Chrono Trigger: An Existentialist Reading (Part IV)

Magus' Castle and the fall of the reptites are two portions of Chrono Trigger that require a lot of interpretation. For that reason, and because I want to get the whole Zeal arc in one article next time, I'm covering only a short portion of the game this week. Fortunately, Magus's Castle and the return to 65,000,00 are linked thematically; they both treat the subject of death and critique the conflict of good versus evil.

Synopsis, Part Four

Magus' castle is every inch the Tower of the Evil Wizard, complete with bats fluttering around it and a creepy statue on top. Inside, the player finds it nearly empty. It has two main forks, but both contain only weird, non-combat encounters: a group of children who want to be played with, for example, and illusions of the party's closest family and friends (Crono's mom, Marle's father, Queen Leene for Frog, Lucca for Robo, Taban for Lucca). Both paths are dead ends. After exploring both, the player finds that a save point has appeared in the first room of the castle. It is a false save point, though, and when the characters touch it, Ozzie appears. He summons monsters and then vanishes.

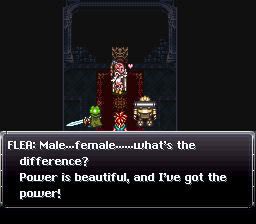

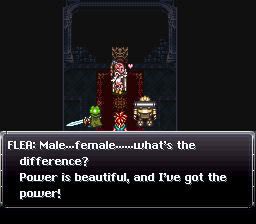

After the battle, the player must once against explore both branches of the castle, but now the weird encounters have turned into battles. The children turn into monsters; the girl who said "help me" now demands that the characters end her suffering and transforms into an undead skeleton; and the illusions of the party's companions attack them, each one unfolding somehow into a whole group of monsters. The ends of the paths are now guarded by Magus' other two generals, Slash and Flea. Slash is a dark swordsman who is deeply loyal to Magus; his blue skin and strange shape confirm that he is a Mystic, one of the race of monsters that Magus leads against the human kingdom of Guardia. Slash wields a katana (Crono can use it after Slash is defeated), giving the impression of Slash as a samurai in Magus' service. Flea is a magician who seems to focus on charms and other bewildering effects. Though Flea appears to be a woman, he is actually a man (perhaps a cross-dresser, perhaps transgendered). Flea is open about his sex, but doesn't find it very important, stating: "Male... female... what does it matter? Power is beautiful, and I've got the power!" Both Slash and Flea speak with Frog, making it clear that they have met him before. Both are encountering him for the first time since his transformation into a frog, though, and underestimate his strength. When Slash and Flea have both been defeated, the false save point in the first room of the castle transports the characters to take on Ozzie. After leading them through a series of trapped rooms and other obstacles, Ozzie surrounds himself in an impenetrable barrier and brags that Magus is already summoning Lavos. The characters are able to open a trapdoor under Ozzie, effectively defeating him. Finally, they confront Magus.

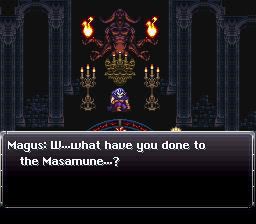

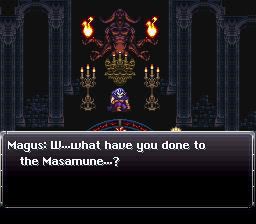

Crono and his allies find Magus in his sanctum, midway through a summoning ritual. Magus is dubious about Frog's power, but is willing to battle him if he wishes. He notes that Frog has repaired the Masamune, but doesn't believe that this will help. After a difficult battle, Magus is defeated. Just then, Lavos begins to awaken. Magus reveals to the party that he did not create Lavos, but is only attempting to summon him. A massive, uncontrolled gate opens and sucks the party in. After a strange dream sequence (where Crono awakens to Marle telling him to stop mooching off the king and get a job), the party awakens in Ayla's hut in 65,000,000. She tells them that she had a strange dream telling her to visit the Mystic Mountains, and found them there unconscious.

