David Pinault, "IMAGES OF CHRIST IN ARABIC LITERATURE" (contemporary) - 1

This paper defines the ways in which contemporary Arab authors, both Muslim and Christian, employ the image of Jesus Christ as a literary figure in their creative fiction.

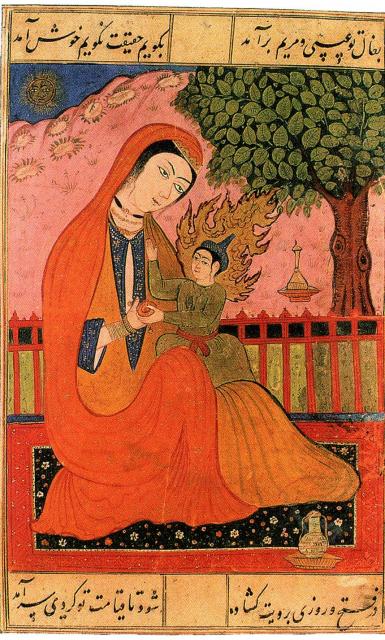

I begin with a brief survey of the medieval and early modern periods, noting the various stances with regard to Christ taken by Muslim authors, whether theological, polemical-disputational, or Sufi-devotional.

I then describe the secularization of the poetic figure of Christ in the period following the Second World War, and how this secularization combined with the popularization of Tammuz/vegetation-god symbolism, under the influence of T.S. Eliot's poetry and James Frazer's "Golden Bough", to result in an efflorescence of mythological imagery among Christian Arab and Muslim Arab poets alike.

Attitudes toward Jesus in the pre-modern period among Muslim Arabs, whether scholars or uneducated, depended on a combination of images drawn not only from the Quran, but from the Christian biblical New Testament, as well. A number of theological apologists, in attacking the divinity of Jesus, cite the New Testament directly. For example, the eleventh century AD Abd al-Malik al-Juwayni (in his "Shifa al-ghalil fi al-tabdil") shows scorn towards the New Testament Evangelists for not being careful enough in their biographies of Jesus to omit references to events such as the Scourging at the Pillar or the Crowning with Thorns, descriptions, as Juwayni asserts, which humiliate Jesus for the reader and diminish his claim to divinity.[1] Likewise Abu Hamid al-Ghazzali points to the description of Christ's Passion in the Gospel of Matthew, verses such as "Let this cup pass away from me" and "Father, why have you abandoned me?", and states that these passages necessarily are nothing more than evidence testifying against the divinity of Jesus, for they reveal him to have been a man, subject to human moods of weakness and doubt.[2]

Apologetic texts such as these are very critical of the Christians' Jesus; yet the image we encounter in works intended for a popular audience is far different.

A widely circulating genre of literature in the pre-modern period was the "Qisas al-anbiya" or "Tales of the Prophets", which drew on religious figures from the Jewish, Christian and Muslim traditions; many of these collections apparently represent transcriptions of legends recited for public audiences by marketplace story-tellers.[3] One such collection is the "Qisas al-anbiya" by Muhammad ibn Abd Allah al-Kisai, who, in his chapter on Jesus, creates an image of Christ as miracle-worker. One of al-Kisai's favorite techniques is to take a brief reference to Jesus from the Quran and expand it into a fully dramatized story; for example, al-Kisai employs Surah iii.49 from the Quran: "Behold, I shape for you out of the mud the image of a bird, then breathe upon it, and it becomes a bird, with the permission of God." From this brief Quranic reference al-Kisai creates a detailed narrative account of Christ's public ministry, and of how he first drew crowds to him in Nazareth by bringing images to life through miracles, and turned the crowds' skepticism to belief.[4]

For the more educated, however, Jesus was not only a worker of miracles, but also a guide to conduct, especially among the ascetic practitioners of Sufi mysticism. George Anawati describes the image of Christ that prevailed in Sufi texts: Jesus as a wanderer, clad in a plain woolen habit, living in the wild on a diet of berries and roots, accompanied by one companion, John the Baptist.[5] In various mystic texts Jesus also served as a model of conduct for the Sufi novice on the path of spiritual renunciation of all material objects. Following is an example from a thirteenth-century (AD) text, "Fawaih al-Jamal", written by the Sufi master Najm al-Din al-Kubra:

"It is said of Jesus, upon him be peace, that he was sleeping, with his head resting upon a brick, when he woke up suddenly from his sleep, and there was the Accursed One by his head. Then Jesus said to him, "Why have you come to me?" and Satan said, "I covet you." Jesus replied, "Accursed One, I am the Spirit of God. How are you able to covet me?" Satan said, "You have taken possession of some refuse of mine, and so I covet you." Jesus said, "And what is that refuse?" Satan replied, "This brick beneath your head." And then Jesus, upon him be peace, hurled the brick at him; and so Satan departed from him".[6]

Immediately following this passage, al-Kubra applies this exemplum to his personal experiences, where he describes how he followed Jesus' example in warding off temptations from Satan while concentrating on his mystic devotional exercises.

