Chrono Trigger: An Existentialist Reading (Part II)

Time for more of my existentialist reading of Chrono Trigger. This one is where we really start to see clear existentialist themes, as well as tricks of form that connect those themes to the video game medium.

Synopsis, Part Two

Crono is forced to appear in a (beautifully illustrated) courtroom to stand trial for abducting the Princess. Brief arguments are made, evidence is produced, and Crono may be found guilty or not guilty depending upon the player's earlier actions (more on this later). If guilty, Crono is sentenced to death. If not guilty, he is sentenced to only three days in jail, but the Chancellor tells the jailer that the sentence was death. In either case, Crono is confined to a cell and told that he is three days from execution.

When three days have elapsed, Crono is led to a guillotine but is rescued at the last moment by Lucca, who has broken into the jail to free him. Together Lucca and Crono escape the dungeon after fighting the Dragon Tank, an experimental dragon-shaped machine that guards the passage from the jail to the castle (Note the sense of anachronism in a tank defending a castle, especially in 1000 A.D. -- this goes again to the conflict between society's self-image and its transformation by technology, a conflict that is a historical root of existentialism). In the castle proper, Lucca and Crono are surrounded by guards. Marle, wearing her dress and acting as Princess Nadia, demands that the guards stand down. First the Chancellor and then the King himself intervene, telling Nadia that she must put her title before herself. Marle throws off her dress, revealing her usual "Marle" outfit and runs away with Crono and Lucca. (Note Marle's failure to integrate her identity here, symbolized by the costume change; she has two discrete identities and must switch between them as the situation demands). The three find a time gate in the forest outside of Guardia Castle. They take it to escape the guards, unaware of where it will lead.

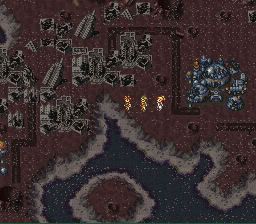

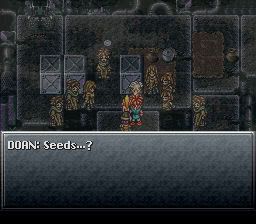

Crono, Lucca and Marle find themselves in a strange, futuristic structure. Lucca ironically comments that the civilization seems "advanced," but when the party steps outside, a post-apocalyptic wasteland is revealed; the world-map is a blasted landscape of ruined cities, falling snow and a few domed structures. The party discovers that it has reached 2300 A.D.. They eventually arrive at a former Info Center that sits atop a food storage facility and an information computer. The party fights past a robot guard to enter the food storage facility, hoping to find food for the dome's inhabitants, but finds that the refrigeration has failed and only a few viable seeds remain. They use the information computer to find a time gate that can take them home; they locate it in Proto Dome. They also accidentally view footage of a disaster called "The Day of Lavos" in 1999, in which a huge creature erupted from the earth and laid waste to everything around him. It was apparently this disaster that caused the grim future. Marle suggests that the three use time travel to prevent this disaster from occurring, and Crono and Lucca agree.

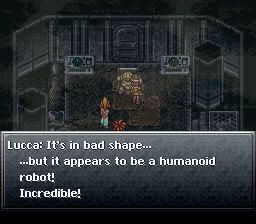

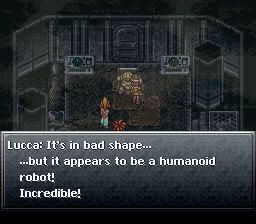

After giving the seeds to the inhabitants of the dome, the party travels to Proto Dome and finds a broken robot there. Lucca repairs the robot, assuring the group that machines cannot be evil and that she can make sure it won't hurt them. When the robot awakens, it informs the party that they will need to reactivate a generator in a nearby factory to open the sealed door that lies between them and the time gate. The party (now including the newly-christened Robo) travels to the factory to do so.

After reactivating the power, Robo is assaulted by his former brothers, a number of identical robots with serial numbers consecutive with Robo's original name, R66-Y. Though Robo is happy to see them, they attack, claiming that his original purpose and theirs is to stop human intruders and that he is malfunctioning. Robo does not fight back as they destroy him. The remainder of the party defeats the robots after the assault and drags the broken Robo back to Proto Dome, where Lucca repairs him again. When he has been fixed, Robo volunteers to travel with the party to help prevent The Day of Lavos. The party uses the time gate, but something goes wrong.

