"Why so little socially progressive speculative fiction?"

…because I’m working on a question someone posed during Karen Joy Fowler's talk last week on feminism in SF and the James Tiptree, Jr. Literary Award. The question was why does the supposed literature of change appear - at least from the outside - to be conservative or non-imaginative in its projections of the future, especially in terms of gender, class, and so forth compared to the literary mainstream.

That’s a fair and interesting question. I mean, if you’re aware of the Sad and Rabid Puppies and what they’ve been trying to do to science fiction, particularly the Hugo Award, and not an avid reader or scholar of SF, you’re unlikely to know the best that the field has to offer is much more diverse and socially progressive than what you typically see in movie theaters or on best-seller shelves.

But I also think it’s a flawed premise, because you can’t pick the best of any other genre (say, the college-literary-journal genre) and compare that to the worst of another (in this case, SF).

The first part of my answer to the question is, if science fiction is, as Sir Arthur C. Clarke repeatedly said, “the only realistic fiction,” that’s in part because of his love for what SF can do, and in part because its practitioners are held to a (often ridiculously) high level of realism, necessary for maintaining the reader’s willing suspension of disbelief - while at the same time developing alien or future or worlds otherwise utterly different from our own. I mean, I’m working on a story right now where the editor’s only revision request revolves around working out the punishingly challenging math of some new physics I’ve proposed (for Analog SF magazine, naturally). Why? Because we can’t have the highly educated audience being distracted from the main drive of my story (how poisonous traditions and sense of communal honor combined with conflict can lead to tragedy) by faults in the reality of this future alien world-building.

It’s a real challenge to create, for example, an anarchist utopia populated by humans that’s believable (though I was deeply influenced by Le Guin's The Dispossessed). But it’s easy to write yet another dystopian future, because so much of human history provides examples of the horrors humans bring upon the world. It’s not difficult to imagine a future with increasing power differentials between rich and poor, and the power of our technologies suggests that the world is more likely to look like a gritty cyberpunk vision than a Kim Stanley Robinson future.

One of the drivers of my series of Jupiter stories (which will accumulate into an eventual novel) is that I wanted to experiment with how we as a species could evolve human civilization beyond capitalism (at least as practiced today in our culture) to an egalitarian, socialist society - and to transition in a natural and realistic way, co-existing within a broader capitalist society.

The best answer to this question is to refer the questioner to Sturgeon’s Law. Theodore Sturgeon (known for his urging everyone to “Ask the next question” - his signature included a stylized Q with an arrow through it; more here if you’d like to see his essay on this) had grown weary of defending speculative fiction for so many years and pointed out that SF was the only genre evaluated by its worst examples rather than its best.

“When people talk about the mystery novel,” he said at the World Science Fiction Convention in Philadelphia in 1953, “they mention The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. When they talk about the western, they say there’s The Way West and Shane. But when they talk about science fiction, they call it ‘that Buck Rogers stuff,’ and they say ‘ninety percent of science fiction is crud.’

“Well, they’re right. Ninety percent of science fiction is crud. But then ninety percent of everything is crud, and it’s the ten percent that isn’t crud that is important. And the ten percent of science fiction that isn’t crud is as good as or better than anything being written anywhere.”

SF authors are and have been for a long time addressing progressive social concerns right now. I could point to some of the biggest contemporary names, such as Margaret Atwood, Paolo Bacigalupi, Elizabeth Bear, Cory Doctorow, Ann Leckie, Ian McDonald, Seanen McGuire, Linda Nagata, Nnedi Okorafor, Kim Stanley Robinson, and a thousand others who might not be published through major presses but which, nonetheless, have a major impact on the genre.

I posed these thoughts on my Tumblr blog and my private SF-workshop alumni group, who quickly engaged in vigorous discussion of the topic. A few very smart insights from their responses:

A theater-program director and author added more authors to my abbreviated list: Daniel Jose Older, Malka Older, Nisi Shawl, Octavia Butler, Ursula Le Guin, Amal El-Mohtar, Ted Chiang, Delia Sherman, Ellen Kushner, Sarah Pinsker, China Mieville, and Samuel Delany. We could go on for days, but that list, alone, is solid argument against the notion that progressive-change-oriented SF isn’t being written or published.

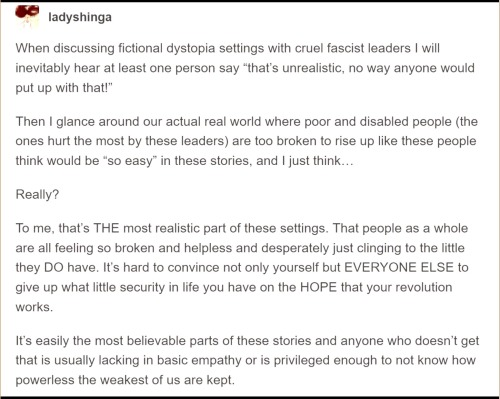

The Tumblr blogger @saffronhare says, “I’m commenting here not as a literary scholar or even as a person who reads a wide variety of SF, but I am a professional communicator. Part of what I think happens is that storytellers bring an audience through certain levels of agreement and acceptance in the process of world-building. Before we can get a person to believe in what a better future could look like, there is the work of getting that person to agree on the extreme effed-up-ness of things.” Great point! I suspect this is a major reason we see so many more dystopias than utopias.