In 65,000,000, the fight against the reptites is intensifying. While Ayla's Ioka Village fights against the reptites, the other humans in Laruba Village hide from the reptites. Laruba Village is burned down after one of Ayla's visits and the villagers understandably blame Ayla. When Ayla goes to speak to the chief of the Laruba and witness the destruction, she decides to end the conflict permanently. With help from the Laruba, she summons pterodactyls and flies to Tyranno Lair with Crono and his friends to confront Azala.

At Tyranno Lair, Ayla frees captive humans (including Kino) and fights her way to Azala. Atop Tyranno Lair, Azala summons the giant dinosaur Black Tyranno; throughout the battle with the dinosaur, a red star hangs ominously in the sky. After the dinosaur's defeat, Azala tells Ayla that though she has won and the reptites will die out, to be replaced by humanity, the falling of the red star will scorch the earth, then herald in an ice age. The humans, Azala says, will wish that they had died out with the reptites. Ayla offers to rescue Azala from the tower, where the red star is about to land. Azala declines, recognizing that the time of the reptites is over.

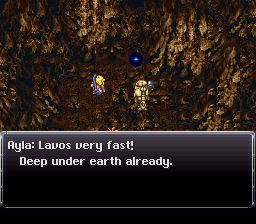

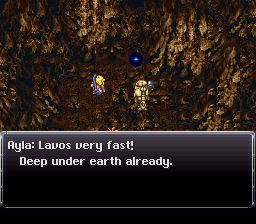

We cut to a spiky sphere hurtling through space toward earth. When it strikes, it creates a tremendous crater where Tyranno Lair used to stand. Ayla names the phenomenon Lavos, which means "big fire." Going to investigate the crater and perhaps slay Lavos at the beginning of his life-cycle, the party discovers that he has already burrowed too deep into the earth to pursue. He has left a gate in his wake, however. The party uses the new gate and finds itself in a cave in B.C. 12,000. Outside, the lush green of 65,000,000 has been replaced by a featureless plain of snow.

Comments

Magus' Castle

Magus' Castle is one of Chrono Trigger's most memorable sections and serves a very interesting purpose in the game. The castle's motif of death makes it a rare confrontation with darkness in a game that maintains a mostly-lighthearted tone. Yet, the equally-strong motif of illusion (and the game's later revelations) make the castle's meaning more ambiguous. In some sense, it is a confrontation with evil. Yet the story of the brave hero vanquishing the evil wizard is very misleading here, and the game continually reminds us that things are not as they seem.

The whole castle is haunted by death. Seemingly human beings transform into undead creatures; monstrous overseers watch as skeletons attack each other in futile battle; Magus hears the Black Wind, the game's recurring symbol for impending death; and Magus and his three generals all remind Glenn of Cyrus' death, which hangs over all the events in the castle as a spur to vengeance and as a reminder that courage and heroism can't stave off the void. Despite the occult trappings and Magus' position as leader of the Mystics (Demons, in the original Japanese), the portrayal of death here evokes the reaper rather than the devil. Death is a grim and inevitable extension of life. The two sets of skeletons sum it up; one group is forced to dance in celebration of Lavos (who represents total obliteration) while the other skeletons fight endlessly among themselves, seemingly oblivious to the fact that they are already dead. Death mocks the living and strips them of their individuality, as in the medieval danse macabre. Human behavior, even the noble human behavior of a hero like Cyrus, leads inevitably to the indifferent grave. What's the function of this portrayal narratively, and what does it say about the game's stance on death?

