Goodbye Capitalism, Hello Neo-Feudalism.

Infallible Corporate Media Proclaims Bad Economy is Caused by Bad Lazy People and Stuff, Cut it Out! Just Work Hard and the Capitalist Fairy will Reward You!

Disabled, or just desperate?

Rural Americans turn to disability as jobs dry up

The lobby at the pain-management clinic had become crowded with patients, so relatives had gone outside to their trucks to wait, and here, too, sat Desmond Spencer, smoking a 9 a.m. cigarette and watching the door. He tried stretching out his right leg, knowing these waits can take hours, and winced. He couldn’t sit easily for long, not anymore, and so he took a sip of soda and again thought about what he should do.

He hadn’t had a full-time job in a year. He was skipping meals to save money. He wore jeans torn open in the front and back. His body didn’t work like it once had. He limped in the days, and in the nights, his hands would swell and go numb, a reminder of years spent hammering nails. His right shoulder felt like it was starting to go, too.

But did all of this pain mean he was disabled? Or was he just desperate?

He wouldn’t even turn 40 for a few more months.

An hour passed, and his cellphone rang. He picked it up, said hello and hung up - another debt collector. He rubbed his right knee. Maybe it would get better. Maybe he would still find a job.

His mother had written a number the night before and told him to call it, and he had told her he’d think about it. She wanted him to apply for disability, like she had, like his girlfriend had, and like his stepfather, whom he now saw shuffling out of the pain clinic, hunched over his walker, reaching for a hand-rolled cigarette. Spencer got out of the truck. He lit his own.

“Remember we were talking about it last night?” he asked Gene Ruby. “Remember we were talking about signing up?”

“Yeah,” said Ruby, 64.

“Remember Mama said there was a number you got to call?”

“She’s got the number,” Ruby said. “The Social Security number.”

Spencer kept asking questions. What would Social Security want to know? How often are people denied? But he didn’t mention the one that had been bothering him the most lately: Was he a failure?

“There’s a stigma about it,” Spencer said, thinking aloud. “Disabled. Disability. Drawing a check. But if you’re putting food on the table, does it matter?”

Then: “I could probably still work.”

He put his stepfather’s walker in the truck bed, got behind the wheel, started another cigarette and, pulling out of the pain clinic’s parking lot, headed for home.

The decision that burdened Desmond Spencer was one that millions of Americans have faced over the past two decades as the number of people on disability has surged. Between 1996 and 2015, the number of working-age adults receiving disability climbed from 7.7 million to 13 million. The federal government this year will spend an estimated $192 billion on disability payments, more than the combined total for food stamps, welfare, housing subsidies and unemployment assistance.

The rise in disability has emerged as yet another indicator of a widening political, cultural and economic chasm between urban and rural America.

A nation of rising disability: What’s the rate in your area?

Across large swaths of the country, disability has become a force that has reshaped scores of mostly white, almost exclusively rural communities, where as many as one-third of working-age adults live on monthly disability checks, according to a Washington Post analysis of Social Security Administration statistics.

Rural America experienced the most rapid increase in disability rates over the past decade, the analysis found, amid broad growth in disability that was partly driven by demographic changes that are now slowing as disabled baby-boomers age into retirement.

The increases have been worse in working-class areas, worse still in communities where residents are older, and worst of all in places with shrinking populations and few immigrants.

All but three of the 136 counties with the highest rates - where more than one in six working-age adults receive disability - were rural, the analysis found, although the vast majority of people on disability live in cities and suburbs.

The counties - spread out from northern Michigan, through the boot heel of Missouri and Appalachia, and into the Deep South - are largely racially homogeneous. Eighteen of the counties were majority black, but the remaining counties were, on average, 87 percent white. In the 2016 presidential election, the majority-white counties voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump, whose rhetoric of a rotting nation with vast joblessness often reflects lived experiences in these communities.

Most people aren’t employed when they apply for disability - one reason applicant rates skyrocketed during the recession. Full-time employment would, in fact, disqualify most applicants. And once on it, few ever get off, their ranks uncounted in the national unemployment rate, which doesn’t include people on disability.

The decision to apply, in many cases, is a decision to effectively abandon working altogether. For the severely disabled, this choice is, in essence, made for them. But for others, it’s murkier. Aches accumulate. Years pile up. Job prospects diminish.

“What drives people to [apply for] disability is, in many cases, the repeated loss of work and inability to find new employment,” said David Autor, an economist with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied rising disability rates. “Many people who are applying would say, ‘Look, I would like to work, but no one would employ me.’ ”

In that position now, Spencer, a slight man with luminous blue eyes, drove deeper into western Alabama. He steered through Walker County, where nearly one in five working-age adults are on disability, and into Lamar County, where the disability rate has more than doubled over the past 20 years, arriving in the town of Beaverton, population 273, where even the 55-year-old mayor is drawing a disability check.

He pulled up to a small house alongside a quiet country road, got out and looked around. There was only forest and hills and sun. “Man, I love it out here,” he said.

“Ain’t going nowhere,” Ruby agreed.

Spencer, who wears mud-caked boots and camouflage and brags of burning trash “like a proper redneck,” has grown so enamored of rural life that he’s sometimes surprised when he remembers that he spent most of his life elsewhere. He grew up just outside of Peoria, Ill., dropped out of school at 14, secured his GED, served two stints in prison for felony burglary before he turned 20 and started working roofing jobs, following other family members into manual labor, like his grandfather who built bridges, and his mother, who worked at a stove factory.

His work as a roofer had been a constant thread through his life, from one state to the next, one job to another. And so it had been again in 2005 when he followed family members to Lamar County, which is 86 percent white and 11 percent black, and was then navigating a long decline in population and manufacturing jobs - one plant moved to Mexico, another to the Dominican Republic. He nonetheless found a roofing job quickly, settling into a life that, for a time, felt as safe as it was comfortable. But then came the recession, and the uneven recovery, and jobs started drying up, and four years ago, as the county poverty rate climbed to 24 percent, the roofing company let him go.

He figured he’d find more work right away. But weeks became months, and he started doing what he calls “odds and ends” - work as a welder, a ranch hand, even a full-time garbage collector - but nothing restored the stability that had gone missing.

He opened the front door to his house. He walked past a small sign in a living room cabinet that said, “BELIEVE in the beauty of your dreams,” and into a bathroom that he had recently remodeled and where another sign said, “DON’T QUIT: Stick to the fight when you’re hardest hit; it’s when things seem worst that you must not quit.”

He had been reading a book lately about the power of positivity. He would sometimes think about it when putting in job applications, or when he was behind his house, looking at his possessions. There was the old Kia that hadn’t run in two years. The pile of aluminum cans for which he’d make 40 cents on the pound. The dozens of used tires a repair shop had paid him to haul away. He never knew what would turn out to be worth something.

He was blessed, he always tried to remind himself.

But increasingly there were days when Spencer knew he was faking a belief, once so strong, that everything would work out. There were days like today, when he sat in a pew in a small church in Lamar County, listening to members of the congregation ask for prayers for health issues:

“My mother-in-law is in the hospital this week, and she has some heart problems,” a man said.

“My body is not cooperating with my job whatsoever,” a woman said.

“I got my back surgery,” another man said. “I hope it takes this time.”

An hour later, Spencer was home again. His knee was hurting once more, as it had on and off ever since he fell from a roof during a construction job two years ago. He’d never had it checked out because he’d never had insurance, and he didn’t mention it now because everyone at the house seemed worse off than he was. His mother, Karen Ruby, 60, who has cirrhosis of the liver, was sitting at the kitchen table with her head in her hands, saying, “I don’t know when I’m going to be able to get back into church.” His stepfather was stooped beside her, next to a wheelchair, smoking a cigarette. His girlfriend, Tasha Harris, 34, a thin, ashen woman whose back was often thrown out, was upstairs in the dark after leaving church early because she hadn’t felt well.

“I need angel food cake,” his mother told him before he headed out to the store. “Write it down.”

“Angel food cake? All right, I’ll be back,” he said, walking toward the door.

“I feel like crap,” said Harris, who had come downstairs to see him off.

“I’m sorry,” Spencer quietly told her, then went outside to his truck and pulled onto the road.

This is how Spencer spends most of his days, ferrying to the dollar store and back, collecting soda, cigarettes and whatever else his family may want, and consoling them when he’s around. Most days he doesn’t mind. He likes feeling like the strong one when it seems as though almost everyone he knows is either applying for or already on disability. Just the night before, during a family dinner, it had struck him again.

“She walks, and it breaks her bones,” his cousin, who applied for disability after a nervous breakdown, had said of another relative receiving disability.

“She falls a lot,” added his aunt, who collects $733 monthly in disability checks because of back pain.

Spencer, listening to the conversation, had looked around. At the table was another cousin, who has bipolar disorder and receives $701 per month. Beside her was her boyfriend, whose mom had applied for disability, too. Spencer glanced at the ceiling and sighed.

