tolerance at home and abroad

13 février 1900.

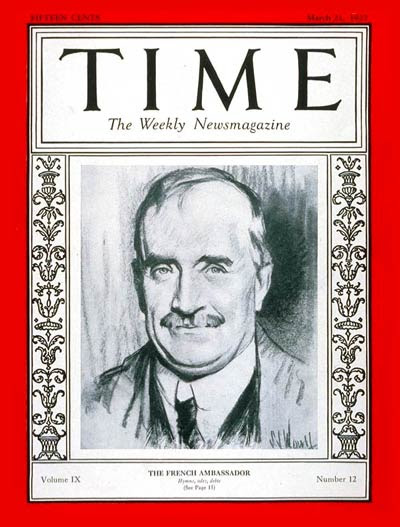

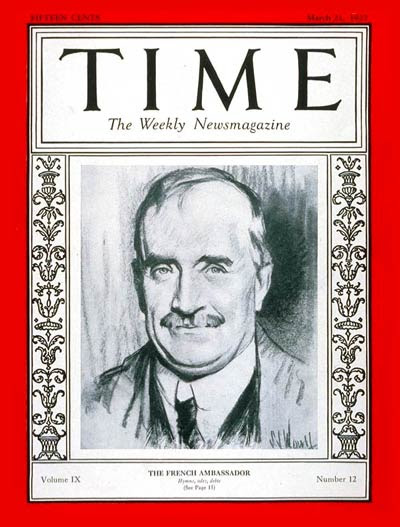

Claudel déjeune. Il parle du mal que l’affaire Dreyfus nous a fait à l’étranger. Cet homme intelligent, ce poëte, sent le prêtre rageur et de sang âcre.

-Mais la tolérance ? lui dis-je.

-Il y a des maisons pour ça, répond-il.

Ils éprouvent je ne sais quelle joie malsaine à s’abêtir, et ils en veulent aux autres, de cet abêtissement. Ils ne connaissent pas le sourire de la bonté.

Sa soeur a dans sa chambre un portrait de Rochefort et, sur sa table, La Libre Parole. Elle a envie de le suivre dans ses consulats.

Et ce poëte affecte de ne comprendre et de n’admirer que les ingénieurs. Ils produisent de la réalité. Tout cela est banal.

Il a le poil rare et regarde en dessous. Son âme a mauvais estomac. Il revient à son horreur des juifs, qu’il ne peut voir ni sentir. 13 February 1900.

Lunch with Claudel. He speaks of the harm that the Dreyfus affair caused to us abroad. This man, this poet, smells of a fanatical priest and acrid blood.

-What of tolerance? I said.

-There are houses for that, he replied.

They feel some unhealthy joy at dumbing themselves down, and they want others to follow suit. They do not know the smile of kindness.

His sister has in her room a portrait of Rochefort and, at her table, La Libre Parole. She wants to follow his consular appointments.

And the poet affects a failure to understand and admire anyone but the engineers. They produce reality. All this is commonplace.

He has thinning hair and a downcast gaze. His soul has indigestion. He returned to his horror of the Jews, whom he cannot suffer to see or smell. 13 февраля 1900 года.

Обед с Клоделем. Он говорит о том, какой вред нанесло дело Дрейфуса нашей репутации за рубежом. От этого человека, этого поэта, исходит душок изувера-священника и едкой крови.

-Ну а терпимость? спросил я.

-Есть для этого дома, ответил он.

Они испытывают какое-то нездоровое удовольствие от самоотупления, и подстрекают других к тому же. Им неизвестна улыбка великодушия.

Его сестра повесила в своей комнате портрет Рошфора, а на стол положила «Ля Либр Пароль». Она хочет следовать за ним в его консульствах.

А сам поэт делает вид, что не понимает никого кроме инженеров. Они производят действительность. Всё это пошло.

У него жидкие волосы и потуплённый взор. Его душа страдает несварением желудка. Он возвращается к своему отвращению к евреям, которых он не в силах ни видеть ни обонять.

-Jules Renard, Journal 1887-1910, Pléiade, 1986, p. 570

Claudel déjeune. Il parle du mal que l’affaire Dreyfus nous a fait à l’étranger. Cet homme intelligent, ce poëte, sent le prêtre rageur et de sang âcre.

-Mais la tolérance ? lui dis-je.

-Il y a des maisons pour ça, répond-il.

Ils éprouvent je ne sais quelle joie malsaine à s’abêtir, et ils en veulent aux autres, de cet abêtissement. Ils ne connaissent pas le sourire de la bonté.

Sa soeur a dans sa chambre un portrait de Rochefort et, sur sa table, La Libre Parole. Elle a envie de le suivre dans ses consulats.

Et ce poëte affecte de ne comprendre et de n’admirer que les ingénieurs. Ils produisent de la réalité. Tout cela est banal.

Il a le poil rare et regarde en dessous. Son âme a mauvais estomac. Il revient à son horreur des juifs, qu’il ne peut voir ni sentir. 13 February 1900.

Lunch with Claudel. He speaks of the harm that the Dreyfus affair caused to us abroad. This man, this poet, smells of a fanatical priest and acrid blood.

-What of tolerance? I said.

-There are houses for that, he replied.

They feel some unhealthy joy at dumbing themselves down, and they want others to follow suit. They do not know the smile of kindness.

His sister has in her room a portrait of Rochefort and, at her table, La Libre Parole. She wants to follow his consular appointments.

And the poet affects a failure to understand and admire anyone but the engineers. They produce reality. All this is commonplace.

He has thinning hair and a downcast gaze. His soul has indigestion. He returned to his horror of the Jews, whom he cannot suffer to see or smell. 13 февраля 1900 года.

Обед с Клоделем. Он говорит о том, какой вред нанесло дело Дрейфуса нашей репутации за рубежом. От этого человека, этого поэта, исходит душок изувера-священника и едкой крови.

-Ну а терпимость? спросил я.

-Есть для этого дома, ответил он.

Они испытывают какое-то нездоровое удовольствие от самоотупления, и подстрекают других к тому же. Им неизвестна улыбка великодушия.

Его сестра повесила в своей комнате портрет Рошфора, а на стол положила «Ля Либр Пароль». Она хочет следовать за ним в его консульствах.

А сам поэт делает вид, что не понимает никого кроме инженеров. Они производят действительность. Всё это пошло.

У него жидкие волосы и потуплённый взор. Его душа страдает несварением желудка. Он возвращается к своему отвращению к евреям, которых он не в силах ни видеть ни обонять.

-Jules Renard, Journal 1887-1910, Pléiade, 1986, p. 570