There is one final aspect I wish to note concerning representations of Jesus in the pre-modern period. The poetic image of Christ was at times manipulated by various governments for political reasons. The most noteworthy example is from the Crusades. In 1144 AD, Imad al-Din Zengi, atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo, announced a jihad against the Franks. In response, the court panegyrist Ibn Munir composed poems urging Zengi's son Nur al-Din to wage war against the Crusaders, as he says, "until you see Jesus flee from Jerusalem."[7]

In the same spirit of confrontation, the thirteenth-century Damascus historian Abu Shama made a pun on the Arabic name of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, "kanisat al-qiyamah", by calling it "kanisat al-qumamah" or "church of dung" or "filth".[8]

Such intolerance in fact is atypical, for the overriding image of Jesus in Islam is that of a prophet with a secure place in the Quran; but these quotations show how the poetic image of Jesus could be influenced by political developments - something which we will see reflected when we look at the modern period and post-Word War Two poetry in Arabic.

The disparate representations of Christ which I have cited, as miracle-worker and model for conduct, seem to have remained largely unchanged till the XX century, when 3 new trends combined to alter significantly the use of the figure of Jesus in Arabic literature.

The 1-st trend is defined by Mustafa Badawi as the Romantic era in early XX century Arabic poetry, when the poet was no longer either the spokesman for a given tribe or an artisan producing crafted verse for a royal patron. Instead, the poet of this period was free to seek a much wider audience.[9]

The Lebanese poet Khalil Jubran, writing at this time, used the poetic symbol of Jesus to reach a universal audience. Christ, for Jubran, became the example (in the words of N. Naimy) of the "ordinary man of ordinary birth, who has been able through spiritual sublimation to elevate himself from the human to the divine".[10] Though himself a Christian, Jubran deliberately intended a secularization of the figure of Jesus, so as to make him a symbol of interdenominational significance. This secularization represented a first step in making Jesus accessible as a poetic figure to both Muslim and Christian Arab poets.

The 2-nd trend in twentieth-century Arabic literature is one described by Selma Jayyusi,[11] in which Arab authors became exposed to the anthropological theories of James Frazer in "The Golden Bough", which (in the chapter entitled "Dying and Reviving Gods") relegates Jesus to the rank of one in a series of vegetation gods such as Tammuz and Adonis, and which attempts scientifically to expose the common mythological underpinnings of various world religions. Of even more importance for Arabic poetry was the use made by T.S. Eliot of "The Golden Bough", where Eliot applied Frazer's motifs of fertility-sacrifice and resurrection. The most famous example is his poem "The Waste Land", where Eliot describes lilacs bred

"out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Winter kept us warm...

Feeding a little life with dried tubers."[12]

Thus, with Jubran setting the example, and via the anthropological work of Frazer and the poetic work of Eliot, the Christ-image of sacrificial death and resurrection was made to transcend the boundaries of religious sectarianism, so to speak, and enter the world of myth. In this way - and this seems to have been particularly exciting to Arab poets from the 1950's on - Jesus could be claimed by all men as their own, as the symbol of a spiritual process underpinning all religions and all mythologies.

Finally, the 3-rd trend to note in this context is the increasing popularity of the concept of "iltizam or 'political commitment'" as a theme in contemporary Arab literature. The term "iltizam" first gained currency in Arab literary circles around 1950, when it was used to translate Jean Paul Sartre's concept of engagement; iltizam then quickly ousted what had been the prevailing current of individualistic romanticism between the two World Wars. For many Arab poets of the '50's and '60's, the degree of iltizam manifest in a poem determined its worth; the concept became espoused by various Arab literary critics who considered themselves partisans of Marxism and socialist realism.[13]

Two of the poets I mention below, Badr Shakir al-Sayyab and Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayyati, both applied this theme of iltizam to poems employing the image of Jesus. In this next part of my discussion, I will cite my translations from the poetry of contemporary Arab authors who make use of the figure of Christ as a poetic image. Most of these poems have not previously been accessible in English.