“The whole world is on disability,” he said.

“It’s a tough world,” someone else said.

And now that world was spread out before him as he drove through downtown Beaverton, past a value store, a post office that closes at noon, a bank that shuttered during the recession, a gas station that hasn’t been open for as long as Spencer has been here.

He saw a large roadside banner that said, “APPLY NOW IMMEDIATE OPENINGS,” and cursed to himself. He didn’t know how many times he’d gone in that upholstery factory and asked about a job, any job, and was turned away. He saw another factory, this one an equipment supplier, where he thought he’d need an act of Congress to get hired. Up ahead was a horse-trailer shop. Three consecutive months he had gone through the door, and each time they’d said, “Next month, try us.” Meanwhile, he tried to sign up for a welding class at a community college, but failed the enrollment math exam.

He pulled up to the Piggly-Wiggly. He collected cake mix and three 12-packs of Mountain Dew for Harris, who he knows can go through 24 cans in a day, and was driving home, passing everywhere he couldn’t get a job, when he thought of another opportunity. There was still that place that might need help with welding, a skill he’d picked up after he lost his roofing job. He had told himself he’d go first thing on Monday morning. Arrive by 8:30 a.m. Show the enthusiasm and dedication of someone worth hiring.

Walking back into his house, he placed the cake mix on the counter and heard his mother, who was in her room, with the curtains drawn and the television on, holding an unlit cigarette.

“Desmond?” she said, her voice raspy from a case of strep throat. “Is that black lighter in there?”

“Black lighter?” he said.

“I got a sore throat,” she said.

“I don’t see it,” he said of the lighter.

“Me and Gene, neither of us got a lighter now,” she said.

He began placing empty soda cans into a plastic bin and clearing the kitchen table of the dishes from the night before, then heard Harris at the bottom of the steps.

“Baby?” she said. “My head is still killing me.”

“I got you something for your headache,” he said, handing her some medicine and a 12-pack of Mountain Dew, and went back to the kitchen.

“Desmond,” Harris softly called after him.

“Yeah?” he said, returning.

“Do you have a cigarette?”

He gave her one, finished with the kitchen, then limped to the living room. He lowered himself onto the couch, his knee hurting worse than earlier, and flipped on the television.

Something had to change.

Everyone in his life has been telling him what that something is.

You’re hurting more and more, his mother said. And not getting any younger.

There aren’t jobs for you here, a friend said. Think that’ll change anytime soon?

We all need help now and again, his girlfriend said. Don’t be ashamed of being on disability.

You’re a grown man, his stepfather said. Bring in some money.

That was what Spencer was thinking about - money, and not having any - when one day Harris found him sitting alone on the back porch in the quiet, going through another cigarette. “Checks are in,” she said of his parents’ monthly disability payments, which are cumulatively worth $3,616 and support everyone in a house that, at that moment, was low on just about everything.

“We’re going to the store,” Harris said.

“How you getting there?” he asked.

“The truck.”

“It ain’t got no gas, though.”

“I got to take your mom to the bank.”

“Maybe she’ll loan you 10 for gas.”

Harris disappeared back into the house, and Spencer went back to his cigarettes and thoughts. It didn’t seem right to him, living off his parents’ disability checks and borrowing money from them. But he felt trapped. He couldn’t leave Lamar County with his mother so sick. And the only money he had coming in was the monthly $425 an elderly friend paid him to tend his horses and keep him company on lonely afternoons, and it was never enough to cover everything. This month it was socks. Harris needed socks. And what kind of man can’t afford socks? His grandfather used to tell him that a man isn’t a man unless he owns land, and now here he was, years later, not feeling like one at all.

He found Harris in the kitchen. “Ask him for $40,” she told him. “And I’ll get 10 more from him to buy socks.”

Gene Ruby was at the computer when Spencer approached him. The question came quickly and quietly. “Could I borrow 40? And give it back to you right here soon?” he asked. “I promise.”

A few hours after pocketing the money, Spencer climbed back into the truck Gene made the payments on and started it with the gas Karen had paid for. Harris got in beside him. They had been together for seven years and rarely disagreed, except for that day two years before when Harris said she was thinking of applying for disability on account of back pain. He told her not to do it. People would look down on them. They would find jobs. Don’t lose hope.

A light blinked on the dashboard.

“Transmission’s hot,” Harris said. “I told you it did that to me the other day.”

He pressed down on the accelerator.

“No, don’t do that,” she said. “Just put it in neutral and coast. Try not to mash the gas at all.”

“We’re running it into the ground, is what we’re doing,” he said, lighting another cigarette.

Harris looked at him. She could tell he was getting frustrated. Just about everything these days made him that way. He had begun complaining more, not just about the truck or the pain in his knees and hands, but about all of Lamar County. He told her there would never be jobs here for them. Maybe she had been right about applying for disability. His injuries weren’t getting better, and he wasn’t getting hired, and how much longer could he ask for help with groceries? Help with gas? Help with transportation? Help with everything?

He moved the truck out of neutral and back into drive. The store was 20 miles up the road in Hamilton, the largest town in the area, with a population of 6,814. Harris’s brother and his wife lived on its outskirts, and in the falling light, they went to visit, pulling up to a tidy mobile home set beside a large field. Harris’s sister-in-law, Chastity, who was working full time at a calling center, came outside. Then followed Harris’s brother, Josh, 28, broad-shouldered and shirtless. They handed a plate of barbecue pork to Spencer and Harris, both of whom had skipped lunch that day. The plate went back and forth between them.

“I just went and got a job at Wrangler,” Josh said of a distribution center in nearby Hackleburg.

Spencer stopped eating. He looked up.

“Is that right, man?” Spencer asked, and Josh nodded. “That’s great. I’m proud of you. Man, I’m happy about that. I’m happy you got that.”

“Me, too,” Josh said. “It pays good.”

“Monday, I’m going to go back to that shop where . . . I heard they need help,” Spencer said. “Hopefully, I can weasel my way in there.”

“You can,” Josh said. “Put it in your mind, and you can do it.”

“I had an inspiration book,” Spencer said. “You wake up and put it in your head: ‘God’s got my back. I got this job.’ ”

There was a moment of quiet.

“I’m glad you got that, man,” Spencer said again. “I’m proud of you.”

“Sometimes, it’s just the right place at the right time.”

Spencer and Harris finished the barbecue, hugged their relatives goodbye and got back into the truck. He drove to a strip mall that had a Shoppers Value Foods, a Check Into Cash and a title loan shop. He glanced at a sign outside a Sonic fast-food restaurant: “Now Hiring All Shifts.” He sometimes considered applying for a fast-food job. But how, after making $20 an hour at some jobs, could he take one paying $7.25?

He parked and went inside the grocery store.

Spencer was looking at a piece of paper on the coffee table. It was the number to the Social Security office his mother had given him. He and Harris sat on the couch in the living room, and she handed him a telephone.

“You got to call,” she said.

“I’m nervous,” he said.

“Don’t be nervous,” she said. “They’re not going to reach through the phone and get you.”

He didn’t say anything for a moment, just held the phone.

“What do I do and say?” he asked.

“Call that number and do whatever they tell you to do.”

He took in a breath and exhaled slowly.

“I guess I’ll call,” he said, punching in the number, and then came a voice on the other end, with that question again, the one he rarely had the courage to ask himself:

“Are you disabled?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“How long have you been disabled?”

“Two years.”

“How are you supporting yourself?”

“Living off my mom.”

“Is this a permanent disability?”

“Uhh,” he began. “I don’t think . . . ”

He looked at the floor and leaned forward.

“Yeah,” he said quietly. “Yeah, I don’t think it’s getting no better.”

He scheduled an appointment for an interview at the local Social Security office the following month. He hung up, stood and, appearing dazed, told Harris, “I didn’t like it at all.” She gave him a sympathetic look and left him alone on the couch.

He was there again four days later on a Monday morning.

The entire house was dark. Spencer was in his pajamas, watching television. Harris was soon beside him, also in pajamas. “I think I’m getting sick,” she said, and he didn’t answer. She went to another room and came back with Ruby’s laptop, which she uses every Monday morning to look at job listings.

“I ain’t checked it in a week,” she said.

“Oh my God,” he sighed, flipping through channels.

“Do you know anything about pop-ups?” she asked, looking at the computer. “Man, I’ve had, like, a hundred pop-ups.”

“Look, the new ‘Walking Dead,’ ” Spencer said, coming to another channel.

She pulled up her email and clicked on one that listed service positions within 25 miles. “Okay,” she said. “Here we go.” She saw three postings: “Customer Service/Telecommute,” “Telecommute Consultant” and “Product Tester.” She didn’t investigate any of them, instead going back to her inbox. She found another email with more listings.

“Erber?” she asked. “We don’t even have an Erber place around here.”

