Neoliberals Too Busy with Orange Mutant to Notice Angry-Hungry Peasants with Pitchforks.

For 2017: Endless Class Warfare. Racist Robots Stealing American Jubs. And Griefstriken Unber Wealthy on Welfare to Overcome Orange horror.

In 2017, Fusing Identity and Class Politics in “Trumpland”

Like millions of other Americans, I was shocked, but perhaps not entirely surprised, by Donald Trump’s victory on election night. His blatant racism and misogyny, cynical exploitation of economic populism, and ties to fascist ideology have generated enormous fears. Yet if we stop at the point of those fears, and let fatalism or blame games drive our response to the Trump regime, then we have already ceded our power to him.

Yes, Trump carries the whiff of fascism, and many of his followers indeed hold racist and misogynist beliefs. But we cannot stop thinking at that point. We should begin to ask ourselves: if we lived in Europe during the rise of fascism in the 1920s or early 1930s, what would we actually do to stop it? In that era many progressives were defending tepid establishment politics, and radicals were making boring speeches, while the fascists were forming chorale groups, hiking societies, and theater troupes to reach and inspire people on an emotional level.

The European left at that time didn’t effectively speak to large numbers of working-class and middle-class citizens, particularly in small towns and cities, and created a vacuum that the far-right was all too eager to fill. In fear of alienating the majority, leftists also failed to defend the rights of Jews, Gypsies, and others who were targeted as the economic scapegoats for the Depression. They failed to have a sense of their own power and their ability to go on the offensive, and went into a reactive mode, defining themselves by what they were against rather than what they were for.

We can see these trends today, as many white progressives propose stepping back from defending so-called “identity politics,” in order to gain more votes from the white, straight majority. Many progressives and radicals likewise seem to be stepping back from class-based “unity politics,” by writing off huge areas of the country’s interior as a backward and hopeless “Trumpland.” Both knee-jerk reactions are enormous, strategic movement-killers at this moment in history.

The ascribed identities of race, ethnicity, and gender, and the achieved status of economic class, have always been inseparable this country’s history. Whether your politics are centered primarily on racial, ethnic, or gender identities, primarily on economic inequalities, or hopefully on both, our common enemy is the white elites from both parties who currently hold power.

“Identity politics” (or particularism) and “unity politics” (or universalism) are not mutually exclusive, and do not have to detract from each other. To clip either wing of our movement is to cripple its ability to fly, and fails to recognize-as Bernie recognized midway through his campaign-that both identity and economic messages can be strengthened at the same time. But in order to do so, we need to recognize our existing strengths, and expand the geographical scope of our social movements into unlikely places.

Our Strengths

First, we should become more confident of the strengths that we have in January 2017, (despite Trump’s Electoral College victory), and compare them to January 2001, when Bush came to power under similar clouded circumstances. Back then, the only recent mass movement that had united different constituencies was the opposition to the World Trade Organization, and the WTO protests in Seattle had only occurred a year before. We weren’t prepared for Bush’s war on civil liberties and Iraq, partly because our capacities were so low.

In contrast to January 2001, we are far more prepared in January 2017. Since then, we’ve had under our belts the antiwar movement, Occupy, climate justice, marriage equality, Black Lives Matter, the Bernie campaign, and Idle No More (expressed most recently at Standing Rock). We weren’t as resilient then against Bush and 9/11 as we are now against Trump and whatever comes next.

We now have far more young people with movement experience, hooked up with each other through social media. Polls show that demographics are in our favor, with younger people far more critical of capitalism and accepting of a diverse society than previous generations. The future looks bright-it’s just the present that sucks. History may view Trump as the last gasp of the racist and misogynist dinosaurs, but only if we view ourselves as the comet that finally wipes them out.

Rural Challenges

Second, the election confirmed our need to confront urban-rural divides in the country like never before. As a geographer, I’d highlight the New York Times map that shows the Democratic vote as a limited “archipelago” along the coasts (with some interior cities and college towns), and the country’s vast interior as a Republican “sea.” It may be easy for urbanites to blame white racial homogeneity, but even some relatively diverse interior areas voted for Trump (in Washington, for example, Republican Yakima County is more diverse than my Democratic city of Olympia). In seeing how we got to this point, let’s examine Wisconsin and Iowa, both states with many rural counties that voted twice for Obama, but went this time for Trump.

Rural Democrats in Wisconsin begged their party leaders in Madison for yard signs, but were told the campaign funds had to be put into TV ads. Hillary Clinton failed to visit Wisconsin even once, and her campaign rebuffed Obama when he volunteered to stump for her in Iowa. The urban-based Party’s arrogant and elitist decisions created a Democratic vacuum in rural areas, isolating its own supporters. The resulting “sea” of Republican yard signs swayed undecided voters with an illusion of their neighbors’ consensus, in counties that actually voted only narrowly for Trump.

Again, asking the question about what could have been done in Europe during the rise of fascism, we have to look to U.S. models that have actually included rural whites in a common cause with marginalized communities. There is perhaps no better example than the Cowboy Indian Alliance, which has so far blocked the Keystone XL Pipeline in the deep-red states of South Dakota and Nebraska. The unlikely alliance combined the treaty rights of Indigenous nations with the populist grievances of their historic enemies: white farmers and ranchers. People power fused identity and economic values, and strengthened Native sovereignty, by defending the land and water from corporate power.

The leader who brought forward the Cowboy Indian Alliance name from earlier groups was Faith Spotted Eagle, an Ihanktonwan Dakota elder who more recently fought the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock. On December 19, Washington Puyallup elector Robert Satiacum gave his vote to Spotted Eagle for president, and to Ojibwe activist Winona LaDuke for vice president. Their names came up in my conversation with Robert a month before, partly because they were Indigenous women leaders fighting oil pipelines, and also because they had built bridges with rural whites. Their most effective approach for cross-cultural organizing has been through social movements, rather than electoral politics, and they will continue the fight under Trump.

As Faith Spotted Eagle said in 2014, “The model of capitalism is trying to suffocate us, because with capitalism you need an underclass. Capitalism cannot survive without poor farmers, without poor Indians, without poor people in the cities who are selling their souls.” When Keystone XL was blocked in 2015, she commented, “We stood united in this struggle, Democrat, Republican, Native, Cowboy, Rancher, landowners, urban warriors, grandmas and grandpas, children, and through this fight against KXL we have come to see each other in a new better, stronger way.”

The Cowboy Indian Alliance was not a fluke, but part of a rich tradition of rural social movement organizing. Community organizers in the South have opposed Klan and police violence, and point out that social programs won by the civil rights movement have also benefited rural whites. Groups such as the Rural Organizing Project in Oregon and Northern Plains Resource Council in Montana are trying to fill the void, but need more funding and resources to compete with far-right politicians and militias for the hearts and minds of rural whites. The success of such alliances fighting for justice and the land weakens the appeal of racist groups fighting against economic scapegoats.

Potential in Small Cities

Third, the election also exposed how our movements have become over-reliant on large urban areas. Progressive/radical movements have long been concentrated in particular urban neighborhoods, and college towns such as Madison, Berkeley, and Olympia. In large cities, movements possess a critical mass to hold large rallies, staff and fund organizations, and create intersectional ties between communities. But if these positive advances do not spread or reverberate in places where movements have fewer people and resources, they will not change the country as a whole, but reinforce the divides in our country.

This is not a criticism of urban-based movements, since historically social change has begun in large cities, but a criticism of keeping social change isolated in “safe” progressive enclaves. On one hand, some white progressives may feel more comfortable in a neighborhood with Co-Exist bumperstickers and Tibetan prayer flags, and activists of color may feel more comfortable in a large city than to support their counterparts in smaller communities. Yet on the other hand, we may come to realize that capitalism needs these enclaves. They keep radicals and progressives cloistered, talking only with each other, and not influencing or learning from other people.