The party finds itself on a weird platform surrounded by fog and inhabited by one dozing man in a robe. When he awakens, he tells them that they have reached the End of Time by trying to travel through a gate in a group larger than three. The End of Time, he explains, links to every time gate that the party has used and also to The Day of Lavos itself. Because only three people can use a gate at once, at least one of the four must remain behind; this is simply a device to explain why a party cannot exceed three members, which is a common limitation in console RPGs. Before the party leaves, the Old Man advises them to meet the other inhabitant of the End of Time and directs them through the platform's only door.

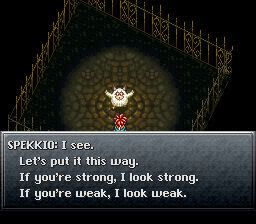

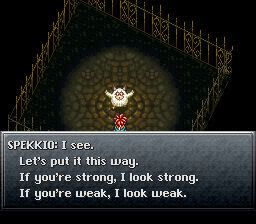

The creature behind the door is Spekkio, the God of War. Spekkio appears as a weak monster, but claims that this is only because the party is weak. He explains that all of reality is based upon four forces: Shadow, Lightning, Air and Water. He identifies the innate element of each party member and grants them corresponding magic power. He explains that long ago, all people were able to use magic, but that it is now a special gift because it got out of hand. He cannot grant magic to Robo, but tells him that his built-in weaponry will suffice.

The Old Man, satisfied with the new power granted to the party, advises them to return to their own time before going any farther in their quest. They depart for 1000 A.D.

Comments

The Trial

Crono's trial is an example of the unmistakable and clearly intentional medium-manipulation that the Chrono Trigger design team employed. The design team (known as the "Dream Team") consisted of seasoned veterans at RPG design. As a result of their experience and their sense of creating a for-the-fans work, they manipulated the fantasy RPG genre and the video game medium both satirically and to emphasize the game's meaning on a meta-game level.

When the trial begins, the Chancellor remarks of Crono that "you, the jury, shall decide his fate." This is subtle irony, because when the trial gets underway the player is surprised to find that seemingly meaningless "extras" from the Millennial Fair scene are called to testify about Crono's behavior there, and that this testimony determines Crono's guilt or innocence. His fate, at least in terms of the sentence he will receive, depends entirely upon the player's own earlier actions. For example, just before going to look at Lucca's telepod at the Millennial Fair, Marle wants to stop and buy candy at a stand. The player, as Crono, can try to pull her away from this activity, but she will always insist on going back until a certain length of time has passed. This mechanical response leads the player to believe that there are no consequences for pulling Marle away repeatedly, just for fun. This comes up at the trial, though; if Crono is seen pulling Marle around, it contributes to the jury finding him guilty of abduction. The surprise factor here would be easily missed by a critic unfamiliar with video games. In console RPGs, the game world's response to the player's actions is typically very limited and mechanical. There are certain key decisions that advance the plot, and these are usually clearly defined as such. Other events and characters are mere filler and don't react to the player's experience of the game.

Players understand the convention of limited interactivity. So when bit characters show up to testify about "privileged" behavior, behavior that the player feels confident is separate from the diegetic world, it creates a humorous and interesting tension. A similar technique is used in 2300 A.D. when the players encounter Johnny (a minor event omitted from the synopsis above). Robots surround the party and the game's distinctive battle music starts, fooling the player into believing that a fight will ensue... until Johnny arrives moments later and cools tensions. Without the music cue, the player would not be taken in by the situation as the characters are supposed to be, but the use of a non-diegetic game element suckers us into it. This is because we are trained to trust that non-diegetic elements pertain only to the player's experience of the game, while diegetic elements pertain to the characters. Like Crono's perpetual silence, these techniques serve to blur the player/character distinction. They also underline the game's theme of choice. They remind us that actions have consequences in this world and that our immediate play-experience, far from being walled off from the world of the narrative, both affects and is affected by it.