“Uber,” Spencer said.

“Uber, Erber, whatever,” she said, closing the computer.

An hour passed, then another, and Spencer stayed on the couch. He would not apply for the welding job today. He wanted to focus on securing disability.

“I got to go get dressed,” he said, looking down at his clothing. “What a loser.”

He returned in torn jeans and, with nothing better to do, went outside. He limped to the truck and fiddled with jumper cables. He set a fire inside an iron bin and burned some trash. He inspected a sheet of aluminum he had found, wondering how much he could sell it for. He walked into the woods and walked out. He looked at the road. A car hadn’t passed in a long while. It was 1 in the afternoon. The day already felt over.

Disabled, or just desperate?

U.S. College Grads See Slim-to-Nothing Wage Gains Since Recession

Petroleum engineers and philosophy majors are bucking the trend

The bachelor's degree - long a ticket to middle-class comfort - is losing its luster in the U.S. job market.

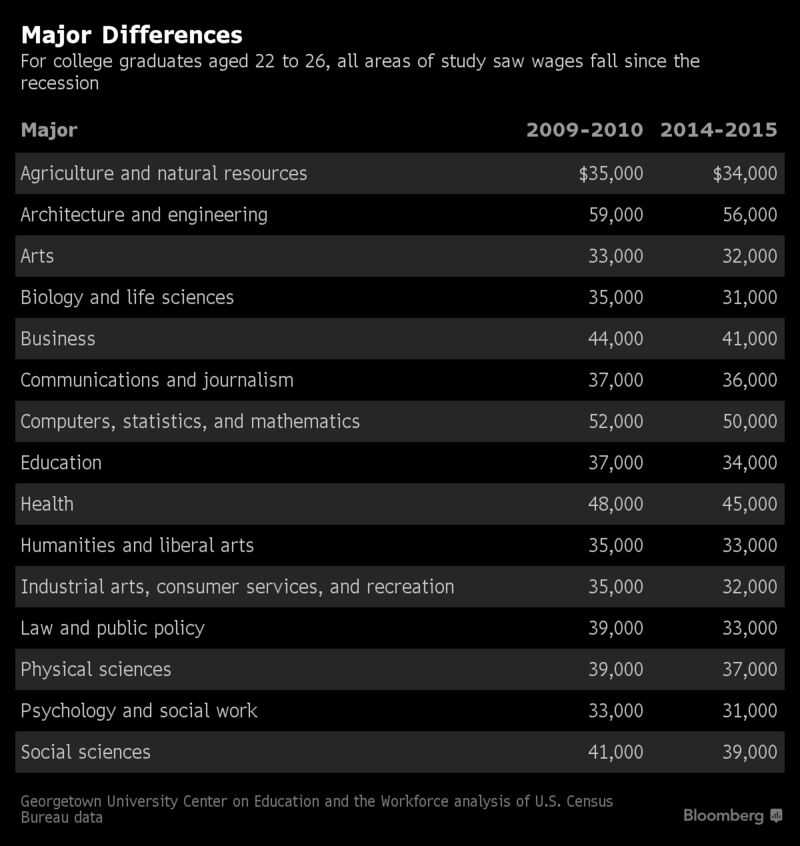

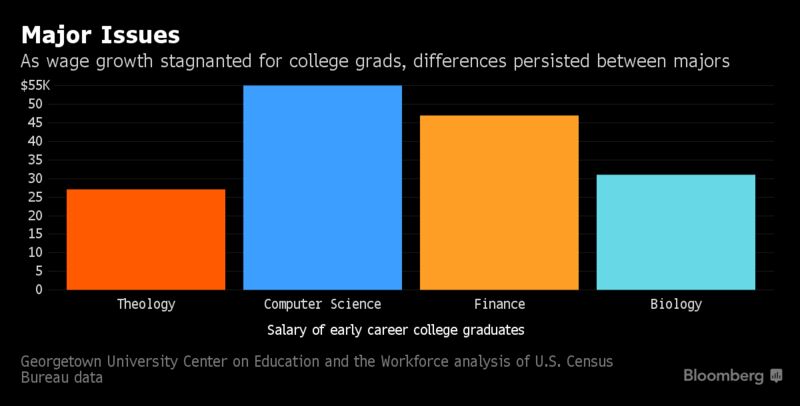

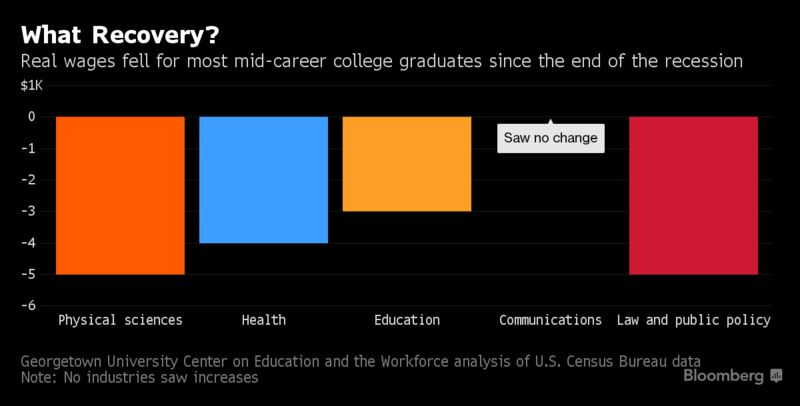

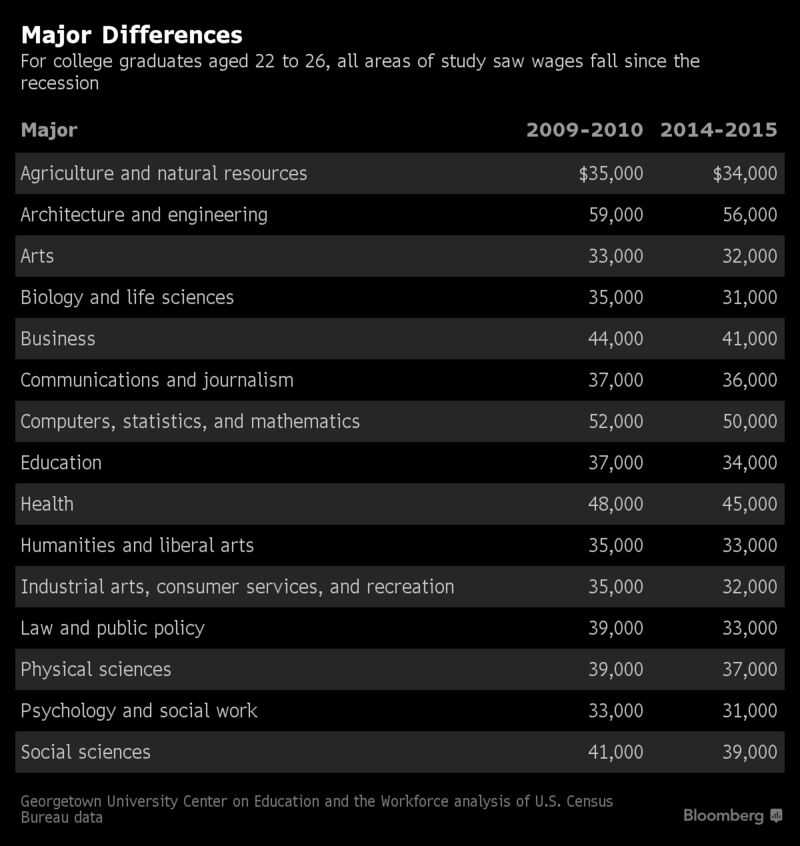

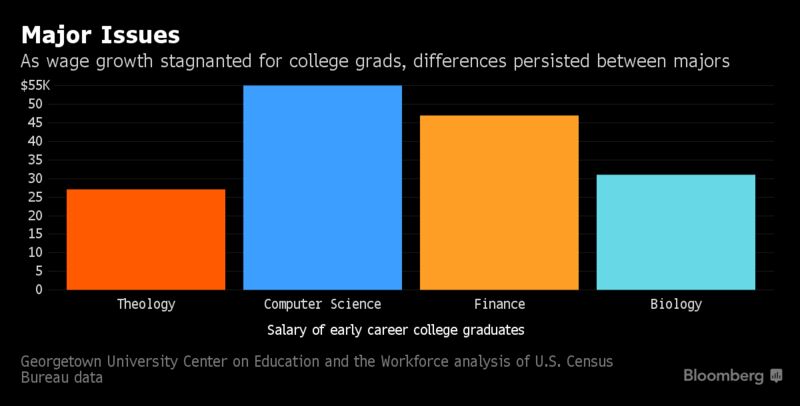

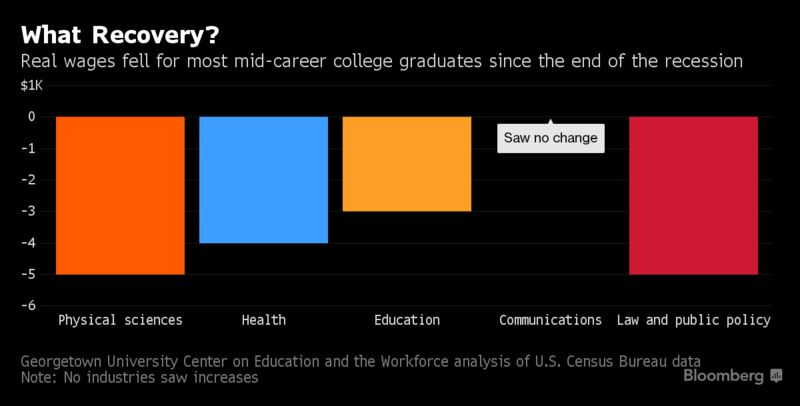

Wages for college graduates across many majors have fallen since the 2007-09 recession, according to an unpublished analysis by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce in Washington using Census bureau figures. Young job-seekers appear to be the biggest losers.