The death motif can only be understood in light of the illusion motif. The meta-game manipulation of save points, the illusions of the party's loved ones and even Flea's false appearance of femininity all lead the player (not the characters, but the player) to suspect deception, which turns out to be exactly what's afoot. The deception is twofold. On a narrative level, the player discovers the Magus did not create Lavos. The evil wizard, who would be the ultimate villain in a more conventional game, is replaced as antagonist by an amoral and seemingly invincible force for destruction. This narrative bait-and-switch ends the clichéd sword-and-sorcery arc and reveals the true stance on evil and death that lies beneath the surface of that pastiche. Just as Lavos is revealed to be something much older and more powerful than a mere villain, death is revealed to be a force far beyond the reach of our facile stories of good and evil. This is the second deception, this one meta-narrative rather than narrative. We as players have been fooled into believing in a myth of good versus evil that turns out to be false in almost every respect. As I discussed last time, Frog is anything but the Destined Hero of myth and fantasy cliché. We are beginning to find that Magus is not what we thought he was either and that the trappings of evil are equally as artificial as the trappings of heroism that Frog needed -- psychologically -- to confront Magus. It's all a pose, from Slash's voluntary adherence to Magus' law to Flea's cutesy-girl act to Magus' (as-yet undiscovered) fraud.

In the midst of all this illusion, there are two undeniable truths that move the plot forward. First, that in Frog's hands the Masamune is mysteriously powerful enough to harm Magus, despite its failure to do so when wielded by Cyrus. Magus asks Frog, "W...what have you done to the Masamune...?" A complete discussion of the Masamune's power will have to wait for a later article, but it suffices for now to point out that Masa and Mune themselves identified the Masamune's most important source of power as the purpose to which it is put. It is what Frog is doing when he assaults Magus, not just the blade he is using, that can pierce all of Magus' magic. Frog is beginning to discover the secret weapon that can cut through all the illusions of the castle and through death itself. That weapon is authenticity.

The second undeniable truth of Magus' Castle is Lavos. When Lavos is awakened at the end of the battle, he tears time itself apart, creating an impossibly huge gate and scattering both the heroes and the villain across time. This scene calls to mind Rumi's poem about Solomon and the Gnats. It is a fitting capstone to this subversion of the Hero's Journey that when the heroes and the villain finally reach the metaphysical power they have been fighting over, their little morality play is swept away indiscriminately in the face of reality. Though everything else in this story arc is somehow false, the power of Lavos -- the implacable power of time and truth -- is real.

65,000,000 BC and the Defeat of Azala

With the fall of the reptites and the appearance of Lavos in place, we can properly analyze the time period of 65,000,000. It is a fairly conventional "caveman era," but it holds special interest for an existentialist reading because it portrays the roots of humanity, the beginning of humanity's struggle against the void (represented by Lavos), and the collapse of a civilization.

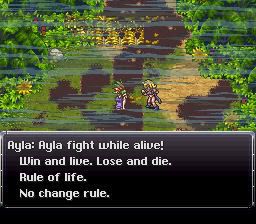

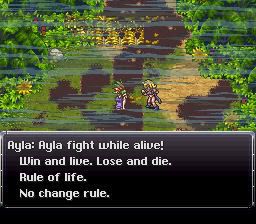

The reptites, especially Azala, are interesting antagonists because they are not really evil. We are encouraged to view the competition between the humans and the reptites as an ecological struggle, not a moral one, and in terms of Darwinian fitness the reptites seem to be the rightful winners of the battle. They are smarter, tougher and more "civilized" than the humans, to be sure. The Laruba Tribe takes this position and chooses to hide from the reptites. Ayla, in contrast, recognizes that conflict is the only path to survival: "Win and live. Lose and Die. Rule of life. No change rule." This statement seems simple (and the caveman-talk doesn't help) but actually sums up the thematic climate of 65,000,000 very nicely. Victory and domination are not just means to survival, but they are survival. The Laruba are portrayed in the game as cowardly and endlessly willing to absorb punishment rather than risking battle. This negative portrayal seems to sanction Ayla's view that surviving alongside the reptites is impossible. The only way for one species to live is to kill the other. Note too that this conflict is not set up by either species, but by nature itself. It is the "rule of life." It is by the light of this radical idea that we must read the tragic defeat of Azala.