2300 A.D. and the Seeds

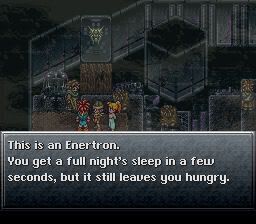

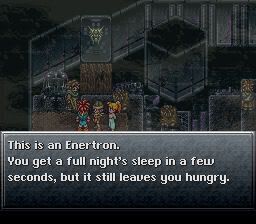

2300 A.D. is the third time period to which we are introduced and represents our only vision of the future (relative to Crono's home period of 1000 A.D., which we are to take as the game's "present"). As a post-apocalyptic world that shows us the horror we are trying to prevent for the rest of the game, 2300 contains the game's most directly condemnatory satire. The most interesting feature of the future in existentialist terms is the Enertron. The Enertron is the device that keeps the last remains of human civilization alive in a world that is without edible food. To use it, the characters cram into a metal sphere. Within moments, they are restored to full HP and MP; however, a distinctive sound effect plays and a caption appears that reads, "But you're still hungry...."

The clear implication is that the pathetic remnants of humanity exist in perpetual, crushing starvation that is made even more torturous by a machine that can keep them alive -- but hungry -- indefinitely. Why choose this haunting dystopia and not another? For the designers of Chrono Trigger, dystopia could not simply be a descent to savagery or war, because those elements are present in other times (and genres). Instead, they had to stretch to find a more dire and distinct future. They came up with total stagnation. In 2300, humanity is adrift in a bubble of its own technology, literally stranded within domes that defend against the ruined natural world. Humans have lost all connection to hope and to the future; instead, they rely abjectly on an artifact of the past that sustains them biologically but leaves them empty of all that human existence should be.

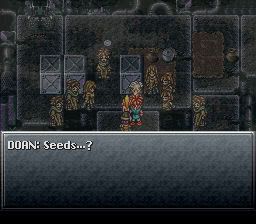

The underlying assumption in this scenario is that neither technology nor biology is sufficient for truly human existence, a subtle but bold statement that arises once again from the fusion of popular genres in Chrono Trigger. The seeds that the party retrieves for Doan are symbols of hope for humanity to regain itself even after the apocalypse. Seeds are recurring symbols in Chrono Trigger, and rightly so, because they neatly encapsulate the ingredients that the game posits as vital to human life: potentiality and harmony with the planet. Whenever humanity stagnates or loses touch with the planet (nature, yes, but also the "given world" of experience), it becomes something less than human. A seed is necessary to reconnect to the planet and to the future.

It is important to keep this formulation in mind in an existentialist reading of the game, because it essentially supports the idea of human existence as defined by choice and consciousness, but paints humanity in a slightly more collective shade than typical existentialism. We might compare Chrono Trigger's implicit view of human existence with Taoism or with Heidegger's indivisible Dasein. As the game progresses, we will see clearly that while the potentiality of the individual is primary in Chrono Trigger, that potentiality is inextricable from its connection to time and, via time, to other humans. That is, the personal, conscious and free experience of the World is the hidden order of that World, and in fact is that World. This is one of the few philosophical points made explicit in the text of the game, as we will see in later articles.

Robo

Crono is an Existential Hero, but in a purely formal sense. He is what he is because he acts as the player's surrogate. To find an Existential Hero who exists wholly within the game world, we need look no further than Robo. It is worth transcribing Robo's whole introduction to the party here, because it is one of the most clear and dense expositions of existentialist themes in the game:

Lucca: It's in bad shape...but it appears to be a humanoid robot! Incredible! ... I think I can fix it.

Marle: What?! It might attack us!

Lucca: I'll make sure it won't. Machines aren't capable of evil... humans make them that way.

Marle: Lucca, you...pity them don't you?

Lucca: Let me get to work now, okay?

Lucca: Right, that does it! I'm going to give it some juice!

ROBOT: ......

Marle: Good morning!

ROBOT: Mo...... Good morning, mistress. What is your command?

Marle: I'm not your «mistress.» I'm Marle! ...and this is Crono... and Lucca, here, fixed you!

ROBOT: Understood. Madam Lucca fixed me.

Lucca: Just Lucca will do.

ROBOT: Impossible. That would be rude.

Lucca: Look, I hate formal titles! Don't you, Marle?

Marle: Hate 'em!

ROBOT: I understand, Lucca.

Lucca: All right! Now what's your name?

ROBOT: Name? Ah, my serial number. It is R66-Y.

Lucca: R66-Y? Cool!

Marle: No! That won't do at all!

Marle: Come on Crono, let's give him a better name!

(Here the player inputs a new name, with Robo as the default.)