What you study matters for your salary, the data show. Chemical and computer engineering majors have held down some of the best earnings of at least $60,000 a year for entry level positions since the recession, while business and science graduates's paychecks have fallen. A biology major at the start of their career earned $31,000 on an annual average in 2015, down $4,000 from five years earlier.

"It has been like this for the past five, six years now," said Ban Cheah, a research professor at Georgetown who compiled the data. "It's a little depressing."

The outlook for experienced graduates, aged 35 to 54, is brighter, with wages generally stable since the crisis.

The economic premium of a bachelor's flattened after the recession, according to a 2016 National Bureau of Economic Research paper by Robert Valletta, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Among the factors at play are advances in technology and automation, which are not only taking away U.S. manufacturing jobs, but also having an impact on white collar workers, Valletta found. Legal clerks and researchers are increasingly finding their jobs supplanted by computers, for example.

Some majors are bucking the wage-stagnation trend. An experienced petroleum engineering major earned $179,000 a year on average in 2015, up $46,000 from five years prior, according to the Georgetown analysis. Beyond those with special technical skills, philosophy and public policy majors have also seen their earnings rise.

So how can you boost your career earnings potential? A graduate's level degree is increasingly offering the bigger salary bump, according to Cheah. The wage gap between graduate degree-holders and undergrads has been growing, he said.

It's also important to remember that a student's major is just one determinant of their future earnings potential. The training experience from internships, debt levels and soft skills also help shape salary and job prospects, said Jeff Selingo, who writes about higher education and is a professor of practice at Arizona State University.

"Just getting a degree doesn't matter anymore," said Selingo. "What matters more are the undergraduate experiences that you have."

U.S. College Grads See Slim-to-Nothing Wage Gains Since Recession

Underemployment of young people is the highest it has been in 40 years

Almost one in five young people have fewer hours of work than they want, with underemployment in the youth labour force at its highest level in 40 years.

When unemployment is taken into account, the proportion of people aged 15 to 24 who are either without work or enough hours of work is now at 31.5 per cent.

The so-called "under-utilisation rate" which combines unemployment and underemployment levels is higher than it was during the 1990s recession.

Josh Sandman, 19, is one of 659,000 young Australians who are either unemployed or underemployed - having some work, but wanting more hours.

He does 10 hours a week of volunteer work as a freelance graphic designer in the hope it will lead to a full-time job. He had about 20 hours a week of paid work at a takeaway food outlet in Adelaide until a couple of weeks ago.

"If I had lost my job and was not living at home I would be on a couch or homeless right now," he said.

The new Brotherhood of St Laurence analysis shows 18 per cent of young people are underemployed, the highest level it has ever been since 1978 when the Australian Bureau of Statistics first started collecting the data.

Underemployment is now much higher than youth unemployment which is at 13.5 per cent.

Unemployment was less than 10 per cent and underemployment was at 11 per cent just before the global financial crisis.

The new analysis uses data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey and the Department of Employment.

To be released on Monday, the Brotherhood of St Laurence publication, Generation Stalled: young underemployed and living precariously in Australia has found that the rise of underemployment can not be explained by the growing number of young people combining study with work.

"[T]he rise in the percentage of casual and part-time jobs has mostly been among young workers who are not studying," the report says.

Young people are now far more likely to be in casual and part-time jobs now than they were in the year 2000. The gap between the actual hours worked and the hours young people want to work has widened.

"The employment outlook for many young Australians today is profoundly different than it was when their parents and grandparents first started work," said Tony Nicholson, executive director of the Brotherhood of St Laurence.

"The record growth of underemployment particularly hurts the 60 per cent of young people who don't go to university - they face a much more uncertain future than previous generations."

Mr Nicholson said in the past, young people could leave school early and get a job in a factory, mail room, bank or a state-owned enterprise get training and improve their prospects.

"They had every chance to build a good life for themselves and their families. These opportunities have shrunk as the economy has changed and insecure jobs are leading to far more uncertain prospects for the new generation," he said.

"We need to redouble our efforts to build the capabilities of disadvantaged young people in this very challenging scenario. Tinkering with welfare payments is not the answer here."

The prevalence of young workers who are not students on permanent contracts has fallen from 61.8 per cent in 2008 to 53.2 per cent in 2014.

The proportion of students in casual work has fallen in recent years.

Underemployment of young people is the highest it has been in 40 years

Eight lessons from Barcelona en Comú

On 24 May 2015, the citizen platform Barcelona en Comú was elected as the minority government of the city of Barcelona. Along with a number of other cities across Spain, this election was the result of a wave of progressive municipal politics across the country, offering an alternative to neoliberalism and corruption.

After 20 months in charge of Barcelona, here are eight things we have learned from Ada Colau and Barcelona en Comú.

With Ada Colau - a housing rights activist - catapulted into the position of Mayor, and with a wave of citizens with no previous experience of formal politics finding themselves in charge of their city, BComú is an experiment in progressive change that we can’t afford to ignore.

After 20 months in charge of the city, we try to draw some of the main lessons that can help inspire and inform a radical new municipal politics that moves us beyond borders and nations, and towards a post-capitalist world based on dignity, respect and justice.

1. The best way to oppose nationalist anti-immigrant sentiment is to confront the real reasons that life is shit

There is no question that life is getting harder, more precarious, more stressful, and less certain for the majority of people. In the US and across Europe, reactionaries, racist and nationalist politicians are blaming this on two things - immigrants, and ‘outside forces’ that challenge national sovereignty. Whilst Trump and Brexit are the most obvious cases, we can see the same phenomenon across Europe, ranging from the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany through to Front National in France.

In Barcelona, there is a relative absence of public discourse that blames the social crisis on immigrants, and most attempts to do so have fallen flat. On the contrary, on 18 February over 160,000 people flooded the streets of Barcelona to demand that Spain takes in more refugees. Whilst this demonstration was also caught up with complexities of Catalan nationalism and controversy over police repression of migrant street vendors, it highlighted the support for a politics that cares for migrants and refugees.

The main reason for this is simple - there is a widespread and successful politics that provides real explanations of why people are suffering, and that fights for real solutions. The reason you can’t afford your rent is because of predatory tourism, unscrupulous landlords, a lack of social housing, and property being purchased as overseas investments. The reason social services are being cut are because the central government transferred huge amounts of public funds into the private banks, propping up a financial elite, and because of a political system riddled with corruption.

Whilst Barcelona played a leading role in initiating a network of “cities of refuge”, simply condemning anti-immigrant nationalism is not enough. In a climate where popular municipal movements are providing a strong narrative as to what they see as the problem - and identifying what they’re going to do about it - it’s incredibly difficult for racist and nationalist narratives based on lies and hatred to take root.

2. Politics does not have to be the preserve of rich old white men

Ada Colau is the first female mayor of Barcelona. She is a co-founder of BComú, and was formerly the spokesperson of the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (Mortgage Victims Platform), a grassroots campaign challenging evictions and Spain’s unjust property laws. Colau leads a group of eleven district councillors, seven of whom are women, whose average age is 40.

BComú’s vision of a “feminized politics” represents a significant break with the existing political order. “You can be in politics without being a strong, arrogant male, who’s ultra-confident, who knows the answer to everything”, Colau explains. Instead, she offers a political style that openly expresses doubts and contradictions. This is backed by a values-based politics that emphasizes the role of community and the common good - as well as policies designed to build on that vision.

The City Council’s new Department of Life Cycles, Feminisms and LGBTI is the institutional expression of these values. It has significantly increased the budget for campaigns against sexist violence, as well as leading a council working group that looks to identify and tackle the feminization of poverty.

The changing face of the city council is reinforced by BComú’s strict ethics policy, Governing by Obeying, which includes a €2,200 (£1850) monthly limit on payments to its elected officials. Colau takes home less than a quarter of the amount claimed by her predecessor Xavier Trias. By February 2017, €216,000 in unclaimed salaries had been paid into a new fund that will support social projects in the city.

