Iver B. Neumann, “RUSSIA AS EUROPE’S OTHER”

Now even that footstep of lost liberty

Is gone; and now like slave-born Muscovite,

I call it praise to suffer tyranny.

-- Sir Philip Sydney 1591, "Astrophel and Stella", Sonnet II.

If the Slavs, who more and more are falling under Russian influence, come to dominate Europe,

farewell to all that I consider to be the freedom, verve, and essence of European civilization.

-- Saint Marc Girardin 1835, quoted in Hammen 1952 : 31.

Abstract

A human collective forge identities for itself partly by the way they represent other human collectives - their ’others’.

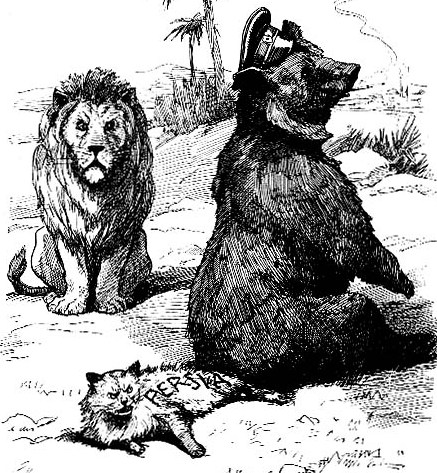

Russia stands out as an interesting case, where the much understudied question of European identity formation is concerned.

No matter which social practices a period has foregrounded:

- be they religious, bodily, intellectual, social, military, political, economic or otherwise,

- Russia has consistently been seen as an irregularity

Basing itself on 500 years of writings about:

- Muscovy, Russia and the Soviet Union

- in English, German, French and Danish,

- the paper demonstrates how Russia has quite consistently been represented as:

--- just having been tamed, civil, civilized,

--- just having begun to participate in European politics,

--- just having become part of Europe

Since the enlightenment, it has, furthermore, been:

- seen as a pupil and a learner, be that:

- a successful one (the authorised version of the enlightenment),

- a misguided one (the alternative version of the enlightenment),

- a fuks, who should learn, but refuses to do so (the authorised version of the 19th century),

- a truant (the 20th century),

- a gifted, but somewhat pigheaded one (the present)

- it is therefore deeply appropriate that, for the last 5 years,

--- the main metaphor used in European discussions of Russian politics and economics

--- has been that of transition

The ambiguity surrounding Russia’s Europeanness

- should thus not be discussed as a spatial issue, as it regularly is,

- but along its temporal dimension,

- as the country, which is perpetually seen as being in some stage of transition to Europeanisation.

- It is suggested that ongoing political debates about ’Russia’ are invariably tainted by this history,

- and a call is made for more reflection on how those debates themselves work

--- to perpetuate certain representations of Russia to the detriment of others

--- Such reflection may have the welcome effect of working against possible attempts to ’build’ a European identity

--- by drawing on the experiences and rhetoric of ethnicised nation building.

The question of where Russia fits in is a central component of contemporary discussions of the European security order

- and frequently their focus.

- It is the central part of most day-to-day deliberations over institutional particulars,

- such as the way to handle the expansion of organisations like the EU and NATO.

- It also permeates discussions of economic developments,

- not only where markets for such raw materials as petroleum and aluminium are concerned,

- but also the overall question of what is most often referred to as the transition of former communist economies.

When these developments come under the scholarly gaze, as they frequently do

- the result is usually pieces on the practical problems involved in

- how to handle Russia in one particular policy area,

- or discussions of which systemic forces that were at the heart of the breakdown of the Soviet Union

- and how these forces now work in favour of or against the inclusion of Russia in what is regularly named Western or European institutions

- Russianists also find a regular market for writings about the political struggles over what is named reform (or, again, transition)

- as they unfold in Moscow, St Petersburg and the amorphous Russian provinces.

One favourite Russianist argument, known to every policy maker and academic

- draws on the long history of struggles between:

--- Westernisers and Slavophiles,

--- modernists and traditionalists,

--- democrats and patriots,

- in order to demonstrate how metaphors of the past are very much part of the Russian political present (see Neumann 1995 for an example).

- During the Cold War, this argument would usually include parallels between the operating mode of Ivan the Terrible and Stalin

- At the beginning of the 1990s, parallels between Peter the Great and somebody often named tsar Boris were very much in vogue.[1]

Where Russia is concerned, then, the legitimacy and relevance of discussing how the handling of day-to-day questions of policy

- are influenced by references to the past are seldom questioned.

