meta: The Secret of Alchemy -- Crimson Horror

Doctor Who meta: The Crimson Horror

spoilers through the episode

Alchemy, The Hero's Journey, and Narrative Compression

This episode is so dense, so laden with imagery and themes and good meta stuff! It's taken me a while to process it -- in fact, I'm still processing. But it's also been one of those weeks, just having a hard time concentrating, and this was a story that required more research on my part than I'm accustomed. I would have gotten this up yesterday, but I was found by a bottle of Chianti and passed out before I could really get started. Today, however, I awoke fresh and alert, so here we are, better late than never!

The Secret to Alchemy

There are two refreshments in your world the color of red wine. This is not red wine.

DOCTOR: Planning a little fireworks party, are we?

GILLYFLOWER: You have forced me to advance the Great Work somewhat, Doctor,

but my colossal scheme remains as it was. My rocket will explode high in the atmosphere,

raining down Mister Sweet's beneficence onto all humanity.

CLARA: And wiping us all out. You can't!

GILLYFLOWER: My new Adam and Eves will sleep for but a few months before stepping out

into a Golden Dawn. Is it not beautiful, Doctor?

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was a western occult group of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Founded by Rosicrucian Freemasons, it was an "alchemical" group devoted to spiritual development through study and ritual. From this center came the likes of Aleister Crowley and Dion Fortune, not to mention the development of the most popular Tarot deck, the Rider-Waite, illustrated by Golden Dawn member Pamela Coleman Smith.

So what is this alchemy business, and what does it have to do with The Crimson Horror?

The essence of alchemical teaching lies in metaphor. The processes of chemistry -- the mixing of substance to produce something new -- is likened to the spiritual work of knowing thyself. Which is to say, a way of looking in a mirror such that one's "true will" is revealed. You can think of this "true will" as the inner workings of the subconscious mind, which can only be fully revealed upon the death of the conscious mind -- the Ego -- but the part of the subconscious that's not the Id (the Monster) but the Superego (the Divine.)

There are three substances crucial to The Great Work: Sulphur, Mercury, and Salt.

Sulphur is the Active principle, associated with Fire, the spirit, the sun, the lion. Mercuy -- quicksilver -- is the Celestial Water, the receptive soul, the moon. Salt is the crystallization of the process, what emerges from the union of opposites. It is a form of embodiment, the divine made manifest.

The crucible of Sulphur (the Lion) and Mercury (the Silver) yields the Salt.

Quote:

In alchemy it is declared that without putrefaction the Great Work cannot be accomplished. What is it that dies on the cross, is buried in the tomb of the Mysteries, and that dies also in the retort and becomes black with putrefaction? Also, what is it that does this same thing in the nature of man, that he may rise again, phœnix-like, from his own ashes (caput mortuum)?

The solution in the alchemical retort, if digested a certain length of time, will turn into a red elixir, which is called the universal medicine. It resembles a fiery water and is luminous in the dark.

-- "The Secret Teachings of all Ages," by Manly P. Hall

The are three stages to The Great Work (or four, depending on your school.) The first stage is called nigredo, and it's represented metaphorically by the blackening of the elements of Sulphur, Mercury, and Salt, which represent the individual. In the Crimson Horror, this stage is shown by the Pilgrims, who all wear black. Notice the Dark Red Flowers over their hearts.

EDMUND: All will be well, but we must get to the bottom of this dark and queer business

no matter what the cost.

GILLYFLOWER: The bright day is done, child, and you are for the dark.

VASTRA: If our stratagem succeeds, Jenny will infiltrate deep into the black heart of this curious place.

ADA: She does not want me, monster. I am not to be chosen. Perhaps it was my own sin,

the blackness in my heart that my Father saw in me.

The point of this stage in The Great Work is to recognize the fact we live in ignorance, in the dark; that we have base desires and a shadow within our souls; and that Death awaits us all, with Decay or "putrefaction." The Pilgrims are the one who bring such tidings to our heroes by force, by violence. They surround Effie after her husband goes to investigate, they do the work of loading up the rocket with venom, they capture the Doctor and Clara.

However, our heroes in the Paternoster Gang all partake of the Dark. The Dark isn't inherently evil or good, it simply is. So Vastra wears the black veil, a symbol of the material veil that covers our eyes from the truth of Divinity. Strax wears the black butler's suit, a symbol of Service to each other. Jenny's a martial arts expert, and she throws off her earth-toned cloak to reveal a black outfit of leather and burnout velvet before engaging in violence.

The second stage of the Great Work is called albedo. This is the stage of purification, where the darkness of the soul is stripped away. It's represented by the white undergarments of the Sweetville captives.

Clara's perfect for representing this, simply by virtue of her name.

It corresponds to what in alchemy is called The White Elixir, which turns base metals into Silver. Now, silver is the metal of mirrors, and it's the ability to reflect both internally (know thyself) or externally. It's the Hermetic principle, in honor of Mercury. It's also likened to The Divine Feminine, in the passive aspect -- and yes, this is a problematic construction, but it's important to remember that everyone partakes of both sides of every duality.

The final stage is called rubedo, the Reddening. If the White Elixir turns base metals to Silver, the Red Elixir can turn base metals to Gold -- in alchemy, "gold" was associated with "redness." (There's often an intermediate stage called citrinitas or xanthosis, the "yellowing," but for our purposes we're treating it as part and parcel of the rubedo, because they're so similar.)

The stage of rubedo signifies the completion of The Great Work, which is the completion of the Self. All polarities have been unified, and the True Self is revealed.

The Mystery of Alchemy cannot be understood or practiced except through metaphor, which is a form of magic. When taken literally, we get "chemistry" and the impossible task of turning actual lead into actual gold for the gratification of only the ego; this is as far from The Great Work as we can get. Above, we see the Doctor revealed as a Monster, but this a reflection of the corruption of Gillyflower's alchemy, which has been literalized, and which is focused solely on the material components of perfection.

However, we have plenty of other examples of The Reddening, thanks to director Saul Metzstein's impeccable use of light in this episode:

Jenny is one of our heroes from the Paternoster Gang.

Here she's snuck into the underbelly of Sweetville, and we

see she's completely in her element. Jenny's true self is

revealed as a Hero, as someone versed in the art of

discovery, of uncovering the truth.

Ada's reddening occurs at the end of the story. Here she's

finally ready to let go of being in the stage of perpetual purity

(the albedo dress) -- and she's accepted that part of her

which is her mother. She refuses to grant forgiveness, and

destroys Mr. Sweet in a justified rage for all the torment

visited upon her by the intervention of the repulsive red

leech.

Gillyflower's deathbed. She's fallen from the Great Work,

and Mr. Sweet abandons her; she realizes the truth that she

was never a partner, only a host. She is gratified, however,

that her daughter has learned an important truth from the

mother.

