A Deist Nightmare

'Cause there's nothin' strange

About an axe with bloodstains in the barn.

There's always some killin'

You got to do around the farm.

-- Tom Waits, "Murder in the Red Barn"

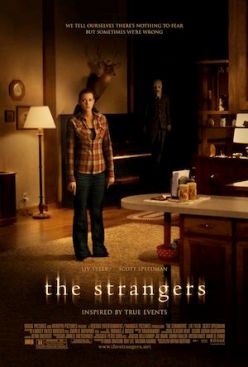

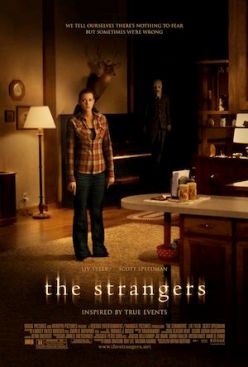

As the Waits song does, Bryan Bertino's The Strangers layers discrete and shadowed detail to build a portrait of the rural and remote as a place where cruelty can be expected, where animal and human nature can confuse, where the mundane and the extreme do-si-do. Sharp images gesture into dark corners, leaving scenes starkly painted and bigger stories largely untold. In both, the folk is evoked to invest our notions of populism with fear.

But where Waits' portraiture creates a truly rural, poverty-twisted, rootless, multicultural, carnival atmosphere -- a serious updating of the Southern grotesque -- Bertino's is something else. The barn is a tool shed, the house a rancher summer home, and the folks the media-infused middle class as it sits between child- and adult-hood. The beautiful and polished couple (Tyler and Speedman) take their places in the allegory -- one filled with an over-zealous rush for marriage and the other befuddled by an abstract not-readiness. They fill the shoes of both the quixotic and the over-timid of this class and age bracket pretty well. All around them is something their fathers bought: the anachronistic and organic music playing on the record player, the hunting rifles to put heads on the wall, all the tools needed for people playing house to cut and burn with. And they are both over-confident and overwhelmed by the prospect of playing this game their parents have made: marriage-house-security-family.

The genre is house invasion, and The Strangers is an essay on the genre and its points, taking its position between Halloween and Funny Games. As such, its references shouldn't be taken as attempts at originality but as attempts to get some yield out of the friction between those in its pedigree, its mothers and fathers. If Bertino tips his hat visually to the scary remoteness of the rural but pulls short of commenting on the lower-class indigenous that Waits does, he also manages to merely dogear the townie, hormone-steeped adolescent rituals of Halloween as well as the modern insularity of the vacationing family unit in Funny Games. The question is What is Bertino trying to get at by smudging these together?

He borrows several points for his thesis. The very security and privacy that the house/home is intended to provide can ironically render you both exposed and walled-in. The warm browns and golds of this rancher soon become a baroque cabin whose sharp, in-turning corners can't be turned fast enough and whose walls bluntly mock all escape. Outside, the flat, pine-treed landscape teases you with the idea of open-ness, urges you to run, until you realize the space -- so unpopulated, wide, and, therefore, never-ending -- might as well be a wall, too, for all the good it could do you. The happily-ever-after that marriage promises is also fraught; sweet union forsakes the rebelious independence, projected innocence, and supposedly consequentless gaming of youth. Children are easily (mal)formed by accident (parental negligence or mis-step) and can suddenly become the monsters in their fairy tales. Not knowing how to shoot daddy's gun or use his transistor radio indicates how unprepared you are to "grow up," much less have kids of your own ... since they will surely turn on you with all the externalized rage of your own repressed childhood fantasies and bite you in the face. Or coldly, scientifically gut you after batting you around like a mouse under paw.

We know this. We've seen these movies.

I am somewhat reminded of my own childhood memories, growing up on a farm in the 70s. There was the idea that -- having only a route number for an address -- it would take emergency vehicles ages too long to reach us should emergency come knocking. I remember the creak of farmhouse stair, the blurring of ghost and intruder, sense and paranoia. I remember the wooden slat I kept -- swingable, under my bed. I remember seeing the yellow Mustang, idling, at night, at the foot of our hill, watching me watching them, when my parents were away, and hearing, during the day, about the string of break-ins just over the hill. I remember watching the odometer to realize our nearest neighbors were .75 miles away. I remember sitting with my great-grandmother, in the dark, scared, on Halloween, as a group of teenagers drove doughnuts on her yard grass, yelling and throwing bottles at the side of the house. I remember all the churches talking about backmasking in all the kids' music and how Satanism was on the rise. I remember talking to a friend about finding the spraypainted walls, ordered bottles, and burned candles in the fire-gutted AME church down the gravel road.