Marle: Robo... Robo...that's perfect! Your new name is Robo, okay?

ROBOT: I am... Robo. Data storage complete.

Note the return of the false name motif. Like Marle, Robo takes on a new name to join the party. As we learn in the factory, R66-Y was a serial number that defined Robo in relation to his robot brothers. In the same scene, we discover that Robo's brothers now consider him to be malfunctioning. He has lost both his place in their ranks and his original programming, as symbolized by his name change. Like Marle, Robo suffers an identity crisis. In Robo's case, he has lost his old, strictly defined self and is now left to create the identity of Robo without guidance; his new "masters" demand nothing from him and reject his attempts to defer to them with lofty titles. Robo's distress at his situation is clear when he refuses help as his former brothers destroy him. He will neither betray who he was nor who he is, with the result that he must submit to his own obliteration. His salvation is heralded by the power of choice.

When Robo is repaired in Proto Dome, Lucca asks Robo what he plans to do once he's repaired. He responds, "What am I...going to do? [...] Lucca, no one has ever asked me that before!" Robo is discovering that although his world and both of his names are given, his identity is not, because he has the capacity and responsibility of choice. His "malfunction" crippled him in the factory only because he accepted all departures from his programming as flaws. Now, Robo begins to see that they represent potential instead. Robo chooses to help in the fight to prevent the Day of Lavos. Much later in the game it is commented that if Robo is successful in preventing that disaster, he will wipe out his own history and perhaps end his own existence. This adds an element of pathos to Robo's story and comments on humanity's relationship to the implacable forces of death and time. Robo, by exercising choice, both embraces and defies death. He accepts the threat of destruction, and this frees him to exercise his will on history that would otherwise lie behind him instead of ahead. Nietzsche wrote:

"To redeem what is past and remold every 'It was' into 'I willed it so!' -- only that would I call redemption!"

Robo's strange, posthumous redemption will be to remold "You were not" into "I willed it so."

The End of Time

The End of Time is a noticeable departure from other elements of Chrono Trigger. It is not a clear pastiche of any existing genre, nor is its significance in the grand sweep of time revealed. On the simplest level, The End of Time is a sort of home base that serves numerous utilitarian functions in the game. It makes time travel more manageable during a large chunk of the game, gives Spekkio a place to exist, serves as an explanation for why the whole party can't travel together, and generally helps gameplay to proceed smoothly. Nonetheless, its specific form can't be overlooked.

The End of Time shows no signs of disorder or destruction, though a single platform in the void seems to be all that is left of the world. The brickwork, fence and single lamppost at the End of Time convey a serene and civilized -- if somewhat incongruous -- image of history's end. Furthermore, the End of Time is presented as a static location, not as an event. That time's end is taken for granted and used as a home base of sorts in Chrono Trigger is meaningful; note that it implicitly dismisses any number of end-of-the-world mythologies while simultaneously satirizing its own materialist position through the placement of an old-fashioned lamppost as the only light left in the universe. Because we are supposed to believe in so many different time periods and genres throughout the game, from a medieval war against demons to a robot-dominated future, the end of time cannot be one that reveals some transcendent meaning, because that would invalidate some of the era-specific struggles we are supposed to care about. For this reason, we get a minimalist End of Time that refuses to pass judgment on the past, to redeem it, or even to contextualize it. Unlike traditional afterlives in which justice is rewarded and evil is punished, the End of Time is simply an empty stadium after the big game. The struggles of humanity are over, and we find that their meaning must be in living them, not in any omnipotent and morally-charged retrospection.

Time is not literally cyclical in Chrono Trigger, yet the End of Time reminds me of Sisyphus' moment of accomplishment in Camus, the moment when his punishment (the rock rolling downhill once again) earns him a brief respite from his absurd toil. Though Camus' radical meaninglessness has no place in Chrono Trigger, his sense of rebellious lust for life in the face of absurdity does. The End of Time marks the final boundary of humanity's domain, but this boundary affirms what lies within it; it refutes the idea that altering history is somehow hubris by highlighting the lack of a outside authority to whom Crono might justify his actions. Potentiality, which is dead in 2300, is most alive at the End of Time, where the book of history lies open, the magic that can rewrite it is discovered, and the void gives humans implicit authority to do as they will.