It is a huge mistake for urban progressives and radicals to view rural areas or smaller cities as cultural-political wastelands, and create a vacuum that cedes these areas to the far-right. Just as identity and economic politics are not mutually exclusive, urban and rural organizing can work hand-in-hand. We can use our more open cities and neighborhoods as a base, but also stand in solidarity with movements outside them. For example, Olympia activists recently blockaded a train carrying oil fracking materials to North Dakota, and Minneapolis activists hung a NoDAPL Divest banner at a televised NFL game. We can also understand that the sparks of mass movements sometimes occur in smaller communities, such as Ferguson or Standing Rock, and not assume that urban activists have all the answers.

The greatest potential growth for our movements may not be in either large cities or rural areas. In large cities, residents have generally been exposed to social movements, even if only by seeing headlines or riding past a rally, and have ample opportunities to express their views. On the other hand, residents of small rural towns are often afraid of rocking the boat, and being ostracized by their neighbors, so any movement growth there is bound to be slow and incremental.

But it is in small- and medium-sized cities where the battle for the heart and soul of America is taking place-in cities such as LaCrosse, Wis., Flint, Mich., or York, Pa. There is room for the movement to grow in these “in-between” places, for people to begin to express their views and find limited safety in numbers. But there is not enough support for groups doing the slow, unglamorous work of education and organizing in these smaller cities, where every small rally or leaflet actually counts.

Here in Washington state, for example, the hotspots for the fossil fuel wars have been smaller working-class cities, such as Aberdeen and Hoquiam, where residents have been fighting the proposed Grays Harbor oil terminal. Seattle-based environmental groups are not as successful in mobilizing residents of these former timber towns as local, frontline organizers. Smaller towns and cities such as Forks and Kelso have similarly become frontlines for immigrant rights organizers.

More resources and funds should be directed toward these communities, not only in episodic responses to police shootings or environmental threats, but to steadily build the capacities of local organizers. In Eau Claire, Wis., for example, social movements languished for years after local factories were shut down. But then community members put their energies into starting cooperatives and coffeehouses, working with student groups on the small branch college campus, and building a low-power community radio station. The new artistic venues generated a vibrant music and political scene, and the county stayed blue as the others in western Wisconsin turned red.

Building Hope in Unlikely Places

Our movements need both the depth we develop in large cities through activism among the already-aware residents, and the breadth we develop by diffusing progressive ideas outside the echo chamber, using grassroots education and organizing. By shifting resources to smaller communities, and enlarging our base beyond the progressive enclaves, we need to develop faith in the ability of people to change their views and actions. Urban residents often believe and internalize fixed stereotypes of people from smaller communities as simply “hicks” or “rednecks,” and thereby dismiss these places from the start.

Spanish is better suited than English when describing people and their beliefs. English only has one verb for “to be,” but Spanish verbs differentiate fixed identity from actions. People “are” (ser) a certain type of person, but also “are being” (estar) a certain way. When we hear the racism and misogyny of many Trump voters, we can assume they are (ser) racist, without seeing that the media and educational system have failed to educate them. We can also view them as being (estar) racist against people below them in the social hierarchy, and help redirect their anger against the white elites above them that are the actual source of their problems.

We can begin by switching in our minds from using ser to using estar, to see the possibilities of reaching and organizing unlikely people in unlikely places -particularly if we are from these places. We can try to communicate with our friends, family, and citizens who are attracted to the right-populist message, and offer a left-populist alternative they may not yet have heard in the business-as-usual morass of lies and commercialism.

There is potential hope in everyone, because everyone can change their opinions over time and with events. Social change is all about people changing their minds, and being inspired to act. If we assume their views are permanently fixed, we have already given up on making change. If we assume their views can shift, and they might have something to fight for alongside communities other than their own, we open up more possibilities for hope. In this way, we can enlarge the Rebel Alliance against the Empire.

In 2017, Fusing Identity and Class Politics in “Trumpland”

The Racial Wealth Divide in America Is Staggering-and That's Before Trump Walks into the White House

White households possess roughly 13 times the wealth of their black counterparts.

After predicating his presidential campaign on racist incitement against Muslims, immigrants and Black Lives Matter, President-elect Donald Trump set to work appointing a cabinet that, so far, is setting new records as the wealthiest, and least diverse, in American history. In less than a month, that administration will take the White House of a country that faces the highest levels of wealth disparities along racial lines in nearly three decades.

The Pew Research Center determined in June that white homes possess roughly 13 times the wealth of their black counterparts. Analysis of federal government data also determined that black people in the United States are at least two times as likely as white people to be poor or unemployed. Meanwhile, homes headed by a black person “earn on average little more than half of what the average white households earns,” Pew concluded.

A separate Pew report concluded in 2014 that the wealth gap between white and black people in the United States is at its highest point since 1989.

Those findings were followed by a separate report released in August by the the Institute for Policy Studies and the Corporation for Enterprise Development found that, if economic trends over the past three decades continue on pace, it “will take black families 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth white families have today.” It would take Latino families 84 years to accrue the same wealth as their white counterparts.

The study projects that, by 2014, when people of color are projected to comprise a majority of the U.S. population, the wealth divide with white families on one side and Latino and black families on the other will be double current levels.

“This growing wealth divide is no accident,” states the report. “Rather, it is the natural result of public policies past and present that have either been purposefully or thoughtlessly designed to widen the economic chasm between white households and households of color and between the wealthy and everyone else. In the absence of significant reforms, the racial wealth divide-and overall wealth inequality-are on track to become even wider in the future.”

This economic divide dovetails with racial segregation on the neighborhood level. A report authored by Century Foundation fellow Paul Jargowsky in 2015 found that “more than one in four of the black poor and nearly one in six of the Hispanic poor lives in a neighborhood of extreme poverty, compared to one in thirteen of the white poor.”

"Through exclusionary zoning and outright housing market discrimination, the upper-middle class and affluent could move to the suburbs, and the poor were left behind," he writes. "Public and assisted housing units were often constructed in ways that reinforced existing spatial disparities. Now, with gentrification driving up property values, rents, and taxes in many urban cores, some of the poor are moving out of central cities into decaying inner-ring suburbs."

Impacted communities have long been sounding the alarm about this trend. In their policy platform released earlier this year, the Movement for Black Lives proclaimed, “We demand economic justice for all and a reconstruction of the economy to ensure black communities have collective ownership, not merely access.”

The platform states, “Together, we demand an end to the wars against black people. We demand that the government repair the harms that have been done to black communities in the form of reparations and targeted long-term investments. We also demand a defunding of the systems and institutions that criminalize and cage us.”

The Racial Wealth Divide in America Is Staggering-and That's Before Trump Walks into the White House

This Is the Year Economists Finally Figured Out What Everyone Else Long Understood About 'Free Trade'

The trade deals they shilled for didn’t work out all that well.

This week, Bloomberg’s Noah Smith published a list of “ten excellent economics books and papers” that he read in 2016. Number three on his list was the now celebrated paper, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” by economists David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson. Here’s Smith’s summary of the work and its consequences:

This is the paper that shook the world of economics. Looking at local data, Autor et al. found that import competition from China was devastating for American manufacturing workers. People who lost their jobs to the China Shock didn’t find new good jobs-instead, they took big permanent pay cuts or went on welfare. The authors also claim that the China Shock was so big that it reduced overall U.S. employment. This paper has thrown a huge wrench into the free-trade consensus among economists.

Smith’s account of the paper’s effect is absolutely right: Economists’ astonishment and dismay at Autor & Company’s revelations were palpable and widespread. Which raises a question many of us have been raising for years: Why have mainstream economists been the last people to understand the consequences of the policies they advocate? During the debate that swirled around the congressional legislation granting permanent normal trade relations to China in 1999 and 2000, unions, progressive think tanks (most especially the Economic Policy Institute), and other liberal groups predicted with unerring accuracy the job loss that would follow if PNTR was enacted, the concomitant failure to generate adequate replacement jobs, and in a few cases, even the political shifts likely to follow in the states of the rapidly deindustrializing Midwest-shifts that did not fully manifest themselves until this November. But to the high priests of mainstream economics, and to the Robert Rubins and Timothy Geithners who provided policy guidance to the Bill Clinton and Barack Obama administrations, these were fringe opinions, narrowly self-interested, and not worthy of serious consideration.