Clara awakens from her torpor, another version of perpetual

albedo. Her time under glass (glass is a reflective surface)

in a state of perfect passivity had rendered her "frozen in

time." Remember, Gillyflower's alchemy had that effect on

the Doctor, making him a "stiff." True rubedo is achieved

through proper alchemy, by balancing polarity: Clara

awakens in a Steam Cupboard, where Steam is a fusion of

Fire and Water.

To sum up, The Crimson Horror works with these basic alchemical principles mis-applied. The Red Elixir that creates perfection is used only for the base material of the body -- itself a "crimson horror" of blood and flesh and gristle, which will inevitably putrify. Gillyflower seeks perfection of the body, as if this kind of preservation will confer "eternity." But really, she desires immortality; the wise know that eternity is found in the Here and Now.

So, here are a couple other shots that demonstrate the Triune Alcemy:

Here we have Strax in Black, Vastra in a shimmering

mercurial dress, and the Red Elixir between them. Strax is

male, Vastra is female. Both are Monsters, but they take on

human roles; both are "covered." They are joined together

by the Red.

Gillyflower's Organ -- Music is what brings everything

together. To the left, an hourglass -- the Salt, and the

symbol of Death and Decay. In the middle, a Mirror --

silvery, mercurial, receptive. To the right, a Golden Snake --

the base metal turned to gold, the active principle and

suggestive of the venom behind Mr Sweet's kiss.

For those who are interested, we've had this kind of Alchemical storytelling in Who before, and in the magical literary traditions outside of our own little corner of the universe.

So, let's go back to the other Gatiss story this year, Cold War. In the climax to that story, the Doctor confronts Skaldak with the Red Setting on his Sonic; the Doctor is more than willing to sacrifice himself in an act of mutually assured destruction to prevent nuclear war. But it seems that Clara's invocation of the "Songs of the Red Snow" that truly gets the Ice Warrior to chill -- and no wonder, for "the Red Snow" is a much more alchemical mixture, having both the Red Elixir of self-sacrifice and the White Elixir of empathy to draw on -- Clara can empathize because she's a "lost daughter" with a mother, and Skaldak's a "lost father" without a daughter.

And yes, this entirely forms the construction President Snow in the Hunger Games trilogy. Birds on fire, the girl on fire, the Fire Woman! Book One rooted in the Black Coal of District 12, Book Two featuring so much Snow, and Book Three culmanating with a "rose" on Fire.

Or look at Harry Potter's best friends. Hermione -- she's the Hermetic one, cool and reflective, a female Hermes. Ron, on the other hand, is the hothead with the Red Hair. They are the crucible who together give Harry the space to effect his own transformation.

This stuff is everywhere.

The Heroic JourneyQuote:

Now the Great Work is the redemption of spirit from matter; that is, the establishment of the kingdom of God. Jesus being asked when the kingdom of God should come, answered, "When Two shall be as One, and that which is Without as that which is Within."

In saying this, he expressed the nature of the Great Work. The Two are spirit and matter: the within is the real invisible; the without is the illusory visible. The kingdom of God shall come when spirit and matter shall be one substance, and the phenomenal shall be absorbed into the real.

-- "Clothed with the Sun," by Anna Kingsford

Yesterday the absolutely marvelous lonewytch wrote of The Heroic Journey in her wonderful Crimson Horror meta, The Bell Jar. She saved me a lot of writing (Eyes, Chair Agenda, Literature!) but I have one quibble, which is on the subject of the Heroic Journey. This episode isn't a pause -- rather, it's a subversion or a retconning of the heroic stage knowne as Atonement With The Father, which Joseph Campbell was fond of punning as "at-one-ment" with the father.

As is the case with Alchemy, the Heroic Journey is a metaphor for spiritual development. Campbell positions it as a treatise on the mythologies of the world, as a work of literary analysis, but this is about as helpful as saying that Alchemy is the study of chemistry. Taking Campbell literally is just as problematic. There's a lot more to mythology than the Heroic Journey, and taking the Journey as an exercise in academic scholarship misses the point.

Furthermore, the Journey has had an unfortunate effect on Hollywood, where the various stages of the Journey are taken as bullet points in by-the-numbers storytelling. It's doubly problematic that the stages are presented so literally -- lots of Daddy Issues, women as shapeshifters and temptresses, lots of Reluctant Heroes. It makes our stories very predictable, and misses the underlying points of so many stages, like what the metaphor of the Father points to -- our issues with Power and the mystery of Consciousness in the flesh.

I think it's fine to use the Heroic Journey as a developmental structure for a series, a character arc, an episode, as long as it's using the material innovatively, and getting to the underlying heart of what the various stages are really about.

First, while The Crimson Horror doesn't actually feature any Fathers or Gods, we do get plenty of associations that make it easier to see what this story is getting at.

Gillyflower pulls back her robes to reveal Mr. Sweet suckling at her heart, a dark mirror of the familiar iconography of the Sacred Heart of Christ, but with a False God where compassion should reside. (This, by the way, is where the Rosicrucians appropriate some of their imagery, but with a mind to balance polarities they put the Rose at the center of the Cross, combining female and male referents.)

At the dinner table, where we first get a clue to who Mr. Sweet is, we're offered this image:

An empty Red Chair, fit for a king, and haloed by a love seat behind it. This, by the way, is a metaphor for God -- there's an absence, or better yet an invisibility. And the neat thing about this image is that works regardless of whether one's a believer or an atheist -- either the God is absent in the way of a Mystery, because God is behind the Veil of reality, or the chair is empty because there's no god at all.

The Paternoster Gang is named for the "Our Father" prayer; the Latin wording obscures the meaning. Artie and Angie try to blackmail Clara by threatening to reveal her secrets to their father. Gillyflower claims that Ada's blindness is caused by her father's "drunken rage." Gillyflower's "chimney tower" with the Rocket housed within are both great phallic symbols, but they offer a False Ascension.

So, the absent father, but also a lot of veils, curtains, coverings that pulled away in the name of a Reveal.

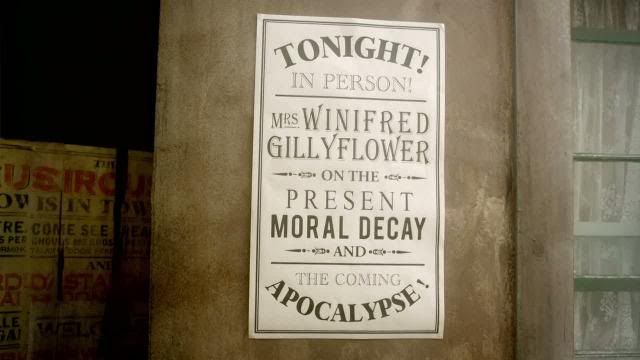

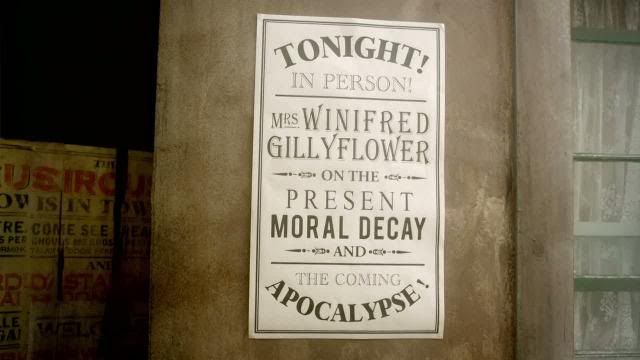

The word "apocalypse" is often meant to refer to The End of the World (heh, Rose in the Cross back in Series 1) but the etymology of the word actually refers to the Reveal, to an uncovering of a hidden earth-shattering truth. This Reveal is a promise of Alchemy, a promise that the unification of one's dualities will bring about an insight of one's True Self.

