"Probably he had them to use as company, as he was childless"

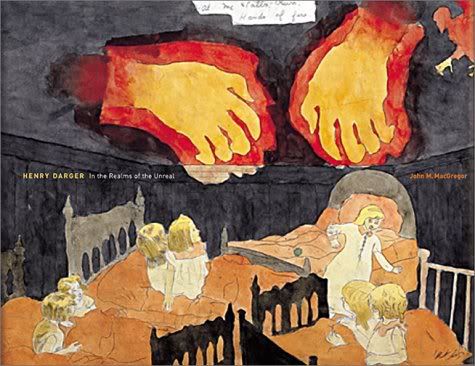

Shortly before his death in 1973, the landlords of janitor/recluse Henry Darger discovered in his room a 15,143 page manuscript entitled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion and hundreds of accompanying illustrations, some of them over 9 feet long and presented on both sides of lengths of butcher paper.

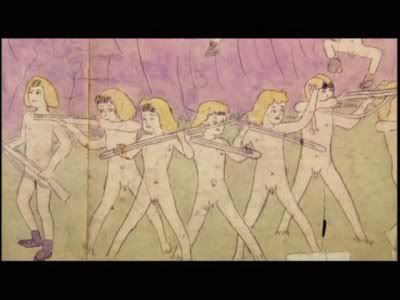

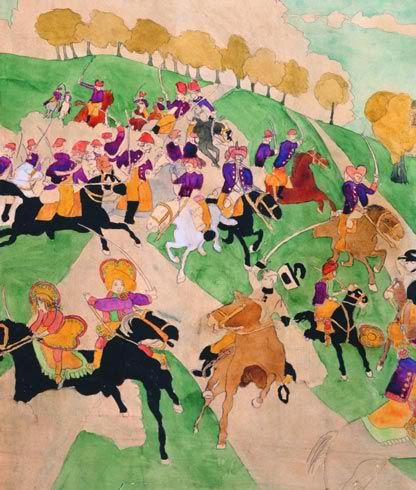

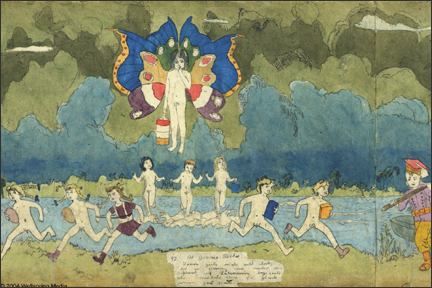

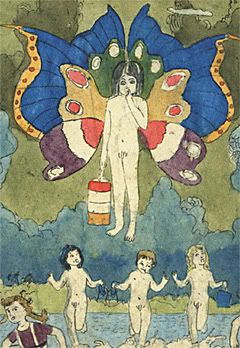

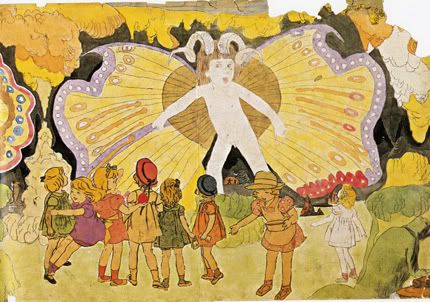

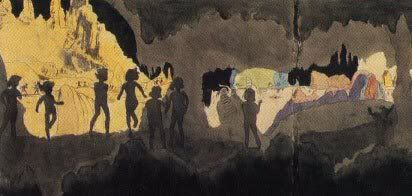

Darger's writing and artwork a like demonstrate both his lack of formal schooling in either and an ability to synthesize the techniques and styles (and materials) that inspired him. The manuscript tells the story of the Vivian girls, nearly superhuman sisters (Darger contested that girls are just as brave, if not moreso, than boys) who lead the aforementioned rebellion agains the Glandelineans. They are aided by the Christian soldiers of Abbiennia and by horned, winged creatures called Blengins.

Darger's story seems to have been all-consuming. He spoke very little, ignored the children who lived in his building despite his constant efforts to adopt, and could not afford even to keep a dog. He spoke to himself in different voices, presumably in the characters of the fantasy he was illustrating. He went to Mass daily and took communion, and wrote extensively about his struggle with religion and temper. Raised by a single, ailing father, Darger had been sent while still very young to a home for imbeciles, escaping from a work farm when he was 16 to return to Chicago, where he'd been born. He worked into his 70's as a janitor, among other menial jobs, at a Catholic hospital. And he wrote, and drew, and at times kept detailed account of the weather.

His writing drew from Civil War histories, war films, the Oz books, and other childhood favorites. The drawins utilized material from the magazines, newspapers, and coloring books Darger collected. Many of his figures are traced versions of ads or cartoon characters. He learned that he could get these images reproduced and enlarged (for what was certainly a hefty price in the 1940's) and thereby reuse them. The paintings themselves do not conform to any one technique or style, but combine collage, tracing, appropriating images (like dresses, or faces) for inanimate objects like flowers, and his own drawings.

What I find fascinating about Darger is not only the imaginative way he constructed his drawings, which have a bizarre children's-book-gone-wrong quality, but the fact that he did it without any outside input. He appropriated images, of course, but the paintings themselves, the style, technique, is wholly his own. I love that it was created in the vaccum of his imagination. That he had no idea "what he was doing," and did it anyway.

Obviously Darger had a difficult life, and something was not quite right. But he left behind something amazing and articulate and original.

The reason I'm thinking about him, and making this far too elaborate post, is that the Frye in Seattle is currently showing a collection of Darger paintings. They're going back into storage after this, so if you're in the area, now's your chance. The long, double-sided paintings are housed in glass cases in the middle of the room, so you can see both sides. You walk around them, rather like a maze. They're so full of figures and colors and bits of narrative that it's overwhelming. But it's free, so I'll be back.

Darger's obsession with a made-up world wasn't interesting only from the point of view of the art critic or the psychologist. As I walked through his creation, I thought about how like his fixation was to feelings I recognize in myself, though nowhere near to that degree. I recall childhood stories and games and fake maps. I recall a role-playing story (based on the world of The Phantom of the Opera but soon veering off into original territory) that continued after members of it went offline, through letters and photos and packages. I have letters written in character from friends to characters of mine; love poems, drawings, reports of home life. We appropriated images and storylines and names from favorite texts. An R.L. Stevenson character here, a photo of a Dark Shadows cast member there. What we created made little sense to the outside, and was an amalgamation of other peoples' creations. But then, it didn't go on for fifty years. I'm reminded of JRR Tolkien's more sociable obsession with words and maps and histories. Or the Bronte sisters' fictitious adventures before their publishing days. Is this what happens when that impulse finds no other outlet? Or when it is not countered by the expectations of society that one should grow up, put away Oz, and create something "original"?

The more I look at these drawings and paintings, the more I love them. The more they speak to me, as a matter of fact. Darger may have lived in his own little world, and we may never know just what made him create this obsessive amount of material. But it's not the ravings of someone incomprehensible to the rest of humanity, and maybe that's why he's so disturbingly fascinating. It's possible to insert yourself into his world a little, once you know what you're looking at, and maybe that's scary. I just find it fascinating. I'm sharing these particular images because they were the largest and had the best resolution when I did a simple search. For more information, rent In the Realms of the Unreal, a flawed documentary that is still the best introduction I know of.

I'll leave you with a few more images. Apologies to the person on my flist who let me know this was coming to Seattle--I have a feeling it was

stefanie_bean but I can't remember.