3. A politics that works begins by listening

BComú started life with an extensive process of listening, responding to ordinary peoples’ concerns, and crowd-sourcing ideas - as summarized in its guide to building a citizen municipal platform.

Drawing on proposals gathered at meetings in public squares across the city, BComú created a programme reflecting immediate issues in local neighbourhoods, city-wide problems and broader discontent with the political system. Local meetings were complemented by technical and policy committees, and an extensive process of online consultation.

This process resulted in a political platform that stressed the need to tackle the “social emergency” - problems such as home evictions on a huge scale, or the effect of uncontrolled mass tourism. These priorities came from listening to citizens across the city rather than an echo-chamber of business and political elites. BComú’s election results reflected this broader appeal: it won its highest share of the vote in Barcelona’s poorest neighbourhoods, in part through increasing turnout in those areas.

On entering government, BComú then began to implement an Emergency Plan that included measures to halt evictions, hand out fines to banks leaving multiple properties empty, and subsidise energy and transport costs for the unemployed and those earning under the minimum wage.

4. A politics that works never stops listening

Politics doesn’t happen every four years - it is the everyday process of shaping the conditions in which we live our lives. This means that one of the central tasks of a politics that works is to forge a new relationship between citizens and the institutions that we use to govern our societies.

For BComú, the everyday basis of politics means citizens and civil society organisations directly shaping the strategic plan of their city. It means not just consultation, but active empowerment in helping move citizens from being ‘recipients’ of a politics that is done to them, to active political agents that shape the every-day life of their city.

In the first months of occupying the institutions, BComú introduced an open-source platform, Decidim Barcelona, for citizens to co-create the municipal action plan for the city. Over 10,000 proposals were registered by the site’s 25,000 registered users. While that’s a small share of the city’s population, the online process was complemented by over 400 in-person meetings.

The Decidim platform is now being adapted to run participatory budgetary pilot-schemes in two districts, as well as being used in the ongoing development of new infrastructure, pedestrianisation and transport schemes. Meanwhile, the municipal Department of Participation is undertaking a systematic rethinking of the ‘meaning’ of participation, looking to move away from meaningless ‘consultations’ and towards methods for active empowerment.

This is an imperfect process - and BComú have got things wrong at times, such as the failure to properly engage when introducing a SuperBlock in the Poblenou district - but the principle is simple. To govern well, you must create new processes for obeying citizens’ demands.

At the same time, the structures that built BComú remain in place, with 15 neighbourhood groups and 15 thematic working groups providing an ongoing link between activists and institutions. No structure is perfect, and it remains unclear if these working groups can help BComú avoid “institutionalization” and remain connected to social movements, but the hope is that this model provides a basis for remaining in touch with grassroots concerns.

5. Politics does not begin with the Party

BComú is not a ‘local’ arm of a bigger political party, and does not exist merely as a branch of a broader strategy to control the central political institutions of the nation-state. Rather, BComú is one in a series of independent citizen platforms that have looked to occupy municipal institutions in an effort to bring about progressive social change.

From A Coruña to Valencia, Madrid and Zaragoza, these municipal movements are the direct effort of citizens rejecting the old mode of doing politics, and starting to effect change where they live. Instead of a national party structure, they coordinate through a “network of rebel cities” across Spain. Most immediately, this means coordinating press releases and actively learning from how one another engage with urban problems.

That doesn’t mean that BComú can reject political parties entirely. While the initiative arose from social movements, it ended up incorporating several existing political parties in its platform. These include Podemos - another child of the 15-M movement - and the Catalan Greens-United Left party (ICV-EUIA), which had consistently been a junior coalition partner in city councils headed by the centre-left Partit dels Socialistes de Catalunya (PSC) from 1979 until 2011.

These parties continue alongside BComú, with their own completely separate organizational and funding structures. But entering BComú has forced existing parties to significantly change how they operate. Coalition negotiations encouraged the selection of new councillors (only two of the elected candidates have previously held office), and they are subject to a tough Ethics Code that considerably increases their accountability.

The fluid relationship between the new coalitions and political parties allows for multiple levels of coordination, without having to pass through a rigid central leadership. It may also be replicated in regional government, where the recently formed Un Pais En Comú seeks to replicate the city government coalition across Catalunya. On a terrain that contains a different set of politics - not least a strong national-separatist sentiment - it remains to be seen whether this latest initiative will be successful.

6. Power is the capacity to act

BComú does not subscribe to traditional notions of power, whereby if you hold public office, you somehow ‘have’ power. On the contrary, power is the capacity to bring about change, and the ‘occupation of the institutions’ is only one part of what makes change possible.

BComú emerged after almost a decade of major street-protests, anti-eviction campaigns, squatting movements, anti-corruption campaigns, and youth movements - the most visible form being the ’15-M’ or ‘indignados’ protests that began in 2011. After years of being at a high-level of mobilization, many within these movements made a strategic wager - we’ve learned how to occupy the squares, but what happens if we try to occupy the institutions?

Frustrated by the limits of what could be achieved by being mobilized only outside of institutions, the decision to form BComú was to try to occupy the institutions as part of the same movement that occupied the squares. In practice, this is not so simple.

Politics is a messy game, full of compromises forced by working in a world of contradictions. In the most practical sense, BComú may be leading the council, but it holds only 11 of the 41 available seats. Six other political parties are also represented on the council, mostly seeking to block, slow-down or weaken its initiatives. Frustrated by these moves - and overwhelmed by the demands of the institutions - BComú formed a governing coalition with the PSC, a move supported by around 2/3 of its registered supporters. But it remains a minority government, and two left parties that refused a similar pact responded by stepping up their block on almost all legislative initiatives. The resulting political crisis delayed the passing of the city’s 2017 budget, which was eventually forced through on a confidence motion when BComú challenged the opposition to unite around another plan - which it failed to do.

While this experience has shown the resilience of BComú in the confrontational confines of the council chamber, the key lesson here is that occupying the institutions is not enough. An electoral strategy is not sufficient alone to create change. The power to act comes from a combination of occupying both the institutions and the squares, of social movements organizing and exercising leverage, providing social force that can be coupled with the potential of the occupied institutions - the power to change comes when these work in tandem. It’s been a bumpy ride, but BComú has been able to justify its budget on the grounds that it prioritizes social measures (such as building new nurseries, combatting energy poverty and focusing resources on the poorest neighbourhoods) with reference to the extensive and ongoing process of participation that it has encouraged.

One of the biggest dangers in looking to build radical municipalist movements in other cities is to mistake electoral victory with victory, to sit back and think that now we’ve got ‘our guys’ in the institutions, we can sit back and let change occur.

7. Transnational politics begins in your city

In a time where reactionary political movements are building walls and retreating to national boundaries, BComú is illustrating that a new transnational political movement begins in our cities.

To this end, BComú has established an international committee tasked with promoting and sharing its experiences abroad, whilst learning from other ‘rebel’ cities such as Naples and Messina. Barcelona has been active in international forums, promoting the “right to the city” at the recent UN Habitat III conference, and taking a leadership role in the Global Network of Cities, Local and Regional Governments.

These moves look to bypass the national scale where possible, prefiguring post-national networks of urban solidarity and cooperation. Recent visits of the First Deputy Mayor to the Colombian cities of Medellín and Bogotá also suggest that links are being made on a supranational scale.

One of the most tangible outcomes of this level of supranational urban organizing was the strong role played by cities in the rejection of the Transatlantic Trade & Investment Partnership (TTIP). As hosts of a meeting entitled ‘Local Authorities and the New Generation of Free Trade Agreements’ in April 2016, BComú led on the agreement of the ‘Barcelona Declaration’, with more than 40 cities committing to the rejection of TTIP. As of the time of writing, TTIP now looks dead in the water.

At this early stage, it remains unclear how this supranational network of radical municipalism may develop. Perhaps the most important step for BComú is to share their experience and support those in other cities that are looking to reclaim politics, helping to build citizens platforms across Europe and beyond. But the idea of a post-national network of citizens also allows us to dare to dream - of shared resources, shared politics and shared infrastructure - where it’s not where you were born, but where you live, that determines your right to live.

8. Essential services can be run in our common interest

The clue to BComú’s strategy for essential services is hidden in its name - the plan is to run them in common.

At the end of 2016, and faced with a crisis in the funeral sector in which only two companies controlled the sector and charged prices almost twice the national average, the Barcelona council intervened to establish a municipal funeral company that is forecasted to reduce costs by 30 per cent. Around the same time, the council voted in favour of the remunicipalisation of water, paving the way for water to be taken out of the private sector at some point this year.