Crimson Veils are used to set up Reveals at Gillyflower's "apocalypse" talk. On the one hand we have Ada, living proof of the decay of the mortal body, yet someone who's blindness allows her to see more in people than the flesh covering. Ada's in a Circle, the Divine Feminine, with her mercurial outfit and albedo eyes.

Under the Square we have Sweetville, which is the alternative to Death and Decay -- it's a permanent state of preservation. Being frozen solid. A perversion of the Divine Masculine. And notice how the Circle and the Square are separate, cleaved apart; this is the antithesis of The Great Work.

We even get a Library reference -- people will line up to put their names in the Book of Life to the right.

There's a tremendous amount of fakery in this episode. Fake noise in a fake mill. The fake organ is actually a rocket console. The chimney is a fake, offering a fake ascension. The fake science of the Optogram. Gillyflower fakes spilling the salt, in order to feed Mr. Sweet. Edmund and Effie at the beginning, they were fakes, journalists who infiltrated Sweetville in order to discover its secrets.

Jenny, Clara, and the Doctor all fake their way into Sweetville, for that matter. And Jenny gets another woman to fake a fainting spell! So, yes, fake people. Which means we have fake monsters.

Take Strax. He's a Sontaran warrior. He recommends all kinds of creative violence, yet he makes friends with a smart little boy. He's not a monster, he's played for laughs. He's also someone who wears a costume, pretending to be a Victorian butler, well, except that he is a man of service. But this outfit is ultimately just a robe, a curtain, a veneer.

Vastra's another veiled monster, literally. The lace veil covers her monstrosity, her cold-bloodedness, and though she's strictly The Veiled Detective in this story, we see she's got another warrior side to her as well in A Good Man and Snowmen, especially when she takes the role of Doctor's Companion. The same goes for Jenny, who throws off the cloak of Victorian airs to break out some ninja moves.

The Doctor is a fake monster, and Clara's become like a barbie doll, and they both pretend to be people other than they are; they frequently embody a revelry in genuine inauthenticity.

But there is a character who isn't a fake. She's the one who ascends the Spiral Staircase up to the Doctor's lair, a nice allusion to the imagery of The Snowmen:

Ada is utterly authentic. She speaks her mind (the Red Hair is her active principle) and by virtue of being blind is not prone to judge people by what they're wearing -- whether cloaks of linen or cloaks of life, flesh and blood. Because she never pretends, she is always seen -- though obviously being seen in no way guarantees a compassionate reception, as her relationship to her mother attests.

"Ada" is an interesting name, with multiple referents. The German etymology suggests "nobility" -- and it's true, Ada carries herself as a noblewoman. (And, funny enough, one of the brick-wall posters names Donna!)

But the Hebrew etymology prefers "adornment." And I find that much more interesting, given the curtain/veneer themes of this episode. Plus, it ties into Nabokov's Ada, which concerns itself with twinned realities and the texture of time. "The Past, then, is a constant accumulation of images. It can be easily contemplated and listened to, tested and tasted at random, so that it ceases to mean the orderly alternation of linked events that it does in the large theoretical sense. It is now a generous chaos," says Nabokov, who investigates "its veily substance, with illustrative metaphors gradually increasing, very gradually building up a logical love story, going from past to present, blossoming as a concrete story, and just as gradually reversing analogies and disintegrating again into bland abstraction."

"I wonder," said Ada, "I wonder if the attempt to discover those things is worth the stained glass.

We can know the time, we can know a time. We can never know Time. Our senses are simply

not meant to perceive it. It is like--"

I'm also reminded of Alice in Wonderland, visiting the Pool of Tears: "Dear, dear, how queer everything is today! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next great question is 'Who in the world am I?' Ah, That's the great puzzle!" And she began thinking over all the children she knew, that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them. "I'm sure I'm not Ada," she said, "for her hair goes in such ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all..."

Ada is able to "see" past the Doctor's monstrosity -- not that she's blind to him being a monster, but that being a monster doesn't necessarily mean the person inside is a monster. And it's with a monster that she practices secrecy, the most honest form of fakery -- but even here, being with the monster is a way for her to be authentic. And, perhaps, to be appreciated.

Which brings me to the other side of honesty:

The Coroner. I don't think he's faking his relish for the grisly side of nature, even though he keeps such artifacts behind a curtain of his own.

To be at one with the Father, one must abandon the flesh and identify with the spirit within, and yet one must also realize that the Flesh and Spirit are One; the opposites must be conjoined. Our flesh is that "crimson horror," the cloak of life we wear to be in this world, a cloak that will eventually become threadbare and moth-eaten. We are and are not our appearances -- for everything that partakes of Being partakes of Appearance, and yet these are not the same.

It's a paradox, and a Mystery, and that, I think, is the essence of Atonement With The Father, not faffing about in Daddy Issues.

Narrative CompressionQuote:

Some must needs be satisfied first intellectually. These are regenerate first in the mind; and afterwards they attain to the kingdom.

But some begin from within; and these are the most blessed. For they seek the kingdom first, and the rest is added to them afterwards. These last begin the Great Work in the heart, by means of the affection. And the grace of love attracts the Holy Spirit, and transmutes them from glory to glory, so that the reason, or mind, is suddenly enlightened by the inner reason; and with such the work of regeneration is instantaneous--"in the twinkling of an eye."

-- "Clothed with the Sun," by Anna Kingsford

Me, I happen to like the kind of compression that's used these days to tell Doctor Who stories. Everything's so densely packed I can always find more over several viewings -- but then, I anticipate watching every new story several times. I look forward to watching every new episode several times! I don't watch, say, Game of Thrones in the same manner. I only need or care to see an episode of that once, in general, certain scenes excepting. Same goes for just about everything else I watch.

So, let's talk about story compression for a bit, because I think this *is* an issue in Doctor Who these days -- hell, it came up at an academic symposium on the show at DePaul University last weekend, though sadly there wasn't any time to actually, you know, explore it.

First off, it's not just Doctor Who. All television has embraced compression to some extent. None as much as Who, but then Who is doing things that no other show on TV can pull off right now.