Azala is for the reptites what Ayla is for the humans. Just as Ayla is the epitome of savage strength, Azala is the epitome of advanced civilization: smart, ruthless and society-minded. And while Ayla seems prophetic in her insistence that humans will take possession of the earth, Azala shows a prescient suspicion that the reptites are doomed. Yet, Azala too recognizes the "rule of life" and fights to the end. Like the personal struggles of existentialism, which cannot ultimately be "won, the reptites' struggle is one that would be nonsensical to abandon even in the face of certain annihilation. People cannot escape death by giving up their struggle against it, and neither can civilizations. It is key to understand that the game commends both Ayla and Azala for fighting the final battle as representatives of their respective species because they are both fighting against death, as symbolized by the red star that hangs over their battle. The message, I believe, is that while death cannot be overcome, the struggle against it is a defining fact of life, and cannot be evaded or ignored. We may turn to the Theater of the Absurd for a similar view of death; there, life and death coexist in irrational but real harmony, and attempts to reconcile them logically are doomed. It is as though two separate realities exist, one of life and one of death, and that the passage between them is as inexplicable as it is inevitable because the logic of life does not apply to death. The two species of 65,000,000 demonstrate this gulf aptly. The fall of the reptites is the end of a civilization that is featured only peripherally in the game, but is presumably as vast and advanced as human civilization will become. Though the stories of those civilizations intersect briefly, the logic of one story cannot apply to the other, and the vast stretch of time ruled by humanity is only an unsettling blank from Azala's --perfectly valid! -- perspective. As Azala says of the Reptites, "We have no future." This is, in some sense, the heart of the existential struggle; the fact that death and the void, though "merely" objective, can cross into our subjective existences, dissolving the personal worlds that we all build and inhabit. The fall of the reptites is the death of a meta-narrative and (in combination with the descent of Lavos) the birth of another.

Lavos, part 1

It is only after Azala's defeat (about halfway through the game!) that the player understands the nature of Lavos, and there are still surprises in store. Let's review what we know about Lavos so far:

Lavos is a giant monster who fell from space in 65,000,000 B.C. His impact formed a huge crater and cast the earth into an ice age. Since then, Lavos has drained energy from the planet and grown ever-stronger. In 2300 A.D. he erupts from the earth and ravages the surface of the planet, destroying civilization and nearly wiping out humanity.

Up until this middle section of the game, Lavos seems just like any other video game monster. It is only with the revelation of his history that he becomes something more like a cthuloid horror or a force of nature. This is a key transformation because the drastic change to the "antagonist" recasts the game's heroes. Up until now, Crono and his allies have been heroes in the traditional sense, as epitomized by their fight against Magus. After bearing witness to Lavos' descent and discovering his insidious power, they learn that their enemy represents total negation, not evil. Unlike the classic hero, who struggles to return the world to a lost equilibrium, the heroes of Chrono Trigger are trying to stop or reverse a process that dates from the beginning of human civilization -- and, to some degree, defines it.

Lavos has been attacked as something of a generic villain, which I think is a misunderstanding. He is not really a villain; he is a fact. As such, he's not akin to his contemporaries in other Squaresoft games, like Sephiroth and Kefka. Lavos is linked most obviously to Lovecraft's Great Old Ones, but also possesses something of the consuming negativity of the dead God of Nietzsche. Ultimately, he acts as an incarnation of the abstract menaces of Chrono Trigger, Time and Death. Like those forces, Lavos's brand of destruction is as meaningless as it is virulent. In both 65,000,000 and 1999, Lavos utterly destroys a whole civilization for no reason, denying them even the final consolation of making sense of their own demise. The world of 2300 makes it clear that Lavos leaves only oblivion in his wake, and this too is a substantial contrast to the classic villain, who seeks to instate a new order or at least to improve his own state. In further parallel to Time and Death, Lavos is a disaster endemic to human existence. Because Lavos fell at the dawn of human civilization -- and in fact created the ice age that permitted humanity to become the planet's dominant species -- the whole of human history takes place in the shadow of his mindless, ravenous oblivion. As Beckett puts it, "the gravedigger puts on the forceps."

