Deepwater Horizon

It's experiencing new levels of heartache each day, and it pulls my stomach down through my ass. I'm so fucking sick of mankind.

It's Worse Than You Think

by Devilstower

Sun May 02, 2010 at 06:00:02 AM PDT

It's easy to be pro-drilling. All it requires is a little chanting, a little pretending that somehow this activity can reverse a yawning oil deficit that's been growing since 1970, a little chest-thumping conceit that there's something patriotic or admirable about risking other people's homes, livelihoods, and lives because it pisses off the "tree huggers." All it takes is a little ignorance and a belief that any risk is worth a dime at the pumps. All it takes at turning a blind eye to the real level of danger involved.

Which is going to get a lot harder after this week.

When Deepwater Horizon exploded on April 20, attention was first focused, and quite rightly, on the 11 workers missing, all of whom are now presumed to have died either directly in the massive fireball that engulfed the ship or somewhere in the choppy oil-stained waters. The well they had been working on--which was in the process of being "capped" with concrete when the explosion occurred--wasn't considered a high risk for leakage. The smear of oil on the ocean's surface after the explosion was thought to be mostly from the fuel that had been carried by the drilling ship.

Rear Adm. Landry said no oil appeared to be leaking from a well head at the ocean floor, nor was any leaking at the water's surface. But she said crews were closely monitoring the rig for any more crude that might spill out.

About half a dozen boats were using booms to trap the thin sheen, which extended about seven miles north of the rig site. There was no sign of wildlife being affected; the Louisiana coast is about 50 miles away.

As the search for those missing workers was sadly ended, the slick around the former drill site continued to grow. It was soon clear that the initial hopes that the sinking of the drilling ship and collapse of the well structures would not lead to a prolonged leak were unfounded. What started out as a small slick directly around the drill site enlarged rapidly.

"We thought what we were dealing with as of yesterday was a surface residual [oil] from the mobile offshore drilling unit," Landry said. "In addition to that is oil emanating from the well. It is a big change from yesterday... This is a very serious spill, absolutely."

A robotic camera has determined a pipe leading from the well is leaking oil at an estimated rate of 1,000 barrels--or about 42,000 gallons a day, reports CBS News correspondent Don Teague. That's still much less than the worst-case scenario.

By comparison, Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons in Alaska's Prince William Sound in 1989--the worst oil spill in U.S. history.

That rate was certainly bad enough. The press dutifully reported this number (myself included). But within two days there was evidence that the 1,000 barrels a day didn't match up with the the actual size of the leak.

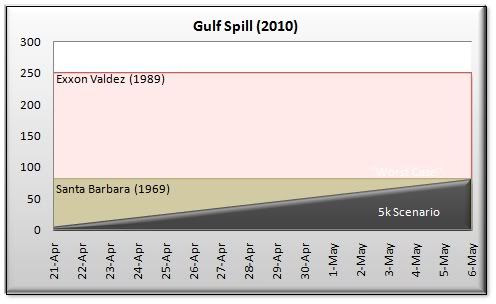

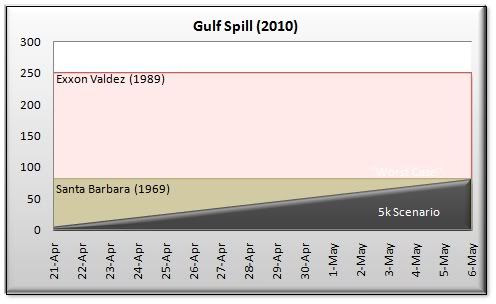

We have a visible oil slick covering 2,233 square miles (5,783 km2). Given a minimum thickness of 1 micron (see chart below), that is 5,783 cubic meters of oil, or 1,527,706 gallons (36,374 barrels). The blowout happened almost 7 days ago on April 20. That's at least 5,000 barrels of oil per day--assuming none of it was consumed during the two-day fire that raged before the rig sank on April 22, and none has been collected by the response crews that have been working diligently for days.

Government numbers were soon adjusted accordingly--though 5,000 barrels a day was the minimum amount needed to account for the visible slick on the surface. Since then the press has been using that number.

If what's actually been happening is that the well has been releasing around 5,000 barrels a day since the initial explosion, something like 60,000 barrels are now washing around the Gulf. If the well was initially producing less, and the 5k rate kicked in later, the total production should be somewhere between the 12k that would have come from the older 1,000 barrel a day estimate and the 60,000 barrels from the 5k estimate.

If the 5k rate is accurate and the rate of the spillage is steady, the size of the spill will exceed the 1969 disaster in Santa Barbara within the next week. At that rate, it will take another month for the size of the spill to reach that of the Exxon Valdez--though because of the location of this spill, clean up will not only be more difficult, but have far more economic impact than the Prince William Sound spill.