And it is this latter that, I think, Bertino is trying to take us to. Culturally, our horrors have a history, and history has a little way of repeating. If the era of Funny Games shows us that our middle-class, safely binoculared, voyeuristic interest in violence can implicate us in such violence -- even unknowingly invite such violence into our supposedly safe homes -- and if the 70s era of Halloween re-endorsed our cultural moralism by invoking and fixating us on evil understood confusingly through the lens of vague religiosity and science (especially psychology), what are we to make of the heavy-handed religious elements at the end of The Strangers?

When the teen evangelists offer the post-kill kids a tract and ask, "Are you a sinner?" and the girl replies, "Sometimes" and takes it, we know there is a moral. The killers -- aside from their masks -- are dressed so normally, so much like they have been nabbed out of school or church, and we know that -- despite their actions -- they are not biologically monsters. The fact we never see their faces makes them, collectively, "Everyteen" figures. So, essentially, we know that 1) something has happened to these kids to lead them to this action and 2) it could happen to any and -- *gulp* -- many kids (as the opening "stat" implies by its sheer numbers). The only clues we really have as to these kids' motivation are the fact they say outright they do it "Because you were home" and this little, almost-gentle exchange between teen killer and teen evangelist. The first clue only betrays the impersonal, convenient, and somewhat random nature of the crime as well as that it is a vengeful act pitted against the typical "home" as they see it.

The religious exchange at the end of the film, I think, warns us against a return to the kind of over-fervent, idealistic psychology typical of fundamentalism, of evangelism. Possibly, Bertino sees us as having already re-entered a period of revived, rampant fundamentalism, where our liberal hesitation to name its excesses and condemn it, is built on a kind of voyeuristic nostalgia for the natural, the un-analyzed -- the zealous rather than the doubt-full. But since this exchange happens at a kind of country crossroads, between kids using various evolutions of transportation (bikes and a truck), from teen to teen, the scene serves, to me, as a kind of cinch in the essay, a warning about where our teens may be going if we allow them to indulge in either the excess of belief that becomes violent and fundamentalist or in the excess of doubt that becomes utterly relativistic, timid of judgement and choice.

I think The Strangers warns us of backing ourselves into such a polarized corner.

Unfortunately, I also believe Bertino leaves us with too little to go on, fans our paranoia rather than stoking our critical fire. Still, he builds his frightful house, image by intriguing image, and goads us to flee it for ... God knows where.

About an axe with bloodstains in the barn.

There's always some killin'

You got to do around the farm.

-- Tom Waits, "Murder in the Red Barn"

As the Waits song does, Bryan Bertino's The Strangers layers discrete and shadowed detail to build a portrait of the rural and remote as a place where cruelty can be expected, where animal and human nature can confuse, where the mundane and the extreme do-si-do. Sharp images gesture into dark corners, leaving scenes starkly painted and bigger stories largely untold. In both, the folk is evoked to invest our notions of populism with fear.

But where Waits' portraiture creates a truly rural, poverty-twisted, rootless, multicultural, carnival atmosphere -- a serious updating of the Southern grotesque -- Bertino's is something else. The barn is a tool shed, the house a rancher summer home, and the folks the media-infused middle class as it sits between child- and adult-hood. The beautiful and polished couple (Tyler and Speedman) take their places in the allegory -- one filled with an over-zealous rush for marriage and the other befuddled by an abstract not-readiness. They fill the shoes of both the quixotic and the over-timid of this class and age bracket pretty well. All around them is something their fathers bought: the anachronistic and organic music playing on the record player, the hunting rifles to put heads on the wall, all the tools needed for people playing house to cut and burn with. And they are both over-confident and overwhelmed by the prospect of playing this game their parents have made: marriage-house-security-family.

The genre is house invasion, and The Strangers is an essay on the genre and its points, taking its position between Halloween and Funny Games. As such, its references shouldn't be taken as attempts at originality but as attempts to get some yield out of the friction between those in its pedigree, its mothers and fathers. If Bertino tips his hat visually to the scary remoteness of the rural but pulls short of commenting on the lower-class indigenous that Waits does, he also manages to merely dogear the townie, hormone-steeped adolescent rituals of Halloween as well as the modern insularity of the vacationing family unit in Funny Games. The question is What is Bertino trying to get at by smudging these together?