In fact, compression is at the heart of filmmaking -- it's inherent in the cut. So we already know how to stitch stories together. And because we've seen so many stories, and understand all the accreted conventions of televisuals so well, we not only fill in the narrative gaps produced by editing, we fill in those gaps with amazing detail based on the particular kinds of tropes and references the work employed.

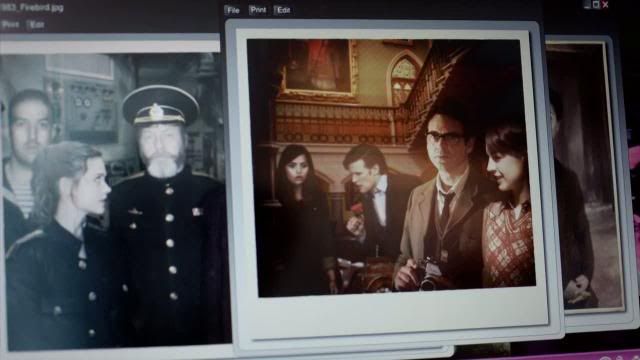

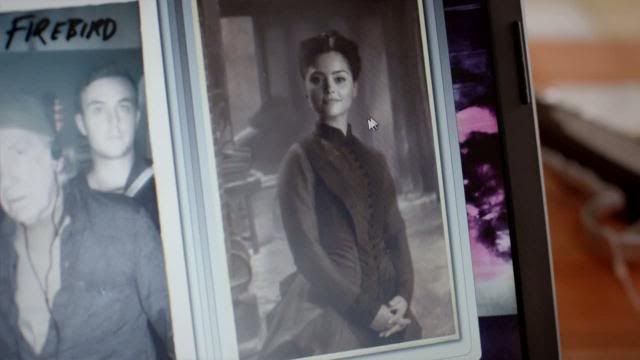

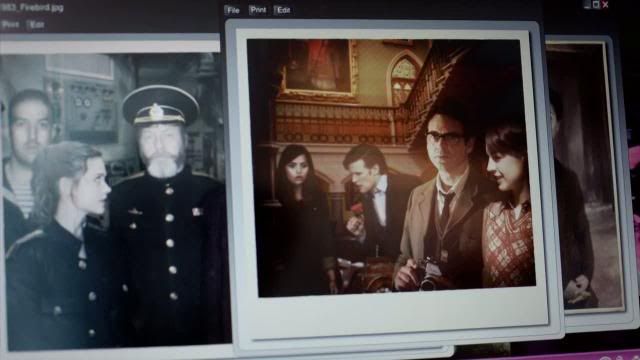

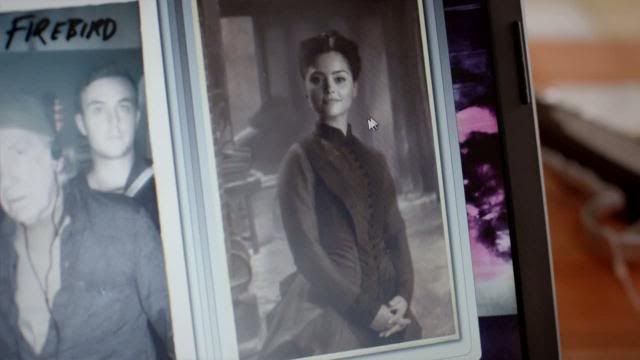

Doctor Who is a particularly visual show, more visual than anything else on TV right now. It's loaded with imagery, and importantly, it's loaded with recurring imagery. The meanings of those images accumulate over time. Interestingly, the FlashBack sequence plays on this by using static images, flashes before our eyes, with a veneer of old-time photography/filmmaking informing the aesthetic. Just a few choice scenes are all we need to get the plot, while the aesthetics of the sequence provide all we need to know about setting and mood and feel.

Here's the thing: we just had an episode a couple weeks ago that played with photography. The Doctor went back in time and took photos throughout the gazillion years of Earth's history to tell the story of someone who's nearly frozen in place. Last week, we entered the Heart of the TARDIS, which was frozen in time. And this week, we see the Doctor stiff as a board in crimson, and Clara practically petrified under glass -- and photographs are used to help unravel the mystery, which is what we get at the beginning of the story.

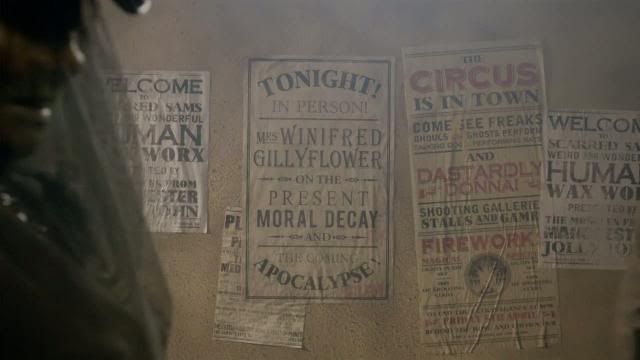

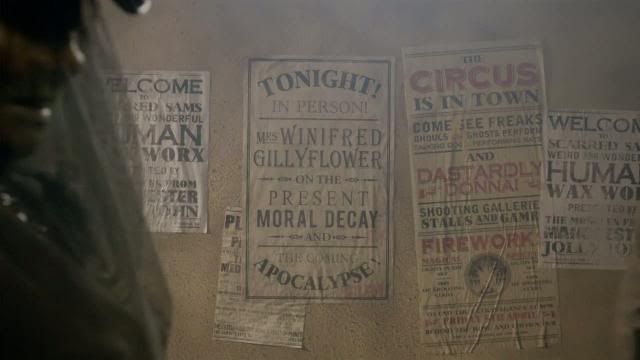

For example, on the wall behind Strax and Vastra, we see a bunch of posters, still images, and they all have clues regarding the story. The Apocalypse and Gilliflower. "Come see the Freaks," another posters announces; Gilliflower calls our heroes "freaks" at the end. "Shooting Galleries" and "Fireworks," both present in the climax. "Human Wax Works," pointing to Clara under the Bell Jar. They're even prophetic -- the Circus in reference to the Nightmare Fair of next week's previews, a suggestion that Donna might be returning, and at the bottom another pointer to The Rose and Crown where Clara used to work.

So we are overloaded with images, and have to actively engage with the text in order to "put it all together." Obviously, this goes against the grain of passive viewing, and even begs for something resembling "work" on the part of the viewer, but on the other hand it provides a distinctly immersive environment -- because we have to do what the heroes of the story have to do in order to resolve the story, and to make sense of the mystery.

I have no doubt this is absolutely intentional.

So, thinking about the current trend in Who, if we hadn't had the hook-end to Crimson Horror, would that have changed the aesthetic considerations of the story? I think not. Given an extra two or three minutes of running time, we would have gotten an extra two or three minutes of highly compressed storytelling. That aesthetic and discourse have already been chosen, comprising the weft of the narrative structure -- making us the weft of the narrative structure.

