not having been a virgin at the time of the rape and of having many lovers, and she was examined by midwives to determine whether she had been "deflowered" recently or a long time ago.

Perhaps more galling for an artist like Gentileschi, Tassi testified that her skills were so pitiful that he had to teach her the rules of perspective, and was doing so the day she claimed he raped her. Tassi denied ever having had sexual relations with Gentileschi and brought many witnesses to testify that she was "an insatiable whore." Their testimony was refuted by Orazio (who brought countersuit for perjury), and Artemisia's accusations against Tassi were corroborated by a former friend of his who recounted Tassi's boasting about his sexual exploits at Artemisia's expense. Tassi had been imprisoned earlier for incest with his sister-in-law and was charged with arranging the murder of his wife. He was ultimately convicted on the charge of raping Gentileschi; he served under a year in prison and was later invited again into the Gentileschi household by Orazio.

Artemisia's reputation was ruined by the publicity of the trial, one of the many reasons she is not often mentioned in art history then or today.

Self portrait

Mary Cassatt was born in 1844 in Pennsylvania, USA as the daughter of a wealthy merchant. At the age of seven her family left for Paris in France. After a few years of life in Paris, the family went back to the USA. Mary, impressed by all the art she had seen in Europe, surprised her parents by the wish to become an artist. Becoming an artist in the 19th century was as difficult for a woman as becoming a doctor. Society then had a different understanding of the role of women.

Finally Mary won and her parents allowed her to visit the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1866 she went back to Paris. She copied the old masters in the Louvre and other museums. The young woman artist had acquired pretty good skills in traditional art style and in 1872 a Mary Cassatt painting was even accepted by the judges of the Salon.

Then she got to know Edgar Degas, an artist from the group of Impressionists who were refused by the Salon and had established their own show, the Salon des Refuses. Edgar Degas introduced her to his friends Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro and other Impressionist rebels.

Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas became good friends. Some art historians think she also was his mistress. This is however rather questionable as Degas was considered a convinced misogynist. Under the influence of Edgar Degas and the other Impressionists the artist Mary Cassatt changed her painting style. She used light colors and began to paint people.

Mary Cassatt's favorite subjects became children and women with children in ordinary scenes. Her paintings express a deep tenderness and her own love for children. But she never had children of her own.

The artist's artistic breakthrough came in 1892, when she received a commission for a mural for the Woman's Building at the Chicago World's Fair. The mural painting got lost after the fair and has not shown up until today.

Mary Cassatt was also an excellent printmaker. After experimenting with different printmaking techniques like etching and aquatint she finally discovered drypoint combined with aquatint as her favorite intaglio process. Between 1889 and 1890 she created a set of twelve wonderful drypoints. From 1890 to 1891 she made a series of ten color prints, known as The Ten. This series is considered as a landmark in Impressionist printmaking. She continued to make prints until 1896.

Mary Cassatt prints show a strong influence of Japanese prints and later of Renaissance paintings.

Mary Cassatt influenced Impressionism not only as an artist. She also had an important role in sponsoring and in financial promotion of Impressionist art. She often bought paintings of her friends when they were short of cash. And with her connections to rich American families, she encouraged many of her countrymen to buy Impressionist art. Quite a few of the great Impressionist art collections in the USA were established as a result of her activities. The collection of 19th century French paintings of the Havemeyers was largely mediated by her. The collection is now in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The artist Mary Cassatt would have made a poor career as a diplomat. She never held back with her opinion. Fortunately her wealth made her independent from what others thought about her. Especially when she grew older, her frankness could sometimes become insulting.

She did not like the modern artists like Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso and spoke of "dreadful paintings". Even her Impressionist colleagues were whacked. For Claude Monet's late works - his famous water-lily paintings - she found the words "glorified wallpaper".

She had one thing in common with Edgar Degas and that was poor eyesight. When she died in 1926 at the age of 82 she was blind.

