Here’s Looking at Him: Humphrey Bogart

Here’s Looking at Him

February 4, 2011By HOLLY BRUBACH

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/06/books/review/Brubach-t.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all

Has any leading man ever made women work so hard to get his attention? There he is, just minding his own business when along comes some dame who gets it in her head that they should fall in love. She flirts with him, kisses him first, talks back when he tells her off, stays when he buys her a ticket to go. He puts up a fight with all the grim resolve of a guy closing the shutters on a storm that’s about to raze his house. Sooner or later, the dame, who happens to be beautiful, wears him down and he comes around, against his better judgment. Humphrey Bogart’s shell was “a carapace,” as Stefan Kanfer writes about one of his roles, “meant to cover the psychic injuries of a decent man trying to forget the past.”

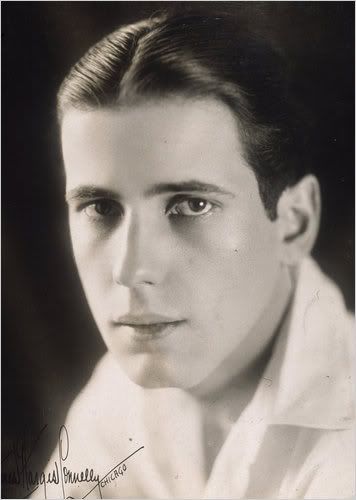

Experience had engraved itself on his face. By the time his film breakthrough came, he was 42 and already wearing the vestiges of betrayal, loss and resignation that would bring the shadow of a back story to every role he played. Photographs of Bogart in the 1920s, when he was in his 20s, show a bright-eyed, smooth-cheeked actor whose features haven’t set yet. The transformation took place before we made his acquaintance. The Bogart we came to know on the screen was mature when he arrived, with compressed emotions, an economy of gesture and a compact grace in movements that were wary and self-contained, as if all the world were not a stage but a minefield. Kanfer’s book takes its title from Raymond Chandler, who approved of the decision to cast Bogart in “The Big Sleep” as Philip Marlowe, the hard-boiled detective he had created, because Bogart could be “tough without a gun.”

Kanfer recounts Bogart’s own back story, the life that loomed just behind the acting. Such a steady diet of disappointment, failure and alcohol would be enough to relieve any man of his hopes and disabuse him of his faith in human nature. The star who made a name for himself playing gangsters, convicts, private investigators and boat captains for hire came from a family in the New York social register. The son of Belmont DeForest Bogart, a physician and a graduate of Columbia and Yale, and Maud Humphrey, he repeatedly failed to live up to his parents’ expectations and flunked out of prep school at Andover. A stint in the Navy in World War I brought time in the brig, a demotion in rank and no action overseas. As an actor, he found work on the stage, but fame eluded him; between jobs, he played chess for 50 cents a game in the arcades on Sixth Avenue. His father became addicted to morphine and died leaving $10,000 in i.o.u.’s, which Bogart paid. His three disastrous marriages before the one to Lauren Bacall fell into a pattern of professional rivalry (his wives were all actresses) and resentment, sometimes building to loud late-night arguments punctuated by flying ashtrays and the sound of broken glass. (His third wife, Mayo Methot, whom he nicknamed Sluggy, stabbed him with a knife.)

Time and again, Bogart was cast as a man of principle, and his finest qualities are on display in “Tough Without a Gun”: his decency and courage in championing Fatty Arbuckle, Peter Lorre, Joan Bennett and Gene Tierney when they were in dire straits and out of favor; his generosity to charities; his integrity in a town where promises were forgotten, not kept. Still, some angles are unbecoming. Crusading against the witch hunt conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee, he flew to Washington along with colleagues from the movie business to testify in defense of the First Amendment, but later rescinded his support when he discovered that several of his fellow protesters had in fact been affiliated with the Communist Party. When his mother, an emotionally distant feminist, died after a long career as one of the most successful commercial illustrators of the time, he listed her occupation as “housewife” on the death certificate. Insistent on Bacall’s fidelity, he carried on a long affair with his personal hairdresser.

