FINALLY THE LONG AWAITED EXTENSION TWO ESSAY!

{The critic has to educate the public; the artist has to educate the critic}

It is the tendency of literary criticism to remove the author from a place of authority in order to search for the meaning in a text. In our post-modern age, the resulting pluralism that arises from this critical perspective makes it difficult for any critic to discuss any text with the confidence that their interpretation is true to the text’s ‘real’ intention.

This hermeneutic approach began to emerge at the time of the trials of the literary figure Oscar Wilde. In 1895 Wilde was charged with gross acts of indecency in a trial that made his text The Picture of Dorian Gray famous in literary circles because of the so-called immoral themes that it was said to display. During the first of three trials, The Picture of Dorian Gray was critically analysed in the form it was published in by Ward, Lock and Co. in April of 1891 from a highly metaphorical and allegorical perspective, which proved detrimental to the aesthetic and philosophical perspective Wilde had on his own text. In this trial, the ontological status of literature and art came under scrutiny by the judicial process, which passes judgement on real life. The boundaries between art and reality became so blurred that an author’s fictional characters became real life evidence submitted in court which would eventually send a man to a real life prison. This kind of literary dissection is usually applied to authors subjected to posthumous biographical examinations and resurrections of their texts. However, in the case study of Wilde’s trial, the opposition farcically presented Wilde as the official custodian of the text’s dominant interpretation, while simultaneously undermining his authority on his own text. The critical perspectives adopted by the court, and at large by modern society as a result of this paradigmatic shift in hermeneutic principles, deserve close scrutiny.

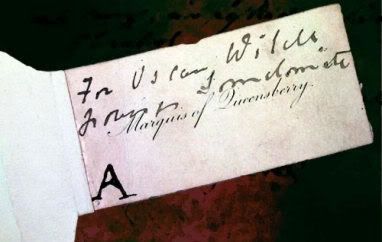

The trial in which Wilde’s literature was used as evidence was the libel suit filed by Oscar Wilde against John Sholto Douglas, Marquis of Queensberry. Wilde was encouraged by his lover, (the Marquis’ son Lord Alfred Douglas) to sue the Marquis on grounds of defamation regarding a card the Marquis had left at the Albemarle Club. Edward Clarke outlined the incident in the opening speech for Wilde:

‘That libel was published in the form of a card… and it had written upon it certain words which formed the libel complained of… "Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite [sic]."’

In order to prove the Marquis’ libel was false, Wilde was cross-examined and required to prove his innocence. In his plea the Marquis raised the issue of the novel:

‘The said Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde in the month of July in the year of our Lord One thousand eight hundred and ninety did write and publish and cause and procure to be printed and published with his name upon the title page thereof a certain immoral and obscene work in the form of a narrative entitled ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’ which … was understood by the readers thereof to describe the relations intimacies passions of certain persons of sodomitical and unnatural habits tastes and practices.’

The defence preoccupied themselves with treating Wilde’s fictional characters as character witnesses, aiming to present Wilde as the immoral personality the Marquis’ libel and plea accused him of being. It was during this libel case that the defence operated within a critical paradigm that highlighted an ambiguously homosexual allegory in The Picture of Dorian Gray. Wilde was accused of inserting biographical excerpts into the text in order to corrupt, pervert and ‘influence’ the public. The Marquis claimed that the ‘libel was true and that it was for the public benefit that it should be published.’

Wilde withdrew his complaint once it became apparent that the defence had substantial evidence that would be detrimental to his public reputation. After the libel action was dismissed Wilde was advised to leave the country, which he refused to do. A warrant for his arrest was applied for, and Wilde attended a second trial on April 29, 1895 in which his artistic philosophies were further examined. The final trial took place on May 25, 1895, where Wilde was convicted under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, and charged with gross acts of indecency. He was sentenced to two years hard labour, a sentence the judge described as ‘totally inadequate for a case such as this’ . The Marquis’ intent in publishing the libel had come to fruition; The Picture of Dorian Gray was henceforth branded with Wilde’s conviction in a similar manner as the infamous Yellow Book. Wilde was tried on the basis of numerous witness statements in the criminal trial, but it was society’s perception of Wilde as an influential homosexual criminal that ultimately led to his conviction.

