STC Endgame: A Night With The Actors Transcript & New Photos; Performance Photos & Reviews

Once again, our Sydney Correspondent Yvette has some through, providing notes for this complete transcript of the 13 April Night With The Actors event. Actors Hugo Weaving, Bruce Spence, Tom Budge and Sarah Peirse sat for a Q & A session following that evening's performance of Sydney Theatre Company's production of Endgame. Yvette and some other lucky audience members in attendance took some great photos of the event, which I'll also embed. While I've done my best to ensure accuracy, please bear in mind that this is my transcript of another person's notes, so transcribing errors along the way are always possible. If you were at this event and have any corrections to offer, do let us know. As always, my undying thanks to Yvette for her kindness in letting those of us not able to make it to Sydney (or to that specific performance) experience it vicariously.

Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton Photo: Yvette/@LyridsMC via Instagram

[Note: Andrew Upton's introduction and initial remarks weren't copied and are thus abbreviated, as are some audience questions. Other remarks are edited for clarity and because, in some instances, they weren't heard properly. Again, apologies. ;) ]

Andrew Upton: We tried to be true to the text... Inside the play, there's supposed to be a really precise sense of space and time. So that was the process we used on Waiting for Godot. And then in talking to Hugo [about the current season], we decided we'd like to revisit the "Beckett Experience" . And it really is quite a distinct experience. The language is so strong, the imagery so rich, and the emotional side is so deep and rewarding. I know it appears quite bleak from the outside or as you glance off it as a reader or as an audience, but [from a creative standpoint] it's incredibly generous. Incredibly generous language, and constructions and scenarios. So when you're talking about having what we've tried to say in it, which is, just follow the directions. They are illuminating and liberating. They're very, very scripted on the surface, and yet once you get inside them, there's 150 emotions being unpent. And with that liberation...Once you face all of it, there's a lot of philosophy, a lot of cross-referencing, there's a lot of deep-- [whistle from the audience] There's a cricket! [laughter]... there's a lot of detail... that I could not link link any poem to to myself. So we... and just followed the instructions.

Moderator: I imagine that being too literal with Beckett would suck he magic out of it.

AU: Yes...

Moderator: I wonder how much you need to know to create the play, and how much depth, obviously... deciding that Hamm had polio at 13 [for example] and that's why his legs don't work might not fit [Beckett's directives], but how much real-world stuff did you need to hold on to, and how much could you do without ...?

AU: Well, that's a fascinating question, actually. Because that is the great misunderstanding-- other than there being no humor-- around Beckett, is that it's obtuse and unrealistic. And actually it's as it's as realistic and any Chekhov .. it's as naturalistic as any piece of Gorky or Ibsen. It's not crazy, jazzed up ... It's a really, really realistic piece. And this realism inside that needs to be honored quite rigorously by the actors and the director. They can't bend the directions. Because [narrative] "answers" like polio or schizophrenia or depression aren't really enjoyable, and aren't answers that allow you to resonate. So you avoid such prosaic [choices], but they play remains very real about our sense of the apocalypse. About the story of how much Hamm tells, how much that's true. How much truth lies inside. Is it the story of how Hamm has failed, how all of us fail.

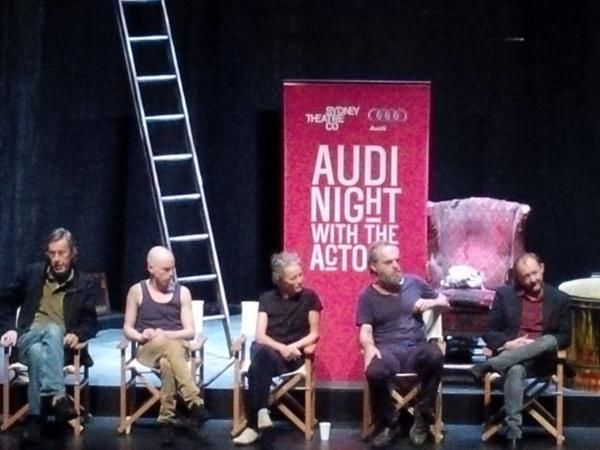

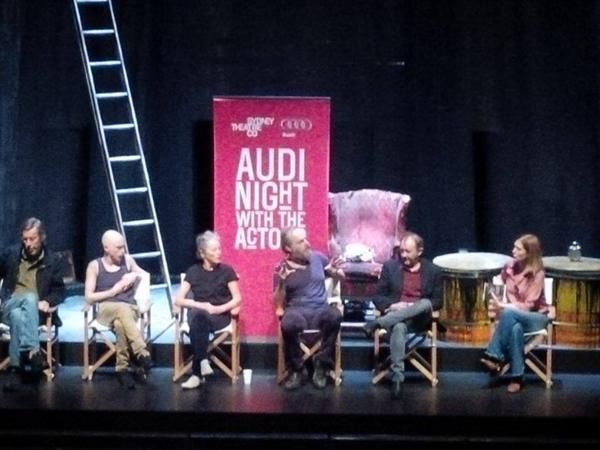

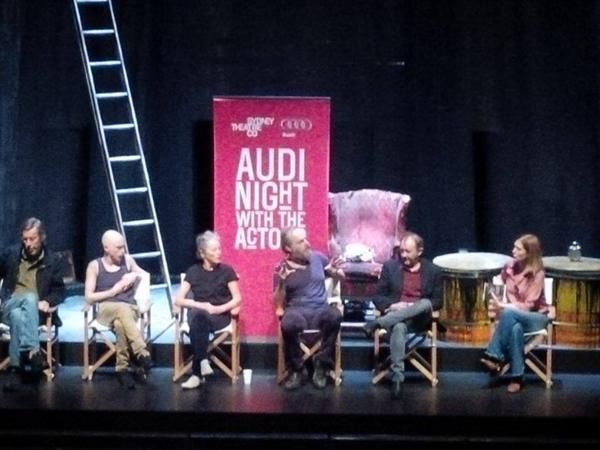

L to R: Bruce Spence, Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving, Andrew Upton and moderator Sarah Goodes. Photo: Amber Gokken via Twitter/Instagram

[Upton introduces the cast-- Hugo Weaving, Sarah Peirse, Tom Budge and Bruce Spence--who take their seats onstage]

Moderator: As actors, do you come from the outside in or do you work from the inside out, and how much truth do you need to pin down [your characters]?

Hugo Weaving: I tend to work from the outside in, I think, because the truth is not apparent immediately. I take [character cues] from the text's architecture in, from observing [the play's] form and structure, and then try and maintain that form, and then slowly illuminate for ourselves something about the internal journey to doom of these of these characters.

Moderator: Sarah, did you find, in the bin--

Sarah Peirse: It was HOT in the bin [laughs]. Yeah, he's right... the architecture of the writing informs the way in which you start to understand rhythms that are within it. And you're definitely surfing some fairly usual territory... [At the beginning of rehearsals] I was reasonably unsure about how it would proceed, but then, actually, if you just keep reading, and keep participating in the process of doing the lines out loud, and listening, in fact, the journey sort of makes itself apparent. That was an interesting experience.

Hugo Weaving: For any of you that play music.. I'm not a musician, but I would think it would be quite similar to being in an orchestra, or being in a small group, and working through a piece of music for the first time. You read music and you observe the score and meter, and the intervals and pauses-- you observe the structure of it, and then, after while, the more you play that, the more you hear that, the more... the reasons you find for it being in the first place start to become apparent to you, and I think that's very true of Beckett.