My first example is by the Iraqi Abd al-Wahhab al-Bayyati, from a collection published in 1968 called "Ashar fi al-manfa (Poems in Exile)":

And his eyes filled with tears

and he said to me:

Jesus

passed by here yesterday, Jesus.

His cross: two tree-limbs, green,

blossoming.

His eyes: two stars

His appearance: that of a dove.

His bearing: that of songs.

Yesterday he passed by here

and the garden flowered

and children awoke, abounding in grace

and in the heavens

the stars of night were

like bells

like crosses

drowned in my tears - the sorrows were

our way to love and oblivion;

And our green earth in her birth-pains

weakened by wounds

was dreaming of lilies and the morning

dreaming of a thousand Jesuses who will bear

their cross in the darkness of prisons

and who will be numerous

and who will give birth

to progeny who will sow God's earth with jasmine

and make heroes and saints and make revolutionaries.

* * *

And his eyes smiled like the morning

and the children awoke, abounding in grace

And in the sky

there was an angel, with wings the color of green

opening in a lamp the door of night.[14]

In this poem, Bayyati describes Jesus as the model of the suffering political revolutionary and illustrates the theme mentioned earlier of iltizam-commitment.

In the writings of the literary critic Rita Awad we find another example of the connection between politics and the mythological secularized image of Christ. In a recent work entitled "Usturat al-mawt wa-al-inbiath fi al-shir al-arabi al-hadith (The Myth of Death and Resurrection in Modern Arabic Poetry"), she describes the Palestinian fedayeen as the embodiment, as she says, of "Tammuz, and Christ, and Khidr, and Husayn",[15] thus she combines images of death and sacrifice from Muslim, pagan, and Christian religious traditions.

The image of Christ in twentieth-century Palestinian poetry is treated at length by Stefan Wild in an essay entitled "Judentum, Christentum und Islam in der Palastinensischen Poesie". Wild notes that in modern Palestinian poetry questions of religion tend to be subordinated to political issues of resistance and national independence; religious motifs from both the Christian and Muslim traditions are thus incorporated into a secular nationalist literature.[16] An example of such syncretism can be found in the poetic verses sung at mawlid-festivals in Palestine in the period following the first World War:

Jesus and Muhammad, in the cosmos of men, are the two

brightest stars-how beautiful are the sun and the moon!

In this period the image of Christ was also employed in Palestinian poetry to express the growing Arab resentment against Jewish immigrants to Palestine. Wild observes the combination, in certain Arabic poems of the Mandate period, of anti-Jewish sentiments from Islamic countries with the much more virulent anti-Semitism of Christian Europe.[17] One example is a poem from the Mandate period by Wadi al-Bustani, in which the poet adresses the Jews en masse and condemns them for the murder of Jesus. Al-Bustani presents the figure of Christ in this poem as follows:

...A king came to you, a king came,

who woke the dead from the grave to life.

To your shame you demanded his death

and the shame goes on clinging to you now.

Al-Bustani continues this classic Christian anti-Semitic formulation with the threat:

You are no more than objects of slaughter for our swords

And nothing more than straw for our fire.

In such poems, as Wild remarks, political anti-Zionism becomes indistinguishable from anti-Jewish hatred.[18]

In the period since 1948 the image of Christ has appeared frequently in Palestinian poetry. A qasidah written in 1952 by Misbah al-Abudi establishes what may well have been the first comparison in poetry between the figure of Jesus and that of the Palestinian refugee.[19]

More recently Kamal Nasir (one-time adherent of the Baath party and, until killed in Beirut in 1973, a member of the Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization) articulated what Wild describes as "a kind of poetic theology of hatred",[20] which Nasir expressed in his poem "Unshudat al-haqd (The Song of Hate"). According to Nasir, Christian concepts of love and peace are worthless until Palestinian nationalist goals are realized. In this polemical poem, Nasir also addresses a speech to the figure of Christ directly, warning Jesus to flee Israel, if He chooses to identify Himself with Western imperialist powers:

If you belong to them, Son of Mary,

then go back to their dwellings.

What we see then in the modern Palestinian poetry cited by Wild is the frequent appearance of the image of Christ in a highly politicized and secular context.