In February 2017, Barcelona amended the terms and conditions for electricity supply, preventing energy firms from cutting off supply to vulnerable people. The two major energy firms - Endesa and Gas Natural - protested this by not bidding for the €65m municipal energy contracts, hoping this would force the council to overturn the policy. Instead, a raft of small and medium size energy companies were happy to comply with the new directive to tackle energy poverty, and stand to be awarded the contracts if a court challenge from the large firms proves unsuccessful. BComú is also actively planning to introduce a municipal energy company within the next two years.

However, it’s important to recognize the major difference between the public and the common. As Michael Hardt argues, our choices are not limited to businesses controlled privately (private property) or by the state (public property). The third option is to hold things in common - where resources and services are controlled, produced and distributed democratically and equitably according to peoples need. A simple example of what this could look like was the proposal - that narrowly failed only due to voter turnout - for Berlin to establish an energy company that would put citizens on the board of the company.

This difference underpins the Barcelona experience. This is not a traditional socialist government that thinks it can run things better on behalf of the people. This is a movement that believes the people can run things better on their own behalf, combining citizen wisdom with expert knowledge to solve the everyday problems that people face.

Eight lessons from Barcelona en Comú

Bellowing out in the songs of eco-village choirs and reverberating down city streets through the chants of the 99%, the call for a new economy echoes out over the dying gasps of late capitalism. From energy co-operatives in Spain that are literally bringing power to the local level, to a small school hidden deep in the English moors that is redesigning the study of economics, to a vast coalition in North America that is challenging domination by the 1%, this episode of Upstream explores the movement for a new economy. Our story begins in 1984, just outside of the G7 World Economic Summit in London, where a small group convened a counter summit to challenge the ideas and theories that dominated mainstream economics. We follow the ripples of this seminal event as they radiate out through the world and on into our current era of Trump & Brexit. This lineage traces back to the work of the renegade economist E. F. Schumacher (1911-1977). You'll hear from him, as well as many of the other people and organizations on the cutting-edge of this broad movement that is working to revolutionize the way we think about what the economy is, the way economics is taught, and the way we embody new economics in practice.

podcast, Ep 5: The Call For A New Economy by Upstream

Disabled, or just desperate?

Rural Americans turn to disability as jobs dry up

The lobby at the pain-management clinic had become crowded with patients, so relatives had gone outside to their trucks to wait, and here, too, sat Desmond Spencer, smoking a 9 a.m. cigarette and watching the door. He tried stretching out his right leg, knowing these waits can take hours, and winced. He couldn’t sit easily for long, not anymore, and so he took a sip of soda and again thought about what he should do.

He hadn’t had a full-time job in a year. He was skipping meals to save money. He wore jeans torn open in the front and back. His body didn’t work like it once had. He limped in the days, and in the nights, his hands would swell and go numb, a reminder of years spent hammering nails. His right shoulder felt like it was starting to go, too.

But did all of this pain mean he was disabled? Or was he just desperate?

He wouldn’t even turn 40 for a few more months.

An hour passed, and his cellphone rang. He picked it up, said hello and hung up - another debt collector. He rubbed his right knee. Maybe it would get better. Maybe he would still find a job.

His mother had written a number the night before and told him to call it, and he had told her he’d think about it. She wanted him to apply for disability, like she had, like his girlfriend had, and like his stepfather, whom he now saw shuffling out of the pain clinic, hunched over his walker, reaching for a hand-rolled cigarette. Spencer got out of the truck. He lit his own.

“Remember we were talking about it last night?” he asked Gene Ruby. “Remember we were talking about signing up?”

“Yeah,” said Ruby, 64.

“Remember Mama said there was a number you got to call?”

“She’s got the number,” Ruby said. “The Social Security number.”

Spencer kept asking questions. What would Social Security want to know? How often are people denied? But he didn’t mention the one that had been bothering him the most lately: Was he a failure?

“There’s a stigma about it,” Spencer said, thinking aloud. “Disabled. Disability. Drawing a check. But if you’re putting food on the table, does it matter?”

Then: “I could probably still work.”

He put his stepfather’s walker in the truck bed, got behind the wheel, started another cigarette and, pulling out of the pain clinic’s parking lot, headed for home.

The decision that burdened Desmond Spencer was one that millions of Americans have faced over the past two decades as the number of people on disability has surged. Between 1996 and 2015, the number of working-age adults receiving disability climbed from 7.7 million to 13 million. The federal government this year will spend an estimated $192 billion on disability payments, more than the combined total for food stamps, welfare, housing subsidies and unemployment assistance.

The rise in disability has emerged as yet another indicator of a widening political, cultural and economic chasm between urban and rural America.

A nation of rising disability: What’s the rate in your area?

Across large swaths of the country, disability has become a force that has reshaped scores of mostly white, almost exclusively rural communities, where as many as one-third of working-age adults live on monthly disability checks, according to a Washington Post analysis of Social Security Administration statistics.

Rural America experienced the most rapid increase in disability rates over the past decade, the analysis found, amid broad growth in disability that was partly driven by demographic changes that are now slowing as disabled baby-boomers age into retirement.

The increases have been worse in working-class areas, worse still in communities where residents are older, and worst of all in places with shrinking populations and few immigrants.

All but three of the 136 counties with the highest rates - where more than one in six working-age adults receive disability - were rural, the analysis found, although the vast majority of people on disability live in cities and suburbs.

The counties - spread out from northern Michigan, through the boot heel of Missouri and Appalachia, and into the Deep South - are largely racially homogeneous. Eighteen of the counties were majority black, but the remaining counties were, on average, 87 percent white. In the 2016 presidential election, the majority-white counties voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump, whose rhetoric of a rotting nation with vast joblessness often reflects lived experiences in these communities.

Most people aren’t employed when they apply for disability - one reason applicant rates skyrocketed during the recession. Full-time employment would, in fact, disqualify most applicants. And once on it, few ever get off, their ranks uncounted in the national unemployment rate, which doesn’t include people on disability.

The decision to apply, in many cases, is a decision to effectively abandon working altogether. For the severely disabled, this choice is, in essence, made for them. But for others, it’s murkier. Aches accumulate. Years pile up. Job prospects diminish.

“What drives people to [apply for] disability is, in many cases, the repeated loss of work and inability to find new employment,” said David Autor, an economist with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied rising disability rates. “Many people who are applying would say, ‘Look, I would like to work, but no one would employ me.’ ”

In that position now, Spencer, a slight man with luminous blue eyes, drove deeper into western Alabama. He steered through Walker County, where nearly one in five working-age adults are on disability, and into Lamar County, where the disability rate has more than doubled over the past 20 years, arriving in the town of Beaverton, population 273, where even the 55-year-old mayor is drawing a disability check.

He pulled up to a small house alongside a quiet country road, got out and looked around. There was only forest and hills and sun. “Man, I love it out here,” he said.

“Ain’t going nowhere,” Ruby agreed.

Spencer, who wears mud-caked boots and camouflage and brags of burning trash “like a proper redneck,” has grown so enamored of rural life that he’s sometimes surprised when he remembers that he spent most of his life elsewhere. He grew up just outside of Peoria, Ill., dropped out of school at 14, secured his GED, served two stints in prison for felony burglary before he turned 20 and started working roofing jobs, following other family members into manual labor, like his grandfather who built bridges, and his mother, who worked at a stove factory.

His work as a roofer had been a constant thread through his life, from one state to the next, one job to another. And so it had been again in 2005 when he followed family members to Lamar County, which is 86 percent white and 11 percent black, and was then navigating a long decline in population and manufacturing jobs - one plant moved to Mexico, another to the Dominican Republic. He nonetheless found a roofing job quickly, settling into a life that, for a time, felt as safe as it was comfortable. But then came the recession, and the uneven recovery, and jobs started drying up, and four years ago, as the county poverty rate climbed to 24 percent, the roofing company let him go.

He figured he’d find more work right away. But weeks became months, and he started doing what he calls “odds and ends” - work as a welder, a ranch hand, even a full-time garbage collector - but nothing restored the stability that had gone missing.

He opened the front door to his house. He walked past a small sign in a living room cabinet that said, “BELIEVE in the beauty of your dreams,” and into a bathroom that he had recently remodeled and where another sign said, “DON’T QUIT: Stick to the fight when you’re hardest hit; it’s when things seem worst that you must not quit.”

He had been reading a book lately about the power of positivity. He would sometimes think about it when putting in job applications, or when he was behind his house, looking at his possessions. There was the old Kia that hadn’t run in two years. The pile of aluminum cans for which he’d make 40 cents on the pound. The dozens of used tires a repair shop had paid him to haul away. He never knew what would turn out to be worth something.

He was blessed, he always tried to remind himself.

But increasingly there were days when Spencer knew he was faking a belief, once so strong, that everything would work out. There were days like today, when he sat in a pew in a small church in Lamar County, listening to members of the congregation ask for prayers for health issues:

“My mother-in-law is in the hospital this week, and she has some heart problems,” a man said.