A former NASA geologist and professor (now SF author) adds, "many of these stories are indeed being written. They just can't get published. Many of the stories appearing in mainstream lit are in fact written by self-proclaimed SF folk that couldn't get their stuff published by the supposed SF publishers." This suggests that the age-old problem of publishing's conservatism is part of the problem, rather than the genre-mindset itself.

The author who blogs under @copperbadge sent a link to this fantastic piece on the subject, addressing the importance of empathy in SF, and “meditating on why so many scifi writers appear to be so conservative.” From near the conclusion (my bolding):

“You can’t control the future. There are too many variables. And if you can’t control the future, but you desperately want to, the next instinctive, illogical step is to prevent it from happening. Keep things the way they are. Maintain the status quo and you don’t have to worry. Ray Bradbury likened social justice to censorship, and was violently opposed to his book about censorship being turned into an e-book that literally could not be burned. Orson Scott Card is terrified that legalising gay marriage is going to screw up the social fabric of the entire country, despite the fact that gay people were happily cohabitating with each other long before he was born and will be long after he is dead. Science fiction writers don’t automatically want to see the future. Some want to script it. Some think the only way to do that is to prevent it from happening.” A great read!

Along those lines, I’d like to share a book that does strive to provide visions of a positive future: Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future (I mean, it’s even in the title), put together by Kathryn Cramer and Ed Finn, the founding director of the Center for Science and the Imagination at Arizona State University, which provides great support for their SF center (and one of members of our new International Science Fiction Consortium). That project proves it’s possible to write excellent future-leaning SF that isn’t dystopian.

Another alum wrote, "One of the problems is the intersection between forward-thinking literature and experimental literature. Often the best examples of literature of change are the least accessible. Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice was a tough read for me. Because I've lived my life in a society mostly dominated by men, but making space in language for women, reading her book with the default of female pronouns was difficult. [...] I presumed that the most exciting literature of change, the most progressive in the genre, would not be best-sellers. Then I looked up Ancillary Justice and Slaughterhouse Five. Both were best-sellers. [...] When the majority of writers are the ones in positions of privilege (who list no women writers or writers of color as influences on their work), we are not going to see as much writing exploring gender, race, class, etc."

This last observation points to the problem rests on societal issues rather than the genre. In fact, the genre has often been the first to call out those very problems: How often do we use “Orwellian” these days? Or refer to Fahrenheit 451? Or any of the vast back-catalog of speculative fiction which has shaped how we view not only the future but also the world we live in? We cannot accurately predict which of our contemporary works will endure the test of time, or shape the future.

Back to the original question: Why does SF so often appear to not address (especially in utopian ways) progressive social change? Partly it’s because it’s really tough to create realistic worlds that demonstrate such change, partly because humans are kind of terrible. But largely it’s because, like anything humans do, 90% of it is crud. And unless you’re deeply involved in any genre, you only encounter the best work by accident.

I believe it’s safe to say that SF doesn’t shy away from the tough questions, the big criticisms, or exploring all aspects of change. It is the literature of the human species encountering change.

In "How America's Leading Science Fiction Authors Are Shaping Your Future" (May 2014 Smithsonian), author Eileen Gunn writes, "Science fiction, at its best, engenders the sort of flexible thinking that not only inspires us, but compels us to consider the myriad potential consequences of our actions. Samuel R. Delaney, one of the most wide-ranging and masterful writers in the field, sees it as a countermeasure to the future shock that will become more intense with the passing years. 'The variety of worlds science fiction accustoms us to, through imagination, is training for thinking about the actual changes - sometimes catastrophic, often confusing - that the real world funnels at us year after year. It helps us avoid feeling quite so gob-smacked.'"

She quotes MIT professor and engineer Sophia Brueckner, who "laments that researchers whose work deals with emerging technologies are often unfamiliar with science fiction: 'With the development of new biotech and genetic engineering, you see authors like Margaret Atwood writing about dystopian worlds centered on those technologies. Authors have explored these exact topics in incredible depth for decades, and I feel reading their writing can be just as important as reading research papers.'"

In her speech at the National Book Awards, when she was awarded the 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, Ursula K. Le Guin said, "Hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom. Poets, visionaries, the realists of a larger reality."

This is what science fiction does, and why it has remained at the center of my life for as long as I’ve been a self-aware being. And why I made it our SF center’s mission to “Save the World Through Science Fiction!”

Now that I feel this is complete enough to blog here, I'd love to hear your thoughts on this discussion, as well!