Palace Matinee -- Companions of Fear -- Part 9

Companions of Fear

Part 9

"There was some kind of weird bird singing in the tree outside last night. Even with a few pills on board and some of that whiskey, it kept waking me up," said Darlene as she checked herself in the mirror. She wore an orange cardigan embroidered with green vines and leaves that had once belonged to her grandmother. She picked at a small cigarette burn near its bottom hem.

"That's hot," said Mink from the bed. "You look like an enchanted pumpkin." His left eye was purple and blue and his lip was swollen and split on the right side.

"Fuck you," she said.

"Miss your first class and come back to bed," he said, bleary eyed. "I'm beat up."

"You're just beat."

"Cold, cold heart."

"I can't stiff the class today, I'm gonna lay out the Puritans for them," she said, clipping back her hair. Using her middle finger, she pushed her glasses higher along the bridge of her nose and stepped back.

"Lay me out instead," said Mink.

"You're totally Zwingly but you're no Hutchinson."

She walked over to where he lay and leaned over to give him a kiss.

"Class dismissed," he yelled and grabbed her, pulling her toward the bed. A sharp pain in his ribs interceded, though, that forced him to open his arms and he dropped her. She slid down the side of the mattress onto the floor.

"You're a crazy ass," she said, pulling herself up. She hoisted her jeans with her belt, straightened the legs, touched the hem of the orange cardigan and backed away from him. "Later, loser," she said and blew him a kiss.

"Take those feathers," he called after her.

"I got it," she said as she moved into the living room.

Gage was sprawled out on the old easy chair that Mink had occupied the previous night. The first thing Darlene noticed was that his shoes were off and his feet were propped up on the overturned empty bucket from beneath the kitchen sink. His once white socks were grayer than his complexion, and gave off a scent like expensive cheese. She grimaced as she approached him. Flipping back his jacket, she took one of the three feathers, he'd shown her. As she pulled away from him, his arm shot out and he grabbed the wrist of the hand with the feather. His eyes weren't even open.

"For the bird doctor," she whispered.

He grunted and let her go.

The hallway was filled with the smell of boiling cabbage, but outside it was a cold clear day with a sharp breeze from the north. In the parking lot next to the apartment building, she got into the gold Rustang and started it up. The car ran like a charm. She'd told Mink that even when the body was gone, the engine would run and she'd sit in the driver's seat with nothing between her and the wind. She turned on the radio, the morning back seat oldies show, and put it in gear.

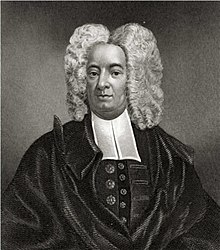

Driving always put Darlene in a daze of deep thinking. She worried about Mink for a while and then switched gears into an idea she had for one of her classes. She'd taken Creative Writing as a way to get easy credits, and it was urgent that she write a story, even a shitty story, so she wouldn't lose those credits. She was reading Cotton Mather for her thesis -- The Wonders of the Invisible World. She couldn't get over the name "Cotton" and she thought of white puffs and rabbit tails, q-tips, the wad in the top of a just opened bottle of aspirin. "What a weird fucking name," she thought. Then she remembered, a novel from her undergraduate class in Urban Fiction by Chester Himes, Cotton Comes to Harlem.

The idea hit her like three Darvon and two shots of tequila. What if Cotton Mather goes to the outhouse one night some time back in 1691, while he was working on Wonders, and by some science fiction bullshit he's transported through Time to the Harlem Renaissance? The idea excited her and she often returned to it. She'd told a guy in her creative writing class about the idea and asked if he thought it was a good one. He told her it was a bad idea for so many reasons and left it at that. He wrote boring stories, though, so she knew it was gold.

The incessant repetition of a doo-wop song on the radio brought her to her senses just in time for her to take her exit. From there it was a quick drive down two city blocks and a straight mile into the country to Craton University. Halfway there, she crossed over the river on a steel bridge and then out at the edge of her sight she could see the spire of the administration building looming over the tree line. The place had been built in the mid-1800's -- stone buildings with turrets, columns out front, unpolished waxed mahogany everywhere inside. The floors creaked. Things were broken. She daydreamed often that the faculty were ghosts.

On her walk from the parking lot to the Science building, she passed along a winding walkway lined on both sides by trees, their yellow leaves scattered on the ground. She went back to thinking about Mink and what a stupid shit he was. Just five years earlier, she'd been mixed up with Chinslow's crowd, snorting lines and drinking, every day three quarters in the bag, getting groped and poked by whoever. She let go of all that, but she couldn't let go of Mink. Or was it that Mink wouldn't let go of her? The only thing she was certain of was that she wouldn't go back. "He's got a clear choice," she said aloud to herself as she reached the bottom steps of Goshen Hall. "Besides," she thought, "he has no idea what a racket academia is."

Goshen, another stone giant, was not as tall as the administration building, but it was vast, with courtyards and hallways that twisted and turned and came to dead ends while others seemed to lead you in a circle. Her one science class, Astronomy, was held there and during that early semester she learned, to an extent, how to navigate the place. There were hallways she never went down, yet always wondered where they led. It had been the residence of Zebedus Goshen, the founder of the school. He'd lived there with his wife, his mistress, and his eight children. The most amusing thing about the place to Darlene was that in the vaulted foyer at the entrance there was hung a thirty foot painting of God, surrounded by billowing clouds, enrobed in blue, an angry face and an accusatory finger. Every time she saw it, she smiled.