In fact, this is exactly what the children do in the hook-end. They have constructed the entire narrative of Clara's season from a few select images, and in so doing they have put themselves into the story itself. Which is what compressed storytelling asks us to do. The final scene is a great example of this.

We've seen Clara go home after an adventure before -- twice before, actually. So this particular action has already been established within the show's narrative conventions as something that happens. The surprise here isn't that she's home, it's more of a "oh, we haven't seen Clara do this in a few weeks." It isn't out of nowhere.

There's a "bridge" between this scene and the end of the "proper story": We get repeated dialogue of "the boss" from the previous scene -- we can infer that they've come straight from Victorian Yorkshire, and we haven't missed any important story beats. There's also the musical score tying the two scenes together -- not incidentally, the score is Clara's Theme, orienting us to her character; remember, the last beat in Yorkshire is the Doctor blowing off Jenny's request for an explanation of Clara.

We see Clara sneak into the house and check herself out in the mirror; she's changed her clothes. It's coupled with the shot of the TARDIS disappearing on the security camera, an effective invocation of The Bells of Saint John, which was all about the Doctor finding Clara and convincing her to travel with him; with two repeated shots, we're back into the long arc of the story. In Doctor Who, many of the scenes that serve to remind us of the Long Arc bookend an episode.

So we get a scene that mirrors action from several previous episodes, and that literally shows us the kind of "reading" the show expects of its viewers -- the "implied reader" is the construct of every author, the imagined audience for whom we write. Doctor Who is written with savvy kids in mind, and it's very self-aware of the narrative conventions it employs while doing so. This is a mark of good writing.

The other thing this scene accomplishes is to highlight Clara's internal conflict, and where that conflict mirrors the Doctor's own issues. She's presented with a choice: let the kids "in on it" or risk losing this particular familial relationship -- for the kids have tangible narrative evidence, and trying to explain that evidence to the father will be problematic; even if he doesn't believe them, he might decide it's time for Clara to go.

The photo from Snowmen highlights that as she's been hiding a true part of herself from this family, so too has the Doctor been keeping secrets from her; one one fell swoop, she reveals the secret of her time-traveling ("No, I was in Victorian Yorkshire") to the kids, just as the Doctor's secret is revealed to her. The cat's out of the bag for all parties concerned.

Any time we get into character motivation and internal conflict, we have good writing. The choice Clara faces is between her need for travel and her need for family -- and her alchemical solution will be to travel with family. The Doctor needs his privacy, needs companionship, needs "to solve the mystery" -- his alchemical solution has been to travel with the mystery while keeping secrets from her, and now this choice has been taken away from him, he's gonna have to fess up, something he doesn't like to do... and we like seeing characters having to do things they don't like to do, because so much of our own lives are about doing things we don't like to do. It gets to the heart of our own internal conflicts.

In short, the current style of Doctor Who begs for a close reading, and the text itself (which now engages in the "screencapping" of close readers) confirms that the "leap of faith" required to interpret the barrage of images will, as it does for Artie and Angie, confer the ability to travel with the Doctor, in all of Time and Space.

This too, of course, is a metaphor. Angie's jumper suggests what the metaphor is actually about:

As always, thanks for reading!

spoilers through the episode

Alchemy, The Hero's Journey, and Narrative Compression

This episode is so dense, so laden with imagery and themes and good meta stuff! It's taken me a while to process it -- in fact, I'm still processing. But it's also been one of those weeks, just having a hard time concentrating, and this was a story that required more research on my part than I'm accustomed. I would have gotten this up yesterday, but I was found by a bottle of Chianti and passed out before I could really get started. Today, however, I awoke fresh and alert, so here we are, better late than never!

The Secret to Alchemy

There are two refreshments in your world the color of red wine. This is not red wine.

DOCTOR: Planning a little fireworks party, are we?

GILLYFLOWER: You have forced me to advance the Great Work somewhat, Doctor,

but my colossal scheme remains as it was. My rocket will explode high in the atmosphere,

raining down Mister Sweet's beneficence onto all humanity.

CLARA: And wiping us all out. You can't!

GILLYFLOWER: My new Adam and Eves will sleep for but a few months before stepping out

into a Golden Dawn. Is it not beautiful, Doctor?

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was a western occult group of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Founded by Rosicrucian Freemasons, it was an "alchemical" group devoted to spiritual development through study and ritual. From this center came the likes of Aleister Crowley and Dion Fortune, not to mention the development of the most popular Tarot deck, the Rider-Waite, illustrated by Golden Dawn member Pamela Coleman Smith.

So what is this alchemy business, and what does it have to do with The Crimson Horror?

The essence of alchemical teaching lies in metaphor. The processes of chemistry -- the mixing of substance to produce something new -- is likened to the spiritual work of knowing thyself. Which is to say, a way of looking in a mirror such that one's "true will" is revealed. You can think of this "true will" as the inner workings of the subconscious mind, which can only be fully revealed upon the death of the conscious mind -- the Ego -- but the part of the subconscious that's not the Id (the Monster) but the Superego (the Divine.)

There are three substances crucial to The Great Work: Sulphur, Mercury, and Salt.

Sulphur is the Active principle, associated with Fire, the spirit, the sun, the lion. Mercuy -- quicksilver -- is the Celestial Water, the receptive soul, the moon. Salt is the crystallization of the process, what emerges from the union of opposites. It is a form of embodiment, the divine made manifest.

The crucible of Sulphur (the Lion) and Mercury (the Silver) yields the Salt.

Quote:

In alchemy it is declared that without putrefaction the Great Work cannot be accomplished. What is it that dies on the cross, is buried in the tomb of the Mysteries, and that dies also in the retort and becomes black with putrefaction? Also, what is it that does this same thing in the nature of man, that he may rise again, phœnix-like, from his own ashes (caput mortuum)?

The solution in the alchemical retort, if digested a certain length of time, will turn into a red elixir, which is called the universal medicine. It resembles a fiery water and is luminous in the dark.

-- "The Secret Teachings of all Ages," by Manly P. Hall

The are three stages to The Great Work (or four, depending on your school.) The first stage is called nigredo, and it's represented metaphorically by the blackening of the elements of Sulphur, Mercury, and Salt, which represent the individual. In the Crimson Horror, this stage is shown by the Pilgrims, who all wear black. Notice the Dark Red Flowers over their hearts.

EDMUND: All will be well, but we must get to the bottom of this dark and queer business

no matter what the cost.

GILLYFLOWER: The bright day is done, child, and you are for the dark.

VASTRA: If our stratagem succeeds, Jenny will infiltrate deep into the black heart of this curious place.

ADA: She does not want me, monster. I am not to be chosen. Perhaps it was my own sin,

the blackness in my heart that my Father saw in me.

The point of this stage in The Great Work is to recognize the fact we live in ignorance, in the dark; that we have base desires and a shadow within our souls; and that Death awaits us all, with Decay or "putrefaction." The Pilgrims are the one who bring such tidings to our heroes by force, by violence. They surround Effie after her husband goes to investigate, they do the work of loading up the rocket with venom, they capture the Doctor and Clara.