Wilde was an individual who did not conform to the social and moral conventions of the time. As a result, his artistic construct was subjected to the same level of emotional and judicial scrutiny as its author, and subsequently his text has suffered a worse fate than Wilde himself. While Wilde may have died in exile in Paris, the artistic construct of The Picture of Dorian Gray remains overshadowed by the result of the third trial and the interrogation to which it was subjected in the first.

The textual content was manipulated in the first libel trial, providing a profile of Wilde that was used to characterise him in the subsequent trials. Throughout the process of cross examination in the libel trial, Wilde was asked to respond to excerpts from his texts, and in doing so, assert his philosophical and artistic position. During this process, the defence’s questions were open-ended, in the sense that they allowed Wilde to express his opinion, but subjective in that they were thematically selective, concentrating on the homoerotic elements of the text and ignoring the text’s overarching artistic and philosophic concerns. The juxtaposition of the defence’s questions with Wilde’s responses convinced the jury to accept a sordid interpretation of the text with respect to the perception of the man, as put forth by the Marquis in his libel. This manoeuvre, while technically granting Wilde an opportunity to briefly explain his philosophies and textual content from his aesthetic perspective, ultimately removed him as an authority on his own text, as the trial revealed biographical information that contradicted Wilde’s assessment of the values inherent in his published work.

As it was the aim of the Marquis’ defence to justify the claim that Wilde was a ‘posing sodomite’, they had to structure their cross-examination in a way that, although allowing Wilde freedom of speech, disempowered Wilde’s interpretation of the text. In doing this, they shifted the focus from Wilde’s perspective of his own text to that of the public’s perception of the text as homoerotic allegory.

C--A well-written book putting forward perverted moral views may be a good book?

W--No work of art ever puts forward views. Views belong to people who are not artists.

C--A perverted novel might be a good book?

W--I don't know what you mean by a "perverted" novel.

C--Then I will suggest Dorian Gray as open to the interpretation of being such a novel?

W--That could only be to brutes and illiterates.

Edward Carson, the defence for the Marquis, read at length from a passage of Dorian Gray in which the character Basil Hallward recounts his first encounter with Dorian Gray and finds himself incredibly inspired by the beauty of Dorian’s face and personality. Carson then asked Wilde for his interpretation:

C--Now I ask you, Mr. Wilde, do you consider that that description of the feeling of one man towards a youth just grown up was a proper or an improper feeling?

W--I think it is the most perfect description of what an artist would feel on meeting a beautiful personality that was in some way necessary to his art and life.

C-- You think that is a feeling a young man should have towards another?

W--Yes, as an artist.

…

C--Then you have never had that feeling?

W--No. The whole idea was borrowed from Shakespeare, I regret to say-yes, from Shakespeare's sonnets.

C--I believe you have written an article to show that Shakespeare's sonnets were suggestive of unnatural vice?

W-On the contrary I have written an article to show that they are not. I objected to such a perversion being put upon Shakespeare.

Although Wilde emphasised his attention to artistic detail in the works and his fascination with beauty, the questions posed to him in a judicial environment requiring a specific answer meant that Wilde was only able to express himself in relation to the criteria the Carson had provided for him. This shift in power meant that the focus of the criticism moved from an author-centred reading of the text to a reader-centred reading. The critical paradigms of the nineteenth and early twentieth century were undergoing a shift, undermining the omnipresence of the author and replacing the his or her authority with a biographical and psychoanalytic analysis of the allegory present in the text and thereby privileging the reader.

Wilde’s objection ‘to such a perversion being put upon Shakespeare’ is ironic, as the way in which Shakespeare’s character Hamlet was later psychoanalysed by Freud and published in Interpretation of Dreams (1899) is similar to the way in which Wilde and his characters was examined, and is evidence of the paradigmatic shift of critical theory at this time.