Lavos is a symbol of death, nothingness and time's unstoppable flight toward decay. In this light, the struggle against Lavos is one with clear existentialist antecedents. Nietzsche's dual obsession with God's nonexistence and His corrupting influence on humanity mirrors the fight against Lavos, who is physically and historically central to the human world and yet ultimately obliterates it. One might also compare Lavos to Death in Bergman's The Seventh Seal, insofar as he is an amoral force for destruction that ultimately dissolves all individuality and meaning... or to Godot in "Waiting for Godot," who is the teleological void that dooms the attempts of Gogo and Didi to establish any meaning or reason. I don't mean to say that these existentialist works are all perfectly analogous, only that they are variations on the theme of the empty center, the void that supports the structure of the human world, yet must finally negate it from the inside out.

There's a lot left to say about Lavos, but it can wait for later posts, after the game reveals strange new sides of him. It suffices for now to establish that he is one of the keystones of the existentialist reading of Chrono Trigger. If Lavos represents the unreasoning destructive power of Time and Death, then the overarching fight to rescue the planet from his hunger is an existentialist struggle to salvage meaning from nothingness. One can read almost the whole game in this light.

Next Time: Life, Time, Reason and the transcendence of Dreamstone

But First (Maybe): Elves, elv

Synopsis, Part Four

Magus' castle is every inch the Tower of the Evil Wizard, complete with bats fluttering around it and a creepy statue on top. Inside, the player finds it nearly empty. It has two main forks, but both contain only weird, non-combat encounters: a group of children who want to be played with, for example, and illusions of the party's closest family and friends (Crono's mom, Marle's father, Queen Leene for Frog, Lucca for Robo, Taban for Lucca). Both paths are dead ends. After exploring both, the player finds that a save point has appeared in the first room of the castle. It is a false save point, though, and when the characters touch it, Ozzie appears. He summons monsters and then vanishes.

After the battle, the player must once against explore both branches of the castle, but now the weird encounters have turned into battles. The children turn into monsters; the girl who said "help me" now demands that the characters end her suffering and transforms into an undead skeleton; and the illusions of the party's companions attack them, each one unfolding somehow into a whole group of monsters. The ends of the paths are now guarded by Magus' other two generals, Slash and Flea. Slash is a dark swordsman who is deeply loyal to Magus; his blue skin and strange shape confirm that he is a Mystic, one of the race of monsters that Magus leads against the human kingdom of Guardia. Slash wields a katana (Crono can use it after Slash is defeated), giving the impression of Slash as a samurai in Magus' service. Flea is a magician who seems to focus on charms and other bewildering effects. Though Flea appears to be a woman, he is actually a man (perhaps a cross-dresser, perhaps transgendered). Flea is open about his sex, but doesn't find it very important, stating: "Male... female... what does it matter? Power is beautiful, and I've got the power!" Both Slash and Flea speak with Frog, making it clear that they have met him before. Both are encountering him for the first time since his transformation into a frog, though, and underestimate his strength. When Slash and Flea have both been defeated, the false save point in the first room of the castle transports the characters to take on Ozzie. After leading them through a series of trapped rooms and other obstacles, Ozzie surrounds himself in an impenetrable barrier and brags that Magus is already summoning Lavos. The characters are able to open a trapdoor under Ozzie, effectively defeating him. Finally, they confront Magus.

Crono and his allies find Magus in his sanctum, midway through a summoning ritual. Magus is dubious about Frog's power, but is willing to battle him if he wishes. He notes that Frog has repaired the Masamune, but doesn't believe that this will help. After a difficult battle, Magus is defeated. Just then, Lavos begins to awaken. Magus reveals to the party that he did not create Lavos, but is only attempting to summon him. A massive, uncontrolled gate opens and sucks the party in. After a strange dream sequence (where Crono awakens to Marle telling him to stop mooching off the king and get a job), the party awakens in Ayla's hut in 65,000,000. She tells them that she had a strange dream telling her to visit the Mystic Mountains, and found them there unconscious.

In 65,000,000, the fight against the reptites is intensifying. While Ayla's Ioka Village fights against the reptites, the other humans in Laruba Village hide from the reptites. Laruba Village is burned down after one of Ayla's visits and the villagers understandably blame Ayla. When Ayla goes to speak to the chief of the Laruba and witness the destruction, she decides to end the conflict permanently. With help from the Laruba, she summons pterodactyls and flies to Tyranno Lair with Crono and his friends to confront Azala.

