The Mexican War

Originally published at Leaves of Grass. You can comment here or there.

The Mexican War, though only two years long, weighs heavily among the direct causes of the American Civil War. The new territories won by the United States raised new tensions over the bounds of slavery. The Mexican War also nourished ambitions for a generation of military officers, including West Pointers U.S. Grant and R.E. Lee.

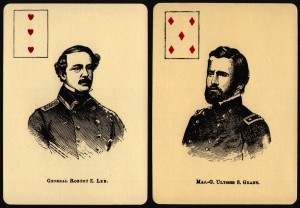

General Lee’s portrait in a deck of Civil War playing cards, captures the continuum of Mexican War to Civil War. The tunic is not true to the Confederate uniform of the Civil War, but is based on a Mexican War period uniform.

When the War broke out in 1846, Mexico had been independent from Spain for 25 years, but had not yet recovered from the collapse of the colonial system. Internal factionalism and social and economic instability weakened her.

The United States, meanwhile, was gripped by the idea of “Manifest Destiny,” a term coined by journalist John L. O’Sullivan. Manifest Destiny held that the American people had a sacred duty to redeem the rest of the continent with the spread of democracy and virtue. The belief had its sincere adherents, including Walt Whitman, but for many it cloaked a hunger for land - and for a coast-to-coast slave market. James K. Polk, U.S. president from 1845 to 1849, believed completely and aggressively in Manifest Destiny, and that included taking Mexican territory.

The pretext for war with Mexico was easy enough to come by. Mexico did not recognize the 1845 annexation of Texas to the United States, and the subsequent U.S. military presence along the Rio Grande kindled animosity. President Polk pushed Mexico not only to recognize Texas as part of the United States, but also to sell lower California. He pushed hard, and to his surprise Mexico pushed back. The two nations went to war.

Although Manifest Destiny is often presented as a sentiment held uniformly by the people of the United States, many citizens were indifferent if not outright hostile to expansion and considered the war on Mexico an outrage. “For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the [annexation of Texas],” said U.S. Grant in his memoirs, “and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory.” Grant, at least in hindsight, considered “the occupation, separation and annexation [of Texas], from the inception of the movement to its final consummation, a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.”

Walt Whitman opposed slavery, but he not only fiercely supported war with Mexico, he advocated the annexation of “the main bulk of that republic.” Disclaiming a “lust of power and territory,” his opinion is a textbook illustration of Manifest Destiny: “We pant to see our country and its rule far-reaching, only inasmuch as it will take off the shackles that prevent men the even chance of being happy and good….” (Years later, during the American Civil War, Whitman thought differently. On pondering what he considered “the united wish of all the nations of the world that [the United States’] union should be broken,” he reflected “Mexico, the only one to whom we have ever really done wrong, [is] now the only one who prays for us and for our triumph, with genuine prayer.”)

The United States won the Mexican War, gaining what would later be nearly all of the states of Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah, and parts of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. The United States - the southern United States - now reached from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The new acquisitions rocked the already uneasy and forced balance of slave and free states and territories.

Victory left some of its winners floundering. Ulysses S. Grant resigned from the army a few years later, only to fail at one business venture after another, including farming his in-laws’ property with the use of slave labor. Robert E. Lee stayed in - the alternative was to be a plantation master at his wife’s ancestral property, Arlington, a role that he detested - but he chafed at military assignments that offered little hope of promotion.

The Civil War revived ambition and gave it scope. Mexican War veterans who achieved fame and the rank of general in the Civil War include Confederates P.G.T. Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Albert Sidney Johnston, Joseph E. Johnston, James Longstreet, George Picket, and Edmund Kirby Smith; and Federals John C. Frémont, Joe Hooker, George McClellan, George Meade, Winfield Scott, and William Tecumseh Sherman.

Generals R.E. Lee and U.S. Grant first met each other not on a Civil War battlefield, but in Mexico, as Grant famously recalled when they met again at Appomattox, Virginia. Peace would never have advanced these men to the prominence they achieved in the Civil War.

Grant, U.S., Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.” Whitman, Walt, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 11 and June 6, 1846, via nationalhumanitiescenter.org. “Attitude of Foreign Governments during the War,” in Specimen Days, via The Walt Whitman Archive