Moderator: What process did you need to find in the rehearsal room to bring the humor alive, or was the humor something that just bubbled up of its own accord?

Andrew Upton: It's pretty impressive... it's got some of the funniest lines hidden in it, but I do fear that if you read the outside world that is depicted too heavily, [the humor] is easy to lose sight of... "Oh god, it's the end of the world, I'm a goner and there are all of these poor people in bins" [Laughter] But if you're just IN there, a line like 'What's to keep me from going' ... [??]

Hugo Weaving: Even though it's the end of the world, and [the population is] down to four people...and they certainly think about it [being] very hard...Even if you were in that place, you would have to assume... they still have to resist... they can't think about it 24/7, otherwise they'd just go mad. Well, they probably ARE mad [laughter]. They have to pass the time, and disappear into flights of fantasy, I suppose, in order to relieve the terrible boredom and despair. Therefore, it's humorous. It becomes funny, despite... well, it's both. It's a deeply serious play, but it is funny. And I think, [in the worst of it], the relationships seem to be they key to finding humor. The pairings, and the way those two groups interact with each other. And I think a lot of the initial humor seems to come from that.

Moderator: Tom, what was your experience in the rehearsal room?

Tom Budge: Um... difficult. [Laughs] At first. I found the language-- to read-- it's real exciting and lovely. But I found it really hard to push it into a flow. And it took quite a lot out of me to get the highs and lows of what we had to do. I'm still figuring things out [Laughs]. It's really interesting-- you do have a moment, sometimes, I'm back in my little cave back there, I'm thinking about what we've just done, or something, and I'm thinking that's the truest version of that interaction or something, and then I'll turn that around in my brain [the next time we have to do the play] and think, 'Oh, no! That wasn't it!' It's still evolving, for me, still changing in small ways.

Andrew Upton: It's very, very alive drama.

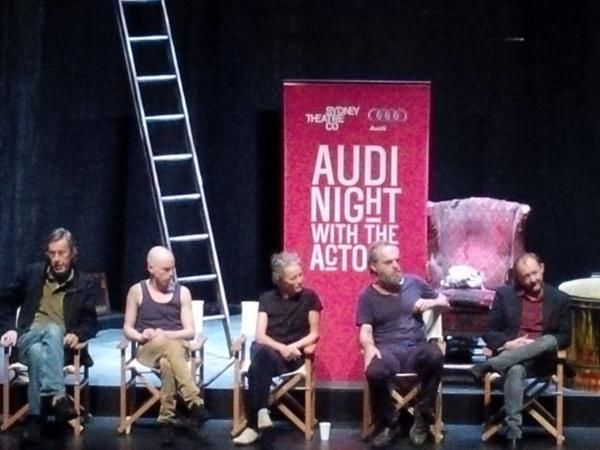

Night with The Actors photo: Sienna W via Twitter

Moderator: And Bruce?

Bruce Spence: It's my first play in a bin [Laughs] Look, I've found it a superb journey. Mainly, to be really honest, It was... the text... it's always in the text. That's where Beckett is. And I'm sure that if you go and see another production of Endgame, it'll be totally different to this one and so on. They're all different, because it's the human contribution that's made. Particularly I think Andrew really has coached lots of textual and dramatic stuff out of us too, so I really give him a lot of credit for that. I've found it a wonderful journey. The comedy, or should I say the humor, just comes out of the moment, out of the language. You don't consciously look for it. Although Beckett did love vaudevillians, he loved sort of raw comedy, et cetera, you can see that in his sort of logic. But also, I just wanted to make a point: I think Beckett, Endgame, Godot, et cetera,is part of a long legacy of writers like this. Especially from when the absurdists started writing, people like Beckett, Joyce and Pirandello and a million others. Then you had the logic of The Goon Show. And if you remember The Goon Show, there's this sort of distorted logic in that that's very similar to this, and then on and on, and even to Monty Python, etc, and I think a lot of people, a lot of writers even now owe a lot to Beckett, and that sort of way that he saw the world. That sort of jagged, distorted way.

Moderator: One final question for Hugo and Andrew, before we take questions from the audience: What was the evolution of working together, going from Waiting For Godot [in 2013] to Endgame? Did you develop a shorthand, or did you have to free-fall into it as a whole sort of experience?

Hugo Weaving: Let me answer: working on Godot was very, very difficult. Really the hardest thing that I had ever done, and I think that's true for Richard [Roxburgh] as well. And it was pretty difficult for Andrew. So it was a very, very difficult play, but an incredibly rewarding play, and it was the most extraordinary experience. I really loved working on that, I loved working with Andrew on it, I think Andrew sensed that it was-- I really think Andrew kind of gets Beckett in a great way. So once we picked into that seam, we were talking about perhaps doing another Beckett, and then Andrew suggested we do Endgame. So it really been a logical progression for us.

Andrew Upton: Yeah, I think we took the harder [play first]... it's hard to describe. It is so plain and simple, Beckett's work, and that's really hard to get. It's hard to play, as actors, it's hard to get it right, hard to get at the dialogue when you're doing so much action, it's very, very difficult to hold in your hand, very mercurial. And I think all of those terrifying lessons-- those rehearsals, battered as we were, we couldn't...

Hugo Weaving: It was an emotional release, our first weeks.

Andrew Upton: Beckett is demanding. I think audiences know that, and they weren't expecting tea. It was a very free flowing experience.

Hugo Weaving: The first thing I think I learned doing Godot, that I brought into this [Endgame], was the technical demands of the piece are so acute. And yet also-- you have to observe the structure-- but you need to to be entirely present. And open every second of the play. And I think that's probably true with every play, but with Beckett, somehow, much more extremely true than any other playwright. And I think it as a wonderful thing to discover, to bring to this [play.]

Moderator: It sounds like a real leap of faith.

Andrew Upton: Yeah, it's a leap of faith, all right [laughter].

"Watched "Lord Elrond"- Hugo Weaving's play #Endgame . Marvellous performance! Panel was impressive too." Sienna W via Twitter

Moderator: It sounds like a real emotional tumble. You were talking about music earlier [Hugo]... that at some point you have to let go.

Hugo Weaving: Well, Tamas Ascher, not Andy, was going to direct Waiting for Godot, and he couldn't come for the first week. He was indisposed, so Andrew took over rehearsals for the first week, and we weren't missing him anyway, because Tamas is Hungarian, so everything has to go through a translator, so we thought maybe we'll make the most of this because we'll have a talk alone about Beckett because [Tamas] couldn't immediately come [to Sydney]. And then he didn't come... and it became very clear during the second week of rehearsals that he WASN'T coming. [Laughs].

Andrew Upton: Not at all.

Tom Budge: How appropriate! [Laughs] Because it's CALLED...

Hugo Weaving: And so Andrew took over... and it was a challenge going forward, [though] it's not hard for me have faith in Andrew, that's very easy. That was a very good side effect. But it was suddenly a very different experience and a great experience, doing this play. A very exciting [rehearsal] room. A very open room.

"Happy birthday Samuel Beckett! What an evening at SydneyTheatreCo #Endgame #HugoWeaving #TomBudge #AndrewUpton" Valerie L via Twitter

Question #1 from the audience: Could you describe the role of silence in the play? The silences and pauses seem so 'active'. Was that a conscious choice?