Austro-German sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing wrote Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), a text that was read by both Wilde and Freud before the trials . ‘The book and others of its ilk had another consequence: they formalised and popularised the idea that homosexuals are constitutionally different from heterosexuals, that their minds and sometimes even their bodies set them apart from the heterosexual majority. Ulrichs was the first to articulate this idea in print, but psychiatrists learned about it from Krafft-Ebing. The idea was popular among psychiatrists and homosexuals, but for different reasons.’

Krafft-Ebing’s theory of homosexuality as ‘sexual inversion’ in the foetal stage was evolved later in Freud’s theory that homosexuality was a ‘psychological problem’. Freud and Krafft-Ebing belonged to the Vienna Neurological Society in which both psychoanalysts spoke regarding homosexuality at the end of the nineteenth century. Freud said of Ebing’s text, ‘…this provided new valuable evidence that the soundness of my material is provided by its agreement with the perversions described by Krafft-Ebing.’ Krafft-Ebing’s text, published before the trials, was a published record of the opinion toward homosexuality at the time, namely that it was abhorrent due to the inability of the act to result in procreation. ‘The case histories represent the general level of descriptive approach of the day…The historical document is, then, a relic of the attempts in the late nineteenth century to bring the facts on man’s psychopathic sexuality to the light of thoughtful exposure.’ The confidence the defence had in claiming Wilde’s characters were immoral, was built upon an increasing understanding of psychoanalytic criticism at the time of the trial.

P. Thurschwell notes in her assessment of the ‘spectre’ of ‘Wilde’s corrupting influence’ in Literature, Technology and Magical Thinking (2001) that ‘the paradigm shift around male homosexuality, that Foucault and others have located in the late nineteenth century, intersects significantly with the popular and scientific debates about suggestibility.’ This debate regarding ‘suggestibility’ illustrates the emergence of a reader-centred interpretation of literature that encourages an individual response to texts without considering the intent of the author. While it is unavoidable that every individual will have a unique response to a text, this tendency to ‘say almost anything… in any direction at all’ about a text based on our, at times, ill-conceived interpretation, results in the degradation of the true meaning of the text. To each individual, The Picture of Dorian Gray becomes a different novel, a different expression of influence, homosexuality, hedonism and morality. The perception of immoral homoeroticism the defence presented contradicted Wilde’s supposed intent, and instead embodied the pluralist approach to hermeneutic endeavour, which ultimately allowed the defence to usurp the author’s role. Society’s rejection of Wilde’s authoritative aesthetic opinions led them to believe that the thematic concern of influence in the text was, in fact, a homoerotic reference pertaining to Wilde’s love of boyish youths and his mesmerising hold over them.

Thurschwell examines the social conventions of the fin-de-siècle that ‘wound up rejecting Wilde with such vehemence.’

‘Recent critics have read the work as it appears both in the transcripts of the trials and in Wilde’s own work, as a coded expression for the rapidly opening secret of homosexuality.’

The impact of the defence cross-examining Wilde in the manner they did has been that the text, imbued with the now persuasive pluralist approach and Wilde’s conviction, can no longer be read without reference to Wilde’s private life. The danger of advocating a pluralist interpretation is that when the text is not explicit in disambiguating its textual content, critics and responders often turn to the richly detailed lives of the authors. Although they reject the author’s interpretation of the text, they do not refrain from including biographical details of the author’s life in order to support their alternative viewpoint. The introduction of these biographical aspects blurs the line between art and reality, resulting in the characters of The Picture of Dorian Gray being tried judicially along with Wilde.

Although it is undeniable that texts contain elements of reality as a result of inspiration, it is worth noting the extensive revision of the text that Wilde undertook before the second publication of Dorian Gray. Wilde first published the short story The Picture of Dorian Gray in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine on June 20, 1890. The novel was significantly revised, lengthened, and then published by Ward Lock & Co. in 1891, which is when the majority of society was exposed to it. Wilde was advised by his friend Walter Pater that some of the seemingly homoerotic references in the text were sure to insult conventional society when the play was read. The majority of the revisions pertain to the character of artist Basil’s idolisation of the young man Dorian. Wilde’s revisions reduced the degree of flagrant homosexual ‘Greek’ love Basil had for Dorian, but did not entirely remove the degree of worship the defence for the Marquis addressed in their cross-examination. Had Wilde unintentionally included aspects of his real life that he felt were too revealing and did not adhere to the aesthetic principles he was intent on exploring in the novel, he would have removed them entirely.