Spekkio

What is significant about Spekkio is what he is not: a deity in the Western sense. The self-described "God of War" does not intervene in the events of the plot, has no particular moral authority, and is not omnipotent. Notably, he cannot grant magic to Robo (nor, later, to Ayla) because neither one is descended from humanity's magic-using ancestors; Spekkio is not even the source of magic, then, but only has the power to awaken it. The casual introduction of a god as comic relief shows that the game's designers bring a distinctively Japanese non-theocentric worldview to the game. Yeah, there's a God of War. So what? He is just another strange character in a game that has more than its share. His existence no more defines the meaning of the game-world than does the existence of lizard men, wizards and golems. The profound "God is Dead" message of Nietzsche more properly applies to Lavos than to Spekkio. Spekkio represents, rather, an off-hand dismissal of Voltaire's claim that "if God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him." The game's position seems to be that our problems are of the sort no god can solve, and that even finding a god (as Crono does) does not resolve the issues at hand.

Next time: The Gaze of the Hero legend, the supremacy of will, and Ayla the Ubermensch

But first: Elves, Elves, Elves!

Synopsis, Part Two

Crono is forced to appear in a (beautifully illustrated) courtroom to stand trial for abducting the Princess. Brief arguments are made, evidence is produced, and Crono may be found guilty or not guilty depending upon the player's earlier actions (more on this later). If guilty, Crono is sentenced to death. If not guilty, he is sentenced to only three days in jail, but the Chancellor tells the jailer that the sentence was death. In either case, Crono is confined to a cell and told that he is three days from execution.

When three days have elapsed, Crono is led to a guillotine but is rescued at the last moment by Lucca, who has broken into the jail to free him. Together Lucca and Crono escape the dungeon after fighting the Dragon Tank, an experimental dragon-shaped machine that guards the passage from the jail to the castle (Note the sense of anachronism in a tank defending a castle, especially in 1000 A.D. -- this goes again to the conflict between society's self-image and its transformation by technology, a conflict that is a historical root of existentialism). In the castle proper, Lucca and Crono are surrounded by guards. Marle, wearing her dress and acting as Princess Nadia, demands that the guards stand down. First the Chancellor and then the King himself intervene, telling Nadia that she must put her title before herself. Marle throws off her dress, revealing her usual "Marle" outfit and runs away with Crono and Lucca. (Note Marle's failure to integrate her identity here, symbolized by the costume change; she has two discrete identities and must switch between them as the situation demands). The three find a time gate in the forest outside of Guardia Castle. They take it to escape the guards, unaware of where it will lead.

Crono, Lucca and Marle find themselves in a strange, futuristic structure. Lucca ironically comments that the civilization seems "advanced," but when the party steps outside, a post-apocalyptic wasteland is revealed; the world-map is a blasted landscape of ruined cities, falling snow and a few domed structures. The party discovers that it has reached 2300 A.D.. They eventually arrive at a former Info Center that sits atop a food storage facility and an information computer. The party fights past a robot guard to enter the food storage facility, hoping to find food for the dome's inhabitants, but finds that the refrigeration has failed and only a few viable seeds remain. They use the information computer to find a time gate that can take them home; they locate it in Proto Dome. They also accidentally view footage of a disaster called "The Day of Lavos" in 1999, in which a huge creature erupted from the earth and laid waste to everything around him. It was apparently this disaster that caused the grim future. Marle suggests that the three use time travel to prevent this disaster from occurring, and Crono and Lucca agree.

After giving the seeds to the inhabitants of the dome, the party travels to Proto Dome and finds a broken robot there. Lucca repairs the robot, assuring the group that machines cannot be evil and that she can make sure it won't hurt them. When the robot awakens, it informs the party that they will need to reactivate a generator in a nearby factory to open the sealed door that lies between them and the time gate. The party (now including the newly-christened Robo) travels to the factory to do so.

After reactivating the power, Robo is assaulted by his former brothers, a number of identical robots with serial numbers consecutive with Robo's original name, R66-Y. Though Robo is happy to see them, they attack, claiming that his original purpose and theirs is to stop human intruders and that he is malfunctioning. Robo does not fight back as they destroy him. The remainder of the party defeats the robots after the assault and drags the broken Robo back to Proto Dome, where Lucca repairs him again. When he has been fixed, Robo volunteers to travel with the party to help prevent The Day of Lavos. The party uses the time gate, but something goes wrong.