Well, yes-the industrial Midwest was self-interested; its residents had an understandable reluctance to seeing their economies dismantled and their middle-class decimated.

The lesson from all this is that mainstream economics has to be viewed less as an empirical, much less scientific, discipline, and more as an elegant regurgitation of the worldview of dominant financial powers. By endorsing the efficiency of markets and the concomitant curtailment of regulation, by assuming that trade with industrializing, poverty-wage mega-nations would not have a devastating impact on American manufacturing workers, by a thousand other deaths of common sense, the American economic mainstream reduced itself to little more than a priesthood serving the gods of Wall Street. The dissents of dissident economists-from Joe Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik to Dean Baker, Jared Bernstein, and the gang at EPI and Global Trade Watch, from Thea Lee at the AFL-CIO to Mark Levinson at the clothing and textile workers unions and Clyde Prestowitz at his own institute, from the pages of The American Prospect to the pages of, well, The American Prospect-were drowned in propaganda masquerading as economics.

Now that the jobs have fled, now that the deregulation has led to an epochal collapse and a woefully selective recovery, the masquerade is over-or rather, should be over. The whole point of Trickle Downers is to hasten it to its long overdue end.

This Is the Year Economists Finally Figured Out What Everyone Else Long Understood About 'Free Trade'

iPhone manufacturer Foxconn plans to replace almost every human worker with robots

China’s iPhone factories are being automated

Foxconn, the Taiwanese manufacturing giant behind Apple’s iPhone and numerous other major electronics devices, aims to automate away a vast majority of its human employees, according to a report from DigiTimes. Dai Jia-peng, the general manager of Foxconn’s automation committee, says the company has a three-phase plan in place to automate its Chinese factories using software and in-house robotics units, known as Foxbots.

The first phase of Foxconn’s automation plans involve replacing the work that is either dangerous or involves repetitious labor humans are unwilling to do. The second phase involves improving efficiency by streamlining production lines to reduce the number of excess robots in use. The third and final phase involves automating entire factories, “with only a minimal number of workers assigned for production, logistics, testing, and inspection processes,” according to Jia-peng.

The slow and steady march of manufacturing automation has been in place at Foxconn for years. The company said last year that it had set a benchmark of 30 percent automation at its Chinese factories by 2020. The company can now produce around 10,000 Foxbots a year, Jia-peng says, all of which can be used to replace human labor. In March, Foxconn said it had automated away 60,000 jobs at one of its factories.

In the long term, robots are cheaper than human labor. However, the initial investment can be costly. It’s also difficult, expensive, and time consuming to program robots to perform multiple tasks, or to reprogram a robot to perform tasks outside its original function. That is why, in labor markets like China, human workers have thus far been cheaper than robots. To stay competitive though, Foxconn understands it will have to transition to automation.

Complicating the matter is the Chinese government, which has incentivized human employment in the country. In areas like Chengdu, Shenzhen, and Zhengzhou, local governments have doled out billions of dollars in bonuses, energy contracts, and public infrastructure to Foxconn to allow the company to expand. As of last year, Foxconn employed as many as 1.2 million people, making it one of the largest employers in the world. More than 1 million of those workers reside in China, often at elaborate, city-like campuses that house and feed employees.

In an in-depth report published yesterday, The New York Times detailed these government incentivizes for Foxconn’s Zhengzhou factory, its largest and most capable plant that produces 500,000 iPhones a day and is known locally as “iPhone City.” According to Foxconn’s Jia-peng, the Zhengzhou factory has some production lines already at the second automation phase and on track to become fully automated in a few years’ time. So it may not be long before one of China’s largest employers will be forced to grapple with its automation ambitions and the benefits it receives to transform rural parts of the country into industrial powerhouses.

There is, however, a central side effect to automation that would specifically benefit a company like Foxconn. The manufacturer has been plagued by its sometimes abysmal worker conditions and a high rate of employee suicide. So much so in fact that Foxconn had to install suicide netting at factories throughout China and take measures to protect itself against employee litigation. By replacing humans with robots, Foxconn would relieve itself of any issues stemming from its treatment of workers without having to actually improve living and working conditions or increase wages. But in doing so, it will ultimately end up putting hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people out of work.

iPhone manufacturer Foxconn plans to replace almost every human worker with robots

Finland trials basic income for unemployed

Government hopes two-year social experiment will cut red tape, reduce poverty and boost employment

Finland has become the first country in Europe to pay its unemployed citizens an unconditional monthly sum, in a social experiment that will be watched around the world amid gathering interest in the idea of a universal basic income.

Under the two-year, nationwide pilot scheme, which began on 1 January, 2,000 unemployed Finns aged 25 to 58 will receive a guaranteed sum of €560 (£475). The income will replace their existing social benefits and will be paid even if they find work.

Kela, Finland’s social security body, said the trial aimed to cut red tape, poverty and above all unemployment, which stands in the Nordic country at 8.1%. The present system can discourage jobless people from working since even low earnings trigger a big cut in benefits.

“For someone receiving a basic income, there are no repercussions if they work a few days or a couple of weeks,” said Marjukka Turunen, of Kela’s legal affairs unit. “Working and self-employment are worthwhile no matter what.”

The government-backed scheme, which Kela hopes to expand in 2018, is the first national trial of an idea that has been circulating among economists and politicians ever since Thomas Paine proposed a basic capital grant for individuals in 1797.

Attractive to the left because of its promise to lower poverty and to the right - including, in Finland, the populist Finns party, part of the ruling centre-right coalition - as a route to a leaner, less bureaucratic welfare system, the concept is steadily gaining traction as automation threatens jobs.

A survey last year by Dalia Research found that 68% of people across all 28 EU member states would “definitely or probably” vote in favour of some form of universal basic income, also known as a citizens’ wage, granted to everyone with no means test or requirement to work.

In a referendum last year 75% of Swiss voters rejected a basic income scheme, but that proposal - to give every adult an unconditional minimum monthly income of SFr2,500 (£1,980) - would have meant increasing welfare spending from 19.4% to around a third of the country’s GDP, and did not have government backing.

Basic income experiments are also due to take place this year in several cities in the Netherlands, including Utrecht, Tilburg, Nijmegen, Wageningen and Groningen. In Utrecht’s version, called Know What Works, several test groups will get a basic monthly income of €970 under slightly different conditions.

One will get the sum as unemployment benefit, with an obligation to seek work - and sanctions - attached. Another will get it unconditionally, whether or not they seek work. A third will get an extra €125 providing they volunteer for community service. Another will get the extra €125 automatically, but must give it back if they do not volunteer.

The Italian city of Livorno began giving a guaranteed basic income of just over €500 a month to the city’s 100 poorest families last June, and expanded the scheme to take in a further 100 families on 1 January. Ragusa and Naples are considering similar trials.

In Canada, Ontario is set to launch a C$25m (£15m) basic income pilot project this spring. In Scotland, local councils in Fife and Glasgow are looking into trial schemes that could launch in 2017, which would make them the first parts of the UK to experiment with universal basic income.

The Green party in the UK has supported the idea of a citizen’s wage, partly owing to rapidly increasing job insecurity and the rise of the gig economy, and partly owing to the massive costs associated with administering increasingly complex and unwieldy welfare systems.

Proponents of universal basic income argue that it can be more efficient and more equitable than traditional welfare systems, and will also protect people better as economies change through automation.

“Credible estimates suggest it will be technically possible to automate between a quarter and a third of all current jobs in the western world within 20 years,” Robert Skidelsky, professor of political economy at the University of Warwick, said in a paper last year.