Wilde’s lawyer Edward Clarke attempted to demonstrate that Wilde’s frequent references to his love life were in fact demonstrations of his aesthetic values. He failed in this endeavour. He produced a letter that had been the source of homosexual blackmail and attempted to illustrate that some clearly allegorical phrases were capable of being viewed in an artistic light, just as The Picture of Dorian Gray was justifiably capable of being viewed as an aesthetic treatise rather than a biographical artefact. However, the letter was incapable of being viewed as a fictional construct as Dorian Gray was, and so his efforts were wasted.

‘The words of that letter, gentlemen, may appear extravagant to those in the habit of writing commercial correspondence … but Mr. Wilde is a poet … and is prepared to produce [it] anywhere as the expression of true poetic feeling, and with no relation whatever to the hateful and repulsive suggestions put to it in the plea in this case.’

Clarke also quotes Wilde in the opening statement as saying, ‘I look upon it as a work of art’. Clarke read aloud:

‘…it is a marvel that those red rose-leaf lips of yours should have been made no less for music of song than for madness of kisses. Your slim gilt soul walks between passion and poetry. I know Hyacinthus , whom Apollo loved so madly, was you in Greeks days. ’

The letter quoted above contains allusions to Greek homoeroticism and refers directly to Lord Alfred Douglas. The letter, which is signed ‘Always, with undying love, Yours, Oscar’, is a transparent and direct reference to the homosexual relationship between Wilde and Douglas. Edward Carson for the defence retaliated to this:

‘The turning of one of Wilde's letters to Lord Alfred Douglas into a sonnet was a very thinly veiled attempt to get rid of the character of that letter.’

The inclusion of this letter did little more than potentially damage the credibility of Wilde’s later argument. The ‘thinly veiled attempt’ insulted the jury’s intelligence, and was not effective in presenting Wilde as a man prone to including unintentionally homoerotic references in his text - the letter was seen for what it was, a letter of homoerotic admiration for Lord Alfred Douglas, and in the light of this litigious mishap, The Picture of Dorian Gray was shown no mercy.

The letter, among other character witnesses utilised in the second and third trials, left no doubt in the minds of the jury that Wilde was not only guilty of posing as a sodomite, but was guilty of being an active homosexual. But although the letter was significant proof of this, The Picture of Dorian Gray was not. The difference between the two texts is that in the letter, there is no pseudonym, no attempt other than allusion to Greek mythology to disguise the reality of Wilde’s word. In The Picture of Dorian Gray, the novel is capable of existing without any personal explanation as to the textual content from the author, and so can be considered an artistic construct where the letter cannot.

Unfortunately the novel was subjected to the same degree of biographical examination as an artefact of real life, as shown in the extensive reference to the novel in biographies. Neil McKenna’s aim in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2003) was to explore Wilde’s sexual history, to ‘tell [that] story, to chart Oscar’s odyssey to find his true sexual self’ and ‘go beyond the mythology and misapprehensions … to present a coherent and psychologically convincing account of his sexual journey’ is one of many that includes detailed references to The Picture of Dorian Gray.

While the trials featured many of Wilde’s previous lovers, one man that avoided detection was John Gray. Although he managed to keep his name out of the trial, John Gray had, once upon a time, claimed credit for his part in inspiring the artist Wilde. Wilde met ‘an ideal boy, in the form of John Gray, a young poet who was to become the inspiration for one of Oscar’s most famous and beguiling creations, Dorian Gray.’ McKenna asserts that ‘there could be no doubt in the mind’s of Oscar’s friends and contemporaries that John Gray was the model for Dorian Gray.’ Contemporary of Wilde, Lionel Johnson wrote, ‘I have made great friends with the original Dorian: one John Gray, a youth…’ and Arthur Symons remarked, ‘I was not aware he was supposed to be the future Dorian Gray of Wilde’s novel.’ A letter from Gray survives, the youth signing it in the name of ‘Dorian’, and Wilde frequently referred to Gray as Dorian during conversations. It was accepted amongst the contemporary society of Wilde that there was some real life inspiration, if not explicit reference to reality, within his novel. Based on the evidence proffered in the trial, it is very probable that John Gray was as close to real life as the fictional construct of Dorian Gray could be.

