Politics of the Cheongsam

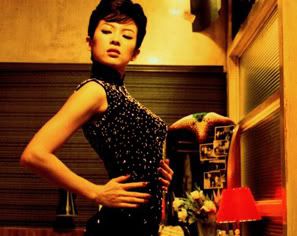

Screenshot from 2046 movie featuring Zhang Ziyi in a crystal adorned black velvet cheongsam

The cheongsam, also know as the qipao (in China and Taiwan), is a piece of Chinese garment that originated from the Manchus and modernised in Shanghai. Evolving from the classless, androgynous long robes traditionally worn by Chinese men, the cheongsam was regarded as the standard form of middle-class urban women’s dress in the 1930s in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore.

Clothing during the Manchu dynasty in the 19th and early 20th Century

Under the Manchu rule, dress codes were imposed on the Han population in China. Appearance and dress denoted their social status and origins. Both Manchu men and women typically wore gowns known as the qipao. It is a one-piece gown that fitted loosely and hung straight down the body.

Indigenous Han men wore full-length long gowns called the changshan) with trousers underneath it. Han women wore loosely cut two-piece aoqun (jacket and skirt) with trousers underneath the skirt, but wore the aoku (jacket and trousers) for their everyday dress. Clark (2000, p.2) noted in her historical study of the cheongsam, that “the gender distinction associated with trousers in China was the reverse of that in the West. Han women, not men, wore trousers in public, usually under a long upper garment.”

The birth of the modern body-hugging cheongsam

Most sources attribute the origins of the modern body-hugging cheongsam to Shanghai, know as the ‘Paris of the East’. Shanghai was a busy port with flourishing international connections and a large population of foreign entrepreneurs who won trading and residence rights through the Opium War in 1834 (Kaplan et al. 1979, p.43). Its trade connections and large population of foreigners made it increasingly subject to Western influence and the associated impact of modernity.

The body-hugging modern cheongsam was worn by society women, female movie stars, show girls and courtesans as a sign of sophistication and its images were widely circulated in Chinese movie production to express ‘Chineseness’, femininity and sexuality (Clark 2000, p.10). By the 1930s, the cheongsam was the regular outfit for middle-class and upper-class urban women in the cities of Shanghai, Beijing and overseas Chinese communities.

The cheongsam as a garment of power and discipline

It is interesting to note that the cheongsam was born alongside a growing awareness of women’s right and as a symbol of gender equality, but later became a garment that pushed women back to being in a subordinated (sexual) position to their male counterpart with the circulation of stereotypes in printed calendar posters and movie production in the 1930s and 1940s.

The Chinese female body, initially confined to the private (feminine) domain where it was covered by layers of clothing, was brought out to the public (masculine) domain and revealed its true form in a body-hugging cheongsam. Such a transition allowed the visibility of Chinese women in the public domain but also entangle them in an impersonal power relation, especially with the representation, exoticism and enforcement of stereotypes of the ‘modern’ Chinese women in a male-oriented Chinese society.

Foucault (1977, pp. 202-3) argued in his essay ‘Discipline and Punish’ that “he [‘she’, in this instance] who is subject to the field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; he makes them play spontaneously upon himself as he inscribes in himself the power relation in which he simultaneously plays both roles; he becomes the principle of his own subjection.”

Drawing on this argument, I would suggest that the cheongsam subject the individual to the powers of observation and puts the female wearer under a panoptical ‘male gaze’, constantly under his judgement. Brook (1999, p.112) noted that “theories of the disciplining functions of the ‘male gaze’ suggest that she enters public [masculine] space as a potentially disruptive, transgressive body and it is her position as spectacle [making a spectacle of herself] under the view of the masculine eye, that disciplines her back into line, returns her into a docile body.”

I would argued that the cheongsam is a disciplinary garment to regulate a woman’s body in public space. According to Foucault, discipline is a technique of power which provides procedures for training or for coercing bodies. Women in the body-hugging cheongsam will often feel extremely self-conscious of their bodies - for example, a slight weight increase will show in the garment. In this sense, women in cheongsam have to discipline their physical bodies to remain in shape and they have to constantly watch themselves in the public domain. The cheongsam forces women to discipline their bodies but also has a spectacle purpose by allows them to flaunt their disciplined bodies in the public domain.

Female emancipation or subordination?

In a male-orientated Chinese society, men exerted much of their own influence on the aesthetic and moral standards of women, but it cannot be denied that women went along with men’s ideas too.

Szeto (1997, p.63-64) noted that “the custom of foot binding which had prevailed since the Song dynasty [960-1279] was supported by the majority of men, who wanted their women vulnerable, submissive and ultimately under their control” and argued that the selection of the cheongsam as Chinese women’s national dress was “significant” after “being released from such restrictive traditions”

I would suggest that the modern cheongsam in the early 20th century is analogous to the torturous ancient custom of foot-binding, where women are being restricted and bounded within the body-hugging shell of the garment and subordinated to the control and judgement of the panoptical public gaze.

The cheongsam is a garment that reflected tradition, modernity, fashion and cultural change in the early 20th century. It is a garment that was born alongside a growing awareness of women’s rights and offered women new-found freedom in expressing herself and her sexuality. However it is also a garment that reinforce Western feminine stereotypes and thus to objectifies the wearers. As much as it liberates the wearer, the cheongsam is also a disciplinary garment that restricts the female body and controls it under the panoptical male gaze.

References

- Clark, Hazel (2000) The Cheongsam. New York: Oxford University Press

- Brook, Barbara (1999) Feminist Perspectives on the Body. New York: Pearson Education Limited

- Foucault, Michel (1977) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans: Allen Lane. London: Penguin Press

- Kaplan, Fredric M. (1979) Encyclopaedia of China Today. London: Macmillan Press Ltd

- Szeto, Naomi Y. (1997) Cheungsam: Fashion, Culture and Gender. In: Robert, Claire (ed) (1997) Chinese Dress 1700-1900s: Evolution and Revolution. Australia: Powerhouse Publishing. p.54-64