- Neither does one need an excuse for drawing parallels between 16th and 20th century rulers

- By extension, one should also expect there to be a scholarly debate about how European and Western metaphors of the past

- colour the handling of the question of where Russia fits in.

- Very few politicians and diplomats, and only the most ardent positivist scholar, would object to the general argument

--- that the way a political question has been variously discussed in the past

--- will impinge on the political business at hand.

- And yet, when it comes to the question of where Russia fits in,

--- there is very little by way of scholarly reflection on how this complex of issues has been handled previously.

What follows is an attempt to provoke a debate about how Russia has been constructed by (other) Europeans over the last 5 hundred years

- and what relevance these constuctions may have at present.

- Given the amount of relevant empirical material,

- the amorphous social setting of the discussions and

- the variations involved between different localities and language communities at any one given,

- the level of generalization must necessarily be high.

- From the end of the last century onwards, and particularly over the last 30 years, attempts have been made

--- to specify and justify a way of analyzing the social construction of reality at this level of generality

--- by using the concept of discourse.

- The relevant questions of theory and method need no treatment here

- However, since the word ’discourse’ is now being used in and out of season

--- to refer to everything from a friendly chat to the historical period of modernity in its entirety,

--- suffice it to say that discourse is social and political life understood in terms of its matrices.

It is a system for the formation of statements - a ’regime of truth’

- as well as ’the groups of statements that belong to a single system of formation’ (Foucault 1972: 1972).

- To apply the concept of discourse results in a displacement of what is being analysed and theorised,

- it works to replace the study of things which exist prior to discourse with an interest in the regular creation of objects (Waever et al. forthcoming).

- Working with a broad brush, I have made only feeble attempts at drawing up boundaries between different discourses

--- (such as the strategic) as well as between periods.

Since identity formation is context based

- identities cannot be pinned down as uniform over time,

- but will be in a constant state of flux.

- Different constructions will clash,

- as the most pervasive construction (or authorised version) is being reiterated, modified, challenged.[2]

’Russia’ will mean different things not only in different periods

- but also in different contexts during the same period.

- To take but one example, ’the Soviet Union’ meant something rather different

--- in Winston Churchill’s speech where he told the House of Commons

--- that it had been invaded by Hitler’s Germany

--- than what it meant in speeches he had held there before that event,

--- something different again in his dispatches about war aims written at about the same time, etc.

If the task at hand is to analyse representations

- as they have unfolded over half a millennium and

- in a number of languages,

- however, the differences which may be highlighted here

- can not be all those, which make a difference, but only the major ones.

A collective defines its selves in relation to its objects

- and so the creation of objects is simultaneously a negotiation of what kind of identity the self should have.

- The object in question here is Russia, and,

- whereas it is possible to postulate a number of discourses,

- in which Russia is created (in the sense of being socially constructed) as an object,

- the one singled out for discussion here is a European-wide one.

- The call for reflection on how Russia is being discussed is, therefore,

- also a call to pay attention to the role played by Russia in the formation of European identity.

- Since a discourse exists by and of its objects,

- the treatment of Russia is necessarily also an active part of the identity formation

- whereby Europe is being constructed and reconstructed (Neumann 1996).

__________________________________________

This article has evolved from papers presented to the Second Pan-European Conference in International Relations, Paris, 13-16 September 1995 and seminars at the Institut Universitaire de Hautes Etudes Internationales, Geneva and the European University Institute, Florence.

1. Given the question at hand, the point is not the legitimacy of drawing such parallels, but the simple fact that similar parallels between, say, a 16th century ruler such as Elizabeth the First and a 20th century ruler such as Ms. Thatcher are not a staple of scholarly debates about British policy. When such parallels are drawn, they are likely to be offered in lighthearted and frivolous spirit, very different from the matter-of-fact tone in which they may be found in a number of scholarly Russianist works. The matrices of the discussions are simply different.

2. To the methodological individualist it is, of course, a crucial question just who authorised the authorised version or, to rephrase, how a set of opinions come to be represented as facts. The standard social science procedures for determining this has been to look at the images held by politicians in office as well as senior servants, or to look at highly codified belief systems or ideologies. The focus here, however, is rather on what may be called the noise factor: Those representations which declare themselves most noisily in the discourse are held to be a worthy starting point for analysis, and it becomes an empirical and therefore variable question just how any one particular representation came into being.

Whereas some elements will be traced back to authors below, the focus here is firmly on the representations themselves.

http://www.eui.eu/RSCAS/WP-Texts/96_34.pdf

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The original posting was made at http://hojja-nusreddin.dreamwidth.org/102516.html