Hugo Weaving: Well, there are pauses that Beckett had, and a Beckett pause probably lasts between three and five 'beats', I suppose, then there are long pauses, and then there are silences that we have. So there are a couple of moments where we observe a sort of full stupid, or dumb silence where nothing is happening at all, almost, I suppose, it's anti-theatrical in a way, but it's a quite interesting place to play... There's a lot going on inside [these characters], but it's when the death...the nature of where they are fills them, that nothing can be said and nothing can happen, so actually, in a way, that can provide desperate, empty silences from the point of view of the characters. But they're full of a lot of internal [reflection].

Bruce Spence: It's like records of music, really. It's the language, it's the dramatic action that's happened before, the silence, and the dramatic action that might follow the silence. But there are silences and SILENCES. We had... when we were doing rehearsal at one stage, we paused at every pause, and it went on and on and on, and then we realized, 'hang on, that silence is that long, and THAT silence is THAT long, and that silence is THAT long.' [Laughs] That pause is that long. You need to sort of play that out. In all drama, whether it's Beckett or whoever. It's an organic thing. The factor that really determines a lot of that are the individuals that you're working opposite. And so, with the four of us, we sort of combine and create an energy, and that's what creates that music.

Sarah Peirse: But also, essentially, it's the transaction that the performers have with the audience that actually forms the silence... the performers introduce the silence, and the audience is where the silence is met.

Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton. Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

Question #2: Do you think the dramatic impact of the play has changed in the decades since the play was originally written? Beckett once said, "There are a heap of words, but no drama." Is this still true?

Andrew Upton: I think there's a great deal of drama in Endgame, actually. It's got a gruesome drive inside it that's quite relentless. Made-- only made riveting by this feeling I've sort of whipped into them. [Laughs]

Hugo Weaving: He described it... He said 'Godot is this long play about these awful people' [Laughs].... He said, 'God help me, I can do no other'. [Laughs]

Andrew Upton: [Paraphrased] There is no highly-composed, staged 'drama' in the classical sense, but inherent drama created by the interaction of the characters.

Hugo Weaving: And even in the telling of the story, like Hamm's preposterously long story, is sort of told in four or five voices, so there's drama inside that, there's the storyteller himself, he's kind of acting the storyteller role, and then he's telling the story from a couple of individuals' points of view, and then there's... you've also got a cricket getting comedy gone... that's dark... there is quite a lot of human turmoil in that drama, if you can only find one. Beckett was probably saying to all the rest of us not to expect, you know, damsels getting run over by a train [or other stock plot devices.] There's an enormous amount of human turmoil and drama in ALL of Beckett's work, fantastic self-censorship, fantastic celebration of failure, and not knowing, and not being able to carry on. But carrying on anyway.

Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton. Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

Question #3: It struck me that Hugo didn't move his feet for the duration of the performance. There was no fidgeting. How did Hugo and Tom go about developing the different physical aspects of their characters? Was it intuitive, text-based, individual or mutual approach?

Tom Budge: Beckett states specific things about Clov [in his stage directions, such as his] stiff, staggering walk. And so for the first week [of rehearsals] I had one fused leg, and moved the other one, so I kind of walked around like that. On the Friday night of the first week, I was back in my hotel room. I was limping. [Laughs] I couldn't bend my leg. So I thought, aw, that's probably going to ruin everything. [Laughs] So I kind of read a lot into his-- Clov's final speech, where he says now that he's so bowed, and I loved the idea that the world is just crushing him. So that when he does fall, he will be fully pushed to the ground. So I liked the idea of a bent back pushing him down. And that is also symmetrical, so I'm mindful of the physio of it. [Laughs]. That's the idea of of it. So that's why I kind of ended up on that foot.

Hugo Weaving: Again, Beckett [specifies that] Hamm can't walk and is blind. So I decided... he's sitting in a chair, and can't lie down and can't, you know [stand]... that his feet were probably swollen. So we got these very thick knitted socks. My feet do go to sleep. But they're not... I do occasinally find it difficult in the curtain call to walk. [Laughs] But the hardest thing for me was the... not being able to see. And in rehearsal trying to work out whether it was best for me to literally not be able to see, or to be able to see a little bit through the glasses. And.. [the lenses are] painted, so it's like looking at the back of a white wall very close to my eyes. But with little flecks I can see through, which I thought was important, because I couldn't-- It's fiunny. I found it very hard to reference.. I found it very hard to speak. I couldn't reference the visual. I found it very hard to judge logically in [telling] that long story. I found it very hard without any visual references to do. So that was a big challenge for me.

Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twittter

Question #4: Just coming off that physicality question, my question is for Bruce Spence: You're a prolific voiceover artist as well as a film and stage actor with a distinctive voice. What are the differences between voice acting and fully embodied roles? How do you approach creating a character with no physical presence?

Bruce Spence: Well, it was hard doing the bin. [Laughs] Obviously I had to thnk about that. Especially in rehearsal it was real hard. This one's much easier. It's the trext that really helps me. It must sound boring to say that, but I don't really, consciously think up a voice. I just look at the script, and also listen to the music of the other actors too. I just work off the text. And it's it's just [how] the character that sort enters the situation at the turn of the vocal cues. When you're doing animation [or voice roles where no other actors are present], you're often given a character breakdown. So the character breakdown will often help you find the voice anyway. Once you know the character's journey, et cetera, that will help you find the character's sort of vocal psyche, level et cetera.

Hugo Weaving: The other thing is, in animation, the animators these days actually film actors during the recording, because they want to see the actor's face. They use the actor's face to animate the character. So whatever you're doing, they absolutely... now, they get try and the actors together to record, or they have you go back and re-record [lines in post-production as changes are made.] But the animators increasingly really want to see the actor's face. And they get all the actors to do physical stuff, whether you're doing... whatever you're being, whatever creature it is that you're animating. The animators love that.

Bruce Spence: They'll also provide you the drawings too, of your character, to kind of help you with your characterization.

Photo: Sydney Theatre Co via Twitter/Instagram

Question #5: What was Sarah's experience of being the only woman in an ostensibly very 'masculine' play?

Sarah Peirse: I didn't feel particularly... I guess in some respects Nell is not... everybody's representative of beyond themselves, of beyond their particular character. I didn't feel particularly that the lack... other than the lack of potential of exploring Nell anyway. But she's also... she's the first one to die of these four, so I think that the read became, rather than a gender exploration, it became a journey of her limited returns. So really it was an experience of that rather than anything I think I felt particularly [about her gender.] Other than being conscious that this [relationship between Nagg and Nell] is a long marriage, so there were the rhythms of the marriage that it placed. The sort of irritations and the affection and the companionship and the longevity. And then at times the sort of.. we're ourselves by Hamm being my son, so all of a sudden you're playing or existing between two males, and I felt that that was a... for an older, dying woman whose husband and son were present, they were elements that I was conscious of. But that was not.. I wasn't particularly thinking in gender terms.

Hugo Weaving: It's interesting that you say that too, because I often think of these characters as being of indeterminate gender, unaware, and I think that Hamm overreacts at his mother, being the character of Hamm. So I sense very strongly his relationship to his mother, and also to his father, in his downfall...

Photo: Valerie L via Twitter

Question #6: Can you comment on the set design?