A month may seem like plenty of time to stop the flow, but so far there has been little progress at arresting the spill and BP has appealed to both competitors and the military for new ideas. While there are numerous meetings going on, several ideas have been tossed around, and some actions are underway that may retard the flow there is presently no coherent plan for arresting the spill from the sunken wellhead. Real action to address the problem may take far longer than a month.

But that's not the worst of it. With the estimated rate of spillage having now been adjusted upwards, it's clear that over the last two days the 5k rate is not enough to explain the rapid expansion of the spreading oil slick. It's becoming increasingly obvious that we don't have a month before we reach Valdez levels of disaster.

The surface area of a catastrophic Gulf of Mexico oil spill quickly tripled in size amid growing fears among experts that the slick could become vastly more devastating than it seemed just two days ago. ... The slick nearly tripled in just a day or so, growing from a spill the size of Rhode Island to something closer to the size of Puerto Rico, according to images collected from mostly European satellites and analyzed by the University of Miami.

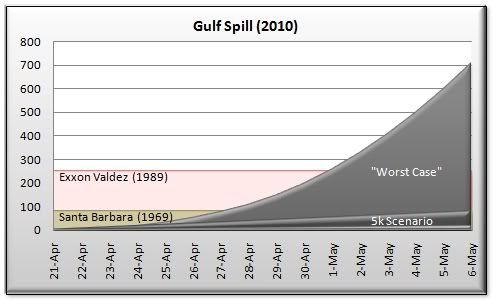

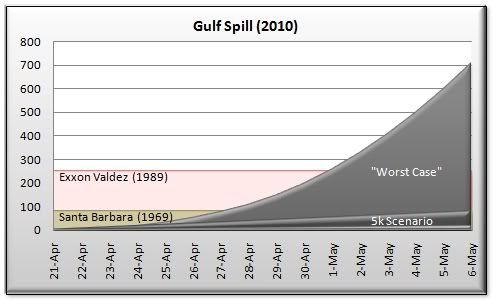

This may mean that we've simply been underestimating the size of the flow all along, that the 5k scenario undershot the actual leak. But the series of underestimates may have another cause--the size of the spill may have been growing, day by day, right from the start. The source of much of the spilled oil appears to be the damaged valves and piping in a house-sized structure on the sea floor, at a depth of 5,000'. If the openings have gradually been forced wider, the level of flow may soon reach a point where "catastrophic" seems a vast understatement.

Ian R. MacDonald, an oceanography professor at Florida State University, said his examination of Coast Guard charts and satellite images indicated that 8 million to 9 million gallons had already spilled by April 28. ... Alabama's governor said his state was preparing for a worst-case scenario of 150,000 barrels, or more than 6 million gallons per day. At that rate the spill would amount to a Valdez-sized spill every two days, and the situation could last for months.

Increasingly it appears that we are living this "worst case" scenario. If the FSU numbers are correct, we have already reached Exxon Valdez levels of spill, on our way to something much, much worse.

Skytruth, the nonprofit organization that forced both government and industry to admit the 1,000 barrel per day number was way too small has confirmed that Valdez is in the rear view.

Saturday, the group updated its analysis to estimate that the slick contained more than 11.1 million gallons of oil, which would make it the largest oil spill in American history. John Amos, the group's president, also revised the estimate of the rate of oil leaking to 25,000 barrels a day, saying it was a "rock bottom" figure.

You can track Skytruth's estimates and updates at their blog. But note that the 25k number is what would have had to spill from day 1 to match what Skytruth is now seeing on the surface of the Gulf. What's more likely based on the rate of growth seen in the visible slick is that the spill is increasing and is now well past that number.

What we are facing is something far beyond what most people would think possible for the loss of a single well. Something nearly incomprehensible. Should it continue, this will be an oily-Chernobyl for the Gulf of Mexico. Oyster beds that have been sustainably harvested for over 130 years are already being lost. Shrimpers, fishermen, businesses that depend on tourism--all are looking not toward a decline, but an end to these industries that could last for years. The loss of fisheries alone could lead to shortages of sea food worldwide and economic collapse of coastal towns.

The economic damage is only part of it. Wetlands that shelter not just endangered species, but the coasts beyond, could become dead marshes of oil-soaked stumps and the oil-soaked bodies of dead wildlife. Animals that live in the Gulf--from the smallest fish to Sperm Whales--are threatened. Both total population and diversity in and around the Gulf may be impacted for a generation.

Let's hope it doesn't happen (I know what's at the top of my prayer list this Sunday). Let's hope that the worst case turns out to be the "laughably overblown case," that even now the flow of oil is easing, and that within a week some unexpected solution is in place. Let's pray for all of that.