The numerous testaments of Wilde’s previous lovers and hired boys proved beyond reasonable doubt that Wilde was guilty not only of ‘posing’, but acting, as a sodomite. The defence for the Marquis did not need to engage with the novel in order to prove this. The link drawn between the text and Wilde’s personal life in the trial opened the door for critics and biographers of Wilde to draw comparisons between the art and reality to the detriment of the original text. The characters of Dorian Gray, Lord Henry and Basil Hallward are reduced to nothing more than simulacrums of Wilde when examined in this manner. Although not made explicit in the trial, the defence insinuated that the passions of Basil for Dorian were the same as Wilde had experienced for Douglas, or other unnamed youths. McKenna has made explicit in his work the link between Wilde and John Gray, and has based this on the recurring theme of influence in the text. This sordid, psychoanalytic interpretation of the text has been taken up by biographers, including McKenna, who aimed at constructing a crude and sexual version of Wilde in conjunction with that of the text, inextricably linking fiction with reality.

The defence and McKenna favour the interpretative, metaphorical reading of the text which they assumes alludes to more than ‘what an artist would feel on meeting a beautiful personality that was in some way necessary to his art and life’ . In his text McKenna writes:

‘Indeed Oscar takes the metaphor of anal sex and penetration even further in Dorian Gray…It involves a kind of spiritual sodomy:

‘To project one’s soul into some gracious form, and let it tarry there for a moment; to hear one’s own intellectual views echoed back to one with all hew added music of passion and youth; to convey one’s temperament into another as though it were a subtle fluid or a strange perfume; there was a real joy in that perhaps the most satisfying joy left to us in an age so limited and vulgar as our own.’

Lord Henry wants to ejaculate the very essence of his soul into Dorian’s gracious form like a ‘subtle fluid’, just, perhaps, as Oscar wanted to inseminate John Gray with his own combination of subtle intellect and seminal fluid. ’

McKenna’s subversive and perverted authoritative stance is a learned one, based on the ways of thinking that had fully developed after the fin-de-siècle. The way in which McKenna psychoanalysed the character of Lord Henry and applied this to his psychoanalysis of Wilde has completely removed Wilde as the author of the text and inserted himself [McKenna] as the chief authority on the characters and the textual content, an action strikingly similar to that of the defence for the Marquis in the previous century, but based upon the theory in Roland Barthes’ The Death of the Author (1967). Barthes asserts that the author as an authority should not be considered in order to properly deduce the meaning of the text. Art is a separate entity, as writing is ‘the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin. Writing is that neutral, composite, oblique space where our subject slips away, the negative where all identity is lost, starting with the very identity of the body writing. ’ This view, published in 1967, is similar to the actions of the defence seventy years earlier, substantiating that critical hegemony was an idea that developed towards the end of the nineteenth century, evolving into the idea that is ingrained in our consciousness to the repeated detriment of the authors of the texts we read today.

Similar to the pluralistic and interpretative stance taken by the defence in 1895, The Yale School of deconstructionist literary theorists argued in the 1960s and 1970s against the author as an authoritative figure. They encouraged a pluralist interpretation of literature that is reader-centred. The idea that the author has little control over the reception of their work continued to evolve until it developed into the idea that the author need not be consulted when critiquing a text. This poststructuralist approach to critically scrutinising literary texts is one result of the court case that set the precedent for responding to The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The rejection of the author gives complete power to the reader, and because of this, whatever meaning originally intended is twisted, reinterpreted, and represented, highlighting different aspects of the text as they appeal to individuals over time. A particular theme of concern is that of influence, largely explored in The Picture of Dorian Gray as the catalyst in Dorian’s personality. It was mainly interpreted, as McKenna illustrated, as the influence between an older, dominant homosexual and a younger, inexperienced one, much like the relationships Wilde was revealed to have pursued. As Thurschwell says, however, ‘homosexual sexual conduct by no means exhausts the meaning of the term [influence].’ The defence’s and McKenna’s interpretation of the influence in the novel degrades the spiritual term to a sordid level, a metaphorical method of interpretation Paul de Man examined in 1973. De Man asserts that society has a tendency to ignore the importance of grammar when responding to texts, instead paying higher authority to the secondary, metaphoric interpretation.