“My body is not cooperating with my job whatsoever,” a woman said.

“I got my back surgery,” another man said. “I hope it takes this time.”

An hour later, Spencer was home again. His knee was hurting once more, as it had on and off ever since he fell from a roof during a construction job two years ago. He’d never had it checked out because he’d never had insurance, and he didn’t mention it now because everyone at the house seemed worse off than he was. His mother, Karen Ruby, 60, who has cirrhosis of the liver, was sitting at the kitchen table with her head in her hands, saying, “I don’t know when I’m going to be able to get back into church.” His stepfather was stooped beside her, next to a wheelchair, smoking a cigarette. His girlfriend, Tasha Harris, 34, a thin, ashen woman whose back was often thrown out, was upstairs in the dark after leaving church early because she hadn’t felt well.

“I need angel food cake,” his mother told him before he headed out to the store. “Write it down.”

“Angel food cake? All right, I’ll be back,” he said, walking toward the door.

“I feel like crap,” said Harris, who had come downstairs to see him off.

“I’m sorry,” Spencer quietly told her, then went outside to his truck and pulled onto the road.

This is how Spencer spends most of his days, ferrying to the dollar store and back, collecting soda, cigarettes and whatever else his family may want, and consoling them when he’s around. Most days he doesn’t mind. He likes feeling like the strong one when it seems as though almost everyone he knows is either applying for or already on disability. Just the night before, during a family dinner, it had struck him again.

“She walks, and it breaks her bones,” his cousin, who applied for disability after a nervous breakdown, had said of another relative receiving disability.

“She falls a lot,” added his aunt, who collects $733 monthly in disability checks because of back pain.

Spencer, listening to the conversation, had looked around. At the table was another cousin, who has bipolar disorder and receives $701 per month. Beside her was her boyfriend, whose mom had applied for disability, too. Spencer glanced at the ceiling and sighed.

“The whole world is on disability,” he said.

“It’s a tough world,” someone else said.

And now that world was spread out before him as he drove through downtown Beaverton, past a value store, a post office that closes at noon, a bank that shuttered during the recession, a gas station that hasn’t been open for as long as Spencer has been here.

He saw a large roadside banner that said, “APPLY NOW IMMEDIATE OPENINGS,” and cursed to himself. He didn’t know how many times he’d gone in that upholstery factory and asked about a job, any job, and was turned away. He saw another factory, this one an equipment supplier, where he thought he’d need an act of Congress to get hired. Up ahead was a horse-trailer shop. Three consecutive months he had gone through the door, and each time they’d said, “Next month, try us.” Meanwhile, he tried to sign up for a welding class at a community college, but failed the enrollment math exam.

He pulled up to the Piggly-Wiggly. He collected cake mix and three 12-packs of Mountain Dew for Harris, who he knows can go through 24 cans in a day, and was driving home, passing everywhere he couldn’t get a job, when he thought of another opportunity. There was still that place that might need help with welding, a skill he’d picked up after he lost his roofing job. He had told himself he’d go first thing on Monday morning. Arrive by 8:30 a.m. Show the enthusiasm and dedication of someone worth hiring.

Walking back into his house, he placed the cake mix on the counter and heard his mother, who was in her room, with the curtains drawn and the television on, holding an unlit cigarette.

“Desmond?” she said, her voice raspy from a case of strep throat. “Is that black lighter in there?”

“Black lighter?” he said.

“I got a sore throat,” she said.

“I don’t see it,” he said of the lighter.

“Me and Gene, neither of us got a lighter now,” she said.

He began placing empty soda cans into a plastic bin and clearing the kitchen table of the dishes from the night before, then heard Harris at the bottom of the steps.

“Baby?” she said. “My head is still killing me.”

“I got you something for your headache,” he said, handing her some medicine and a 12-pack of Mountain Dew, and went back to the kitchen.

“Desmond,” Harris softly called after him.

“Yeah?” he said, returning.

“Do you have a cigarette?”

He gave her one, finished with the kitchen, then limped to the living room. He lowered himself onto the couch, his knee hurting worse than earlier, and flipped on the television.

Something had to change.

Everyone in his life has been telling him what that something is.

You’re hurting more and more, his mother said. And not getting any younger.

There aren’t jobs for you here, a friend said. Think that’ll change anytime soon?

We all need help now and again, his girlfriend said. Don’t be ashamed of being on disability.

You’re a grown man, his stepfather said. Bring in some money.

That was what Spencer was thinking about - money, and not having any - when one day Harris found him sitting alone on the back porch in the quiet, going through another cigarette. “Checks are in,” she said of his parents’ monthly disability payments, which are cumulatively worth $3,616 and support everyone in a house that, at that moment, was low on just about everything.

“We’re going to the store,” Harris said.

“How you getting there?” he asked.

“The truck.”

“It ain’t got no gas, though.”

“I got to take your mom to the bank.”

“Maybe she’ll loan you 10 for gas.”

Harris disappeared back into the house, and Spencer went back to his cigarettes and thoughts. It didn’t seem right to him, living off his parents’ disability checks and borrowing money from them. But he felt trapped. He couldn’t leave Lamar County with his mother so sick. And the only money he had coming in was the monthly $425 an elderly friend paid him to tend his horses and keep him company on lonely afternoons, and it was never enough to cover everything. This month it was socks. Harris needed socks. And what kind of man can’t afford socks? His grandfather used to tell him that a man isn’t a man unless he owns land, and now here he was, years later, not feeling like one at all.

He found Harris in the kitchen. “Ask him for $40,” she told him. “And I’ll get 10 more from him to buy socks.”

Gene Ruby was at the computer when Spencer approached him. The question came quickly and quietly. “Could I borrow 40? And give it back to you right here soon?” he asked. “I promise.”

A few hours after pocketing the money, Spencer climbed back into the truck Gene made the payments on and started it with the gas Karen had paid for. Harris got in beside him. They had been together for seven years and rarely disagreed, except for that day two years before when Harris said she was thinking of applying for disability on account of back pain. He told her not to do it. People would look down on them. They would find jobs. Don’t lose hope.

A light blinked on the dashboard.

“Transmission’s hot,” Harris said. “I told you it did that to me the other day.”

He pressed down on the accelerator.

“No, don’t do that,” she said. “Just put it in neutral and coast. Try not to mash the gas at all.”

“We’re running it into the ground, is what we’re doing,” he said, lighting another cigarette.

Harris looked at him. She could tell he was getting frustrated. Just about everything these days made him that way. He had begun complaining more, not just about the truck or the pain in his knees and hands, but about all of Lamar County. He told her there would never be jobs here for them. Maybe she had been right about applying for disability. His injuries weren’t getting better, and he wasn’t getting hired, and how much longer could he ask for help with groceries? Help with gas? Help with transportation? Help with everything?

He moved the truck out of neutral and back into drive. The store was 20 miles up the road in Hamilton, the largest town in the area, with a population of 6,814. Harris’s brother and his wife lived on its outskirts, and in the falling light, they went to visit, pulling up to a tidy mobile home set beside a large field. Harris’s sister-in-law, Chastity, who was working full time at a calling center, came outside. Then followed Harris’s brother, Josh, 28, broad-shouldered and shirtless. They handed a plate of barbecue pork to Spencer and Harris, both of whom had skipped lunch that day. The plate went back and forth between them.

“I just went and got a job at Wrangler,” Josh said of a distribution center in nearby Hackleburg.

Spencer stopped eating. He looked up.

“Is that right, man?” Spencer asked, and Josh nodded. “That’s great. I’m proud of you. Man, I’m happy about that. I’m happy you got that.”

“Me, too,” Josh said. “It pays good.”

“Monday, I’m going to go back to that shop where . . . I heard they need help,” Spencer said. “Hopefully, I can weasel my way in there.”

“You can,” Josh said. “Put it in your mind, and you can do it.”

“I had an inspiration book,” Spencer said. “You wake up and put it in your head: ‘God’s got my back. I got this job.’ ”

There was a moment of quiet.

“I’m glad you got that, man,” Spencer said again. “I’m proud of you.”

“Sometimes, it’s just the right place at the right time.”

Spencer and Harris finished the barbecue, hugged their relatives goodbye and got back into the truck. He drove to a strip mall that had a Shoppers Value Foods, a Check Into Cash and a title loan shop. He glanced at a sign outside a Sonic fast-food restaurant: “Now Hiring All Shifts.” He sometimes considered applying for a fast-food job. But how, after making $20 an hour at some jobs, could he take one paying $7.25?

He parked and went inside the grocery store.

Spencer was looking at a piece of paper on the coffee table. It was the number to the Social Security office his mother had given him. He and Harris sat on the couch in the living room, and she handed him a telephone.

“You got to call,” she said.

“I’m nervous,” he said.

“Don’t be nervous,” she said. “They’re not going to reach through the phone and get you.”