Hugo Weaving: Nick [Schlieper]'s not here... Nick did design the set and the lighting. I know initially he was looking at a lot of pictures of big water towers, and he was thinking of the play as a vertical play rather than a horizontal one. His set for Godot was a fantastic, open landscape-- for the proscenium, but with a great sense of space. And he was kind of interested in the claustrophobia, the nature of a set like this. Also, I think there was a [person] that used to take refuge in a tower up in the hills just outside Lebanon, just the walls, and I suppose he had that in the back of his mind as well.

Andrew Upton: We had a lot of chats about setting up a peopled space [creatively approaching Beckett's stark set specifications]

Hugo Weaving: Basically he just says 'Two windows. A door. A chair. Two bins. Grey light'. That's really not much. So as long as you have those, don't add too much onto it. Just don't. You can't stick anything on Beckett, it won't stay. It won't work.

Moderator: That's all we have time for. Thanks to our cast

"Rakish, intelligent and modest as always." Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

***

Here are excerpts from the latest review of STC Endgame, with a few new production photos (by Lisa Tomasetti) originally posted to STC Facebook. STC recently posted a gallery of 13 of Tomasetti's performance stills, though not the full range of photos that have appeared in reviews and elsewhere.. so there remains hope we still haven't seen them all. As always, the full reviews at sites of origin are well worth a look, so just follow the links.

Tom Budge as Clov and Hugo Weaving as Hamm Photo (all 3 performance photos): Lisa Tomasetti

David Kary, Sydney Arts Guide: "A Samuel Beckett night at the theatre is like no other. One is just taken over by his bold, raw take on life. Even after all these years, one is still gobsmacked, stunned, by what one is taking place on stage. The experience is like being set upon by the coldest, bleakest wind....

One of our finest actors, Hugo Weaving, delivers one of his most memorable performances as one of Beckett’s most cruel, cantankerous characters, the blind tyrant, Hamm... The performances by Tom Budge as Clov, just brilliant, and Sarah Peirse and Bruce Spence, as his incarcerated parents are perfectly judged...

Summing up, this is the kind of play that gives one the creeps. I saw ENDGAME over a week a go, and I am still haunted by it. Hamm’s deeply sadistic nature…Clov endlessly running after him…hunchbacked…climbing up and down ladders…reporting back to him that he has seen nothing....All I can say is…be prepared!"

Maire Sheehan, AltMedia: "Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame makes what might seem tedious mesmerising as the players’ every gesture, word, and expression evoke a range of responses from the tragic to the ludicrous...

Hugo Weaving is mesmerising. He is strapped into a chair and wears glasses that block out his sight. He is the one in control, or is he? He issues orders but he cannot move. The sparse stage setting and directions make Weaving’s smallest gesture highly visible and open to interpretation...

With a limited set and brilliant performances, STC’s production of Samuel Beckett’s absurdist masterpiece is not to be missed. "

Syke On Stage (Facebook): "After Godot, I suppose, Endgame, a one-act play with just four characters, probably stands as SB’s tour de force and director, Andrew Upton, has milked it for everything it’s worth, with his actors displaying the very keenest sense of comic timing...

While the performances that surround Weaving’s are robust, it’s Hugo’s production: suddenly and singularly, his idiosyncrasies and particularities-his Hugoisms-are optimally exploited; his deliberation in diction, declamatory disposition and facial contortions are all exceptionally well-utilised here, making for (at the obvious risk of alliteration) a charismatic, colourful and completely compelling characterisation...

Upton and team have encapsulated Endgame as precisely and evocatively as I can envisage being achieved. This, for mine, is definitive Beckett, the kind of Beckett which Beckett would’ve heartily endorsed. The man whose parents had high hopes of entering their quantity surveying enterprise didn’t disappoint, having become a surveyor of the human condition: marking it up, measuring, calibrating and calculating, so that we might build a chillingly accurate picture of ourselves; our foibles and follies. Upton has dusted it off and made it vibrant, even in its dinginess, all over again."

"Having a chat with #HugoWeaving post #Endgame #play at #STC #theatre . Great #Actor..." Amber Gokken via Twitter/Instagram

Diana Simonds, Stage Noise: "In 2013, the cast of STC's Waiting For Godot waited in vain for fabled Hungarian director Tamas Ascher to arrive and take charge of rehearsals. He was unwell and, at the last minute withdrew, giving STC's artistic director Andrew Upton approximately ten minutes' notice to take over. The result was a triumph for him and actors Hugo Weaving, Richard Roxburgh, Luke Mullins and Philip Quast... There were some churlish types however who whispered that Upton was somehow merely the beneficiary of Ascher's phoned in instructions via associate Anna Lengyel: that the production surely wasn't really his work…was it? The doubters should now be eating a large serving of humble pie if they were at the first night of Upton's latest adventures in BeckettWorld...

Fascinating then that the production reunites Upton and Weaving: two men whose great friendship has recently been celebrated in print in the weekend papers. They seem, on the face of it, to embody opposing qualities: Weaving - all grounded gravitas and Upton - all impish flightiness. Yet appearances are deceiving and, of course, the superficial is exactly that. From their close collaboration on Endgame it might be said that each brings out the opposite in the other, so Weaving's old man Hamm is as capricious as Ariel even though he is confined to a chair and by his blindness. And Upton's overall vision of Samuel Beckett's one hour-50 minutes of waiting for the end of the world is at once as terrifying and hilarious as that unthinkable but logically likely event might really be... They are aided and abetted in the enterprise by a superb team whose expertise is exhilarating in its creativity and attention to detail...

Budge and Weaving bicker relentlessly but the weight of their miserable discontent is leavened by the ability of both actors to feel and extract every drop of humour from a word, a pause, a look, an intonation. The continuing ripples of laughter and outbreaks of chuckles and chortles coming from an audience in attendance at almost two hours of the end of the world is a tribute to the actors and their director in realising the play's craftily concealed possibilities...

Like the moment in chess when it becomes clear all is lost, Endgame is not easy, but like chess, if surrender is inevitable that's when something else happens. In Beckett's play that something is a play that rewards the capitulation of both audience and actors alike: give yourself up to it and the prize is intoxicating and life-enhancing. The end of the world may possibly be quite similar... Endgame will sell out and no extension is possible as Upton and Weaving will be leaving for the Barbican Theatre for the restaging there of STC's Waiting For Godot. Miraculously the original cast has been reassembled (Luke Mullins is currently playing Clov in the Melbourne Theatre Company's own Endgame!) and I hope to be reporting on it from London. Meanwhile: this Endgame is a brilliant production and not to be missed."

A behind-the-scenes look at Endgame's trailer, via STC Instagram

Cassie Tongue, Aussie Theatre: "Last year, Weaving and director Kip Williams turned the Roslyn Packer Theatre (formerly the Sydney Theatre) inside out, and Weaving’s Macbeth filled the gaping auditorium, filling the extraordinarily large space with his tormented Scottish King. This year, as Beckett’s Hamm, Weaving is confined to a chair onstage, and still he fills the room and draws the eye consistently, and he does it with a marriage of harshness, weariness, and a pinprick or two of vulnerability that melts into the darkness, leaving with a mess that lingers. It’s thrilling...

It’s an astonishing performance because of its exhaustive complexity; Weaving’s own brilliance allows him to create a Hamm that radiates authenticity; not quite a broad-strokes tyrant or distant cipher, but someone who dances on the edge of sympathetic before pulling back and ordering instead a cruel command...