She was headed for the main office of the Science Department when she spotted her old Astronomy professor gliding down the hallway toward her. The tails of his white lab coat lifted in the wake of his progress. He had a full head of gray hair and thick gray sideburns, thick glasses and a bottom lip like a sore thumb. She'd always thought of him as a goofball, and she wondered now why he always wore a lab coat when he never did any experiments. All he did was sit in The Hole and stare up at the night sky. The Hole was the university's observatory, a fifty foot concrete lined pit at the bottom of which was a circular bench that went around the inner cylinder. The school couldn't afford a planetarium, so The Hole was the answer. During the class, Darlene and the other students would come to the school at night, descend through the sub-basements of Goshen Hall to a door way, like one to a racquetball court, enter and take their places on the bench. According to professor Beerbauer, The Hole had some effect on the view of the sky above, the clarity of the stars, but Darlene never got it. What she got was an A.

"Darlene," said the professor, not slowing his gait.

"Is there an ornithologist in the Science Department?" she asked.

As he swept by, she saw him put his hand over the pens in his lab coat pocket protector, which she knew meant he was thinking. She stopped and turned to watch him pass. He reached the end of the hallway, but just before he turned, he called back, "Dr. Feens, in the fourth sub-basement, one below the entrance to The Hole. Room X."

She hated the sub-basements -- the long, dimly lit wooden stairways, splintered and cracking, the moldy earth smell. Every time she attended Astronomy, she felt like she was descending into the grave and thought of a line from Emily Dickinson, "The cornice in the ground." There were always noises off in the dark corners of the levels she passed on her way to The Hole. "Next time, Gage can check it out for himself," she thought and just then a figure appeared, ascending out of the shadows of the third sub-basement. A bent old woman, slapping her feet on each step, every breath like it might be her last. Professor Bushard. Darlene knew of her, had seen her before. Supposedly a brilliant theoretical physicist.

"Hello, professor," Darlene said as she moved to the side of the stairs to let the old woman pass.

Bushard looked up at her, eyes blossoming with gray cataracts. She smiled, her teeth, yellow pegs. "Hello, honey," she said. "How's the weather outside?"

"Cool and bright."

"I should make it to the parking lot before the sun goes down."

Darlene moved down into the shadows Bushard had emerged from, contemplating the ancient professor actually driving.

Many of the bulbs that lit the fourth sub-basement had burned out, and it was only by the most meager threads of light that she navigated. There didn't seem to be anything on that level -- no hallways or offices, just a huge expanse of floor, like an empty warehouse. "Fuck this," she thought and was about to turn around and go back when she saw, about fifty yards away, a rectangle of light in the distance. She groped forward.

Stepping through the lit doorway, she was surprised by the contrast of the emptiness outside and the cozy nature of the small office. There was a warm light shining from above, revealing wall to wall shelves of books, a small table with a coffee maker, an old braided rug on the floor, a gold upholstered chair with worn arms from which the stuffing peeked.

She saw that the room she stood in led to another room further back. "Dr. Feens," she called. While she waited for a response, she looked around at the part of the office she was in. For the first time, she noticed that there was a bird cage in the corner, hanging from a tall shepherd's hook affixed to a base on the floor. The little doorway to the cage was open, swinging on tiny hinges. There was a nameplate attached to the bottom rim of the cage, in a fancy script, engraved on a thin silver plaque. It read, MARGY. She wondered if the bird had recently escaped or died, or if this was one of those mind games professors like to play on students. Darlene knew what assholes they could be. She called out his name again but there was no answer.

She walked through into the next room, and there she saw a chubby little man with a bald crown and a wreath of white hair sitting in a chair. His back was to her and he leaned forward as if studying something on the desk or sleeping. He did not wear the indicative white lab coat, but a red plaid shirt.

"Dr. Feens," she said. He never moved, and she guessed he was sleeping. She hated to disturb him, but she'd come down four flights of rickety stairs through the dark, lower than the very Hole, and she wasn't going back until he gave her the time of day. "Dr. Feens," she said, this time leaning closer to his ear. He didn't budge.

"Feens," she said louder. She lightly pushed his shoulder. He felt like a wrapped ham at the butcher counter. "Wake up, Dr. Feens." Instead of merely prodding him, this time she grabbed his shoulder and shook it. Somehow his center of gravity shifted and his body leaned backward in the swivel chair. She leaped away a step. His face was wide as a pillow and pale as snow. The right lens of his glasses was shattered, slivers of glass still on his cheeks, and his eye behind that lens was a bloody burst grape of a mess. A trickle of blood ran from the corner of his gaping mouth. Darlene grunted and shivered. She backed up into a stack of books piled on the floor and toppled it, almost falling, herself. A black bird suddenly flew at her face from the corner of the ceiling, flapping around her eyes, screaming in a human voice, "Repent. Repent."

She was out the office door and across the darkened expanse of the fourth sub-basement in less than twenty seconds. Bounding up the stairs, she kept looking back over her shoulder to see if someone was following her. Passing the third sub-basement she never slowed, even though breathing was becoming a near impossibility. She heaved for air as she pushed on at the same pace. On the way up to the second sub-basement, she pased Professor Bushard, who called after her, "What's it like outside, honey?"