He borrows several points for his thesis. The very security and privacy that the house/home is intended to provide can ironically render you both exposed and walled-in. The warm browns and golds of this rancher soon become a baroque cabin whose sharp, in-turning corners can't be turned fast enough and whose walls bluntly mock all escape. Outside, the flat, pine-treed landscape teases you with the idea of open-ness, urges you to run, until you realize the space -- so unpopulated, wide, and, therefore, never-ending -- might as well be a wall, too, for all the good it could do you. The happily-ever-after that marriage promises is also fraught; sweet union forsakes the rebelious independence, projected innocence, and supposedly consequentless gaming of youth. Children are easily (mal)formed by accident (parental negligence or mis-step) and can suddenly become the monsters in their fairy tales. Not knowing how to shoot daddy's gun or use his transistor radio indicates how unprepared you are to "grow up," much less have kids of your own ... since they will surely turn on you with all the externalized rage of your own repressed childhood fantasies and bite you in the face. Or coldly, scientifically gut you after batting you around like a mouse under paw.

We know this. We've seen these movies.

I am somewhat reminded of my own childhood memories, growing up on a farm in the 70s. There was the idea that -- having only a route number for an address -- it would take emergency vehicles ages too long to reach us should emergency come knocking. I remember the creak of farmhouse stair, the blurring of ghost and intruder, sense and paranoia. I remember the wooden slat I kept -- swingable, under my bed. I remember seeing the yellow Mustang, idling, at night, at the foot of our hill, watching me watching them, when my parents were away, and hearing, during the day, about the string of break-ins just over the hill. I remember watching the odometer to realize our nearest neighbors were .75 miles away. I remember sitting with my great-grandmother, in the dark, scared, on Halloween, as a group of teenagers drove doughnuts on her yard grass, yelling and throwing bottles at the side of the house. I remember all the churches talking about backmasking in all the kids' music and how Satanism was on the rise. I remember talking to a friend about finding the spraypainted walls, ordered bottles, and burned candles in the fire-gutted AME church down the gravel road.

And it is this latter that, I think, Bertino is trying to take us to. Culturally, our horrors have a history, and history has a little way of repeating. If the era of Funny Games shows us that our middle-class, safely binoculared, voyeuristic interest in violence can implicate us in such violence -- even unknowingly invite such violence into our supposedly safe homes -- and if the 70s era of Halloween re-endorsed our cultural moralism by invoking and fixating us on evil understood confusingly through the lens of vague religiosity and science (especially psychology), what are we to make of the heavy-handed religious elements at the end of The Strangers?

When the teen evangelists offer the post-kill kids a tract and ask, "Are you a sinner?" and the girl replies, "Sometimes" and takes it, we know there is a moral. The killers -- aside from their masks -- are dressed so normally, so much like they have been nabbed out of school or church, and we know that -- despite their actions -- they are not biologically monsters. The fact we never see their faces makes them, collectively, "Everyteen" figures. So, essentially, we know that 1) something has happened to these kids to lead them to this action and 2) it could happen to any and -- *gulp* -- many kids (as the opening "stat" implies by its sheer numbers). The only clues we really have as to these kids' motivation are the fact they say outright they do it "Because you were home" and this little, almost-gentle exchange between teen killer and teen evangelist. The first clue only betrays the impersonal, convenient, and somewhat random nature of the crime as well as that it is a vengeful act pitted against the typical "home" as they see it.

The religious exchange at the end of the film, I think, warns us against a return to the kind of over-fervent, idealistic psychology typical of fundamentalism, of evangelism. Possibly, Bertino sees us as having already re-entered a period of revived, rampant fundamentalism, where our liberal hesitation to name its excesses and condemn it, is built on a kind of voyeuristic nostalgia for the natural, the un-analyzed -- the zealous rather than the doubt-full. But since this exchange happens at a kind of country crossroads, between kids using various evolutions of transportation (bikes and a truck), from teen to teen, the scene serves, to me, as a kind of cinch in the essay, a warning about where our teens may be going if we allow them to indulge in either the excess of belief that becomes violent and fundamentalist or in the excess of doubt that becomes utterly relativistic, timid of judgement and choice.

I think The Strangers warns us of backing ourselves into such a polarized corner.

Unfortunately, I also believe Bertino leaves us with too little to go on, fans our paranoia rather than stoking our critical fire. Still, he builds his frightful house, image by intriguing image, and goads us to flee it for ... God knows where.