Kuttner Quest!

Over the last several years I've been collecting Henry Kuttner's stories wherever I can find them. I must have 10 or more paperback anthologies of his, and I believe I have every science-fiction novel he published in the 60s as well as a few of his mysteries. Much of this work was produced in tandem with his wife, fellow pulpster C. L. Moore and published under the names of one or both authors, or perhaps a bevy of pseudonyms like Lewis Padgett or Keith Hammond. Together, the two created some of the most beloved and classic science fiction and fantasy yarns of the pulp era, but of late I've been more interested in the works credited solely to Kuttner or works he published before he and his wife became writing partners.

The literary rap on Kuttner sans Moore, as expressed by Sam Moskowitz in his seminal Seekers of Tomorrow is that Kuttner didn't really have a literary style of his own, but rather was so adept a craftsman that he could ape whatever style an editor might want. Need him to write a Stanley G. Weinbaum story? Kuttner's your man. Want to publish A. Merritt's Dwellers in the Mirage but can't get the rights? Kuttner will whip up The Dark World in a jiff!

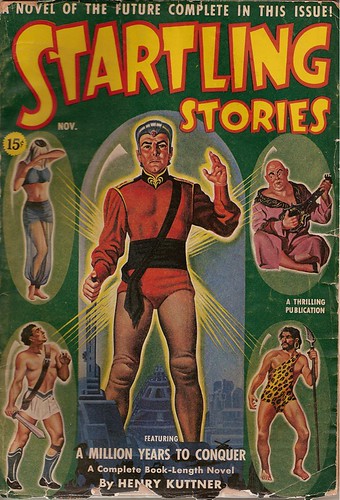

I detect some basis for this criticism in some of the Kuttner work I've read to date, but I suspect it's another piece of "common wisdom" about a pulp writer that will turn out to be bullshit once you read a decent sampling of the author's output. Many of Kuttner's stories do have a Merrittesque tone, but I wonder if that's not just a tell that Catherine worked over a certain descriptive passage. "Lord of the Storm," from the September 1947 issue of Startling Stories, is a fairly standard potboiler future apocalypse novel, but there are moments were the lush description kicks into overdrive strongly reminiscent of similar passages in Moore's Jirel of Joiry or Northwest Smith fantasies. Years after encountering C. L. Moore, I first read A. Merritt, and it was obvious that he was a major stylistic influence on Moore.

This baroque, almost self-indulgent descriptive style is absent in every Henry Kuttner story I have read that comes from the period prior to his heavy collaboration with C. L. Moore. It's not that there aren't lush descriptions, but there is a luxury of language that begins to flower after 1940, when the two were married.

Their first known collaboration occurred in 1937, with the famous "Quest of the Starstone," a fan-demanded team-up of Moore's two superstar Weird Tales characters, Jirel of Joiry and Northwest Smith. The story goes that H. P. Lovecraft put the young Kuttner in touch with C. L. Moore, whom Henry (and most Weird Tales readers) thought was a man. He wrote Moore a gushing letter of praise in 1936 that initiated a relationship that eventually bloomed into marriage.

"Quest of the Starstone" shows Kuttner's plotting and humor, and I strongly suspect that he wrote the skeleton of the story with her supplying certain descriptive details. Given that it was written perhaps a year after they met via the mail, it's easy to look at this story like a kind of Jirel/NWS fanfic written by a devoted C. L. Moore fan. It's very possible that's exactly what it is. I included the story in the Planet Stories editions of both Black God's Kiss and Northwest of Earth, and while it is a fun and engaging story the style is quite strikingly different than evident in the other "pure Moore" stories in those anthologies.

L. Sprague de Camp often recounted that once, when staying over night at the Kuttner's well into their collaboration years, he fell asleep to the sound of one partner typing a manuscript only to awake to the sound of the other partner finishing the very same story. Another oft-recounted tale involves the authors "switching off" to run and errand or go to the bathroom or something, so that not a moment was spared. One could pick up immediately where the other had stopped writing.

The (often imperfect, it must be stated) Internet Speculative Fiction Database lists the first overt post-marriage collaboration as 1941's "The Devil We Know." Scores of collaborations followed, many under the Lewis Padgett pseudonym. Still, several "pure Kuttner" stories exist after their marriage, such as 1941's Elak of Atlantis story "Dragon Moon," which shows little or no Moore influence. Moore claims in an introduction to Kuttner's Robots Have No Tails that she wrote "not a word" of his brilliant and wholly original Gallegher stories. Dozens of stories throughout the 40s and 50s until his death in 1958 were published solely under his name, but that doesn't necessarily make them "pure" Kuttner.

I'd like to read as much Moore and Kuttner as I can get a hold of, whether collaborative tales or stories produced independent of one another. For now, I've been focusing a lot of my collecting and reading on stories by Henry Kuttner prior to his marriage. Most of this material has not been reprinted since the pulp era. Some of it is a bit dreadful, it must be said. Others, including his very first story--a Weird Tales nailbiter called "The Graveyard Rats"--are considered by critics to be among the best genre stories ever published.

I'm currently building a Planet Stories anthology of Henry Kuttner's early material. Right now I'm in the research phase, buying old pulps, evaluating stories, and discovering all of the fun other stuff that comes from delving deeply into 70-year-old magazines.

I plan to share a lot of this research here on the blog, and I hope you'll find it interesting.

I welcome comments, questions, and suggestions as we go along.