At Tyranno Lair, Ayla frees captive humans (including Kino) and fights her way to Azala. Atop Tyranno Lair, Azala summons the giant dinosaur Black Tyranno; throughout the battle with the dinosaur, a red star hangs ominously in the sky. After the dinosaur's defeat, Azala tells Ayla that though she has won and the reptites will die out, to be replaced by humanity, the falling of the red star will scorch the earth, then herald in an ice age. The humans, Azala says, will wish that they had died out with the reptites. Ayla offers to rescue Azala from the tower, where the red star is about to land. Azala declines, recognizing that the time of the reptites is over.

We cut to a spiky sphere hurtling through space toward earth. When it strikes, it creates a tremendous crater where Tyranno Lair used to stand. Ayla names the phenomenon Lavos, which means "big fire." Going to investigate the crater and perhaps slay Lavos at the beginning of his life-cycle, the party discovers that he has already burrowed too deep into the earth to pursue. He has left a gate in his wake, however. The party uses the new gate and finds itself in a cave in B.C. 12,000. Outside, the lush green of 65,000,000 has been replaced by a featureless plain of snow.

Comments

Magus' Castle

Magus' Castle is one of Chrono Trigger's most memorable sections and serves a very interesting purpose in the game. The castle's motif of death makes it a rare confrontation with darkness in a game that maintains a mostly-lighthearted tone. Yet, the equally-strong motif of illusion (and the game's later revelations) make the castle's meaning more ambiguous. In some sense, it is a confrontation with evil. Yet the story of the brave hero vanquishing the evil wizard is very misleading here, and the game continually reminds us that things are not as they seem.

The whole castle is haunted by death. Seemingly human beings transform into undead creatures; monstrous overseers watch as skeletons attack each other in futile battle; Magus hears the Black Wind, the game's recurring symbol for impending death; and Magus and his three generals all remind Glenn of Cyrus' death, which hangs over all the events in the castle as a spur to vengeance and as a reminder that courage and heroism can't stave off the void. Despite the occult trappings and Magus' position as leader of the Mystics (Demons, in the original Japanese), the portrayal of death here evokes the reaper rather than the devil. Death is a grim and inevitable extension of life. The two sets of skeletons sum it up; one group is forced to dance in celebration of Lavos (who represents total obliteration) while the other skeletons fight endlessly among themselves, seemingly oblivious to the fact that they are already dead. Death mocks the living and strips them of their individuality, as in the medieval danse macabre. Human behavior, even the noble human behavior of a hero like Cyrus, leads inevitably to the indifferent grave. What's the function of this portrayal narratively, and what does it say about the game's stance on death?

The death motif can only be understood in light of the illusion motif. The meta-game manipulation of save points, the illusions of the party's loved ones and even Flea's false appearance of femininity all lead the player (not the characters, but the player) to suspect deception, which turns out to be exactly what's afoot. The deception is twofold. On a narrative level, the player discovers the Magus did not create Lavos. The evil wizard, who would be the ultimate villain in a more conventional game, is replaced as antagonist by an amoral and seemingly invincible force for destruction. This narrative bait-and-switch ends the clichéd sword-and-sorcery arc and reveals the true stance on evil and death that lies beneath the surface of that pastiche. Just as Lavos is revealed to be something much older and more powerful than a mere villain, death is revealed to be a force far beyond the reach of our facile stories of good and evil. This is the second deception, this one meta-narrative rather than narrative. We as players have been fooled into believing in a myth of good versus evil that turns out to be false in almost every respect. As I discussed last time, Frog is anything but the Destined Hero of myth and fantasy cliché. We are beginning to find that Magus is not what we thought he was either and that the trappings of evil are equally as artificial as the trappings of heroism that Frog needed -- psychologically -- to confront Magus. It's all a pose, from Slash's voluntary adherence to Magus' law to Flea's cutesy-girl act to Magus' (as-yet undiscovered) fraud.