He said a universal basic income that grew in line with productivity “would ensure the benefits of automation were shared by the many, not just the few.”

Economists Howard Reed and Stewart Lansley saw further benefits in a report for Compass last year. As well as a solid income base in an age of increasing economic and social insecurity, a universal basic income would offer “financial independence and freedom of choice for individuals between work and leisure, education and caring, while recognising the huge value of unpaid work,” they said.

Opponents, including the Conservative government which rejected a call from the Scottish National party last year for a basic income scheme, see it as unaffordable and unlikely to incentivise people to find work.

Finland trials basic income for unemployed

The Rich Already Have a UBI

10 percent of all national income is paid out to the 1 percent as capital income. Why not give it to all as a universal basic income?

The universal basic income - a cash payment made to every individual in the country - has been critiqued recently by some commentators. Among other things, these writers dislike the fact that a UBI would deliver individuals income in a way that is divorced from working. Such an income arrangement would, it is argued, lead to meaninglessness, social dysfunction, and resentment.

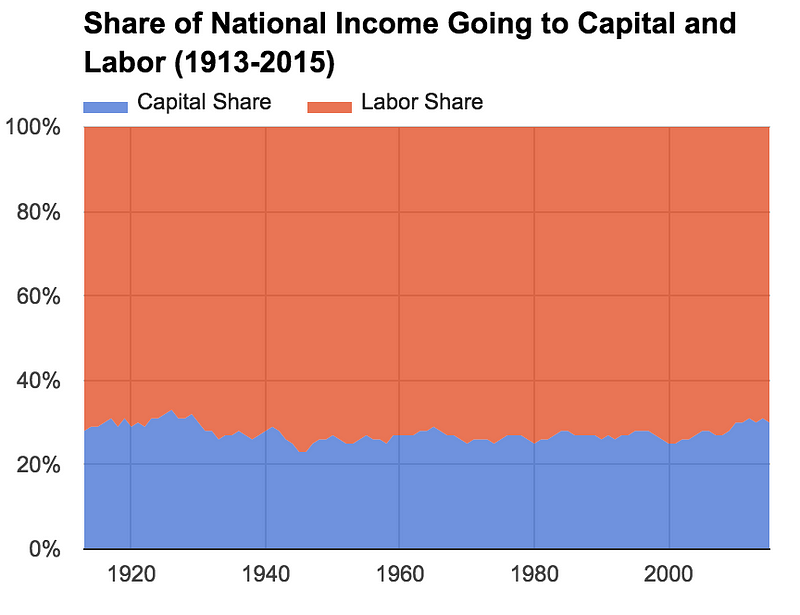

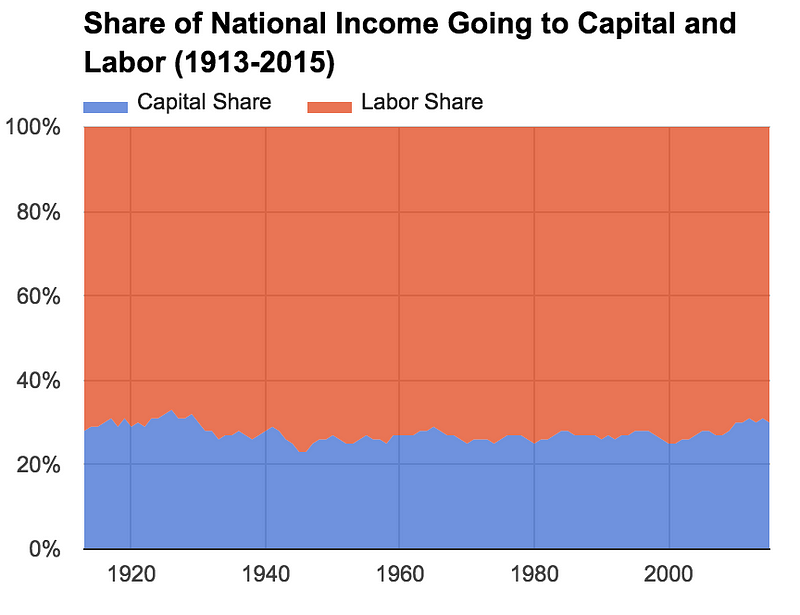

One obvious problem with this analysis is that passive income - income divorced from work - already exists. It is called capital income. It flows out to various individuals in society in the form of interest, rents, and dividends. According to Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (PSZ), around 30 percent of all the income produced in the nation is paid out as capital income.

If passive income is so destructive, then you would think that centuries of dedicating one-third of national income to it would have burned society to the ground by now.

Tithing to the 1 Percent

In 2015, according to PSZ, the richest 1 percent of people in America received 20.2 percent of all the income in the nation. Ten points of that 20.2 percent came from equity income, net interest, housing rents, and the capital component of mixed income. Which is to say, 10 percent of all national income is paid out to the 1 percent as capital income. Let me reiterate: one in ten dollars of income produced in this country is paid out to the richest 1 percent without them having to work for it.

Even if you exclude the capital component of mixed income (since it is connected to work even if the income is not from labor) and housing rents (since these are imputed to homeowners rather than paid to them as cash), that still means that, from equity income and interest alone, the top 1 percent receives 7.5 percent of the national income without having to work for it. Put another way: the average person in the top 1 percent receives a UBI equal to 7.5 times the average income in the country.

If passive income is so destructive, then the income situation of the 1 percent surely is a national emergency! Where does the 1 percent get its meaning with all of that free cash flowing in?

Capital Income for All

The fact is that capitalist societies already dedicate a large portion of their economic outputs to paying out money to people who have not worked for it. The UBI does not invent passive income. It merely doles it out evenly to everyone in society, rather than in very concentrated amounts to the richest people in society.

The idea of capturing the 30 percent of national income that flows passively to capital every year and handing it out to everyone in society in equal chunks has been around since at least Oskar Lange wrote about it in the early parts of the last century. This is, to me, the best way to do a UBI, both practically and ideologically. Don’t tax labor to give money out to UBI “loafers.” Instead, snag society’s capital income, which is already paid out to people without regard to whether they work, and pay it out to everyone.

This might seem like a fantastical idea to some, but this is exactly how the Alaska Permanent Fund and the Permanent Fund Dividend works. Through the Permanent Fund, the state of Alaska owns a lot of capital assets. Those assets deliver annual capital income flows to the state, which are then parceled out in equal amounts to the citizens of Alaska through the Permanent Fund Dividend.

A national UBI would work very similarly. The US federal government would employ various strategies (mandatory share issuances, wealth taxes, counter-cyclical asset purchases, etc.) to build up a big wealth fund that owns capital assets. Those capital assets would deliver returns. And then the returns would be parceled out as a social dividend.

If you have a problem with this, but not the current arrangement where capital income is paid out in huge sums to small fractions of our society, then your issue is not really with passive income. It can’t be.

The Rich Already Have a UBI

Capitalism Is Collapsing -- and the Weird Thing Is That Nothing Is Rising to Replace It

Author Wolfgang Streeck describes the phenomenon as “a death from a thousand cuts."

Some anonymous wise person once observed that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. But Wolfgang Streeck, a 70-year-old German sociologist and director emeritus of the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, thinks capitalism’s end is inevitable and fast approaching. He has no idea what, if anything, will replace it.

This is the premise of his latest book, How Will Capitalism End?, which goes well beyond Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. Piketty thinks capitalism is getting back into the saddle after being ruined in two world wars. Streeck thinks capitalism is its own worst enemy and has effectively cut itself off from all hope of rescue by destroying all its potential rescuers.

“The end of capitalism,” he writes in the introduction, “can then be imagined as a death from a thousand cuts... No effective opposition being left, and no practicable successor model waiting in the wings of history, capitalism’s accumulation of defects, alongside its accumulation of capital, may be seen... as an entirely endogenous dynamic of self-destruction.”

