THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 7 - Style in icons (р. 2)

...This unconditional enthusiasm for the “old” style is characteristic of individuals or groups (through ignorance or out of totally "earthly" interests), but the Church has never made any decision concerning style, prescribing one or proscribing another. The canonicity of and the admissibility of a particular style are evaluated by the Church on a case-by-case basis, without any pre-established rule, by direct examination of particular icons. And if, when it comes to the iconographic canon, the number of historical precedents is limited for each subject, in the field of style no specific limit can be established. For this reason alone, an icon that has slipped from the Greek style to the Latin style or one that has been painted in a purely Academic style may not be excluded from the ranks of icons. Similarly, the "Byzantine" style does not automatically make holy an image, any more today than in past centuries.

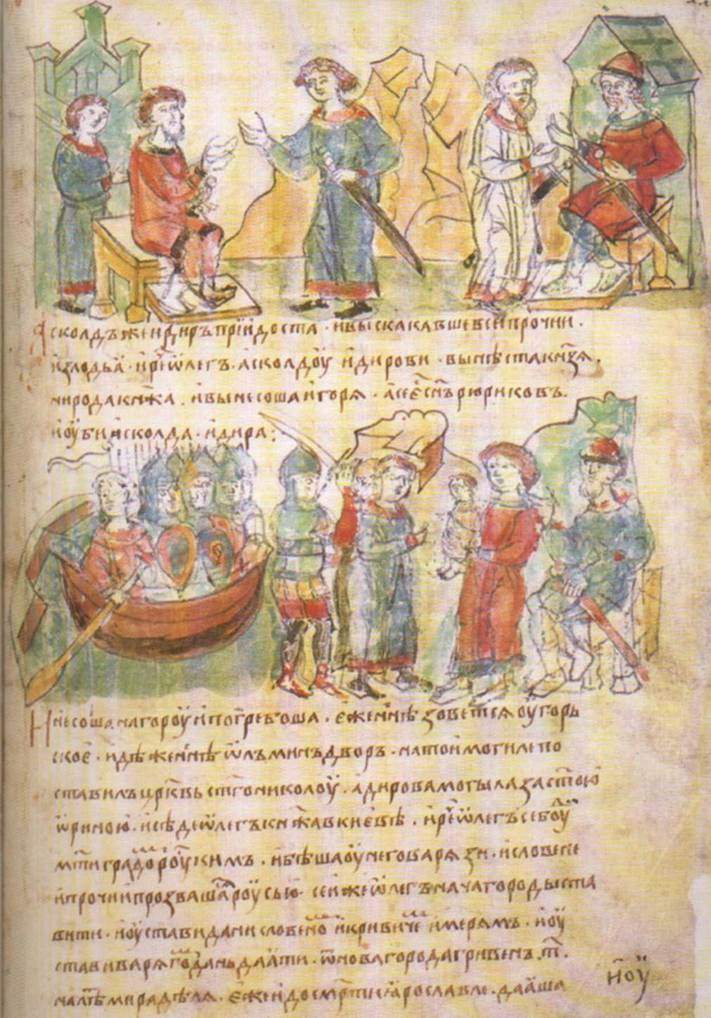

Let us add here, in passing, an observation that the theologians of the icon of the first Russian emigration have lost sight of. Those who know, even superficially, the history of the art of the Christian countries know that the so-called "Byzantine" style was used not only for sacred images, being the only style in existence at its time. Icon painting was indeed, for many centuries, the main sphere of artistic activity, but not the only one. Sometimes the same artists, icon painters or churches decorators, illuminated historical chronicles and scientific treatises. None of them shifted for this to a specifically secular style. In the illuminated chronicles we find battle scenes, city views, tableaux of everyday life including feasts and dances, or figures representing Gentile peoples, all treated in the same style as the sacred images of the same period, presenting the same features to which today's "theologians of the icon" attribute spiritual value and an evangelical worldview.

убийство Аскольда и Дира.

Радзивилловская летопись, 15 в.

Там же.

Убийство варягов-христиан.

Лицевой летописный свод

1540-е - 1560-е гг.

Битва на куликовом поле.

Миниатюра рукописи 17 в. "Сказание о Мамаевом побоище".