But here's what we shouldn't forget: even if this is solved tomorrow, even if the cause for the explosion is exactly explained, even if what went wrong this time can be safely ruled out from ever happening again, what the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon has demonstrated is that we can't allow offshore drilling to continue. Why? Look at those numbers above. That a single well has the potential to spill millions of gallons in an uninterruptable flow means that each of these wells is a time bomb, and we seem to be setting those bombs off with disturbing regularity. Twenty years after the devastating spill in Santa Barbara, the Exxon Valdez spill released three times as much crude. Twenty years after the Exxon Valdez, the Gulf spill may have already topped that record on its way to a level of destruction unmatched by any natural disaster.

Should we get away this time without a catastrophe that ruins our southern coast (and the coasts of many other nations) for a generation, we can't forget the lesson that offshore drilling carries an enormous risk. The potential impact of a single well failure is so much greater than anyone anticipated, that further development of this type should not be contemplated unless the need is achingly dire.

And it's not.

As dawn broke Saturday over Venice, many of the oil-cleaning boats began another day tied to the docks. A few fishermen loaded gear and prepared to head to the marshes to try their luck one last time before the water becomes too oily to fish.

::

It's Worse Than You Think

by Devilstower

Sun May 02, 2010 at 06:00:02 AM PDT

It's easy to be pro-drilling. All it requires is a little chanting, a little pretending that somehow this activity can reverse a yawning oil deficit that's been growing since 1970, a little chest-thumping conceit that there's something patriotic or admirable about risking other people's homes, livelihoods, and lives because it pisses off the "tree huggers." All it takes is a little ignorance and a belief that any risk is worth a dime at the pumps. All it takes at turning a blind eye to the real level of danger involved.

Which is going to get a lot harder after this week.

When Deepwater Horizon exploded on April 20, attention was first focused, and quite rightly, on the 11 workers missing, all of whom are now presumed to have died either directly in the massive fireball that engulfed the ship or somewhere in the choppy oil-stained waters. The well they had been working on--which was in the process of being "capped" with concrete when the explosion occurred--wasn't considered a high risk for leakage. The smear of oil on the ocean's surface after the explosion was thought to be mostly from the fuel that had been carried by the drilling ship.

Rear Adm. Landry said no oil appeared to be leaking from a well head at the ocean floor, nor was any leaking at the water's surface. But she said crews were closely monitoring the rig for any more crude that might spill out.

About half a dozen boats were using booms to trap the thin sheen, which extended about seven miles north of the rig site. There was no sign of wildlife being affected; the Louisiana coast is about 50 miles away.

As the search for those missing workers was sadly ended, the slick around the former drill site continued to grow. It was soon clear that the initial hopes that the sinking of the drilling ship and collapse of the well structures would not lead to a prolonged leak were unfounded. What started out as a small slick directly around the drill site enlarged rapidly.

"We thought what we were dealing with as of yesterday was a surface residual [oil] from the mobile offshore drilling unit," Landry said. "In addition to that is oil emanating from the well. It is a big change from yesterday... This is a very serious spill, absolutely."

A robotic camera has determined a pipe leading from the well is leaking oil at an estimated rate of 1,000 barrels--or about 42,000 gallons a day, reports CBS News correspondent Don Teague. That's still much less than the worst-case scenario.

By comparison, Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons in Alaska's Prince William Sound in 1989--the worst oil spill in U.S. history.

That rate was certainly bad enough. The press dutifully reported this number (myself included). But within two days there was evidence that the 1,000 barrels a day didn't match up with the the actual size of the leak.

We have a visible oil slick covering 2,233 square miles (5,783 km2). Given a minimum thickness of 1 micron (see chart below), that is 5,783 cubic meters of oil, or 1,527,706 gallons (36,374 barrels). The blowout happened almost 7 days ago on April 20. That's at least 5,000 barrels of oil per day--assuming none of it was consumed during the two-day fire that raged before the rig sank on April 22, and none has been collected by the response crews that have been working diligently for days.

Government numbers were soon adjusted accordingly--though 5,000 barrels a day was the minimum amount needed to account for the visible slick on the surface. Since then the press has been using that number.

If what's actually been happening is that the well has been releasing around 5,000 barrels a day since the initial explosion, something like 60,000 barrels are now washing around the Gulf. If the well was initially producing less, and the 5k rate kicked in later, the total production should be somewhere between the 12k that would have come from the older 1,000 barrel a day estimate and the 60,000 barrels from the 5k estimate.

If the 5k rate is accurate and the rate of the spillage is steady, the size of the spill will exceed the 1969 disaster in Santa Barbara within the next week. At that rate, it will take another month for the size of the spill to reach that of the Exxon Valdez--though because of the location of this spill, clean up will not only be more difficult, but have far more economic impact than the Prince William Sound spill.