In the midst of all this illusion, there are two undeniable truths that move the plot forward. First, that in Frog's hands the Masamune is mysteriously powerful enough to harm Magus, despite its failure to do so when wielded by Cyrus. Magus asks Frog, "W...what have you done to the Masamune...?" A complete discussion of the Masamune's power will have to wait for a later article, but it suffices for now to point out that Masa and Mune themselves identified the Masamune's most important source of power as the purpose to which it is put. It is what Frog is doing when he assaults Magus, not just the blade he is using, that can pierce all of Magus' magic. Frog is beginning to discover the secret weapon that can cut through all the illusions of the castle and through death itself. That weapon is authenticity.

The second undeniable truth of Magus' Castle is Lavos. When Lavos is awakened at the end of the battle, he tears time itself apart, creating an impossibly huge gate and scattering both the heroes and the villain across time. This scene calls to mind Rumi's poem about Solomon and the Gnats. It is a fitting capstone to this subversion of the Hero's Journey that when the heroes and the villain finally reach the metaphysical power they have been fighting over, their little morality play is swept away indiscriminately in the face of reality. Though everything else in this story arc is somehow false, the power of Lavos -- the implacable power of time and truth -- is real.

65,000,000 BC and the Defeat of Azala

With the fall of the reptites and the appearance of Lavos in place, we can properly analyze the time period of 65,000,000. It is a fairly conventional "caveman era," but it holds special interest for an existentialist reading because it portrays the roots of humanity, the beginning of humanity's struggle against the void (represented by Lavos), and the collapse of a civilization.

The reptites, especially Azala, are interesting antagonists because they are not really evil. We are encouraged to view the competition between the humans and the reptites as an ecological struggle, not a moral one, and in terms of Darwinian fitness the reptites seem to be the rightful winners of the battle. They are smarter, tougher and more "civilized" than the humans, to be sure. The Laruba Tribe takes this position and chooses to hide from the reptites. Ayla, in contrast, recognizes that conflict is the only path to survival: "Win and live. Lose and Die. Rule of life. No change rule." This statement seems simple (and the caveman-talk doesn't help) but actually sums up the thematic climate of 65,000,000 very nicely. Victory and domination are not just means to survival, but they are survival. The Laruba are portrayed in the game as cowardly and endlessly willing to absorb punishment rather than risking battle. This negative portrayal seems to sanction Ayla's view that surviving alongside the reptites is impossible. The only way for one species to live is to kill the other. Note too that this conflict is not set up by either species, but by nature itself. It is the "rule of life." It is by the light of this radical idea that we must read the tragic defeat of Azala.

Azala is for the reptites what Ayla is for the humans. Just as Ayla is the epitome of savage strength, Azala is the epitome of advanced civilization: smart, ruthless and society-minded. And while Ayla seems prophetic in her insistence that humans will take possession of the earth, Azala shows a prescient suspicion that the reptites are doomed. Yet, Azala too recognizes the "rule of life" and fights to the end. Like the personal struggles of existentialism, which cannot ultimately be "won, the reptites' struggle is one that would be nonsensical to abandon even in the face of certain annihilation. People cannot escape death by giving up their struggle against it, and neither can civilizations. It is key to understand that the game commends both Ayla and Azala for fighting the final battle as representatives of their respective species because they are both fighting against death, as symbolized by the red star that hangs over their battle. The message, I believe, is that while death cannot be overcome, the struggle against it is a defining fact of life, and cannot be evaded or ignored. We may turn to the Theater of the Absurd for a similar view of death; there, life and death coexist in irrational but real harmony, and attempts to reconcile them logically are doomed. It is as though two separate realities exist, one of life and one of death, and that the passage between them is as inexplicable as it is inevitable because the logic of life does not apply to death. The two species of 65,000,000 demonstrate this gulf aptly. The fall of the reptites is the end of a civilization that is featured only peripherally in the game, but is presumably as vast and advanced as human civilization will become. Though the stories of those civilizations intersect briefly, the logic of one story cannot apply to the other, and the vast stretch of time ruled by humanity is only an unsettling blank from Azala's --perfectly valid! -- perspective. As Azala says of the Reptites, "We have no future." This is, in some sense, the heart of the existential struggle; the fact that death and the void, though "merely" objective, can cross into our subjective existences, dissolving the personal worlds that we all build and inhabit. The fall of the reptites is the death of a meta-narrative and (in combination with the descent of Lavos) the birth of another.

