Yesterday, in history

I meant to post his yesterday, but I ran out of time.

In the early morning fog of 29 May 1914, the ocean liner RMS Empress of Ireland was steaming down the St. Lawrence on its return trip to England, just offshore Rimouski, Quebec, when it collided with the Norwegian collier SS Storstad, or more precisely, when the Storstad collided with her (though there is evidence to suggest both Captains made errors of judgement). Both Captains should have known to maintain their headings due to the dense fog - both, it seems did not. Of the 1,477 persons on board the ship, 1,012 died, making this the largest of any Canadian maritime accident in peacetime, and second only to the the sinking of the Titanic at the time - though now something largely forgotten by most Canadians. The Storstad did not sink.

The immense lost of life was not a failure to provide lifeboats or a design failure like the Titanic, but a combination of where she was struck, a failure to close watertight doors and the fact that so many pothole windows were left open to try and air out staterooms, despite maritime regulations requiring them to be shut once the vessel left port. The ship went down rapidly.

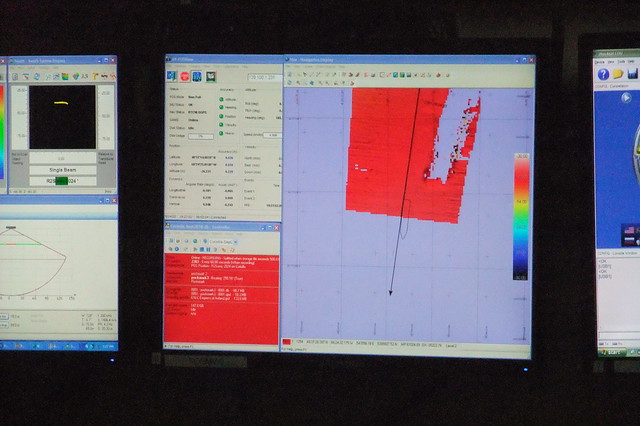

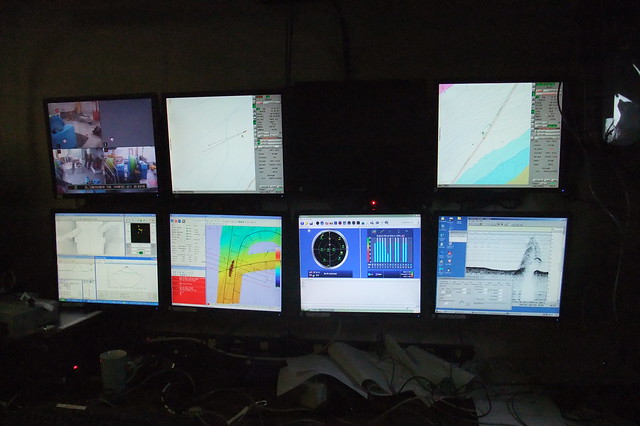

While doing fieldwork sailing to and from Rimouski in 2010, we allowed another research group some shiptime to test their multibeam bathymetric system. The RMS Empress of Ireland make a logical target in just 40 m of water. Seeing the undisturbed wreck apear on the screens in the lab was really a fascinating experience.

On the surface, there was nothing to see but river and fog, and the one buoy to warn of a shallow obstruction. Below, clear as day on all our screens were bright reflections on the depth sounder and multibeam screens, indicating hard surfaces. It was so unusual to see straight lines, and in fact, the clear outline of a ship, despite the near century of sediment build up, decay, and any incursion of life. Most of what we see has the organic, smooth lines of naturally formed and eroded geology. Even when we do see human-made objects (like our own equipment), it's never so large that you can read its very shape. It was haunting to see the clear outline of the Empress, silently lying on the seabed.

The St. Lawrence is deceptive. In French, we have the word Fleuve to better describe this mighty river which drains into the sea. We do say 'seaway' in English... but river is insufficient. While sometimes calm, the waters are brakish, the tides surprisingly large and the currents stronger than you would imagine for a protected river. I certainly made sure my porthole window was shut. But, a cruise liner is filled with passengers with little to no experience of being at sea. In the dense fog as we surveyed, it was easy to imagine the chaos, especially in the early morning dark. Many passengers may not even have awoken. The story of the sinking, and subsequent inquiry makes for some dramatic and in fact scandalous reading.

The crew of our vessel viewed the ship somewhat solemnly, not so much because they felt the connection to events of a century previous, but because more recently, the wreck itself had claimed more lives. In only 40 m of water, skilled scuba divers can explore it. But in cold water with low visibility, it is a dangerous dive. In 2009, the year before our survey, six divers had died.