Self portrait

Born January 14, 1841, in Bourges, France, Berthe Morisot's father was a high-ranking government official and her grandfather was the influential Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. She and her sister Edma began painting as young girls. Despite the fact that as women they were not allowed to join official arts institutions, the sisters earned respect in art circles for their talent.

Berthe and Edma Morisot traveled to Paris to study and copy works by the Old Masters at the Louvre Museum in the late 1850s under Joseph Guichard. They also studied with landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot to learn how to paint outdoor scenes. Berthe Morisot worked with Corot for several years and first exhibited her work in the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, in 1864. She would earn a regular spot at show for the next decade.

In 1868, fellow artist Henri Fantin-Latour introduced Berthe Morisot to Edouard Manet. The two formed a lasting friendship and greatly influenced one another's work. Berthe soon eschewed the paintings of her past with Corot, migrating instead toward Manet's more unconventional and modern approach. She also befriended the Impressionists Edgar Degas and Frédéric Bazille and in 1874, refused to show her work at the Salon. She instead agreed to be in the first independent show of Impressionist paintings, which included works by Degas, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Alfred Sisley. (Manet declined to be included in the show, determined to find success at the official Salon.) Among the paintings Morisot showed at the exhibition were The Cradle, The Harbor at Cherbourg, Hide and Seek, and Reading.

In 1874, Berthe Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugne, also a painter. The marriage provided her with social and financial stability while she continued to pursue her painting career. Able to dedicate herself wholly to her craft, Morisot participated in the Impressionist exhibitions every year except 1877, when she was pregnant with her daughter.

Berthe Morisot portrayed a wide range of subjects-from landscapes and still lifes to domestic scenes and portraits. She also experimented with numerous media, including oils, watercolors, pastels, and drawings. Most notable among her works during this period is Woman at Her Toilette (c. 1879). Later works were more studied and less spontaneous, such as The Cherry Tree (1891-92) and Girl with a Greyhound (1893).

After her husband died in 1892, Berthe Morisot continued to paint, although she was never commercially successful during her lifetime. She did, however, outsell several of her fellow Impressionists, including Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. She had her first solo exhibition in 1892 and two years later the French government purchased her oil painting Young Woman in a Ball Gown. Berthe Morisot contracted pneumonia and died on March 2, 1895, at age 54.

Sources: Ghada Amer, Diane Arbus, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot

Upcoming: Kathe Kolwitz, Tracey Emin, Sherry Levine, Ana Mendieta, Yayoi Kusama, Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, Barbra Kurger, Remedios Varo, Frida Kahlo, Julie Mehretu, Yoko Ono, Lee Krasner, Marina Abramović and Alice Neel.

This will be image heavy due to the nature of the post. Also slightly nsfw because art.

Ghadar Amer (born in 1963) is an Egyptian artist.

Ghada Amer was born in Cairo, Egypt, in 1963, studied painting and fine arts in Nice, Boston, and Paris, and has been exhibiting her works since the early 1990s. From the very beginning of her career, Amer has been engaged in an investigation of the stereotypical notions, images, and techniques of femininity, as they are played out both in the visual arts and in everyday life. She lives and works in New York.

Embroidery, stitching, and sewing, traditionally identified as “female” techniques, have since become trademarks of Amer’s work, and have been used repeatedly by feminist artists since the 1960s as an ironic or subversive commentary on the male dominated techniques of painting and sculpture, especially as the heroic traditions of Abstract Expressionism and Monumental Sculpture.

Amer’s engagement with definitions and descriptions of femininity, as well as the continuous loosening of her embroideries towards more soft, tactile, and abstract surfaces, shifted increasingly toward other fields of reference. In “Counseils de Beauté” (Beauty Tips, 1993), Amer ironically embroidered several texts that give standard advice on the difficult task of keeping up personal hygiene. Other descriptions of beauty, femininity, and corporeality also find entrance into Amer’s work when she reproduces erotic stories and descriptions from both the Western canon of literature and Arabic cultural heritage. For example, the work “Private Rooms” (1997) features quotations from erotic narratives in the Ku’ran embroidered onto large canvas screens, and the work “Encyclopedy of Pleasures” (2001) features a series of cloth covered boxes embroidered with descriptions of all varieties of human eroticism found in Muslim medieval manuscripts.