According to Streeck, salvation doesn’t lie in going back to Marx, or social democracy, or any other system, because there is no salvation at all. “What comes after capitalism in its final crisis, now under way, is, I suggest, not socialism or some other defined social order, but a lasting interregnum - no new world system equilibrium... but a prolonged period of social entropy or disorder.”

Five developments, three crises

If we need a historical parallel, the interregnum between the fall of Rome and the rise of feudalism might serve. The slave economy of Rome ended in a chaos of warlords, walled towns and fortress-estates, and enclaves ruled by migrant barbarians. That went on for centuries, with warlords calling themselves “Caesar” and pretending the Empire hadn’t fallen. Streeck sees the interregnum emerging from five developments, each aggravating the others: “stagnation, oligarchic redistribution, the plundering of the public domain, corruption, and global anarchy.”

All these problems and more have grown through “three crises: the global inflation of the 1970s, the explosion of public debt in the 1980s, and rapidly rising private indebtedness in the subsequent decade, resulting in the collapse of financial markets in 2008.” Anyone of a certain age in British Columbia has vivid personal recollections of these crises and the hurt they caused. The strikes and inflation of the 1970s preceded the Socreds’ “restraint” era, and now we mortgage our lives for a foothold in the housing market. Streeck reminds us that it was nothing personal, just business. We weren’t just coping with one damn thing after another; given his perspective, we can see how it all fit together with an awful inevitability.

When the bubble pops

And it continues to fit together. Temporary foreign workers and other immigrants make unions’ jobs harder. “Recovery” amounts to replacing unemployment with underemployment. Education is an expensive holding tank to keep young people off the labour market. Women are encouraged to work so they can be taxed. But middle-class families need two incomes anyway to maintain their status, so they import underpaid immigrant women as nannies. At some point soon these nannies will be sent back to their home countries when Vancouver’s housing bubble pops.

Perhaps the middle-class families will then make their payments by taking in boarders. Streeck’s essays were written over the past few years, and are sometimes a bit dated. For example, he writes that “American oligarchs, unlike their counterparts in other societies like Ukraine or Russia, are of a ‘non-ruling’ type, since they are content to live alongside a public bureaucracy, a state of law, and an elected government run by professional politicians.”

That changed on Nov. 8, when the American oligarchs ousted noncompliant professional politicians and assumed direct power through Donald Trump and his cabinet. (We may yet see an analysis of Trump on Streeck’s blog.) In one essay, Streeck shows how the economic crisis of the 1970s led to the political crisis of today. Postwar Europe and America rebuilt the world by “Fordism” - mass production of durable goods at an affordable price, with few or no options. But Fordism eventually glutted the market with all-too-durable goods. In the 1960s, I wore the hand-me-down nylon socks my father had bought in the 1940s.

In 1972 my wife and I bought a washer and dryer that still run reliably in 2016, without repairs. That couldn’t last, especially as the baby boom tapered off. Capitalism’s solution was to offer customized, short-lived products that didn’t just meet your needs, but met your wants as well. That meant avocado-coloured refrigerators in the 1970s and granite kitchen countertops today, but nothing that really made life easier. It just let consumers express their changing personal tastes and status. And it wasn’t just consumer goods - it was information as well. Streeck notes that public broadcasting systems and a few private networks dominated the media for decades. Now we have hundreds of private channels competing for our attention (and our money).

Public media like the CBC have tried to compete with private radio and TV, with generally awful results: instead of classical music, CBC Radio 2 gives us Mozart’s greatest hits plus Mozart gossip. Radio 1 promotes the careers of inarticulate hip-hop artists and reports commuter woes caused by housing prices and the lack of decent public transit.

Politics as personal fashion statement

What Streeck calls the “individualization of the individual” has afflicted whole nations, including Canada. We no longer vote for a party because our family always has, or because we support most of its policies. We want avocado-coloured day care programs, and granite-counter “world-class” pipeline safety, and if we don’t get both in one party, we stay home and sulk. In effect, we prefer to be consumers of politics as personal fashion statement rather than actually take part in running the country. Marx thought communism would see the withering-away of the state. Instead, capitalism has reduced the state until its chief functions are protecting the rich and policing the poor.

But in the process, capitalism has killed off its rescuers. Who’s going to save the banks in the next collapse? Who’s going to bail out the masters of the financial universe when artificial intelligence takes their jobs? And who’s going to police the poor when taxpayers can’t pay for the cops and the rich are hiring cops for their own gated communities? Wolfgang Streeck sees neither a single cause of capitalism’s collapse nor any obvious successor regime.

The European Union may break up. Climate change may drown south Florida, including Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago. Refugees will keep coming north; they will eventually overwhelm the fences and guards and create new enclaves in Europe and the U.S.A. and Canada.

New pandemics will sweep unchallenged around the world. No coherent political communities will be there to respond to such disasters. Such communities may arise centuries from now, but if Streeck is right, capitalism has ensured that we and our children will never live in them.

Capitalism Is Collapsing -- and the Weird Thing Is That Nothing Is Rising to Replace It

In 2017, Fusing Identity and Class Politics in “Trumpland”

Like millions of other Americans, I was shocked, but perhaps not entirely surprised, by Donald Trump’s victory on election night. His blatant racism and misogyny, cynical exploitation of economic populism, and ties to fascist ideology have generated enormous fears. Yet if we stop at the point of those fears, and let fatalism or blame games drive our response to the Trump regime, then we have already ceded our power to him.

Yes, Trump carries the whiff of fascism, and many of his followers indeed hold racist and misogynist beliefs. But we cannot stop thinking at that point. We should begin to ask ourselves: if we lived in Europe during the rise of fascism in the 1920s or early 1930s, what would we actually do to stop it? In that era many progressives were defending tepid establishment politics, and radicals were making boring speeches, while the fascists were forming chorale groups, hiking societies, and theater troupes to reach and inspire people on an emotional level.

The European left at that time didn’t effectively speak to large numbers of working-class and middle-class citizens, particularly in small towns and cities, and created a vacuum that the far-right was all too eager to fill. In fear of alienating the majority, leftists also failed to defend the rights of Jews, Gypsies, and others who were targeted as the economic scapegoats for the Depression. They failed to have a sense of their own power and their ability to go on the offensive, and went into a reactive mode, defining themselves by what they were against rather than what they were for.

We can see these trends today, as many white progressives propose stepping back from defending so-called “identity politics,” in order to gain more votes from the white, straight majority. Many progressives and radicals likewise seem to be stepping back from class-based “unity politics,” by writing off huge areas of the country’s interior as a backward and hopeless “Trumpland.” Both knee-jerk reactions are enormous, strategic movement-killers at this moment in history.

The ascribed identities of race, ethnicity, and gender, and the achieved status of economic class, have always been inseparable this country’s history. Whether your politics are centered primarily on racial, ethnic, or gender identities, primarily on economic inequalities, or hopefully on both, our common enemy is the white elites from both parties who currently hold power.

“Identity politics” (or particularism) and “unity politics” (or universalism) are not mutually exclusive, and do not have to detract from each other. To clip either wing of our movement is to cripple its ability to fly, and fails to recognize-as Bernie recognized midway through his campaign-that both identity and economic messages can be strengthened at the same time. But in order to do so, we need to recognize our existing strengths, and expand the geographical scope of our social movements into unlikely places.

Our Strengths

First, we should become more confident of the strengths that we have in January 2017, (despite Trump’s Electoral College victory), and compare them to January 2001, when Bush came to power under similar clouded circumstances. Back then, the only recent mass movement that had united different constituencies was the opposition to the World Trade Organization, and the WTO protests in Seattle had only occurred a year before. We weren’t prepared for Bush’s war on civil liberties and Iraq, partly because our capacities were so low.

In contrast to January 2001, we are far more prepared in January 2017. Since then, we’ve had under our belts the antiwar movement, Occupy, climate justice, marriage equality, Black Lives Matter, the Bernie campaign, and Idle No More (expressed most recently at Standing Rock). We weren’t as resilient then against Bush and 9/11 as we are now against Trump and whatever comes next.