The party finds itself on a weird platform surrounded by fog and inhabited by one dozing man in a robe. When he awakens, he tells them that they have reached the End of Time by trying to travel through a gate in a group larger than three. The End of Time, he explains, links to every time gate that the party has used and also to The Day of Lavos itself. Because only three people can use a gate at once, at least one of the four must remain behind; this is simply a device to explain why a party cannot exceed three members, which is a common limitation in console RPGs. Before the party leaves, the Old Man advises them to meet the other inhabitant of the End of Time and directs them through the platform's only door.

The creature behind the door is Spekkio, the God of War. Spekkio appears as a weak monster, but claims that this is only because the party is weak. He explains that all of reality is based upon four forces: Shadow, Lightning, Air and Water. He identifies the innate element of each party member and grants them corresponding magic power. He explains that long ago, all people were able to use magic, but that it is now a special gift because it got out of hand. He cannot grant magic to Robo, but tells him that his built-in weaponry will suffice.

The Old Man, satisfied with the new power granted to the party, advises them to return to their own time before going any farther in their quest. They depart for 1000 A.D.

Comments

The Trial

Crono's trial is an example of the unmistakable and clearly intentional medium-manipulation that the Chrono Trigger design team employed. The design team (known as the "Dream Team") consisted of seasoned veterans at RPG design. As a result of their experience and their sense of creating a for-the-fans work, they manipulated the fantasy RPG genre and the video game medium both satirically and to emphasize the game's meaning on a meta-game level.

When the trial begins, the Chancellor remarks of Crono that "you, the jury, shall decide his fate." This is subtle irony, because when the trial gets underway the player is surprised to find that seemingly meaningless "extras" from the Millennial Fair scene are called to testify about Crono's behavior there, and that this testimony determines Crono's guilt or innocence. His fate, at least in terms of the sentence he will receive, depends entirely upon the player's own earlier actions. For example, just before going to look at Lucca's telepod at the Millennial Fair, Marle wants to stop and buy candy at a stand. The player, as Crono, can try to pull her away from this activity, but she will always insist on going back until a certain length of time has passed. This mechanical response leads the player to believe that there are no consequences for pulling Marle away repeatedly, just for fun. This comes up at the trial, though; if Crono is seen pulling Marle around, it contributes to the jury finding him guilty of abduction. The surprise factor here would be easily missed by a critic unfamiliar with video games. In console RPGs, the game world's response to the player's actions is typically very limited and mechanical. There are certain key decisions that advance the plot, and these are usually clearly defined as such. Other events and characters are mere filler and don't react to the player's experience of the game.

Players understand the convention of limited interactivity. So when bit characters show up to testify about "privileged" behavior, behavior that the player feels confident is separate from the diegetic world, it creates a humorous and interesting tension. A similar technique is used in 2300 A.D. when the players encounter Johnny (a minor event omitted from the synopsis above). Robots surround the party and the game's distinctive battle music starts, fooling the player into believing that a fight will ensue... until Johnny arrives moments later and cools tensions. Without the music cue, the player would not be taken in by the situation as the characters are supposed to be, but the use of a non-diegetic game element suckers us into it. This is because we are trained to trust that non-diegetic elements pertain only to the player's experience of the game, while diegetic elements pertain to the characters. Like Crono's perpetual silence, these techniques serve to blur the player/character distinction. They also underline the game's theme of choice. They remind us that actions have consequences in this world and that our immediate play-experience, far from being walled off from the world of the narrative, both affects and is affected by it.

2300 A.D. and the Seeds

2300 A.D. is the third time period to which we are introduced and represents our only vision of the future (relative to Crono's home period of 1000 A.D., which we are to take as the game's "present"). As a post-apocalyptic world that shows us the horror we are trying to prevent for the rest of the game, 2300 contains the game's most directly condemnatory satire. The most interesting feature of the future in existentialist terms is the Enertron. The Enertron is the device that keeps the last remains of human civilization alive in a world that is without edible food. To use it, the characters cram into a metal sphere. Within moments, they are restored to full HP and MP; however, a distinctive sound effect plays and a caption appears that reads, "But you're still hungry...."