However, our heroes in the Paternoster Gang all partake of the Dark. The Dark isn't inherently evil or good, it simply is. So Vastra wears the black veil, a symbol of the material veil that covers our eyes from the truth of Divinity. Strax wears the black butler's suit, a symbol of Service to each other. Jenny's a martial arts expert, and she throws off her earth-toned cloak to reveal a black outfit of leather and burnout velvet before engaging in violence.

The second stage of the Great Work is called albedo. This is the stage of purification, where the darkness of the soul is stripped away. It's represented by the white undergarments of the Sweetville captives.

Clara's perfect for representing this, simply by virtue of her name.

It corresponds to what in alchemy is called The White Elixir, which turns base metals into Silver. Now, silver is the metal of mirrors, and it's the ability to reflect both internally (know thyself) or externally. It's the Hermetic principle, in honor of Mercury. It's also likened to The Divine Feminine, in the passive aspect -- and yes, this is a problematic construction, but it's important to remember that everyone partakes of both sides of every duality.

The final stage is called rubedo, the Reddening. If the White Elixir turns base metals to Silver, the Red Elixir can turn base metals to Gold -- in alchemy, "gold" was associated with "redness." (There's often an intermediate stage called citrinitas or xanthosis, the "yellowing," but for our purposes we're treating it as part and parcel of the rubedo, because they're so similar.)

The stage of rubedo signifies the completion of The Great Work, which is the completion of the Self. All polarities have been unified, and the True Self is revealed.

The Mystery of Alchemy cannot be understood or practiced except through metaphor, which is a form of magic. When taken literally, we get "chemistry" and the impossible task of turning actual lead into actual gold for the gratification of only the ego; this is as far from The Great Work as we can get. Above, we see the Doctor revealed as a Monster, but this a reflection of the corruption of Gillyflower's alchemy, which has been literalized, and which is focused solely on the material components of perfection.

However, we have plenty of other examples of The Reddening, thanks to director Saul Metzstein's impeccable use of light in this episode:

Jenny is one of our heroes from the Paternoster Gang.

Here she's snuck into the underbelly of Sweetville, and we

see she's completely in her element. Jenny's true self is

revealed as a Hero, as someone versed in the art of

discovery, of uncovering the truth.

Ada's reddening occurs at the end of the story. Here she's

finally ready to let go of being in the stage of perpetual purity

(the albedo dress) -- and she's accepted that part of her

which is her mother. She refuses to grant forgiveness, and

destroys Mr. Sweet in a justified rage for all the torment

visited upon her by the intervention of the repulsive red

leech.

Gillyflower's deathbed. She's fallen from the Great Work,

and Mr. Sweet abandons her; she realizes the truth that she

was never a partner, only a host. She is gratified, however,

that her daughter has learned an important truth from the

mother.

Clara awakens from her torpor, another version of perpetual

albedo. Her time under glass (glass is a reflective surface)

in a state of perfect passivity had rendered her "frozen in

time." Remember, Gillyflower's alchemy had that effect on

the Doctor, making him a "stiff." True rubedo is achieved

through proper alchemy, by balancing polarity: Clara

awakens in a Steam Cupboard, where Steam is a fusion of

Fire and Water.

To sum up, The Crimson Horror works with these basic alchemical principles mis-applied. The Red Elixir that creates perfection is used only for the base material of the body -- itself a "crimson horror" of blood and flesh and gristle, which will inevitably putrify. Gillyflower seeks perfection of the body, as if this kind of preservation will confer "eternity." But really, she desires immortality; the wise know that eternity is found in the Here and Now.

So, here are a couple other shots that demonstrate the Triune Alcemy:

Here we have Strax in Black, Vastra in a shimmering

mercurial dress, and the Red Elixir between them. Strax is

male, Vastra is female. Both are Monsters, but they take on

human roles; both are "covered." They are joined together

by the Red.

Gillyflower's Organ -- Music is what brings everything

together. To the left, an hourglass -- the Salt, and the

symbol of Death and Decay. In the middle, a Mirror --

silvery, mercurial, receptive. To the right, a Golden Snake --

the base metal turned to gold, the active principle and

suggestive of the venom behind Mr Sweet's kiss.

For those who are interested, we've had this kind of Alchemical storytelling in Who before, and in the magical literary traditions outside of our own little corner of the universe.

So, let's go back to the other Gatiss story this year, Cold War. In the climax to that story, the Doctor confronts Skaldak with the Red Setting on his Sonic; the Doctor is more than willing to sacrifice himself in an act of mutually assured destruction to prevent nuclear war. But it seems that Clara's invocation of the "Songs of the Red Snow" that truly gets the Ice Warrior to chill -- and no wonder, for "the Red Snow" is a much more alchemical mixture, having both the Red Elixir of self-sacrifice and the White Elixir of empathy to draw on -- Clara can empathize because she's a "lost daughter" with a mother, and Skaldak's a "lost father" without a daughter.

And yes, this entirely forms the construction President Snow in the Hunger Games trilogy. Birds on fire, the girl on fire, the Fire Woman! Book One rooted in the Black Coal of District 12, Book Two featuring so much Snow, and Book Three culmanating with a "rose" on Fire.

Or look at Harry Potter's best friends. Hermione -- she's the Hermetic one, cool and reflective, a female Hermes. Ron, on the other hand, is the hothead with the Red Hair. They are the crucible who together give Harry the space to effect his own transformation.

This stuff is everywhere.

The Heroic JourneyQuote:

Now the Great Work is the redemption of spirit from matter; that is, the establishment of the kingdom of God. Jesus being asked when the kingdom of God should come, answered, "When Two shall be as One, and that which is Without as that which is Within."

In saying this, he expressed the nature of the Great Work. The Two are spirit and matter: the within is the real invisible; the without is the illusory visible. The kingdom of God shall come when spirit and matter shall be one substance, and the phenomenal shall be absorbed into the real.

-- "Clothed with the Sun," by Anna Kingsford

Yesterday the absolutely marvelous lonewytch wrote of The Heroic Journey in her wonderful Crimson Horror meta, The Bell Jar. She saved me a lot of writing (Eyes, Chair Agenda, Literature!) but I have one quibble, which is on the subject of the Heroic Journey. This episode isn't a pause -- rather, it's a subversion or a retconning of the heroic stage knowne as Atonement With The Father, which Joseph Campbell was fond of punning as "at-one-ment" with the father.

As is the case with Alchemy, the Heroic Journey is a metaphor for spiritual development. Campbell positions it as a treatise on the mythologies of the world, as a work of literary analysis, but this is about as helpful as saying that Alchemy is the study of chemistry. Taking Campbell literally is just as problematic. There's a lot more to mythology than the Heroic Journey, and taking the Journey as an exercise in academic scholarship misses the point.