We now have far more young people with movement experience, hooked up with each other through social media. Polls show that demographics are in our favor, with younger people far more critical of capitalism and accepting of a diverse society than previous generations. The future looks bright-it’s just the present that sucks. History may view Trump as the last gasp of the racist and misogynist dinosaurs, but only if we view ourselves as the comet that finally wipes them out.

Rural Challenges

Second, the election confirmed our need to confront urban-rural divides in the country like never before. As a geographer, I’d highlight the New York Times map that shows the Democratic vote as a limited “archipelago” along the coasts (with some interior cities and college towns), and the country’s vast interior as a Republican “sea.” It may be easy for urbanites to blame white racial homogeneity, but even some relatively diverse interior areas voted for Trump (in Washington, for example, Republican Yakima County is more diverse than my Democratic city of Olympia). In seeing how we got to this point, let’s examine Wisconsin and Iowa, both states with many rural counties that voted twice for Obama, but went this time for Trump.

Rural Democrats in Wisconsin begged their party leaders in Madison for yard signs, but were told the campaign funds had to be put into TV ads. Hillary Clinton failed to visit Wisconsin even once, and her campaign rebuffed Obama when he volunteered to stump for her in Iowa. The urban-based Party’s arrogant and elitist decisions created a Democratic vacuum in rural areas, isolating its own supporters. The resulting “sea” of Republican yard signs swayed undecided voters with an illusion of their neighbors’ consensus, in counties that actually voted only narrowly for Trump.

Again, asking the question about what could have been done in Europe during the rise of fascism, we have to look to U.S. models that have actually included rural whites in a common cause with marginalized communities. There is perhaps no better example than the Cowboy Indian Alliance, which has so far blocked the Keystone XL Pipeline in the deep-red states of South Dakota and Nebraska. The unlikely alliance combined the treaty rights of Indigenous nations with the populist grievances of their historic enemies: white farmers and ranchers. People power fused identity and economic values, and strengthened Native sovereignty, by defending the land and water from corporate power.

The leader who brought forward the Cowboy Indian Alliance name from earlier groups was Faith Spotted Eagle, an Ihanktonwan Dakota elder who more recently fought the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock. On December 19, Washington Puyallup elector Robert Satiacum gave his vote to Spotted Eagle for president, and to Ojibwe activist Winona LaDuke for vice president. Their names came up in my conversation with Robert a month before, partly because they were Indigenous women leaders fighting oil pipelines, and also because they had built bridges with rural whites. Their most effective approach for cross-cultural organizing has been through social movements, rather than electoral politics, and they will continue the fight under Trump.

As Faith Spotted Eagle said in 2014, “The model of capitalism is trying to suffocate us, because with capitalism you need an underclass. Capitalism cannot survive without poor farmers, without poor Indians, without poor people in the cities who are selling their souls.” When Keystone XL was blocked in 2015, she commented, “We stood united in this struggle, Democrat, Republican, Native, Cowboy, Rancher, landowners, urban warriors, grandmas and grandpas, children, and through this fight against KXL we have come to see each other in a new better, stronger way.”

The Cowboy Indian Alliance was not a fluke, but part of a rich tradition of rural social movement organizing. Community organizers in the South have opposed Klan and police violence, and point out that social programs won by the civil rights movement have also benefited rural whites. Groups such as the Rural Organizing Project in Oregon and Northern Plains Resource Council in Montana are trying to fill the void, but need more funding and resources to compete with far-right politicians and militias for the hearts and minds of rural whites. The success of such alliances fighting for justice and the land weakens the appeal of racist groups fighting against economic scapegoats.

Potential in Small Cities

Third, the election also exposed how our movements have become over-reliant on large urban areas. Progressive/radical movements have long been concentrated in particular urban neighborhoods, and college towns such as Madison, Berkeley, and Olympia. In large cities, movements possess a critical mass to hold large rallies, staff and fund organizations, and create intersectional ties between communities. But if these positive advances do not spread or reverberate in places where movements have fewer people and resources, they will not change the country as a whole, but reinforce the divides in our country.

This is not a criticism of urban-based movements, since historically social change has begun in large cities, but a criticism of keeping social change isolated in “safe” progressive enclaves. On one hand, some white progressives may feel more comfortable in a neighborhood with Co-Exist bumperstickers and Tibetan prayer flags, and activists of color may feel more comfortable in a large city than to support their counterparts in smaller communities. Yet on the other hand, we may come to realize that capitalism needs these enclaves. They keep radicals and progressives cloistered, talking only with each other, and not influencing or learning from other people.

It is a huge mistake for urban progressives and radicals to view rural areas or smaller cities as cultural-political wastelands, and create a vacuum that cedes these areas to the far-right. Just as identity and economic politics are not mutually exclusive, urban and rural organizing can work hand-in-hand. We can use our more open cities and neighborhoods as a base, but also stand in solidarity with movements outside them. For example, Olympia activists recently blockaded a train carrying oil fracking materials to North Dakota, and Minneapolis activists hung a NoDAPL Divest banner at a televised NFL game. We can also understand that the sparks of mass movements sometimes occur in smaller communities, such as Ferguson or Standing Rock, and not assume that urban activists have all the answers.

The greatest potential growth for our movements may not be in either large cities or rural areas. In large cities, residents have generally been exposed to social movements, even if only by seeing headlines or riding past a rally, and have ample opportunities to express their views. On the other hand, residents of small rural towns are often afraid of rocking the boat, and being ostracized by their neighbors, so any movement growth there is bound to be slow and incremental.

But it is in small- and medium-sized cities where the battle for the heart and soul of America is taking place-in cities such as LaCrosse, Wis., Flint, Mich., or York, Pa. There is room for the movement to grow in these “in-between” places, for people to begin to express their views and find limited safety in numbers. But there is not enough support for groups doing the slow, unglamorous work of education and organizing in these smaller cities, where every small rally or leaflet actually counts.

Here in Washington state, for example, the hotspots for the fossil fuel wars have been smaller working-class cities, such as Aberdeen and Hoquiam, where residents have been fighting the proposed Grays Harbor oil terminal. Seattle-based environmental groups are not as successful in mobilizing residents of these former timber towns as local, frontline organizers. Smaller towns and cities such as Forks and Kelso have similarly become frontlines for immigrant rights organizers.

More resources and funds should be directed toward these communities, not only in episodic responses to police shootings or environmental threats, but to steadily build the capacities of local organizers. In Eau Claire, Wis., for example, social movements languished for years after local factories were shut down. But then community members put their energies into starting cooperatives and coffeehouses, working with student groups on the small branch college campus, and building a low-power community radio station. The new artistic venues generated a vibrant music and political scene, and the county stayed blue as the others in western Wisconsin turned red.

Building Hope in Unlikely Places

Our movements need both the depth we develop in large cities through activism among the already-aware residents, and the breadth we develop by diffusing progressive ideas outside the echo chamber, using grassroots education and organizing. By shifting resources to smaller communities, and enlarging our base beyond the progressive enclaves, we need to develop faith in the ability of people to change their views and actions. Urban residents often believe and internalize fixed stereotypes of people from smaller communities as simply “hicks” or “rednecks,” and thereby dismiss these places from the start.

Spanish is better suited than English when describing people and their beliefs. English only has one verb for “to be,” but Spanish verbs differentiate fixed identity from actions. People “are” (ser) a certain type of person, but also “are being” (estar) a certain way. When we hear the racism and misogyny of many Trump voters, we can assume they are (ser) racist, without seeing that the media and educational system have failed to educate them. We can also view them as being (estar) racist against people below them in the social hierarchy, and help redirect their anger against the white elites above them that are the actual source of their problems.

We can begin by switching in our minds from using ser to using estar, to see the possibilities of reaching and organizing unlikely people in unlikely places -particularly if we are from these places. We can try to communicate with our friends, family, and citizens who are attracted to the right-populist message, and offer a left-populist alternative they may not yet have heard in the business-as-usual morass of lies and commercialism.