The clear implication is that the pathetic remnants of humanity exist in perpetual, crushing starvation that is made even more torturous by a machine that can keep them alive -- but hungry -- indefinitely. Why choose this haunting dystopia and not another? For the designers of Chrono Trigger, dystopia could not simply be a descent to savagery or war, because those elements are present in other times (and genres). Instead, they had to stretch to find a more dire and distinct future. They came up with total stagnation. In 2300, humanity is adrift in a bubble of its own technology, literally stranded within domes that defend against the ruined natural world. Humans have lost all connection to hope and to the future; instead, they rely abjectly on an artifact of the past that sustains them biologically but leaves them empty of all that human existence should be.

The underlying assumption in this scenario is that neither technology nor biology is sufficient for truly human existence, a subtle but bold statement that arises once again from the fusion of popular genres in Chrono Trigger. The seeds that the party retrieves for Doan are symbols of hope for humanity to regain itself even after the apocalypse. Seeds are recurring symbols in Chrono Trigger, and rightly so, because they neatly encapsulate the ingredients that the game posits as vital to human life: potentiality and harmony with the planet. Whenever humanity stagnates or loses touch with the planet (nature, yes, but also the "given world" of experience), it becomes something less than human. A seed is necessary to reconnect to the planet and to the future.

It is important to keep this formulation in mind in an existentialist reading of the game, because it essentially supports the idea of human existence as defined by choice and consciousness, but paints humanity in a slightly more collective shade than typical existentialism. We might compare Chrono Trigger's implicit view of human existence with Taoism or with Heidegger's indivisible Dasein. As the game progresses, we will see clearly that while the potentiality of the individual is primary in Chrono Trigger, that potentiality is inextricable from its connection to time and, via time, to other humans. That is, the personal, conscious and free experience of the World is the hidden order of that World, and in fact is that World. This is one of the few philosophical points made explicit in the text of the game, as we will see in later articles.

Robo

Crono is an Existential Hero, but in a purely formal sense. He is what he is because he acts as the player's surrogate. To find an Existential Hero who exists wholly within the game world, we need look no further than Robo. It is worth transcribing Robo's whole introduction to the party here, because it is one of the most clear and dense expositions of existentialist themes in the game:

Lucca: It's in bad shape...but it appears to be a humanoid robot! Incredible! ... I think I can fix it.

Marle: What?! It might attack us!

Lucca: I'll make sure it won't. Machines aren't capable of evil... humans make them that way.

Marle: Lucca, you...pity them don't you?

Lucca: Let me get to work now, okay?

Lucca: Right, that does it! I'm going to give it some juice!

ROBOT: ......

Marle: Good morning!

ROBOT: Mo...... Good morning, mistress. What is your command?

Marle: I'm not your «mistress.» I'm Marle! ...and this is Crono... and Lucca, here, fixed you!

ROBOT: Understood. Madam Lucca fixed me.

Lucca: Just Lucca will do.

ROBOT: Impossible. That would be rude.

Lucca: Look, I hate formal titles! Don't you, Marle?

Marle: Hate 'em!

ROBOT: I understand, Lucca.

Lucca: All right! Now what's your name?

ROBOT: Name? Ah, my serial number. It is R66-Y.

Lucca: R66-Y? Cool!

Marle: No! That won't do at all!

Marle: Come on Crono, let's give him a better name!

(Here the player inputs a new name, with Robo as the default.)

Marle: Robo... Robo...that's perfect! Your new name is Robo, okay?

ROBOT: I am... Robo. Data storage complete.

Note the return of the false name motif. Like Marle, Robo takes on a new name to join the party. As we learn in the factory, R66-Y was a serial number that defined Robo in relation to his robot brothers. In the same scene, we discover that Robo's brothers now consider him to be malfunctioning. He has lost both his place in their ranks and his original programming, as symbolized by his name change. Like Marle, Robo suffers an identity crisis. In Robo's case, he has lost his old, strictly defined self and is now left to create the identity of Robo without guidance; his new "masters" demand nothing from him and reject his attempts to defer to them with lofty titles. Robo's distress at his situation is clear when he refuses help as his former brothers destroy him. He will neither betray who he was nor who he is, with the result that he must submit to his own obliteration. His salvation is heralded by the power of choice.