He didn’t say anything for a moment, just held the phone.

“What do I do and say?” he asked.

“Call that number and do whatever they tell you to do.”

He took in a breath and exhaled slowly.

“I guess I’ll call,” he said, punching in the number, and then came a voice on the other end, with that question again, the one he rarely had the courage to ask himself:

“Are you disabled?”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said.

“How long have you been disabled?”

“Two years.”

“How are you supporting yourself?”

“Living off my mom.”

“Is this a permanent disability?”

“Uhh,” he began. “I don’t think . . . ”

He looked at the floor and leaned forward.

“Yeah,” he said quietly. “Yeah, I don’t think it’s getting no better.”

He scheduled an appointment for an interview at the local Social Security office the following month. He hung up, stood and, appearing dazed, told Harris, “I didn’t like it at all.” She gave him a sympathetic look and left him alone on the couch.

He was there again four days later on a Monday morning.

The entire house was dark. Spencer was in his pajamas, watching television. Harris was soon beside him, also in pajamas. “I think I’m getting sick,” she said, and he didn’t answer. She went to another room and came back with Ruby’s laptop, which she uses every Monday morning to look at job listings.

“I ain’t checked it in a week,” she said.

“Oh my God,” he sighed, flipping through channels.

“Do you know anything about pop-ups?” she asked, looking at the computer. “Man, I’ve had, like, a hundred pop-ups.”

“Look, the new ‘Walking Dead,’ ” Spencer said, coming to another channel.

She pulled up her email and clicked on one that listed service positions within 25 miles. “Okay,” she said. “Here we go.” She saw three postings: “Customer Service/Telecommute,” “Telecommute Consultant” and “Product Tester.” She didn’t investigate any of them, instead going back to her inbox. She found another email with more listings.

“Erber?” she asked. “We don’t even have an Erber place around here.”

“Uber,” Spencer said.

“Uber, Erber, whatever,” she said, closing the computer.

An hour passed, then another, and Spencer stayed on the couch. He would not apply for the welding job today. He wanted to focus on securing disability.

“I got to go get dressed,” he said, looking down at his clothing. “What a loser.”

He returned in torn jeans and, with nothing better to do, went outside. He limped to the truck and fiddled with jumper cables. He set a fire inside an iron bin and burned some trash. He inspected a sheet of aluminum he had found, wondering how much he could sell it for. He walked into the woods and walked out. He looked at the road. A car hadn’t passed in a long while. It was 1 in the afternoon. The day already felt over.

Disabled, or just desperate?

U.S. College Grads See Slim-to-Nothing Wage Gains Since Recession

Petroleum engineers and philosophy majors are bucking the trend

The bachelor's degree - long a ticket to middle-class comfort - is losing its luster in the U.S. job market.

Wages for college graduates across many majors have fallen since the 2007-09 recession, according to an unpublished analysis by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce in Washington using Census bureau figures. Young job-seekers appear to be the biggest losers.

What you study matters for your salary, the data show. Chemical and computer engineering majors have held down some of the best earnings of at least $60,000 a year for entry level positions since the recession, while business and science graduates's paychecks have fallen. A biology major at the start of their career earned $31,000 on an annual average in 2015, down $4,000 from five years earlier.

"It has been like this for the past five, six years now," said Ban Cheah, a research professor at Georgetown who compiled the data. "It's a little depressing."

The outlook for experienced graduates, aged 35 to 54, is brighter, with wages generally stable since the crisis.

The economic premium of a bachelor's flattened after the recession, according to a 2016 National Bureau of Economic Research paper by Robert Valletta, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Among the factors at play are advances in technology and automation, which are not only taking away U.S. manufacturing jobs, but also having an impact on white collar workers, Valletta found. Legal clerks and researchers are increasingly finding their jobs supplanted by computers, for example.

Some majors are bucking the wage-stagnation trend. An experienced petroleum engineering major earned $179,000 a year on average in 2015, up $46,000 from five years prior, according to the Georgetown analysis. Beyond those with special technical skills, philosophy and public policy majors have also seen their earnings rise.

So how can you boost your career earnings potential? A graduate's level degree is increasingly offering the bigger salary bump, according to Cheah. The wage gap between graduate degree-holders and undergrads has been growing, he said.

It's also important to remember that a student's major is just one determinant of their future earnings potential. The training experience from internships, debt levels and soft skills also help shape salary and job prospects, said Jeff Selingo, who writes about higher education and is a professor of practice at Arizona State University.

"Just getting a degree doesn't matter anymore," said Selingo. "What matters more are the undergraduate experiences that you have."

U.S. College Grads See Slim-to-Nothing Wage Gains Since Recession

Underemployment of young people is the highest it has been in 40 years

Almost one in five young people have fewer hours of work than they want, with underemployment in the youth labour force at its highest level in 40 years.

When unemployment is taken into account, the proportion of people aged 15 to 24 who are either without work or enough hours of work is now at 31.5 per cent.

The so-called "under-utilisation rate" which combines unemployment and underemployment levels is higher than it was during the 1990s recession.

Josh Sandman, 19, is one of 659,000 young Australians who are either unemployed or underemployed - having some work, but wanting more hours.

He does 10 hours a week of volunteer work as a freelance graphic designer in the hope it will lead to a full-time job. He had about 20 hours a week of paid work at a takeaway food outlet in Adelaide until a couple of weeks ago.

"If I had lost my job and was not living at home I would be on a couch or homeless right now," he said.

The new Brotherhood of St Laurence analysis shows 18 per cent of young people are underemployed, the highest level it has ever been since 1978 when the Australian Bureau of Statistics first started collecting the data.

Underemployment is now much higher than youth unemployment which is at 13.5 per cent.

Unemployment was less than 10 per cent and underemployment was at 11 per cent just before the global financial crisis.

The new analysis uses data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey and the Department of Employment.

To be released on Monday, the Brotherhood of St Laurence publication, Generation Stalled: young underemployed and living precariously in Australia has found that the rise of underemployment can not be explained by the growing number of young people combining study with work.

"[T]he rise in the percentage of casual and part-time jobs has mostly been among young workers who are not studying," the report says.

Young people are now far more likely to be in casual and part-time jobs now than they were in the year 2000. The gap between the actual hours worked and the hours young people want to work has widened.

"The employment outlook for many young Australians today is profoundly different than it was when their parents and grandparents first started work," said Tony Nicholson, executive director of the Brotherhood of St Laurence.

"The record growth of underemployment particularly hurts the 60 per cent of young people who don't go to university - they face a much more uncertain future than previous generations."

Mr Nicholson said in the past, young people could leave school early and get a job in a factory, mail room, bank or a state-owned enterprise get training and improve their prospects.

"They had every chance to build a good life for themselves and their families. These opportunities have shrunk as the economy has changed and insecure jobs are leading to far more uncertain prospects for the new generation," he said.

"We need to redouble our efforts to build the capabilities of disadvantaged young people in this very challenging scenario. Tinkering with welfare payments is not the answer here."

The prevalence of young workers who are not students on permanent contracts has fallen from 61.8 per cent in 2008 to 53.2 per cent in 2014.

The proportion of students in casual work has fallen in recent years.

Underemployment of young people is the highest it has been in 40 years

Eight lessons from Barcelona en Comú

On 24 May 2015, the citizen platform Barcelona en Comú was elected as the minority government of the city of Barcelona. Along with a number of other cities across Spain, this election was the result of a wave of progressive municipal politics across the country, offering an alternative to neoliberalism and corruption.

After 20 months in charge of Barcelona, here are eight things we have learned from Ada Colau and Barcelona en Comú.

With Ada Colau - a housing rights activist - catapulted into the position of Mayor, and with a wave of citizens with no previous experience of formal politics finding themselves in charge of their city, BComú is an experiment in progressive change that we can’t afford to ignore.

After 20 months in charge of the city, we try to draw some of the main lessons that can help inspire and inform a radical new municipal politics that moves us beyond borders and nations, and towards a post-capitalist world based on dignity, respect and justice.

1. The best way to oppose nationalist anti-immigrant sentiment is to confront the real reasons that life is shit

There is no question that life is getting harder, more precarious, more stressful, and less certain for the majority of people. In the US and across Europe, reactionaries, racist and nationalist politicians are blaming this on two things - immigrants, and ‘outside forces’ that challenge national sovereignty. Whilst Trump and Brexit are the most obvious cases, we can see the same phenomenon across Europe, ranging from the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany through to Front National in France.

In Barcelona, there is a relative absence of public discourse that blames the social crisis on immigrants, and most attempts to do so have fallen flat. On the contrary, on 18 February over 160,000 people flooded the streets of Barcelona to demand that Spain takes in more refugees. Whilst this demonstration was also caught up with complexities of Catalan nationalism and controversy over police repression of migrant street vendors, it highlighted the support for a politics that cares for migrants and refugees.