Upton and Weaving work well together; in Upton’s Waiting for Godot, which will tour London’s Barbican Theatre later this year, Weaving’s Vladimir was disarmingly good. Here, in Endgame, which Weaving has associate directed, together they creates the tiniest sensations that tend to take a corner of the brain and refuse to be forgotten...

Upton’s directorial touch is never light, it’s too decisive to be light, but between Weaving’s mastery from his chair and Budge’s bent-double pottering, occasionally with one battered bunny slipper and one boot on, and the cracked-white faces of Nell and Nagg peeping and huddling, and the softest sounds of dripping water, it becomes easy to think he’s not there at all, that this play has stood in its place at the Roslyn Packer for a hundred years, that these four have lived here too long, long before and after Upton showed his hand and shaped this one hundred or so minutes’ worth, and that’s perhaps the greatest compliment it can be given."

***

You can hear Bruce Spence's ABC Radio interview about Endgame and his film career here.

In Other Hugo Weaving News

The Key Man is now available to stream on Netflix in the US.

The Dressmaker is set to complete post-production by the end of June. an early cut is being shown to potential buyers at the Cannes Film Festival this month; according to Inside Film, the distribution right for 18 countries have already been snapped up, and the film will be screened for potential US buyers on 30 April. The film opens in Australia on 22 October and might possibly have its international premiere in September at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Healing has been awarded the ADG Finders Award by the Australian Directors Guild, according to Inside Film. The award is given to the most accomplished submitted film which has yet to receive US distribution. Director Craig Monahan "will accompany the film when it’s screened later in the year for distributors, managers and agents in LA and NY." Ideally this will help the film get deserved theatrical distribution, and might spur Anchor Bay into rehinking its appalling treatment of the DVD release and its laughably inaccurate cover art, which I respect the cast and filmmakers too much to display here. Suffice to say that apart from a poorly color-enhanced image featuring Don Hany and the eagle (a more artistic version of which served as the film's Australian poster art and home release art) NOTHING depicted on Anchor Bay's imaginary cover actually appears in the film. I thought this sort of insulting treatment of foreign films in US home release died out in the VHS era, but alas, no. Let's hope it's not too late to change Anchor Bay's mind. If they release the DVD with that cover, I certainly won't be wasting my money on it... I have already bought the Aussie version. Most of all I'd like to see Healing in the cinema setting it richly deserves.

Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton Photo: Yvette/@LyridsMC via Instagram

[Note: Andrew Upton's introduction and initial remarks weren't copied and are thus abbreviated, as are some audience questions. Other remarks are edited for clarity and because, in some instances, they weren't heard properly. Again, apologies. ;) ]

Andrew Upton: We tried to be true to the text... Inside the play, there's supposed to be a really precise sense of space and time. So that was the process we used on Waiting for Godot. And then in talking to Hugo [about the current season], we decided we'd like to revisit the "Beckett Experience" . And it really is quite a distinct experience. The language is so strong, the imagery so rich, and the emotional side is so deep and rewarding. I know it appears quite bleak from the outside or as you glance off it as a reader or as an audience, but [from a creative standpoint] it's incredibly generous. Incredibly generous language, and constructions and scenarios. So when you're talking about having what we've tried to say in it, which is, just follow the directions. They are illuminating and liberating. They're very, very scripted on the surface, and yet once you get inside them, there's 150 emotions being unpent. And with that liberation...Once you face all of it, there's a lot of philosophy, a lot of cross-referencing, there's a lot of deep-- [whistle from the audience] There's a cricket! [laughter]... there's a lot of detail... that I could not link link any poem to to myself. So we... and just followed the instructions.

Moderator: I imagine that being too literal with Beckett would suck he magic out of it.

AU: Yes...

Moderator: I wonder how much you need to know to create the play, and how much depth, obviously... deciding that Hamm had polio at 13 [for example] and that's why his legs don't work might not fit [Beckett's directives], but how much real-world stuff did you need to hold on to, and how much could you do without ...?

AU: Well, that's a fascinating question, actually. Because that is the great misunderstanding-- other than there being no humor-- around Beckett, is that it's obtuse and unrealistic. And actually it's as it's as realistic and any Chekhov .. it's as naturalistic as any piece of Gorky or Ibsen. It's not crazy, jazzed up ... It's a really, really realistic piece. And this realism inside that needs to be honored quite rigorously by the actors and the director. They can't bend the directions. Because [narrative] "answers" like polio or schizophrenia or depression aren't really enjoyable, and aren't answers that allow you to resonate. So you avoid such prosaic [choices], but they play remains very real about our sense of the apocalypse. About the story of how much Hamm tells, how much that's true. How much truth lies inside. Is it the story of how Hamm has failed, how all of us fail.

L to R: Bruce Spence, Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving, Andrew Upton and moderator Sarah Goodes. Photo: Amber Gokken via Twitter/Instagram

[Upton introduces the cast-- Hugo Weaving, Sarah Peirse, Tom Budge and Bruce Spence--who take their seats onstage]

Moderator: As actors, do you come from the outside in or do you work from the inside out, and how much truth do you need to pin down [your characters]?

Hugo Weaving: I tend to work from the outside in, I think, because the truth is not apparent immediately. I take [character cues] from the text's architecture in, from observing [the play's] form and structure, and then try and maintain that form, and then slowly illuminate for ourselves something about the internal journey to doom of these of these characters.

Moderator: Sarah, did you find, in the bin--

Sarah Peirse: It was HOT in the bin [laughs]. Yeah, he's right... the architecture of the writing informs the way in which you start to understand rhythms that are within it. And you're definitely surfing some fairly usual territory... [At the beginning of rehearsals] I was reasonably unsure about how it would proceed, but then, actually, if you just keep reading, and keep participating in the process of doing the lines out loud, and listening, in fact, the journey sort of makes itself apparent. That was an interesting experience.

Hugo Weaving: For any of you that play music.. I'm not a musician, but I would think it would be quite similar to being in an orchestra, or being in a small group, and working through a piece of music for the first time. You read music and you observe the score and meter, and the intervals and pauses-- you observe the structure of it, and then, after while, the more you play that, the more you hear that, the more... the reasons you find for it being in the first place start to become apparent to you, and I think that's very true of Beckett.

Moderator: What process did you need to find in the rehearsal room to bring the humor alive, or was the humor something that just bubbled up of its own accord?

Andrew Upton: It's pretty impressive... it's got some of the funniest lines hidden in it, but I do fear that if you read the outside world that is depicted too heavily, [the humor] is easy to lose sight of... "Oh god, it's the end of the world, I'm a goner and there are all of these poor people in bins" [Laughter] But if you're just IN there, a line like 'What's to keep me from going' ... [??]

Hugo Weaving: Even though it's the end of the world, and [the population is] down to four people...and they certainly think about it [being] very hard...Even if you were in that place, you would have to assume... they still have to resist... they can't think about it 24/7, otherwise they'd just go mad. Well, they probably ARE mad [laughter]. They have to pass the time, and disappear into flights of fantasy, I suppose, in order to relieve the terrible boredom and despair. Therefore, it's humorous. It becomes funny, despite... well, it's both. It's a deeply serious play, but it is funny. And I think, [in the worst of it], the relationships seem to be they key to finding humor. The pairings, and the way those two groups interact with each other. And I think a lot of the initial humor seems to come from that.

Moderator: Tom, what was your experience in the rehearsal room?