Lavos, part 1

It is only after Azala's defeat (about halfway through the game!) that the player understands the nature of Lavos, and there are still surprises in store. Let's review what we know about Lavos so far:

Lavos is a giant monster who fell from space in 65,000,000 B.C. His impact formed a huge crater and cast the earth into an ice age. Since then, Lavos has drained energy from the planet and grown ever-stronger. In 2300 A.D. he erupts from the earth and ravages the surface of the planet, destroying civilization and nearly wiping out humanity.

Up until this middle section of the game, Lavos seems just like any other video game monster. It is only with the revelation of his history that he becomes something more like a cthuloid horror or a force of nature. This is a key transformation because the drastic change to the "antagonist" recasts the game's heroes. Up until now, Crono and his allies have been heroes in the traditional sense, as epitomized by their fight against Magus. After bearing witness to Lavos' descent and discovering his insidious power, they learn that their enemy represents total negation, not evil. Unlike the classic hero, who struggles to return the world to a lost equilibrium, the heroes of Chrono Trigger are trying to stop or reverse a process that dates from the beginning of human civilization -- and, to some degree, defines it.

Lavos has been attacked as something of a generic villain, which I think is a misunderstanding. He is not really a villain; he is a fact. As such, he's not akin to his contemporaries in other Squaresoft games, like Sephiroth and Kefka. Lavos is linked most obviously to Lovecraft's Great Old Ones, but also possesses something of the consuming negativity of the dead God of Nietzsche. Ultimately, he acts as an incarnation of the abstract menaces of Chrono Trigger, Time and Death. Like those forces, Lavos's brand of destruction is as meaningless as it is virulent. In both 65,000,000 and 1999, Lavos utterly destroys a whole civilization for no reason, denying them even the final consolation of making sense of their own demise. The world of 2300 makes it clear that Lavos leaves only oblivion in his wake, and this too is a substantial contrast to the classic villain, who seeks to instate a new order or at least to improve his own state. In further parallel to Time and Death, Lavos is a disaster endemic to human existence. Because Lavos fell at the dawn of human civilization -- and in fact created the ice age that permitted humanity to become the planet's dominant species -- the whole of human history takes place in the shadow of his mindless, ravenous oblivion. As Beckett puts it, "the gravedigger puts on the forceps."

Lavos is a symbol of death, nothingness and time's unstoppable flight toward decay. In this light, the struggle against Lavos is one with clear existentialist antecedents. Nietzsche's dual obsession with God's nonexistence and His corrupting influence on humanity mirrors the fight against Lavos, who is physically and historically central to the human world and yet ultimately obliterates it. One might also compare Lavos to Death in Bergman's The Seventh Seal, insofar as he is an amoral force for destruction that ultimately dissolves all individuality and meaning... or to Godot in "Waiting for Godot," who is the teleological void that dooms the attempts of Gogo and Didi to establish any meaning or reason. I don't mean to say that these existentialist works are all perfectly analogous, only that they are variations on the theme of the empty center, the void that supports the structure of the human world, yet must finally negate it from the inside out.

There's a lot left to say about Lavos, but it can wait for later posts, after the game reveals strange new sides of him. It suffices for now to establish that he is one of the keystones of the existentialist reading of Chrono Trigger. If Lavos represents the unreasoning destructive power of Time and Death, then the overarching fight to rescue the planet from his hunger is an existentialist struggle to salvage meaning from nothingness. One can read almost the whole game in this light.

Next Time: Life, Time, Reason and the transcendence of Dreamstone

But First (Maybe): Elves, elv