A month may seem like plenty of time to stop the flow, but so far there has been little progress at arresting the spill and BP has appealed to both competitors and the military for new ideas. While there are numerous meetings going on, several ideas have been tossed around, and some actions are underway that may retard the flow there is presently no coherent plan for arresting the spill from the sunken wellhead. Real action to address the problem may take far longer than a month.

But that's not the worst of it. With the estimated rate of spillage having now been adjusted upwards, it's clear that over the last two days the 5k rate is not enough to explain the rapid expansion of the spreading oil slick. It's becoming increasingly obvious that we don't have a month before we reach Valdez levels of disaster.

The surface area of a catastrophic Gulf of Mexico oil spill quickly tripled in size amid growing fears among experts that the slick could become vastly more devastating than it seemed just two days ago. ... The slick nearly tripled in just a day or so, growing from a spill the size of Rhode Island to something closer to the size of Puerto Rico, according to images collected from mostly European satellites and analyzed by the University of Miami.

This may mean that we've simply been underestimating the size of the flow all along, that the 5k scenario undershot the actual leak. But the series of underestimates may have another cause--the size of the spill may have been growing, day by day, right from the start. The source of much of the spilled oil appears to be the damaged valves and piping in a house-sized structure on the sea floor, at a depth of 5,000'. If the openings have gradually been forced wider, the level of flow may soon reach a point where "catastrophic" seems a vast understatement.

Ian R. MacDonald, an oceanography professor at Florida State University, said his examination of Coast Guard charts and satellite images indicated that 8 million to 9 million gallons had already spilled by April 28. ... Alabama's governor said his state was preparing for a worst-case scenario of 150,000 barrels, or more than 6 million gallons per day. At that rate the spill would amount to a Valdez-sized spill every two days, and the situation could last for months.

Increasingly it appears that we are living this "worst case" scenario. If the FSU numbers are correct, we have already reached Exxon Valdez levels of spill, on our way to something much, much worse.

Skytruth, the nonprofit organization that forced both government and industry to admit the 1,000 barrel per day number was way too small has confirmed that Valdez is in the rear view.

Saturday, the group updated its analysis to estimate that the slick contained more than 11.1 million gallons of oil, which would make it the largest oil spill in American history. John Amos, the group's president, also revised the estimate of the rate of oil leaking to 25,000 barrels a day, saying it was a "rock bottom" figure.

You can track Skytruth's estimates and updates at their blog. But note that the 25k number is what would have had to spill from day 1 to match what Skytruth is now seeing on the surface of the Gulf. What's more likely based on the rate of growth seen in the visible slick is that the spill is increasing and is now well past that number.

What we are facing is something far beyond what most people would think possible for the loss of a single well. Something nearly incomprehensible. Should it continue, this will be an oily-Chernobyl for the Gulf of Mexico. Oyster beds that have been sustainably harvested for over 130 years are already being lost. Shrimpers, fishermen, businesses that depend on tourism--all are looking not toward a decline, but an end to these industries that could last for years. The loss of fisheries alone could lead to shortages of sea food worldwide and economic collapse of coastal towns.

The economic damage is only part of it. Wetlands that shelter not just endangered species, but the coasts beyond, could become dead marshes of oil-soaked stumps and the oil-soaked bodies of dead wildlife. Animals that live in the Gulf--from the smallest fish to Sperm Whales--are threatened. Both total population and diversity in and around the Gulf may be impacted for a generation.

Let's hope it doesn't happen (I know what's at the top of my prayer list this Sunday). Let's hope that the worst case turns out to be the "laughably overblown case," that even now the flow of oil is easing, and that within a week some unexpected solution is in place. Let's pray for all of that.

But here's what we shouldn't forget: even if this is solved tomorrow, even if the cause for the explosion is exactly explained, even if what went wrong this time can be safely ruled out from ever happening again, what the sinking of the Deepwater Horizon has demonstrated is that we can't allow offshore drilling to continue. Why? Look at those numbers above. That a single well has the potential to spill millions of gallons in an uninterruptable flow means that each of these wells is a time bomb, and we seem to be setting those bombs off with disturbing regularity. Twenty years after the devastating spill in Santa Barbara, the Exxon Valdez spill released three times as much crude. Twenty years after the Exxon Valdez, the Gulf spill may have already topped that record on its way to a level of destruction unmatched by any natural disaster.

Should we get away this time without a catastrophe that ruins our southern coast (and the coasts of many other nations) for a generation, we can't forget the lesson that offshore drilling carries an enormous risk. The potential impact of a single well failure is so much greater than anyone anticipated, that further development of this type should not be contemplated unless the need is achingly dire.

And it's not.

As dawn broke Saturday over Venice, many of the oil-cleaning boats began another day tied to the docks. A few fishermen loaded gear and prepared to head to the marshes to try their luck one last time before the water becomes too oily to fish.

::