Similarly, C.G Jung states in On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry (1922), that psychoanalytic criticism in literature is ill-fitting for the subject matter, because ‘a scientific attitude will always tend to overlook the peculiar nature of these more differentiated states in favour of their casual derivation, and will endeavour to subordinate them to a general but more elementary principle’. It is this ‘casual derivation’ based on the defence’s inclination toward a metaphoric interpretation that results in a sordid representation of Dorian Gray. ‘This lack of delicacy seems to be a professional peculiarity of the medical psychologist, and the temptation to draw daring conclusions easily leads to flagrant abuses. A slight whiff of scandal often leads spice to a biography, but a little more becomes a nasty inquisitiveness - bad taste masquerading as science.’ The defence for the Marquis possessed this ‘nasty inquisitiveness’ in 1895, but it is the tendency of contemporary critics to also adopt this mode of psychoanalytic interpretation. The revered place the author once resided in has been demolished by the self-motivated, reader-centred manner of interpreting texts.

It is possible to analyse a text and develop an individual response to a text without making subversive and unfounded claims about the novel and the author. The mistake McKenna and many others have made in analysing The Picture of Dorian Gray is that they explicitly relate the analysis of the characters to their analysis of Wilde. Analysing Dorian Gray solely as a literary device and not as reflection of Wilde’s character reveals him to be a victim of a Faustian bargain. The agreement in which his soul is traded for his superficial beauty results in the disfiguring absence of soul within Dorian, which forces even Lord Henry to question whether even his adulterated influence of Dorian could have resulted in such corruption.

The denouement of the novel ultimately tells a moral tale in which the immoral epicurean individual is punished by his vices. As the Christian Leader said in their review 3 July, 1890, ‘even its most powerful passage is of small account compared with the motive dominating the writer…We can only hope that it will be read and pondered by those classes of British society whose corruption it delineates with such thrilling power.’ Similarly, and more poignantly due to its focus on Wilde, was the review from i>The Christian World, 10 July 1890 which says clearly, ‘if we did not know the author’s name, and skipped one or two phrases [The Picture of Dorian Gray] would strike us as a ‘moral tale’, intended to excite a loathing for sin.’ It is entirely possible to analyse the character within the context of the novel without psychologically drawing information from the author. It is not, as Barthes advocated, removing the author, because viewing the character within the context of the novel acknowledges the author’s input into the character. Unnecessarily, Wilde and indeed many authors (dead or alive) have found themselves defenceless against the onslaught of varying forms of psychoanalytic criticism when really all that was required was insight into the character as a literary figure, not as a reflection of the author.

The tendency of literary criticism to remove the author from a place of authority essentially began as a result of a paradigmatic shift at the end of the nineteenth century, but has evolved into the highly psychoanalytic way in which we tend to respond to texts today. The subversive methods of interrogation used by the defence counsel against Wilde during his libel trial in 1895 ultimately disempowered him as the authority on his own text. The defence’s shortcoming in psychoanalysing the text has altered the perception and reception of the text henceforth. The Picture of Dorian Gray is now tainted with the outcome of the trial and responders today are reading a text entirely different from the aesthetic, moralistic and philosophical text that clearly exists beneath the bias created by the result of the trial. The novel and its perceived thematic concerns may exist today, but the original literature is dead.

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity's long-broken urn,

For his mourners will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

Word Count: 4,806

I tried to put in all the formatting, but it is 11pm and I'm tired. There's no reflection statement and I think the paragraph on John Gray still needs to be tweaked, but here it is after 11 months. Two weeks away from submission, folks!

Any feedback is appreciated. I know it's long, but any comments are greatly appreciated!