In these images we find "reverse perspective" (or rather a collection of different types of projection that give objects clearly legible contours and characteristics). There too is the famous "absence of shadow" (it would be more correct to speak of the reduction of shadows to thin, highly accentuated lines). Presented on the same plane are events very distant in time and space. There too we find what the "theologians" call dispassion: this impassivity of the figures as if petrified, unnatural gestures, the calm and expressionless rendering of faces turned towards the viewer, front-on or in three-quarter profile. Why this impassivity of the faces warriors in combat? And of jugglers busy juggling? Not to mention the "impassive" torturers or murderers whose images we find in the chronicles. For the simple reason that the medieval artist did not yet know how to represent the expression of emotions on faces. He was incapable or doing so, nor was he particularly concerned to do so. In the Middle Ages, it is what is typical, permanent, and general that is described. But what is transient, which sets apart, and individualizes, was considered of little interest. Neither passing emotions nor subtle psychological nuances had their place in literature or in music or in painting, whether secular or sacred.

Our opponents will argue perhaps that the medieval chronicles were a noble genre, being composed and illustrated by monks, and that there is nothing surprising in the transposition of this sacred style into these texts. So let us step down one more level and remind ourselves of what is obvious to any art lover: a great historical style is never exclusively either the bearer of spirituality or profane. It is used in both in elevated subjects and in popular ones.

Let us therefore look at Russian popular images, produced by both monastic and lay workshops, and widely disseminated from the seventeenth century onwards, although existing long before, first as colored hand drawings, then as colored woodblock prints and finally as copper engravings. The artistic competence of their authors, both general and artistic, varied considerably. These images were marketed throughout Russia, in city and countryside, among rich and poor, among intellectuals as much as among simple folk, whether pious or not very religious. Some of these purchased icon subjects, edifying stories, views of monasteries or portraits of archbishops, while others preferred portraits of generals, battle scenes, depictions of parades or festivals, historical images or views of distant cities. Others chose song lyrics or popular illustrated stories, jokes and anecdotes, even the most scabrous.

In the famous facsimile collection[1] of these popular images by Dimitri Rovinsky, there is a full volume of these images. Stylistically, this volume, intended only for adults, is absolutely similar to others that bring together "neutral" or sacred images. The difference lies in the subjects: Khersonia, a mesmerizing woman of easy virtue, ready to provide the services expected by these gentlemen; a soldier, a girl on her knees, at the start of proceedings; an idle youth pinching the cook's buttocks. But no trace here of this terrible zhivopodobiye (resemblance to the living) of the Academic style. Pure “Byzantine”: the perspective is "reversed", shadows are absent, colors are built from local tones, space is flat and random. Projections and perspectives are mixed to suit the subject matter. The characters pose for the viewer, almost always direct on, rarely in three-quarters and almost never in full profile. Their feet barely touch the ground, their hands are frozen in theatrical gestures. Their clothes fall in rigid folds, sometimes covered with "flattened" ornaments. Finally, their faces are not only very similar, but are completely identical to the faces of the saints of another volume of the same collection. There is the same perfect, graceful oval, the same clear and calm eyes, the same archaic smile etched on with the same stroke of the burin: the artist being simply unable to render differently a depraved man and an ascetic, a female saint and a whore.

[1] Dimitri Rovinsky, Руские народные картинки, Saint-Pétersbourg, 1881.

What a pity E. Trubetskoy, L. Uspensky and all those who so widely diffuse their wisdom are three centuries behind the times: they could have explained to the artists for which images Academic zhivopodobiye was best, and shown those for which the Byzantine style was the only one possible. But too late: the masters of popular imagery, without taking their leave, have applied the single "spiritualized style" everywhere. And they have forgotten nothing, these wretches! Even inscriptions are present in their depraved images! Mr. Trik, Khersonia, Paramochka we read in large Slavonic letters next to these very far-from-holy characters. Explanatory inscriptions are also part of the compositions: we will avoid quote these popular, witty verses of scant propriety. There is room also for the symbolic, this for-the-initiated only sign language: the impassive face of a lady shown to the viewer in a very impassioned attitude displays an assortment of beauty spots which, according to location, can signify a passionate call to share the pleasures of love, contemptuous refusal, or the pain of separation. There is equally a fairly well-developed symbolic color code. The hardly theological explanations of red and black, yellow and purple relate to the needs of the ladies of easy virtue and men seeking amatory prey. There are also symbols whose erotic meanings are so simple and direct as to need no explanation: an huge red "flower" with a black heart on the front of the skirt of a woman of easy virtue, or a saucer with two hen’s "eggs" alongside a young man preparing to fight. [1]

[1] In Russian (as also in German) there is a play on words here, “eggs” being a popular term for testicles.