She and fellow Muslim artist Ladan Naderi too this photo in protest of France's burqa fan.

Since the mid 1990s, Amer has also incorporated more direct images of sexuality into her richly textured canvases. Amer often uses images of women in explicit sexual poses, copied from softcore pornographic magazines, reproducing a selected image repetitiously across the canvas. Here she recalls another technique from the history of embroidery, namely patterning, the repetition of a selected image also results in the blurring of the image, as if to render it mute or abstract. At the same time, Amer has begun to color her canvases, pouring and blotching paint over parts of the painting before embroidering into it. By taking on methods of painting that were first introduced and canonized by Abstract Expressionism and combining them with the repetitious embroidery of pornographic images, Amer has arrived at a more openly pronounced criticism of (stereotypically) male artistic behavior. With Abstract Expressionism as the common point of reference for heroic artistic gestures and the sexist visualness of pornographic magazines as the definitive example of the male gaze, Amer has isolated two dominant strands in popular visual culture. By combining these with the subtle textuality of her intertwined threads, colored blotches and soft objects, Amer manages to continue her quiet critique of the stereotypes of domesticity, femininity, and sexuality, while simultaneously embracing the contested imagery. The slightly disconcerting feeling of unrest that often comes with her work thus can be seen as proof of the constant rejection of simple visual or thematic solutions to the questions Amer’s work has been asking for over a decade.

Born Diane Nemerov on March 14, 1923, in New York, New York. Diane Arbus was one of the most distinctive photographers in the twentieth century, known for her eerie portraits and offbeat subjects. Her artistic talents emerged at a young age; she was created interesting drawings and paintings while in high school. She married Allan Arbus in 1941 who taught her photography.

Working with her husband, Diane Arbus started out in advertising and fashion photography. They became quite a successful team with photographs appearing in such magazines as Vogue. In the late 1950s, she began to focus on her own photography. To further her art, Arbus studied with photographer Lisette Model around this time. She began to pursue taking photographs of people she found during her wanderings around New York City. She visited seedy hotels, public parks, a morgue, and other various locales. These unusual images had a raw quality and several of them found their way in the July 1960 issue of Esquire magazine. These photographs were a spring board for more work for Arbus.

By the mid-1960s, Diane Arbus was a well-established photographer, participating in shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York among other places. She was known for going to great lengths to get the shots she wanted. She became friends with many other famous photographers, such as Richard Avedon and Walker Evans.

While professionally Arbus continued to thrive in the late 1960s, she had some personal challenges. Her marriage ended in 1969, and she later struggled with depression. She committed suicide in her New York apartment on July 26, 1971. Her work remains a subject of intense interest, and her life was part of the basis of the 2006 film, Fur, starring Nicole Kidman as Arbus.

Self portrait

Artemisia Gentileschi was the most important woman painter of Early Modern Europe by virtue of the excellence of her work, the originality of her treatment of traditional subjects, and the number of her paintings that have survived (though only thirty-four of a much larger corpus remain, many of them only recently attributed to her rather than to her male contemporaries). She was both praised and disdained by contemporary critical opinion, recognized as having genius, yet seen as monstrous because she was a woman exercising a creative talent thought to be exclusively male. Since then, in the words of Mary D. Garrard, she "has suffered a scholarly neglect that is almost unthinkable for an artist of her caliber."