In many of the modern Arabic poems treating of Christ, however, the poet does not threaten political enemies with violence; rather, he identifies with Christ in His sufferings as a victim of violence. Bayyati offers a fine example of such identification in his poem "Ughniyah ila sha'bi (A Song to My People)":

I am here, alone, upon the cross.

They devour my flesh, the men of violence of the

highways, and the monsters, and the hyenas.

O maker of flame,

My beloved people

I am here, alone, upon the cross.

The young assail my garden

and the elders revile

my shadow, which spreads its palms out to the stars.

That it might wipe away the sorrows

from your saddened countenance.

O my imprisoned people,

you who lift up your brow

to the sun while it raps upon the gates

with dyed garments,

I am here, alone, driving drowsiness

from your exhausted eye.

O maker of flame

My beloved people.[21]

Whereas the Muslim apologists of the pre-modern period such as Juwayni and al-Ghazzall had attacked the divinity of Christ because of his suffering and humiliation, Bayyati identifies with this secularized Jesus precisely because of Christ's passion and suffering, a suffering which Bayyati takes on himself and accepts on behalf of his people.

My next example of Arabic Christ-imagery is from Yusuf al-Khal, a contemporary Christian Lebanese poet, who also identifies himself with the sufferings of Jesus in a poem entitled "Al-Shair (The Poet"):

I fasten my eyelids on the sun;

My eyes are now exhausted.

I am suspended, hung with nails;

I bleed, and the palms of my hands are upon the horizon.

For I am crucified,

but tomorrow I rise from my tomb.

Do you doubt? Look!-there am I, all of me

and here are the marks of my sufferings

and here is my blood

and the whispering of my steps upon the earth.

And when flowers break forth

and the fruit ripens,

I will be here;

Or when loveliness bathes in

the tranquility of the body

And the eyes become drunk for all eternity.

And when you ascend the mountain summits

even if but rarely,

you will see me there.

You will embrace me;

your two hands will touch me;

You will become with me

He who created you.[22]

Here again, as with Bayyati, we see the poet taking on himself the sufferings of Christ; but here there is a greater note of serenity, in the certainty of a resurrection to come.

My final poem is from the work of the Muslim Iraqi - Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, from his diwan "Unsudat al-Matar (Song of the Rain"). I quote here a few lines from his poem "Al-Masih bada al-Salb (Christ after Crucifixion"):

Warmth touches my heart

My blood runs into its moist earth.

My heart is the sun, for the sun pulses with light;

My heart is the earth, pulsing with wheat, and blossoms,

and pure water.

My heart is the water, my heart is the ear of corn:

Its death is the resurrection; it gives life to him who eats.

...I died by fire, darkness scorched my soil,

yet the god endured.

...I died that bread might be eaten in my name,

that they might plant me in due season.

How many lives I shall live!

For in each furrow of the field

I have become a future;

I have become a seedling;

I have become a generation of men:

In every man's heart is my blood,

a drop of it, or more.[23]

This imagery evokes at one and the same time the Christian Eucharist and vegetation myths of Tammuz. As a fertility god, Jesus can describe his heart as an ear of corn and his body as a sacrifice to the crops, ready to enrich the soil "in due season". And as the god of the Christians, Jesus can offer himself on the cross and institute the commemoration of his sacrifice in the breaking of bread. Thus, there is a perfect fusing of Tammuz and Christ imagery in these balanced verses:

"I died that bread might be eaten in my name,

that they might plant me in due season".

In conclusion, then: Contemporary Arabic poetry represents a break with the depiction of Jesus in pre-modern literature, via a process of secularization and mythologizing. The result is that Muslim and Christian Arab poets alike have felt free to use the figure of Christ as a secular symbol of political struggle and social commitment, as an image of suffering undertaken on behalf of one's people, and as a vegetation god of myth, with whom the poet participates personally both in death and resurrection.

__________________________________________________

I wish to thank Professor Roger Allen of the University of Pennsylvania for his continual support and encouragement in the preparation of this paper. A preliminary form of this article was read at the annual conference of the Middle East Studies Association in San Francisco on November 30, 1984.

__________________________________________________

"Die Welt des Islams", New Series, Bd. 27, Nr. 1/3 (1987), pp. 103-125

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1570518

Начало. K Продолжению: http://hojja-nusreddin.livejournal.com/2310496.html

Bonus: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus_in_Islam