Tom Budge: Um... difficult. [Laughs] At first. I found the language-- to read-- it's real exciting and lovely. But I found it really hard to push it into a flow. And it took quite a lot out of me to get the highs and lows of what we had to do. I'm still figuring things out [Laughs]. It's really interesting-- you do have a moment, sometimes, I'm back in my little cave back there, I'm thinking about what we've just done, or something, and I'm thinking that's the truest version of that interaction or something, and then I'll turn that around in my brain [the next time we have to do the play] and think, 'Oh, no! That wasn't it!' It's still evolving, for me, still changing in small ways.

Andrew Upton: It's very, very alive drama.

Night with The Actors photo: Sienna W via Twitter

Moderator: And Bruce?

Bruce Spence: It's my first play in a bin [Laughs] Look, I've found it a superb journey. Mainly, to be really honest, It was... the text... it's always in the text. That's where Beckett is. And I'm sure that if you go and see another production of Endgame, it'll be totally different to this one and so on. They're all different, because it's the human contribution that's made. Particularly I think Andrew really has coached lots of textual and dramatic stuff out of us too, so I really give him a lot of credit for that. I've found it a wonderful journey. The comedy, or should I say the humor, just comes out of the moment, out of the language. You don't consciously look for it. Although Beckett did love vaudevillians, he loved sort of raw comedy, et cetera, you can see that in his sort of logic. But also, I just wanted to make a point: I think Beckett, Endgame, Godot, et cetera,is part of a long legacy of writers like this. Especially from when the absurdists started writing, people like Beckett, Joyce and Pirandello and a million others. Then you had the logic of The Goon Show. And if you remember The Goon Show, there's this sort of distorted logic in that that's very similar to this, and then on and on, and even to Monty Python, etc, and I think a lot of people, a lot of writers even now owe a lot to Beckett, and that sort of way that he saw the world. That sort of jagged, distorted way.

Moderator: One final question for Hugo and Andrew, before we take questions from the audience: What was the evolution of working together, going from Waiting For Godot [in 2013] to Endgame? Did you develop a shorthand, or did you have to free-fall into it as a whole sort of experience?

Hugo Weaving: Let me answer: working on Godot was very, very difficult. Really the hardest thing that I had ever done, and I think that's true for Richard [Roxburgh] as well. And it was pretty difficult for Andrew. So it was a very, very difficult play, but an incredibly rewarding play, and it was the most extraordinary experience. I really loved working on that, I loved working with Andrew on it, I think Andrew sensed that it was-- I really think Andrew kind of gets Beckett in a great way. So once we picked into that seam, we were talking about perhaps doing another Beckett, and then Andrew suggested we do Endgame. So it really been a logical progression for us.

Andrew Upton: Yeah, I think we took the harder [play first]... it's hard to describe. It is so plain and simple, Beckett's work, and that's really hard to get. It's hard to play, as actors, it's hard to get it right, hard to get at the dialogue when you're doing so much action, it's very, very difficult to hold in your hand, very mercurial. And I think all of those terrifying lessons-- those rehearsals, battered as we were, we couldn't...

Hugo Weaving: It was an emotional release, our first weeks.

Andrew Upton: Beckett is demanding. I think audiences know that, and they weren't expecting tea. It was a very free flowing experience.

Hugo Weaving: The first thing I think I learned doing Godot, that I brought into this [Endgame], was the technical demands of the piece are so acute. And yet also-- you have to observe the structure-- but you need to to be entirely present. And open every second of the play. And I think that's probably true with every play, but with Beckett, somehow, much more extremely true than any other playwright. And I think it as a wonderful thing to discover, to bring to this [play.]

Moderator: It sounds like a real leap of faith.

Andrew Upton: Yeah, it's a leap of faith, all right [laughter].

"Watched "Lord Elrond"- Hugo Weaving's play #Endgame . Marvellous performance! Panel was impressive too." Sienna W via Twitter

Moderator: It sounds like a real emotional tumble. You were talking about music earlier [Hugo]... that at some point you have to let go.

Hugo Weaving: Well, Tamas Ascher, not Andy, was going to direct Waiting for Godot, and he couldn't come for the first week. He was indisposed, so Andrew took over rehearsals for the first week, and we weren't missing him anyway, because Tamas is Hungarian, so everything has to go through a translator, so we thought maybe we'll make the most of this because we'll have a talk alone about Beckett because [Tamas] couldn't immediately come [to Sydney]. And then he didn't come... and it became very clear during the second week of rehearsals that he WASN'T coming. [Laughs].

Andrew Upton: Not at all.

Tom Budge: How appropriate! [Laughs] Because it's CALLED...

Hugo Weaving: And so Andrew took over... and it was a challenge going forward, [though] it's not hard for me have faith in Andrew, that's very easy. That was a very good side effect. But it was suddenly a very different experience and a great experience, doing this play. A very exciting [rehearsal] room. A very open room.

"Happy birthday Samuel Beckett! What an evening at SydneyTheatreCo #Endgame #HugoWeaving #TomBudge #AndrewUpton" Valerie L via Twitter

Question #1 from the audience: Could you describe the role of silence in the play? The silences and pauses seem so 'active'. Was that a conscious choice?

Hugo Weaving: Well, there are pauses that Beckett had, and a Beckett pause probably lasts between three and five 'beats', I suppose, then there are long pauses, and then there are silences that we have. So there are a couple of moments where we observe a sort of full stupid, or dumb silence where nothing is happening at all, almost, I suppose, it's anti-theatrical in a way, but it's a quite interesting place to play... There's a lot going on inside [these characters], but it's when the death...the nature of where they are fills them, that nothing can be said and nothing can happen, so actually, in a way, that can provide desperate, empty silences from the point of view of the characters. But they're full of a lot of internal [reflection].

Bruce Spence: It's like records of music, really. It's the language, it's the dramatic action that's happened before, the silence, and the dramatic action that might follow the silence. But there are silences and SILENCES. We had... when we were doing rehearsal at one stage, we paused at every pause, and it went on and on and on, and then we realized, 'hang on, that silence is that long, and THAT silence is THAT long, and that silence is THAT long.' [Laughs] That pause is that long. You need to sort of play that out. In all drama, whether it's Beckett or whoever. It's an organic thing. The factor that really determines a lot of that are the individuals that you're working opposite. And so, with the four of us, we sort of combine and create an energy, and that's what creates that music.

Sarah Peirse: But also, essentially, it's the transaction that the performers have with the audience that actually forms the silence... the performers introduce the silence, and the audience is where the silence is met.

Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton. Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

Question #2: Do you think the dramatic impact of the play has changed in the decades since the play was originally written? Beckett once said, "There are a heap of words, but no drama." Is this still true?

Andrew Upton: I think there's a great deal of drama in Endgame, actually. It's got a gruesome drive inside it that's quite relentless. Made-- only made riveting by this feeling I've sort of whipped into them. [Laughs]

Hugo Weaving: He described it... He said 'Godot is this long play about these awful people' [Laughs].... He said, 'God help me, I can do no other'. [Laughs]

Andrew Upton: [Paraphrased] There is no highly-composed, staged 'drama' in the classical sense, but inherent drama created by the interaction of the characters.

Hugo Weaving: And even in the telling of the story, like Hamm's preposterously long story, is sort of told in four or five voices, so there's drama inside that, there's the storyteller himself, he's kind of acting the storyteller role, and then he's telling the story from a couple of individuals' points of view, and then there's... you've also got a cricket getting comedy gone... that's dark... there is quite a lot of human turmoil in that drama, if you can only find one. Beckett was probably saying to all the rest of us not to expect, you know, damsels getting run over by a train [or other stock plot devices.] There's an enormous amount of human turmoil and drama in ALL of Beckett's work, fantastic self-censorship, fantastic celebration of failure, and not knowing, and not being able to carry on. But carrying on anyway.