Like many other women artists of her era who were excluded from apprenticeship in the studios of successful artists, Gentileschi was the daughter of a painter. She was born in Rome on July 8, 1593, the daughter of Orazio and Prudentia Monotone Gentileschi. Her mother died when Artemisia was twelve. Her father trained her as an artist and introduced her to the working artists of Rome, including Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, whose chiaroscuro style (contrast of light and shadow) greatly influenced Artemisia Gentileschi's work. Other than artistic training, she had little or no schooling; she did not learn to read and write until she was adult. However, by the time she was seventeen, she had produced one of the works for which she is best known, her stunning interpretation of Susanna and the Elders (1610).

Among those with whom Orazio Gentileschi worked was the Florentine artist Agostino Tassi, whom Artemisia accused of raping her in 1612, when she was nineteen. Her father filed suit against Tassi for injury and damage, and, remarkably, the transcripts of the seven-month-long rape trial have survived. According to Artemisia, Tassi, with the help of family friends, attempted to be alone with her repeatedly, and raped her when he finally succeeded in cornering her in her bedroom. He tried to placate her afterwards by promising to marry her, and gained access to her bedroom (and her person) repeatedly on the strength of that promise, but always avoided following through with the actual marriage. The trial followed a pattern familiar even today: she was accused of not having been a virgin at the time of the rape and of having many lovers, and she was examined by midwives to determine whether she had been "deflowered" recently or a long time ago.

Perhaps more galling for an artist like Gentileschi, Tassi testified that her skills were so pitiful that he had to teach her the rules of perspective, and was doing so the day she claimed he raped her. Tassi denied ever having had sexual relations with Gentileschi and brought many witnesses to testify that she was "an insatiable whore." Their testimony was refuted by Orazio (who brought countersuit for perjury), and Artemisia's accusations against Tassi were corroborated by a former friend of his who recounted Tassi's boasting about his sexual exploits at Artemisia's expense. Tassi had been imprisoned earlier for incest with his sister-in-law and was charged with arranging the murder of his wife. He was ultimately convicted on the charge of raping Gentileschi; he served under a year in prison and was later invited again into the Gentileschi household by Orazio.

Artemisia's reputation was ruined by the publicity of the trial, one of the many reasons she is not often mentioned in art history then or today.

Self portrait

Mary Cassatt was born in 1844 in Pennsylvania, USA as the daughter of a wealthy merchant. At the age of seven her family left for Paris in France. After a few years of life in Paris, the family went back to the USA. Mary, impressed by all the art she had seen in Europe, surprised her parents by the wish to become an artist. Becoming an artist in the 19th century was as difficult for a woman as becoming a doctor. Society then had a different understanding of the role of women.

Finally Mary won and her parents allowed her to visit the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. In 1866 she went back to Paris. She copied the old masters in the Louvre and other museums. The young woman artist had acquired pretty good skills in traditional art style and in 1872 a Mary Cassatt painting was even accepted by the judges of the Salon.

Then she got to know Edgar Degas, an artist from the group of Impressionists who were refused by the Salon and had established their own show, the Salon des Refuses. Edgar Degas introduced her to his friends Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro and other Impressionist rebels.

Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas became good friends. Some art historians think she also was his mistress. This is however rather questionable as Degas was considered a convinced misogynist. Under the influence of Edgar Degas and the other Impressionists the artist Mary Cassatt changed her painting style. She used light colors and began to paint people.

Mary Cassatt's favorite subjects became children and women with children in ordinary scenes. Her paintings express a deep tenderness and her own love for children. But she never had children of her own.

The artist's artistic breakthrough came in 1892, when she received a commission for a mural for the Woman's Building at the Chicago World's Fair. The mural painting got lost after the fair and has not shown up until today.

Mary Cassatt was also an excellent printmaker. After experimenting with different printmaking techniques like etching and aquatint she finally discovered drypoint combined with aquatint as her favorite intaglio process. Between 1889 and 1890 she created a set of twelve wonderful drypoints. From 1890 to 1891 she made a series of ten color prints, known as The Ten. This series is considered as a landmark in Impressionist printmaking. She continued to make prints until 1896.