When Robo is repaired in Proto Dome, Lucca asks Robo what he plans to do once he's repaired. He responds, "What am I...going to do? [...] Lucca, no one has ever asked me that before!" Robo is discovering that although his world and both of his names are given, his identity is not, because he has the capacity and responsibility of choice. His "malfunction" crippled him in the factory only because he accepted all departures from his programming as flaws. Now, Robo begins to see that they represent potential instead. Robo chooses to help in the fight to prevent the Day of Lavos. Much later in the game it is commented that if Robo is successful in preventing that disaster, he will wipe out his own history and perhaps end his own existence. This adds an element of pathos to Robo's story and comments on humanity's relationship to the implacable forces of death and time. Robo, by exercising choice, both embraces and defies death. He accepts the threat of destruction, and this frees him to exercise his will on history that would otherwise lie behind him instead of ahead. Nietzsche wrote:

"To redeem what is past and remold every 'It was' into 'I willed it so!' -- only that would I call redemption!"

Robo's strange, posthumous redemption will be to remold "You were not" into "I willed it so."

The End of Time

The End of Time is a noticeable departure from other elements of Chrono Trigger. It is not a clear pastiche of any existing genre, nor is its significance in the grand sweep of time revealed. On the simplest level, The End of Time is a sort of home base that serves numerous utilitarian functions in the game. It makes time travel more manageable during a large chunk of the game, gives Spekkio a place to exist, serves as an explanation for why the whole party can't travel together, and generally helps gameplay to proceed smoothly. Nonetheless, its specific form can't be overlooked.

The End of Time shows no signs of disorder or destruction, though a single platform in the void seems to be all that is left of the world. The brickwork, fence and single lamppost at the End of Time convey a serene and civilized -- if somewhat incongruous -- image of history's end. Furthermore, the End of Time is presented as a static location, not as an event. That time's end is taken for granted and used as a home base of sorts in Chrono Trigger is meaningful; note that it implicitly dismisses any number of end-of-the-world mythologies while simultaneously satirizing its own materialist position through the placement of an old-fashioned lamppost as the only light left in the universe. Because we are supposed to believe in so many different time periods and genres throughout the game, from a medieval war against demons to a robot-dominated future, the end of time cannot be one that reveals some transcendent meaning, because that would invalidate some of the era-specific struggles we are supposed to care about. For this reason, we get a minimalist End of Time that refuses to pass judgment on the past, to redeem it, or even to contextualize it. Unlike traditional afterlives in which justice is rewarded and evil is punished, the End of Time is simply an empty stadium after the big game. The struggles of humanity are over, and we find that their meaning must be in living them, not in any omnipotent and morally-charged retrospection.

Time is not literally cyclical in Chrono Trigger, yet the End of Time reminds me of Sisyphus' moment of accomplishment in Camus, the moment when his punishment (the rock rolling downhill once again) earns him a brief respite from his absurd toil. Though Camus' radical meaninglessness has no place in Chrono Trigger, his sense of rebellious lust for life in the face of absurdity does. The End of Time marks the final boundary of humanity's domain, but this boundary affirms what lies within it; it refutes the idea that altering history is somehow hubris by highlighting the lack of a outside authority to whom Crono might justify his actions. Potentiality, which is dead in 2300, is most alive at the End of Time, where the book of history lies open, the magic that can rewrite it is discovered, and the void gives humans implicit authority to do as they will.

Spekkio

What is significant about Spekkio is what he is not: a deity in the Western sense. The self-described "God of War" does not intervene in the events of the plot, has no particular moral authority, and is not omnipotent. Notably, he cannot grant magic to Robo (nor, later, to Ayla) because neither one is descended from humanity's magic-using ancestors; Spekkio is not even the source of magic, then, but only has the power to awaken it. The casual introduction of a god as comic relief shows that the game's designers bring a distinctively Japanese non-theocentric worldview to the game. Yeah, there's a God of War. So what? He is just another strange character in a game that has more than its share. His existence no more defines the meaning of the game-world than does the existence of lizard men, wizards and golems. The profound "God is Dead" message of Nietzsche more properly applies to Lavos than to Spekkio. Spekkio represents, rather, an off-hand dismissal of Voltaire's claim that "if God did not exist it would be necessary to invent him." The game's position seems to be that our problems are of the sort no god can solve, and that even finding a god (as Crono does) does not resolve the issues at hand.

Next time: The Gaze of the Hero legend, the supremacy of will, and Ayla the Ubermensch

But first: Elves, Elves, Elves!