Встречаются и символы попроще, понятные без объяснений в своей прямолинейной образности - например, огромный красный цветок с чёрной серединкой на юбке доступной девицы или блюдечко с парой куриных яиц у ног удалого молодца, приготовляющегося к кулачному бою...

It remains to add that in Western Europe too, there also existed, in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance as in modern times, profane images done in the "sacred" style. Obviously there again nobody bothered to explain to the artists what style was profane and what style was sacred.

As we can see, it is not so easy to distinguish the stylistic features that make the icon an icon and that distinguish sacred images from profane and even unseemly ones. If we want to build a "theology of the icon" on the basis of stylistic analysis, it is vital that we know at least the basics of the theory of Fine Arts, otherwise not only will we make ourselves ridiculous in the eyes specialists with outlandish conclusions, but we will also risk falling into heresy, because the icon is not only a work of art. All the lies peddled about the icon at the scientific level also affect the spiritual realm.

Let us be clear: any sacralization of the "Byzantine" style, or any other great historical style, is a pure invention, a falsification. Stylistic distinctions are for art historians, not theologians. The Church ignores styles, or rather it accepts them indiscriminately because any major historical style is like a stage in its life, it is the expression of its mind at a particular point in time, which can never be "fallen" or profane, even if it goes through periods of strength and weakness. Only the mind of an individual artist can be fallen.

Свт. Николай Мирликийский

Т. А. Нефф.

Мозаичная икона из Исаакиевского собора санкт-Петербурга. 1850-е гг.

Свт. Николай Мирликийский

Невьянск, начало 19 в.

This is why the Church retains the habit of subjecting each new icon to the judgment of the hierarchy. A priest or bishop recognizes and blesses an icon, or, as the guardian of the spirit of authenticity, rejects it as unworthy.

What are his criteria when so doing? What does this representative of the hierarcy examine, what does he check, in this work submitted to him? Does he assess the level of the artist's theological education? The iconographic canon exists precisely so that artists can, without getting lost in theological meanders, devote themselves entirely to their sacred profession, knowing that all the dogmatic work on the subjects of icons has been done for them. To judge the canonicity of the icon on this level it is not necessary to be a member of the hierarchy, nor even a Christian. Any specialist, of whatever religious affiliation, can judge the correspondence of the icon to Christian dogma, precisely because iconographic schemes exist to express this dogma and make it intelligible.

So, is it the style of the icon that is judged and evaluated by the hierarchy? We have already, based on a broad range of historical material, that this opposition between the "Byzantine and not resembling Nature" and "Academic and resembling nature", is a twentieth century invention that has never existed in the eyes of the Church. The fact that some members of the hierarchy accept only the first of these styles proves nothing, since there are a lot of senior people in the Church who accept only the second, finding the first to be vulgar, "dead and buried" and primitive. It is all a matter of the taste, habits and the cultural level of the interested parties, and has nothing to do with their correct or warped theology or state of mind. In fact the question of style in fact resolves itself automatically, by market forces or by the system of commissioning (if you commission an icon you choose an artist whose stylistic orientation you know, generally reflecting your own preferences, you select a model, etc.). We venture to express the opinion that the free competition between styles, which exists today in Russia, is very beneficial for the icon because it pushes the two schools to promote quality in the first place, to reveal their true artistic value, and to be convincing not only for their supporters, but also for the opponents of their respective styles. In this way the proximity of the "Byzantine" school forces the Academic school to be more severe, more sober, more expressive. And "Byzantine" school, living cheek-by-jowl with the Academic school, avoids degenerating into and being satisfied with second-rate craftsmanship.

So what is this element accepted or rejected by the hierarchy, to whose judgment the sacred images are subjected, since the questions of iconography have been resolved in advance and those of style are exterior to the Church? Which criterion have we failed to mention? Why, despite all the free rein the Church gives to iconography, does it not accept every image purporting to be an icon? It is this criterion, the most important of all, that we address in the next chapter of this book.