Mary Cassatt prints show a strong influence of Japanese prints and later of Renaissance paintings.

Mary Cassatt influenced Impressionism not only as an artist. She also had an important role in sponsoring and in financial promotion of Impressionist art. She often bought paintings of her friends when they were short of cash. And with her connections to rich American families, she encouraged many of her countrymen to buy Impressionist art. Quite a few of the great Impressionist art collections in the USA were established as a result of her activities. The collection of 19th century French paintings of the Havemeyers was largely mediated by her. The collection is now in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The artist Mary Cassatt would have made a poor career as a diplomat. She never held back with her opinion. Fortunately her wealth made her independent from what others thought about her. Especially when she grew older, her frankness could sometimes become insulting.

She did not like the modern artists like Henri Matisse or Pablo Picasso and spoke of "dreadful paintings". Even her Impressionist colleagues were whacked. For Claude Monet's late works - his famous water-lily paintings - she found the words "glorified wallpaper".

She had one thing in common with Edgar Degas and that was poor eyesight. When she died in 1926 at the age of 82 she was blind.

Self portrait

Born January 14, 1841, in Bourges, France, Berthe Morisot's father was a high-ranking government official and her grandfather was the influential Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard. She and her sister Edma began painting as young girls. Despite the fact that as women they were not allowed to join official arts institutions, the sisters earned respect in art circles for their talent.

Berthe and Edma Morisot traveled to Paris to study and copy works by the Old Masters at the Louvre Museum in the late 1850s under Joseph Guichard. They also studied with landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot to learn how to paint outdoor scenes. Berthe Morisot worked with Corot for several years and first exhibited her work in the prestigious state-run art show, the Salon, in 1864. She would earn a regular spot at show for the next decade.

In 1868, fellow artist Henri Fantin-Latour introduced Berthe Morisot to Edouard Manet. The two formed a lasting friendship and greatly influenced one another's work. Berthe soon eschewed the paintings of her past with Corot, migrating instead toward Manet's more unconventional and modern approach. She also befriended the Impressionists Edgar Degas and Frédéric Bazille and in 1874, refused to show her work at the Salon. She instead agreed to be in the first independent show of Impressionist paintings, which included works by Degas, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Claude Monet, and Alfred Sisley. (Manet declined to be included in the show, determined to find success at the official Salon.) Among the paintings Morisot showed at the exhibition were The Cradle, The Harbor at Cherbourg, Hide and Seek, and Reading.

In 1874, Berthe Morisot married Manet's younger brother, Eugne, also a painter. The marriage provided her with social and financial stability while she continued to pursue her painting career. Able to dedicate herself wholly to her craft, Morisot participated in the Impressionist exhibitions every year except 1877, when she was pregnant with her daughter.

Berthe Morisot portrayed a wide range of subjects-from landscapes and still lifes to domestic scenes and portraits. She also experimented with numerous media, including oils, watercolors, pastels, and drawings. Most notable among her works during this period is Woman at Her Toilette (c. 1879). Later works were more studied and less spontaneous, such as The Cherry Tree (1891-92) and Girl with a Greyhound (1893).

After her husband died in 1892, Berthe Morisot continued to paint, although she was never commercially successful during her lifetime. She did, however, outsell several of her fellow Impressionists, including Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. She had her first solo exhibition in 1892 and two years later the French government purchased her oil painting Young Woman in a Ball Gown. Berthe Morisot contracted pneumonia and died on March 2, 1895, at age 54.

Sources: Ghada Amer, Diane Arbus, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot

Upcoming: Kathe Kolwitz, Tracey Emin, Sherry Levine, Ana Mendieta, Yayoi Kusama, Jenny Holzer, Kara Walker, Barbra Kurger, Remedios Varo, Frida Kahlo, Julie Mehretu, Yoko Ono, Lee Krasner, Marina Abramović and Alice Neel.