There is potential hope in everyone, because everyone can change their opinions over time and with events. Social change is all about people changing their minds, and being inspired to act. If we assume their views are permanently fixed, we have already given up on making change. If we assume their views can shift, and they might have something to fight for alongside communities other than their own, we open up more possibilities for hope. In this way, we can enlarge the Rebel Alliance against the Empire.

In 2017, Fusing Identity and Class Politics in “Trumpland”

The Racial Wealth Divide in America Is Staggering-and That's Before Trump Walks into the White House

White households possess roughly 13 times the wealth of their black counterparts.

After predicating his presidential campaign on racist incitement against Muslims, immigrants and Black Lives Matter, President-elect Donald Trump set to work appointing a cabinet that, so far, is setting new records as the wealthiest, and least diverse, in American history. In less than a month, that administration will take the White House of a country that faces the highest levels of wealth disparities along racial lines in nearly three decades.

The Pew Research Center determined in June that white homes possess roughly 13 times the wealth of their black counterparts. Analysis of federal government data also determined that black people in the United States are at least two times as likely as white people to be poor or unemployed. Meanwhile, homes headed by a black person “earn on average little more than half of what the average white households earns,” Pew concluded.

A separate Pew report concluded in 2014 that the wealth gap between white and black people in the United States is at its highest point since 1989.

Those findings were followed by a separate report released in August by the the Institute for Policy Studies and the Corporation for Enterprise Development found that, if economic trends over the past three decades continue on pace, it “will take black families 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth white families have today.” It would take Latino families 84 years to accrue the same wealth as their white counterparts.

The study projects that, by 2014, when people of color are projected to comprise a majority of the U.S. population, the wealth divide with white families on one side and Latino and black families on the other will be double current levels.

“This growing wealth divide is no accident,” states the report. “Rather, it is the natural result of public policies past and present that have either been purposefully or thoughtlessly designed to widen the economic chasm between white households and households of color and between the wealthy and everyone else. In the absence of significant reforms, the racial wealth divide-and overall wealth inequality-are on track to become even wider in the future.”

This economic divide dovetails with racial segregation on the neighborhood level. A report authored by Century Foundation fellow Paul Jargowsky in 2015 found that “more than one in four of the black poor and nearly one in six of the Hispanic poor lives in a neighborhood of extreme poverty, compared to one in thirteen of the white poor.”

"Through exclusionary zoning and outright housing market discrimination, the upper-middle class and affluent could move to the suburbs, and the poor were left behind," he writes. "Public and assisted housing units were often constructed in ways that reinforced existing spatial disparities. Now, with gentrification driving up property values, rents, and taxes in many urban cores, some of the poor are moving out of central cities into decaying inner-ring suburbs."

Impacted communities have long been sounding the alarm about this trend. In their policy platform released earlier this year, the Movement for Black Lives proclaimed, “We demand economic justice for all and a reconstruction of the economy to ensure black communities have collective ownership, not merely access.”

The platform states, “Together, we demand an end to the wars against black people. We demand that the government repair the harms that have been done to black communities in the form of reparations and targeted long-term investments. We also demand a defunding of the systems and institutions that criminalize and cage us.”

The Racial Wealth Divide in America Is Staggering-and That's Before Trump Walks into the White House

This Is the Year Economists Finally Figured Out What Everyone Else Long Understood About 'Free Trade'

The trade deals they shilled for didn’t work out all that well.

This week, Bloomberg’s Noah Smith published a list of “ten excellent economics books and papers” that he read in 2016. Number three on his list was the now celebrated paper, “The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” by economists David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson. Here’s Smith’s summary of the work and its consequences:

This is the paper that shook the world of economics. Looking at local data, Autor et al. found that import competition from China was devastating for American manufacturing workers. People who lost their jobs to the China Shock didn’t find new good jobs-instead, they took big permanent pay cuts or went on welfare. The authors also claim that the China Shock was so big that it reduced overall U.S. employment. This paper has thrown a huge wrench into the free-trade consensus among economists.

Smith’s account of the paper’s effect is absolutely right: Economists’ astonishment and dismay at Autor & Company’s revelations were palpable and widespread. Which raises a question many of us have been raising for years: Why have mainstream economists been the last people to understand the consequences of the policies they advocate? During the debate that swirled around the congressional legislation granting permanent normal trade relations to China in 1999 and 2000, unions, progressive think tanks (most especially the Economic Policy Institute), and other liberal groups predicted with unerring accuracy the job loss that would follow if PNTR was enacted, the concomitant failure to generate adequate replacement jobs, and in a few cases, even the political shifts likely to follow in the states of the rapidly deindustrializing Midwest-shifts that did not fully manifest themselves until this November. But to the high priests of mainstream economics, and to the Robert Rubins and Timothy Geithners who provided policy guidance to the Bill Clinton and Barack Obama administrations, these were fringe opinions, narrowly self-interested, and not worthy of serious consideration.

Well, yes-the industrial Midwest was self-interested; its residents had an understandable reluctance to seeing their economies dismantled and their middle-class decimated.

The lesson from all this is that mainstream economics has to be viewed less as an empirical, much less scientific, discipline, and more as an elegant regurgitation of the worldview of dominant financial powers. By endorsing the efficiency of markets and the concomitant curtailment of regulation, by assuming that trade with industrializing, poverty-wage mega-nations would not have a devastating impact on American manufacturing workers, by a thousand other deaths of common sense, the American economic mainstream reduced itself to little more than a priesthood serving the gods of Wall Street. The dissents of dissident economists-from Joe Stiglitz and Dani Rodrik to Dean Baker, Jared Bernstein, and the gang at EPI and Global Trade Watch, from Thea Lee at the AFL-CIO to Mark Levinson at the clothing and textile workers unions and Clyde Prestowitz at his own institute, from the pages of The American Prospect to the pages of, well, The American Prospect-were drowned in propaganda masquerading as economics.

Now that the jobs have fled, now that the deregulation has led to an epochal collapse and a woefully selective recovery, the masquerade is over-or rather, should be over. The whole point of Trickle Downers is to hasten it to its long overdue end.

This Is the Year Economists Finally Figured Out What Everyone Else Long Understood About 'Free Trade'

iPhone manufacturer Foxconn plans to replace almost every human worker with robots

China’s iPhone factories are being automated

Foxconn, the Taiwanese manufacturing giant behind Apple’s iPhone and numerous other major electronics devices, aims to automate away a vast majority of its human employees, according to a report from DigiTimes. Dai Jia-peng, the general manager of Foxconn’s automation committee, says the company has a three-phase plan in place to automate its Chinese factories using software and in-house robotics units, known as Foxbots.

The first phase of Foxconn’s automation plans involve replacing the work that is either dangerous or involves repetitious labor humans are unwilling to do. The second phase involves improving efficiency by streamlining production lines to reduce the number of excess robots in use. The third and final phase involves automating entire factories, “with only a minimal number of workers assigned for production, logistics, testing, and inspection processes,” according to Jia-peng.

The slow and steady march of manufacturing automation has been in place at Foxconn for years. The company said last year that it had set a benchmark of 30 percent automation at its Chinese factories by 2020. The company can now produce around 10,000 Foxbots a year, Jia-peng says, all of which can be used to replace human labor. In March, Foxconn said it had automated away 60,000 jobs at one of its factories.

In the long term, robots are cheaper than human labor. However, the initial investment can be costly. It’s also difficult, expensive, and time consuming to program robots to perform multiple tasks, or to reprogram a robot to perform tasks outside its original function. That is why, in labor markets like China, human workers have thus far been cheaper than robots. To stay competitive though, Foxconn understands it will have to transition to automation.

