family values II

― for Victor Yodaiken

ἔτι καὶ αἱ παροιμίαι, ὥσπερ εἴρηται, μαρτύριά εἰσιν, οἷον εἴ τις συμβουλεύει μὴ ποιεῖσθαι φίλον γέροντα, τούτῳ μαρτυρεῖ ἡ παροιμία, μήποτ' εὖ ἔρδειν γέροντα.

― Aristotle, Rhetoric, 1376a

Further, proverbs, as stated, are evidence; for instance, if one man advises another not to make a friend of an old man, he can appeal to the proverb, Never do good to an old man.

― translated by J. H. Freese

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, 1653, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

De quoi en effet deux hommes auraient-ils bien pu discuter, à partir d’un certain âge ? Quelle raison deux hommes auraient-ils pu découvrir d’être ensemble, hormis bien sûr le cas d’un conflit d’intérêts, hormis aussi le cas où un projet quelconque (renverser un gouvernement, construire un autoroute, écrire un scénario de bande dessinée, exterminer les Juifs) les réunissait ? À partir d’un certain age (je parle des hommes d’un certain niveau d’intelligence, et non de brutes vieillies), il est bien évident que tout est dit. Comment un projet intrinsèquement aussi vide que celui de passer un moment ensemble aurait-il pu, entre deux hommes, déboucher sur autre chose que sur l’ennui, la gêne, et au bout du compte l’hostilité franche ? Alors qu’entre un homme et une femme il subsistait toujours, malgré tout, quelque chose : une petite attraction, un petit espoir, un petit rêve. Fondamentalement destinée à la controverse et au désaccord, la parole restait marquée par cette origine belliqueuse. La parole détruit, elle sépare, et lorsque entre un homme et une femme il ne demeure plus qu’elle on considère avec justesse que la relation est terminée. Lorsque au contraire elle est accompagnée, adoucie et en quelque sorte sanctifiée par les caresses, la parole elle-même peut prendre un sens différent, moins dramatique mais plus profond, celui d’un contrepoint intellectuel détaché, sans enjeu immédiat, libre.

― Michel Houellebecq, La possibilité d'une île, Fayard, 2005, pp. 87-88

Indeed, what could two men properly discuss, starting at a certain age? What reason could two men discover for being together, excepting to be sure the case of a conflict of interests, excepting also the case where some project (to overthrow a government, to build a highway, to write a script for a comic strip, to exterminate the Jews) joined them together? Starting at a certain age (I speak about men of a certain level of intelligence, and not about aged brutes), it is quite obvious that all is said. How could a project intrinsically as empty as that of spending a while together, between two men, lead to anything other than boredom, embarrassment, and in the final analysis, open hostility? Whereas between a man and a woman there always remained, in spite of everything, a certain something: a little attraction, a little hope, a little dream. Basically meant for controversy and dissension, the word remained branded by this quarrelsome origin. The word destroys, it separates, and whenever there remains nothing else between a man and a woman, their relationship is rightly judged as finished. When on the contrary it is accompanied, softened, and to some extent sanctified, by caresses, the word itself can assume a different meaning, less dramatic but more profound, that of a detached intellectual counterpoint, bereft of an immediate stake, free.

― translated by MZ

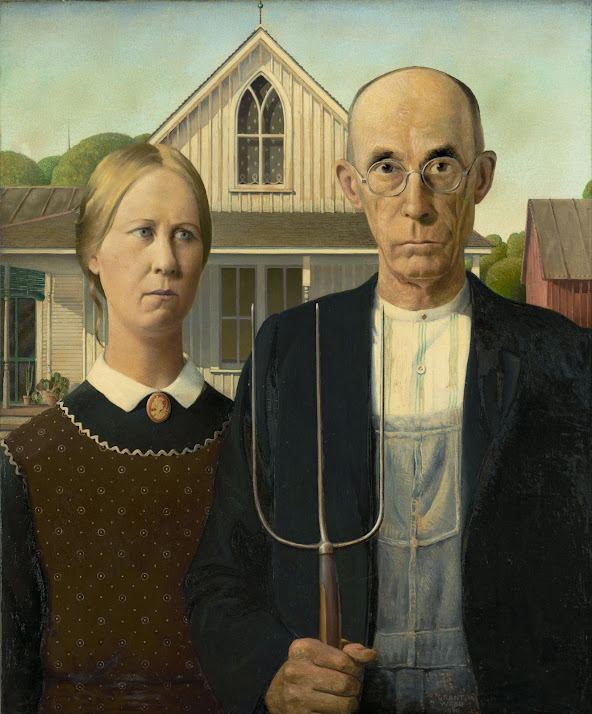

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930, The Art Institute of Chicago

Citationalism. Now that your philosophy has a name, you just need to market it a little, and those donations and tasty disciples are sure to follow.

― VJY to MZ, Wednesday, 9 July 2003, 15:41:25It is a good thing for an uneducated man to read books of quotations. Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations is an admirable work, and I studied it intently. The quotations when engraved upon the memory give you good thoughts. They also make you anxious to read the authors and look for more. In this or or some other similar book I came across a French saying which seemed singularly opposite. ‘Le cœur a ses raisons, que la raison ne connaît pas.’ It seemed to me that it would be very foolish to discard the reasons of the heart for those of the head. Indeed I could not see why I should not enjoy them both. I did not worry about the inconsistency of thinking one way and believing the other. It seemed good to let the mind explore so far as it could the paths of thought and logic, and also good to pray for help and succour, and be thankful when they came. I could not feel that the Supreme Creator who gave us our minds as well as our souls would be offended if they did not always run smoothly together in double harness. After all He must have foreseen this from the beginning and of course He would understand it all.

― Winston Churchill, My Early Life: 1874-1904, Scribner, 1996 (originally published in 1930), p. 116

If friendship is to retain any foothold amidst the depredations of age, it will be owed to the reasons of the heart, not those of the head. In the realms of middlebrow learning imparted by citationalism, men have more trouble justifying enduring erotic attachments. As Gene Simmons observes, when people say, “I want to get laid a lot and make lots of money,” they are reversing the right order. The efficient strategy of hedonism would have them cultivating wealth ― or better yet, celebrity ― as a means of getting laid a lot. (While aphrodisiac deployment of celebrity is subject to the same misgivings as similar use of wealth, sexual exploits that ensue from the former scenario enjoy the advantage of being attributable to a more or less authentic expression of oneself, rather than one’s accomplishment reduced to its most fungible denominator.) In singling out efficiency, masculine sexual ambition curtails the scope of fidelity. Promiscuity is far superior to monogamy in its capacity to fulfill the need for approval that fuels the male libido. Only a stern pursuit of some project that joins them together ― as leveraged by the pitchfork held in the foreground, as embodied in the farmhouse captured in the background ― can keep the old man content even within the favorable bounds of a May-December coupling of his American Gothic.