And then there was the drinking. In an era when people drank a lot, Bogart drank more. “The whole world is about three drinks behind,” he complained. Not that he was willing to pause and wait for the world to catch up. He drank right along with Mayo during her steep descent into alcoholic psychosis. As one of the founding members of the Rat Pack (christened by Bacall), he built the booze into his charisma.

So strong is the force of Bogart’s presence on screen that his performances induce a kind of double vision: we’re watching Rick, or Sam Spade, or Captain Morgan, and Humphrey Bogart at the same time. Kanfer, who has written biographies of Groucho Marx, Lucille Ball and Marlon Brando, is at his best examining the ways Bogart’s life and his performances converged. His WASP roots paradoxically worked in his favor in gangster roles, Kanfer contends. While Jimmy Cagney and Edward G. Robinson claimed the ethnic ends of the spectrum, representing “immigrants, or the children of immigrants, who had taken a wrong turn,” Bogart stood in for Baby Face Nelson, Pretty Boy Floyd, John Dillinger, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow - “notorious malefactors from the heart of the heart of the country.”

The sudden violent flashes of anger, the bitter sense of defeat running just beneath the stoic surface seem to have been imported wholesale from Bogart’s life into the role of Dixon Steele, the broken-down screenwriter at the vortex of “In a Lonely Place.” Bogart screened “A Star Is Born” (the Janet Gaynor-Fredric March version) every year on his birthday, “with tears streaming down his face at the fate of Norman Maine,” a former matinee idol down on his luck and forgotten. “I expected a lot more of myself,” Bogart told the writer and director Richard Brooks, who was present on several of these occasions, “and I’m never going to get it.”

Kanfer’s bibliography lists two dozen books devoted to Bogart, and that’s not counting the study of his mother’s work or the memoirs of his colleagues. Why another one, and why this one? Kanfer makes the case, mustering superlatives: Bogart, “the most imitated movie actor of all time,” “the highest-paid actor in the world” (in 1946), “the most important American film actor of his time and place.” And, evidently, the most influential from beyond the grave: in his “extraordinary afterlife,” Bogart has inspired Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Paul Belmondo (“Breathless”), François Truffaut (“Shoot the Piano Player”), Woody Allen (“Play It Again, Sam”), Mos Def and Taye Diggs (“Brown Sugar”) and Thomasville Furniture (the Trench Coat Chair). Bogart’s enduring place in the culture has been secured not only by his skills as an actor, Kanfer argues, but by our chronic nostalgia for his brand of masculinity. A chorus of sources in the industry confirms the recent dearth of the “man’s man.”

Kanfer agrees that there will never be another Bogart, that there can’t be another Bogart, but not - or not only - because guys have gone all sensitive and tentative. Instead, he attributes the demise of manhood as a Hollywood ideal to the demographic shift in audiences and lists as evidence the 20 top-grossing films of all time, from “Avatar” to “Finding Nemo” - every one of them aimed at a junior audience. He cites results of surveys that measure filmgoing by age, with those in the 14-17 category seeing more than twice as many movies as those over 50. “Small wonder, then,” he concludes, “that producers keep coming up with products that border on the puerile - and with boy-men to star in them.” This makes sense but goes only so far. Consider the recent spate of late-middle-age romantic comedies and end-of-life buddy films, clearly intended for the boomer market and featuring Jack Nicholson, that superannuated adolescent, and other leading men soon to be eligible for Medicare, playing characters in whom an inability to commit and bewilderment at the state of their own lives are meant to be endearing.

The real reason there will never be another Bogart lies embedded in Kanfer’s account of his career as it was shaped by the anxieties of a nation mired in the Great Depression, sending its sons and husbands off to a far-flung war. Bogart became the model of the man circumstances demanded, a reluctant everyday hero who finally rises to the occasion when pushed too far. The age-old debate about nature versus nurture overlooks the role of culture, and Bogart, both on and off the screen, is testimony to the fact that we become who we are in response to the times in which we live, that the times favor some traits, some people - and some actors - over others.

Bogart’s appeal was and remains completely adult - so adult that it’s hard to believe he was ever young. If men who take responsibility are hard to come by in films these days, it’s because they’re hard to come by, period, in an era when being a kid for life is the ultimate achievement, and “adult” as it pertains to film is just a euphemism for pornography.