Complicating the matter is the Chinese government, which has incentivized human employment in the country. In areas like Chengdu, Shenzhen, and Zhengzhou, local governments have doled out billions of dollars in bonuses, energy contracts, and public infrastructure to Foxconn to allow the company to expand. As of last year, Foxconn employed as many as 1.2 million people, making it one of the largest employers in the world. More than 1 million of those workers reside in China, often at elaborate, city-like campuses that house and feed employees.

In an in-depth report published yesterday, The New York Times detailed these government incentivizes for Foxconn’s Zhengzhou factory, its largest and most capable plant that produces 500,000 iPhones a day and is known locally as “iPhone City.” According to Foxconn’s Jia-peng, the Zhengzhou factory has some production lines already at the second automation phase and on track to become fully automated in a few years’ time. So it may not be long before one of China’s largest employers will be forced to grapple with its automation ambitions and the benefits it receives to transform rural parts of the country into industrial powerhouses.

There is, however, a central side effect to automation that would specifically benefit a company like Foxconn. The manufacturer has been plagued by its sometimes abysmal worker conditions and a high rate of employee suicide. So much so in fact that Foxconn had to install suicide netting at factories throughout China and take measures to protect itself against employee litigation. By replacing humans with robots, Foxconn would relieve itself of any issues stemming from its treatment of workers without having to actually improve living and working conditions or increase wages. But in doing so, it will ultimately end up putting hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people out of work.

iPhone manufacturer Foxconn plans to replace almost every human worker with robots

Finland trials basic income for unemployed

Government hopes two-year social experiment will cut red tape, reduce poverty and boost employment

Finland has become the first country in Europe to pay its unemployed citizens an unconditional monthly sum, in a social experiment that will be watched around the world amid gathering interest in the idea of a universal basic income.

Under the two-year, nationwide pilot scheme, which began on 1 January, 2,000 unemployed Finns aged 25 to 58 will receive a guaranteed sum of €560 (£475). The income will replace their existing social benefits and will be paid even if they find work.

Kela, Finland’s social security body, said the trial aimed to cut red tape, poverty and above all unemployment, which stands in the Nordic country at 8.1%. The present system can discourage jobless people from working since even low earnings trigger a big cut in benefits.

“For someone receiving a basic income, there are no repercussions if they work a few days or a couple of weeks,” said Marjukka Turunen, of Kela’s legal affairs unit. “Working and self-employment are worthwhile no matter what.”

The government-backed scheme, which Kela hopes to expand in 2018, is the first national trial of an idea that has been circulating among economists and politicians ever since Thomas Paine proposed a basic capital grant for individuals in 1797.

Attractive to the left because of its promise to lower poverty and to the right - including, in Finland, the populist Finns party, part of the ruling centre-right coalition - as a route to a leaner, less bureaucratic welfare system, the concept is steadily gaining traction as automation threatens jobs.

A survey last year by Dalia Research found that 68% of people across all 28 EU member states would “definitely or probably” vote in favour of some form of universal basic income, also known as a citizens’ wage, granted to everyone with no means test or requirement to work.

In a referendum last year 75% of Swiss voters rejected a basic income scheme, but that proposal - to give every adult an unconditional minimum monthly income of SFr2,500 (£1,980) - would have meant increasing welfare spending from 19.4% to around a third of the country’s GDP, and did not have government backing.

Basic income experiments are also due to take place this year in several cities in the Netherlands, including Utrecht, Tilburg, Nijmegen, Wageningen and Groningen. In Utrecht’s version, called Know What Works, several test groups will get a basic monthly income of €970 under slightly different conditions.

One will get the sum as unemployment benefit, with an obligation to seek work - and sanctions - attached. Another will get it unconditionally, whether or not they seek work. A third will get an extra €125 providing they volunteer for community service. Another will get the extra €125 automatically, but must give it back if they do not volunteer.

The Italian city of Livorno began giving a guaranteed basic income of just over €500 a month to the city’s 100 poorest families last June, and expanded the scheme to take in a further 100 families on 1 January. Ragusa and Naples are considering similar trials.

In Canada, Ontario is set to launch a C$25m (£15m) basic income pilot project this spring. In Scotland, local councils in Fife and Glasgow are looking into trial schemes that could launch in 2017, which would make them the first parts of the UK to experiment with universal basic income.

The Green party in the UK has supported the idea of a citizen’s wage, partly owing to rapidly increasing job insecurity and the rise of the gig economy, and partly owing to the massive costs associated with administering increasingly complex and unwieldy welfare systems.

Proponents of universal basic income argue that it can be more efficient and more equitable than traditional welfare systems, and will also protect people better as economies change through automation.

“Credible estimates suggest it will be technically possible to automate between a quarter and a third of all current jobs in the western world within 20 years,” Robert Skidelsky, professor of political economy at the University of Warwick, said in a paper last year.

He said a universal basic income that grew in line with productivity “would ensure the benefits of automation were shared by the many, not just the few.”

Economists Howard Reed and Stewart Lansley saw further benefits in a report for Compass last year. As well as a solid income base in an age of increasing economic and social insecurity, a universal basic income would offer “financial independence and freedom of choice for individuals between work and leisure, education and caring, while recognising the huge value of unpaid work,” they said.

Opponents, including the Conservative government which rejected a call from the Scottish National party last year for a basic income scheme, see it as unaffordable and unlikely to incentivise people to find work.

Finland trials basic income for unemployed

The Rich Already Have a UBI

10 percent of all national income is paid out to the 1 percent as capital income. Why not give it to all as a universal basic income?

The universal basic income - a cash payment made to every individual in the country - has been critiqued recently by some commentators. Among other things, these writers dislike the fact that a UBI would deliver individuals income in a way that is divorced from working. Such an income arrangement would, it is argued, lead to meaninglessness, social dysfunction, and resentment.

One obvious problem with this analysis is that passive income - income divorced from work - already exists. It is called capital income. It flows out to various individuals in society in the form of interest, rents, and dividends. According to Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (PSZ), around 30 percent of all the income produced in the nation is paid out as capital income.

If passive income is so destructive, then you would think that centuries of dedicating one-third of national income to it would have burned society to the ground by now.

Tithing to the 1 Percent

In 2015, according to PSZ, the richest 1 percent of people in America received 20.2 percent of all the income in the nation. Ten points of that 20.2 percent came from equity income, net interest, housing rents, and the capital component of mixed income. Which is to say, 10 percent of all national income is paid out to the 1 percent as capital income. Let me reiterate: one in ten dollars of income produced in this country is paid out to the richest 1 percent without them having to work for it.

Even if you exclude the capital component of mixed income (since it is connected to work even if the income is not from labor) and housing rents (since these are imputed to homeowners rather than paid to them as cash), that still means that, from equity income and interest alone, the top 1 percent receives 7.5 percent of the national income without having to work for it. Put another way: the average person in the top 1 percent receives a UBI equal to 7.5 times the average income in the country.

If passive income is so destructive, then the income situation of the 1 percent surely is a national emergency! Where does the 1 percent get its meaning with all of that free cash flowing in?

Capital Income for All

The fact is that capitalist societies already dedicate a large portion of their economic outputs to paying out money to people who have not worked for it. The UBI does not invent passive income. It merely doles it out evenly to everyone in society, rather than in very concentrated amounts to the richest people in society.

The idea of capturing the 30 percent of national income that flows passively to capital every year and handing it out to everyone in society in equal chunks has been around since at least Oskar Lange wrote about it in the early parts of the last century. This is, to me, the best way to do a UBI, both practically and ideologically. Don’t tax labor to give money out to UBI “loafers.” Instead, snag society’s capital income, which is already paid out to people without regard to whether they work, and pay it out to everyone.

This might seem like a fantastical idea to some, but this is exactly how the Alaska Permanent Fund and the Permanent Fund Dividend works. Through the Permanent Fund, the state of Alaska owns a lot of capital assets. Those assets deliver annual capital income flows to the state, which are then parceled out in equal amounts to the citizens of Alaska through the Permanent Fund Dividend.