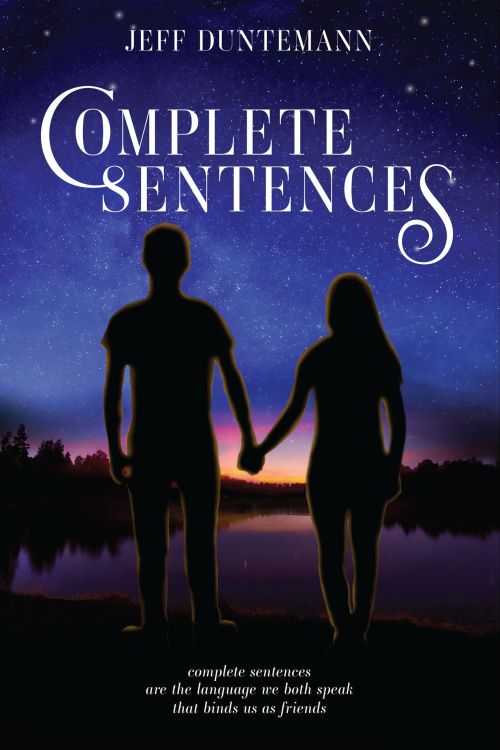

Announcing Complete Sentences

And now for something completely, totally, top-to-bottom (for me at least) different: I present Complete Sentences, a short novel about two very articulate high-IQ 12-year-olds. Not in space. Not in the future. Not on some other planet nor in some unlikely fantasy world. No hyperdrives. No monsters. No magic. Nossir. On Earth, our Earth, our timeline, in Wisconsin. In 1966.

I'm not even sure the term is still used, but when I was first making my name in SF, we called such fiction "mainstream." In other words, a story about ordinary people in the here and (approximately) now, with no fantastic elements at all. Yes, I wrote mainstream fiction. I've done this only one other time in my increasingly long life, back when I was in college in 1972. I wrote a short story about two guys my age who were sweating bullets about the draft lottery during the thick of the Vietnam meatgrinder. My Modern American Literature prof loved it and told me I should try selling it. The story is grim. One guy pulls #244. He's free. The other one pulls #6. He runs. Mainstream literature is full of stuff like that, which is why I now mostly avoid mainstream literature.

So what's it about? Let me borrow the descriptive text I uploaded to Amazon with the book:

It's late summer 1966. Family camping is the rage. Boomer kids are everywhere. Star Trek is brand-new. Smartphones and social media haven't even been dreamt of yet. So summer crushes happen the old-fashioned way: young face to young face.

While scoping out sites for stargazing at Castle Rock Lake, 12-year-old Eric meets a girl from the next campsite over. Charlene and Eric are both gifted, highly articulate kids: Eric in math and science, Charlene in art and composition. He shows her the constellations in the ink-black Wisconsin night sky; she sketches him and writes him poems. An attraction neither has ever felt before soon blossoms between them. Eric's sensible parents caution him that 12 is too young to fall in love, while Charlene's parents barely speak to each other, let alone her. She aches for the love she sees in Eric's family, and takes strength from the attention and kindness that Eric offers her.

For Charlene has a secret, one that cuts to the heart of who and what she is. When the conflict in her family threatens to end the campout early, she must explain that secret to Eric, and begs him to accept the vision she has of her own future. Facing the possibility that they may never see each other again, Eric and Charlene struggle to put words to the feelings that have arisen between them. They discover the answer in the language they both speak, and had spoken together all along: Complete sentences.

I'll post a sample chapter tomorrow.

In the meantime, you all might reasonably ask, Why? For the same reason I wrote whacko humorous fantasy like Ten Gentle Opportunities and Dreamhealer: To prove that I could. Before I wrote Complete Sentences, I didn't know that I could write mainstream fiction. Now I know. Before Kindle made self-publishing possible, I had to write what publishers wanted. I first tasted the forbidden fruit 25+ years ago, when Coriolis established a book publishing operation and I was the one who decided what to publish. Could I have sold The Delphi Programming Explorer to Wiley or Macmillan? That was a gonzo book. It was also the Coriolis book that sold the most copies and pulled in the most revenue for all of 1995. I (maybe barely) sold Assembly Language Step By Step (under its original title Assembly Language from Square One) to the late Scott, Foresman in 1990. That was just as gonzo, if not moreso. (My four-fingered Martians are standing up and cheering.) A guy once sent me an email telling me that that book saved him from flunking out of his computer science program. Yeah, that book is nuts. But I have independent evidence that it works, in the form of hundreds of fan letters. Not to mention the fact that it's been in print now for 31 years.

These days I write what I do largely to push back personal boundaries--and sometimes try things I've been wanting to try for literally decades. I always wanted to write a love story where the nerd gets the girl in the end. It took awhile. Then there was Dreamhealer. I don't call it a love story. But it contains one--in fact, two.

In writing Complete Sentences, I drew on bits and pieces of my own history. (Just bits and pieces. It is pointedly not autobiographical.) When I was 12, I found myself longing for female company. Not love, nor, lord help us, sex. I didn't know why, exactly, but alluvasudden I wanted girls to be my friends. I remember that feeling clearly. I didn't know what to call it, and for the most part it was an annoyance, at least for the next couple of years. I now know what to call it.

Complete Sentences is not a love story, not in the usual sense of the word.

Or...maybe it is.

You tell me.