Tom Budge, Sarah Peirse, Hugo Weaving and Andrew Upton. Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

Question #3: It struck me that Hugo didn't move his feet for the duration of the performance. There was no fidgeting. How did Hugo and Tom go about developing the different physical aspects of their characters? Was it intuitive, text-based, individual or mutual approach?

Tom Budge: Beckett states specific things about Clov [in his stage directions, such as his] stiff, staggering walk. And so for the first week [of rehearsals] I had one fused leg, and moved the other one, so I kind of walked around like that. On the Friday night of the first week, I was back in my hotel room. I was limping. [Laughs] I couldn't bend my leg. So I thought, aw, that's probably going to ruin everything. [Laughs] So I kind of read a lot into his-- Clov's final speech, where he says now that he's so bowed, and I loved the idea that the world is just crushing him. So that when he does fall, he will be fully pushed to the ground. So I liked the idea of a bent back pushing him down. And that is also symmetrical, so I'm mindful of the physio of it. [Laughs]. That's the idea of of it. So that's why I kind of ended up on that foot.

Hugo Weaving: Again, Beckett [specifies that] Hamm can't walk and is blind. So I decided... he's sitting in a chair, and can't lie down and can't, you know [stand]... that his feet were probably swollen. So we got these very thick knitted socks. My feet do go to sleep. But they're not... I do occasinally find it difficult in the curtain call to walk. [Laughs] But the hardest thing for me was the... not being able to see. And in rehearsal trying to work out whether it was best for me to literally not be able to see, or to be able to see a little bit through the glasses. And.. [the lenses are] painted, so it's like looking at the back of a white wall very close to my eyes. But with little flecks I can see through, which I thought was important, because I couldn't-- It's fiunny. I found it very hard to reference.. I found it very hard to speak. I couldn't reference the visual. I found it very hard to judge logically in [telling] that long story. I found it very hard without any visual references to do. So that was a big challenge for me.

Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twittter

Question #4: Just coming off that physicality question, my question is for Bruce Spence: You're a prolific voiceover artist as well as a film and stage actor with a distinctive voice. What are the differences between voice acting and fully embodied roles? How do you approach creating a character with no physical presence?

Bruce Spence: Well, it was hard doing the bin. [Laughs] Obviously I had to thnk about that. Especially in rehearsal it was real hard. This one's much easier. It's the trext that really helps me. It must sound boring to say that, but I don't really, consciously think up a voice. I just look at the script, and also listen to the music of the other actors too. I just work off the text. And it's it's just [how] the character that sort enters the situation at the turn of the vocal cues. When you're doing animation [or voice roles where no other actors are present], you're often given a character breakdown. So the character breakdown will often help you find the voice anyway. Once you know the character's journey, et cetera, that will help you find the character's sort of vocal psyche, level et cetera.

Hugo Weaving: The other thing is, in animation, the animators these days actually film actors during the recording, because they want to see the actor's face. They use the actor's face to animate the character. So whatever you're doing, they absolutely... now, they get try and the actors together to record, or they have you go back and re-record [lines in post-production as changes are made.] But the animators increasingly really want to see the actor's face. And they get all the actors to do physical stuff, whether you're doing... whatever you're being, whatever creature it is that you're animating. The animators love that.

Bruce Spence: They'll also provide you the drawings too, of your character, to kind of help you with your characterization.

Photo: Sydney Theatre Co via Twitter/Instagram

Question #5: What was Sarah's experience of being the only woman in an ostensibly very 'masculine' play?

Sarah Peirse: I didn't feel particularly... I guess in some respects Nell is not... everybody's representative of beyond themselves, of beyond their particular character. I didn't feel particularly that the lack... other than the lack of potential of exploring Nell anyway. But she's also... she's the first one to die of these four, so I think that the read became, rather than a gender exploration, it became a journey of her limited returns. So really it was an experience of that rather than anything I think I felt particularly [about her gender.] Other than being conscious that this [relationship between Nagg and Nell] is a long marriage, so there were the rhythms of the marriage that it placed. The sort of irritations and the affection and the companionship and the longevity. And then at times the sort of.. we're ourselves by Hamm being my son, so all of a sudden you're playing or existing between two males, and I felt that that was a... for an older, dying woman whose husband and son were present, they were elements that I was conscious of. But that was not.. I wasn't particularly thinking in gender terms.

Hugo Weaving: It's interesting that you say that too, because I often think of these characters as being of indeterminate gender, unaware, and I think that Hamm overreacts at his mother, being the character of Hamm. So I sense very strongly his relationship to his mother, and also to his father, in his downfall...

Photo: Valerie L via Twitter

Question #6: Can you comment on the set design?

Hugo Weaving: Nick [Schlieper]'s not here... Nick did design the set and the lighting. I know initially he was looking at a lot of pictures of big water towers, and he was thinking of the play as a vertical play rather than a horizontal one. His set for Godot was a fantastic, open landscape-- for the proscenium, but with a great sense of space. And he was kind of interested in the claustrophobia, the nature of a set like this. Also, I think there was a [person] that used to take refuge in a tower up in the hills just outside Lebanon, just the walls, and I suppose he had that in the back of his mind as well.

Andrew Upton: We had a lot of chats about setting up a peopled space [creatively approaching Beckett's stark set specifications]

Hugo Weaving: Basically he just says 'Two windows. A door. A chair. Two bins. Grey light'. That's really not much. So as long as you have those, don't add too much onto it. Just don't. You can't stick anything on Beckett, it won't stay. It won't work.

Moderator: That's all we have time for. Thanks to our cast

"Rakish, intelligent and modest as always." Photo: Yvette ( @LyridsMC) via Twitter

***

Here are excerpts from the latest review of STC Endgame, with a few new production photos (by Lisa Tomasetti) originally posted to STC Facebook. STC recently posted a gallery of 13 of Tomasetti's performance stills, though not the full range of photos that have appeared in reviews and elsewhere.. so there remains hope we still haven't seen them all. As always, the full reviews at sites of origin are well worth a look, so just follow the links.

Tom Budge as Clov and Hugo Weaving as Hamm Photo (all 3 performance photos): Lisa Tomasetti

David Kary, Sydney Arts Guide: "A Samuel Beckett night at the theatre is like no other. One is just taken over by his bold, raw take on life. Even after all these years, one is still gobsmacked, stunned, by what one is taking place on stage. The experience is like being set upon by the coldest, bleakest wind....

One of our finest actors, Hugo Weaving, delivers one of his most memorable performances as one of Beckett’s most cruel, cantankerous characters, the blind tyrant, Hamm... The performances by Tom Budge as Clov, just brilliant, and Sarah Peirse and Bruce Spence, as his incarcerated parents are perfectly judged...

Summing up, this is the kind of play that gives one the creeps. I saw ENDGAME over a week a go, and I am still haunted by it. Hamm’s deeply sadistic nature…Clov endlessly running after him…hunchbacked…climbing up and down ladders…reporting back to him that he has seen nothing....All I can say is…be prepared!"