Furthermore, the Journey has had an unfortunate effect on Hollywood, where the various stages of the Journey are taken as bullet points in by-the-numbers storytelling. It's doubly problematic that the stages are presented so literally -- lots of Daddy Issues, women as shapeshifters and temptresses, lots of Reluctant Heroes. It makes our stories very predictable, and misses the underlying points of so many stages, like what the metaphor of the Father points to -- our issues with Power and the mystery of Consciousness in the flesh.

I think it's fine to use the Heroic Journey as a developmental structure for a series, a character arc, an episode, as long as it's using the material innovatively, and getting to the underlying heart of what the various stages are really about.

First, while The Crimson Horror doesn't actually feature any Fathers or Gods, we do get plenty of associations that make it easier to see what this story is getting at.

Gillyflower pulls back her robes to reveal Mr. Sweet suckling at her heart, a dark mirror of the familiar iconography of the Sacred Heart of Christ, but with a False God where compassion should reside. (This, by the way, is where the Rosicrucians appropriate some of their imagery, but with a mind to balance polarities they put the Rose at the center of the Cross, combining female and male referents.)

At the dinner table, where we first get a clue to who Mr. Sweet is, we're offered this image:

An empty Red Chair, fit for a king, and haloed by a love seat behind it. This, by the way, is a metaphor for God -- there's an absence, or better yet an invisibility. And the neat thing about this image is that works regardless of whether one's a believer or an atheist -- either the God is absent in the way of a Mystery, because God is behind the Veil of reality, or the chair is empty because there's no god at all.

The Paternoster Gang is named for the "Our Father" prayer; the Latin wording obscures the meaning. Artie and Angie try to blackmail Clara by threatening to reveal her secrets to their father. Gillyflower claims that Ada's blindness is caused by her father's "drunken rage." Gillyflower's "chimney tower" with the Rocket housed within are both great phallic symbols, but they offer a False Ascension.

So, the absent father, but also a lot of veils, curtains, coverings that pulled away in the name of a Reveal.

The word "apocalypse" is often meant to refer to The End of the World (heh, Rose in the Cross back in Series 1) but the etymology of the word actually refers to the Reveal, to an uncovering of a hidden earth-shattering truth. This Reveal is a promise of Alchemy, a promise that the unification of one's dualities will bring about an insight of one's True Self.

Crimson Veils are used to set up Reveals at Gillyflower's "apocalypse" talk. On the one hand we have Ada, living proof of the decay of the mortal body, yet someone who's blindness allows her to see more in people than the flesh covering. Ada's in a Circle, the Divine Feminine, with her mercurial outfit and albedo eyes.

Under the Square we have Sweetville, which is the alternative to Death and Decay -- it's a permanent state of preservation. Being frozen solid. A perversion of the Divine Masculine. And notice how the Circle and the Square are separate, cleaved apart; this is the antithesis of The Great Work.

We even get a Library reference -- people will line up to put their names in the Book of Life to the right.

There's a tremendous amount of fakery in this episode. Fake noise in a fake mill. The fake organ is actually a rocket console. The chimney is a fake, offering a fake ascension. The fake science of the Optogram. Gillyflower fakes spilling the salt, in order to feed Mr. Sweet. Edmund and Effie at the beginning, they were fakes, journalists who infiltrated Sweetville in order to discover its secrets.

Jenny, Clara, and the Doctor all fake their way into Sweetville, for that matter. And Jenny gets another woman to fake a fainting spell! So, yes, fake people. Which means we have fake monsters.

Take Strax. He's a Sontaran warrior. He recommends all kinds of creative violence, yet he makes friends with a smart little boy. He's not a monster, he's played for laughs. He's also someone who wears a costume, pretending to be a Victorian butler, well, except that he is a man of service. But this outfit is ultimately just a robe, a curtain, a veneer.

Vastra's another veiled monster, literally. The lace veil covers her monstrosity, her cold-bloodedness, and though she's strictly The Veiled Detective in this story, we see she's got another warrior side to her as well in A Good Man and Snowmen, especially when she takes the role of Doctor's Companion. The same goes for Jenny, who throws off the cloak of Victorian airs to break out some ninja moves.

The Doctor is a fake monster, and Clara's become like a barbie doll, and they both pretend to be people other than they are; they frequently embody a revelry in genuine inauthenticity.

But there is a character who isn't a fake. She's the one who ascends the Spiral Staircase up to the Doctor's lair, a nice allusion to the imagery of The Snowmen:

Ada is utterly authentic. She speaks her mind (the Red Hair is her active principle) and by virtue of being blind is not prone to judge people by what they're wearing -- whether cloaks of linen or cloaks of life, flesh and blood. Because she never pretends, she is always seen -- though obviously being seen in no way guarantees a compassionate reception, as her relationship to her mother attests.

"Ada" is an interesting name, with multiple referents. The German etymology suggests "nobility" -- and it's true, Ada carries herself as a noblewoman. (And, funny enough, one of the brick-wall posters names Donna!)

But the Hebrew etymology prefers "adornment." And I find that much more interesting, given the curtain/veneer themes of this episode. Plus, it ties into Nabokov's Ada, which concerns itself with twinned realities and the texture of time. "The Past, then, is a constant accumulation of images. It can be easily contemplated and listened to, tested and tasted at random, so that it ceases to mean the orderly alternation of linked events that it does in the large theoretical sense. It is now a generous chaos," says Nabokov, who investigates "its veily substance, with illustrative metaphors gradually increasing, very gradually building up a logical love story, going from past to present, blossoming as a concrete story, and just as gradually reversing analogies and disintegrating again into bland abstraction."

"I wonder," said Ada, "I wonder if the attempt to discover those things is worth the stained glass.

We can know the time, we can know a time. We can never know Time. Our senses are simply

not meant to perceive it. It is like--"

I'm also reminded of Alice in Wonderland, visiting the Pool of Tears: "Dear, dear, how queer everything is today! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next great question is 'Who in the world am I?' Ah, That's the great puzzle!" And she began thinking over all the children she knew, that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them. "I'm sure I'm not Ada," she said, "for her hair goes in such ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all..."

Ada is able to "see" past the Doctor's monstrosity -- not that she's blind to him being a monster, but that being a monster doesn't necessarily mean the person inside is a monster. And it's with a monster that she practices secrecy, the most honest form of fakery -- but even here, being with the monster is a way for her to be authentic. And, perhaps, to be appreciated.

Which brings me to the other side of honesty:

The Coroner. I don't think he's faking his relish for the grisly side of nature, even though he keeps such artifacts behind a curtain of his own.

To be at one with the Father, one must abandon the flesh and identify with the spirit within, and yet one must also realize that the Flesh and Spirit are One; the opposites must be conjoined. Our flesh is that "crimson horror," the cloak of life we wear to be in this world, a cloak that will eventually become threadbare and moth-eaten. We are and are not our appearances -- for everything that partakes of Being partakes of Appearance, and yet these are not the same.

It's a paradox, and a Mystery, and that, I think, is the essence of Atonement With The Father, not faffing about in Daddy Issues.