Maire Sheehan, AltMedia: "Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame makes what might seem tedious mesmerising as the players’ every gesture, word, and expression evoke a range of responses from the tragic to the ludicrous...

Hugo Weaving is mesmerising. He is strapped into a chair and wears glasses that block out his sight. He is the one in control, or is he? He issues orders but he cannot move. The sparse stage setting and directions make Weaving’s smallest gesture highly visible and open to interpretation...

With a limited set and brilliant performances, STC’s production of Samuel Beckett’s absurdist masterpiece is not to be missed. "

Syke On Stage (Facebook): "After Godot, I suppose, Endgame, a one-act play with just four characters, probably stands as SB’s tour de force and director, Andrew Upton, has milked it for everything it’s worth, with his actors displaying the very keenest sense of comic timing...

While the performances that surround Weaving’s are robust, it’s Hugo’s production: suddenly and singularly, his idiosyncrasies and particularities-his Hugoisms-are optimally exploited; his deliberation in diction, declamatory disposition and facial contortions are all exceptionally well-utilised here, making for (at the obvious risk of alliteration) a charismatic, colourful and completely compelling characterisation...

Upton and team have encapsulated Endgame as precisely and evocatively as I can envisage being achieved. This, for mine, is definitive Beckett, the kind of Beckett which Beckett would’ve heartily endorsed. The man whose parents had high hopes of entering their quantity surveying enterprise didn’t disappoint, having become a surveyor of the human condition: marking it up, measuring, calibrating and calculating, so that we might build a chillingly accurate picture of ourselves; our foibles and follies. Upton has dusted it off and made it vibrant, even in its dinginess, all over again."

"Having a chat with #HugoWeaving post #Endgame #play at #STC #theatre . Great #Actor..." Amber Gokken via Twitter/Instagram

Diana Simonds, Stage Noise: "In 2013, the cast of STC's Waiting For Godot waited in vain for fabled Hungarian director Tamas Ascher to arrive and take charge of rehearsals. He was unwell and, at the last minute withdrew, giving STC's artistic director Andrew Upton approximately ten minutes' notice to take over. The result was a triumph for him and actors Hugo Weaving, Richard Roxburgh, Luke Mullins and Philip Quast... There were some churlish types however who whispered that Upton was somehow merely the beneficiary of Ascher's phoned in instructions via associate Anna Lengyel: that the production surely wasn't really his work…was it? The doubters should now be eating a large serving of humble pie if they were at the first night of Upton's latest adventures in BeckettWorld...

Fascinating then that the production reunites Upton and Weaving: two men whose great friendship has recently been celebrated in print in the weekend papers. They seem, on the face of it, to embody opposing qualities: Weaving - all grounded gravitas and Upton - all impish flightiness. Yet appearances are deceiving and, of course, the superficial is exactly that. From their close collaboration on Endgame it might be said that each brings out the opposite in the other, so Weaving's old man Hamm is as capricious as Ariel even though he is confined to a chair and by his blindness. And Upton's overall vision of Samuel Beckett's one hour-50 minutes of waiting for the end of the world is at once as terrifying and hilarious as that unthinkable but logically likely event might really be... They are aided and abetted in the enterprise by a superb team whose expertise is exhilarating in its creativity and attention to detail...

Budge and Weaving bicker relentlessly but the weight of their miserable discontent is leavened by the ability of both actors to feel and extract every drop of humour from a word, a pause, a look, an intonation. The continuing ripples of laughter and outbreaks of chuckles and chortles coming from an audience in attendance at almost two hours of the end of the world is a tribute to the actors and their director in realising the play's craftily concealed possibilities...

Like the moment in chess when it becomes clear all is lost, Endgame is not easy, but like chess, if surrender is inevitable that's when something else happens. In Beckett's play that something is a play that rewards the capitulation of both audience and actors alike: give yourself up to it and the prize is intoxicating and life-enhancing. The end of the world may possibly be quite similar... Endgame will sell out and no extension is possible as Upton and Weaving will be leaving for the Barbican Theatre for the restaging there of STC's Waiting For Godot. Miraculously the original cast has been reassembled (Luke Mullins is currently playing Clov in the Melbourne Theatre Company's own Endgame!) and I hope to be reporting on it from London. Meanwhile: this Endgame is a brilliant production and not to be missed."

A behind-the-scenes look at Endgame's trailer, via STC Instagram

Cassie Tongue, Aussie Theatre: "Last year, Weaving and director Kip Williams turned the Roslyn Packer Theatre (formerly the Sydney Theatre) inside out, and Weaving’s Macbeth filled the gaping auditorium, filling the extraordinarily large space with his tormented Scottish King. This year, as Beckett’s Hamm, Weaving is confined to a chair onstage, and still he fills the room and draws the eye consistently, and he does it with a marriage of harshness, weariness, and a pinprick or two of vulnerability that melts into the darkness, leaving with a mess that lingers. It’s thrilling...

It’s an astonishing performance because of its exhaustive complexity; Weaving’s own brilliance allows him to create a Hamm that radiates authenticity; not quite a broad-strokes tyrant or distant cipher, but someone who dances on the edge of sympathetic before pulling back and ordering instead a cruel command...

Upton and Weaving work well together; in Upton’s Waiting for Godot, which will tour London’s Barbican Theatre later this year, Weaving’s Vladimir was disarmingly good. Here, in Endgame, which Weaving has associate directed, together they creates the tiniest sensations that tend to take a corner of the brain and refuse to be forgotten...

Upton’s directorial touch is never light, it’s too decisive to be light, but between Weaving’s mastery from his chair and Budge’s bent-double pottering, occasionally with one battered bunny slipper and one boot on, and the cracked-white faces of Nell and Nagg peeping and huddling, and the softest sounds of dripping water, it becomes easy to think he’s not there at all, that this play has stood in its place at the Roslyn Packer for a hundred years, that these four have lived here too long, long before and after Upton showed his hand and shaped this one hundred or so minutes’ worth, and that’s perhaps the greatest compliment it can be given."

***

You can hear Bruce Spence's ABC Radio interview about Endgame and his film career here.

In Other Hugo Weaving News

The Key Man is now available to stream on Netflix in the US.

The Dressmaker is set to complete post-production by the end of June. an early cut is being shown to potential buyers at the Cannes Film Festival this month; according to Inside Film, the distribution right for 18 countries have already been snapped up, and the film will be screened for potential US buyers on 30 April. The film opens in Australia on 22 October and might possibly have its international premiere in September at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Healing has been awarded the ADG Finders Award by the Australian Directors Guild, according to Inside Film. The award is given to the most accomplished submitted film which has yet to receive US distribution. Director Craig Monahan "will accompany the film when it’s screened later in the year for distributors, managers and agents in LA and NY." Ideally this will help the film get deserved theatrical distribution, and might spur Anchor Bay into rehinking its appalling treatment of the DVD release and its laughably inaccurate cover art, which I respect the cast and filmmakers too much to display here. Suffice to say that apart from a poorly color-enhanced image featuring Don Hany and the eagle (a more artistic version of which served as the film's Australian poster art and home release art) NOTHING depicted on Anchor Bay's imaginary cover actually appears in the film. I thought this sort of insulting treatment of foreign films in US home release died out in the VHS era, but alas, no. Let's hope it's not too late to change Anchor Bay's mind. If they release the DVD with that cover, I certainly won't be wasting my money on it... I have already bought the Aussie version. Most of all I'd like to see Healing in the cinema setting it richly deserves.