Narrative CompressionQuote:

Some must needs be satisfied first intellectually. These are regenerate first in the mind; and afterwards they attain to the kingdom.

But some begin from within; and these are the most blessed. For they seek the kingdom first, and the rest is added to them afterwards. These last begin the Great Work in the heart, by means of the affection. And the grace of love attracts the Holy Spirit, and transmutes them from glory to glory, so that the reason, or mind, is suddenly enlightened by the inner reason; and with such the work of regeneration is instantaneous--"in the twinkling of an eye."

-- "Clothed with the Sun," by Anna Kingsford

Me, I happen to like the kind of compression that's used these days to tell Doctor Who stories. Everything's so densely packed I can always find more over several viewings -- but then, I anticipate watching every new story several times. I look forward to watching every new episode several times! I don't watch, say, Game of Thrones in the same manner. I only need or care to see an episode of that once, in general, certain scenes excepting. Same goes for just about everything else I watch.

So, let's talk about story compression for a bit, because I think this *is* an issue in Doctor Who these days -- hell, it came up at an academic symposium on the show at DePaul University last weekend, though sadly there wasn't any time to actually, you know, explore it.

First off, it's not just Doctor Who. All television has embraced compression to some extent. None as much as Who, but then Who is doing things that no other show on TV can pull off right now.

In fact, compression is at the heart of filmmaking -- it's inherent in the cut. So we already know how to stitch stories together. And because we've seen so many stories, and understand all the accreted conventions of televisuals so well, we not only fill in the narrative gaps produced by editing, we fill in those gaps with amazing detail based on the particular kinds of tropes and references the work employed.

Doctor Who is a particularly visual show, more visual than anything else on TV right now. It's loaded with imagery, and importantly, it's loaded with recurring imagery. The meanings of those images accumulate over time. Interestingly, the FlashBack sequence plays on this by using static images, flashes before our eyes, with a veneer of old-time photography/filmmaking informing the aesthetic. Just a few choice scenes are all we need to get the plot, while the aesthetics of the sequence provide all we need to know about setting and mood and feel.

Here's the thing: we just had an episode a couple weeks ago that played with photography. The Doctor went back in time and took photos throughout the gazillion years of Earth's history to tell the story of someone who's nearly frozen in place. Last week, we entered the Heart of the TARDIS, which was frozen in time. And this week, we see the Doctor stiff as a board in crimson, and Clara practically petrified under glass -- and photographs are used to help unravel the mystery, which is what we get at the beginning of the story.

For example, on the wall behind Strax and Vastra, we see a bunch of posters, still images, and they all have clues regarding the story. The Apocalypse and Gilliflower. "Come see the Freaks," another posters announces; Gilliflower calls our heroes "freaks" at the end. "Shooting Galleries" and "Fireworks," both present in the climax. "Human Wax Works," pointing to Clara under the Bell Jar. They're even prophetic -- the Circus in reference to the Nightmare Fair of next week's previews, a suggestion that Donna might be returning, and at the bottom another pointer to The Rose and Crown where Clara used to work.

So we are overloaded with images, and have to actively engage with the text in order to "put it all together." Obviously, this goes against the grain of passive viewing, and even begs for something resembling "work" on the part of the viewer, but on the other hand it provides a distinctly immersive environment -- because we have to do what the heroes of the story have to do in order to resolve the story, and to make sense of the mystery.

I have no doubt this is absolutely intentional.

So, thinking about the current trend in Who, if we hadn't had the hook-end to Crimson Horror, would that have changed the aesthetic considerations of the story? I think not. Given an extra two or three minutes of running time, we would have gotten an extra two or three minutes of highly compressed storytelling. That aesthetic and discourse have already been chosen, comprising the weft of the narrative structure -- making us the weft of the narrative structure.

In fact, this is exactly what the children do in the hook-end. They have constructed the entire narrative of Clara's season from a few select images, and in so doing they have put themselves into the story itself. Which is what compressed storytelling asks us to do. The final scene is a great example of this.

We've seen Clara go home after an adventure before -- twice before, actually. So this particular action has already been established within the show's narrative conventions as something that happens. The surprise here isn't that she's home, it's more of a "oh, we haven't seen Clara do this in a few weeks." It isn't out of nowhere.

There's a "bridge" between this scene and the end of the "proper story": We get repeated dialogue of "the boss" from the previous scene -- we can infer that they've come straight from Victorian Yorkshire, and we haven't missed any important story beats. There's also the musical score tying the two scenes together -- not incidentally, the score is Clara's Theme, orienting us to her character; remember, the last beat in Yorkshire is the Doctor blowing off Jenny's request for an explanation of Clara.

We see Clara sneak into the house and check herself out in the mirror; she's changed her clothes. It's coupled with the shot of the TARDIS disappearing on the security camera, an effective invocation of The Bells of Saint John, which was all about the Doctor finding Clara and convincing her to travel with him; with two repeated shots, we're back into the long arc of the story. In Doctor Who, many of the scenes that serve to remind us of the Long Arc bookend an episode.

So we get a scene that mirrors action from several previous episodes, and that literally shows us the kind of "reading" the show expects of its viewers -- the "implied reader" is the construct of every author, the imagined audience for whom we write. Doctor Who is written with savvy kids in mind, and it's very self-aware of the narrative conventions it employs while doing so. This is a mark of good writing.

The other thing this scene accomplishes is to highlight Clara's internal conflict, and where that conflict mirrors the Doctor's own issues. She's presented with a choice: let the kids "in on it" or risk losing this particular familial relationship -- for the kids have tangible narrative evidence, and trying to explain that evidence to the father will be problematic; even if he doesn't believe them, he might decide it's time for Clara to go.

The photo from Snowmen highlights that as she's been hiding a true part of herself from this family, so too has the Doctor been keeping secrets from her; one one fell swoop, she reveals the secret of her time-traveling ("No, I was in Victorian Yorkshire") to the kids, just as the Doctor's secret is revealed to her. The cat's out of the bag for all parties concerned.

Any time we get into character motivation and internal conflict, we have good writing. The choice Clara faces is between her need for travel and her need for family -- and her alchemical solution will be to travel with family. The Doctor needs his privacy, needs companionship, needs "to solve the mystery" -- his alchemical solution has been to travel with the mystery while keeping secrets from her, and now this choice has been taken away from him, he's gonna have to fess up, something he doesn't like to do... and we like seeing characters having to do things they don't like to do, because so much of our own lives are about doing things we don't like to do. It gets to the heart of our own internal conflicts.

In short, the current style of Doctor Who begs for a close reading, and the text itself (which now engages in the "screencapping" of close readers) confirms that the "leap of faith" required to interpret the barrage of images will, as it does for Artie and Angie, confer the ability to travel with the Doctor, in all of Time and Space.

This too, of course, is a metaphor. Angie's jumper suggests what the metaphor is actually about:

As always, thanks for reading!