Greasepaint and Pancake Mitts

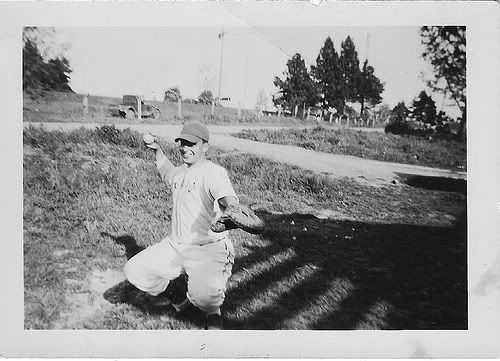

(My Dad catching when he was 17, in 1948)

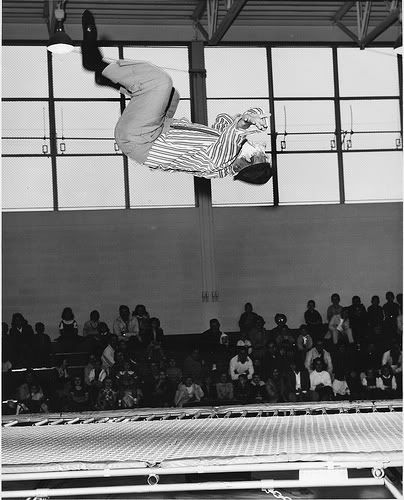

As a child, two objects in our storage closet fascinated me: my grandfather’s catcher’s mitt, and my dad’s clown makeup kit. My grandfather’s mitt was the old pancake style mitt common in the 1920s, thickly padded with no flex or even a pocket. You needed two hands to catch the ball. My Dad was career military, but started a clown act on the side to perform at events around the Air Force base. His clowning partner was a teenager named Lefty, the son of the base commander. Lefty grew up to be a fighter pilot and was shot down and killed over Vietnam. When my Dad dreamed about him, Lefty was always in clown makeup, doing cartwheels.

(My Dad doing his clown act.)

My grandfather taught my Dad to catch. Back in the 40s in the Pacific Northwest, baseball wasn’t something you watched, it was something you did. There were hundreds of unaffiliated minor league and semi-pro teams scattered across the county. Indian Reservations had their own leagues, and so did prison systems. The semi-pro team in my Dad’s town (Tigard, Oregon) was sponsored by the local paper mill. They needed a catcher, and he was the catcher on his high school team, so he got paid to play baseball at age sixteen. What could be better than that?

When I started my youth baseball career, I was a second baseman. By my third year, my Dad converted me into a catcher. He geared me up, and took a wooden bat and rapped me on the helmet, and smacked my shin guards and poked me in the chest protector to prove that I was safely armored. (Not entirely true, as any catcher will tell you. Nothing’s quite as unpleasant as taking a foul tip in the bicep.)

I didn’t have a great arm, but it was accurate and I had a quick release, and even though my league allowed leads and stealing on the pitcher I gunned most base runners down. My throw was always knee high, and on the first base side of the bag. I had good hands, and loved a play at the plate. My league didn’t require that the runner slide into home, and they often tried to take me out. But I had all the gear on, and became adept at applying a tag between their legs. At which point their forward motion came to a complete halt. I don’t know if that was entirely fair, but a catcher’s got to learn to protect himself and the plate.

The Christmas before my son Emmett’s AA season he received a box from my Dad. He opened the box to find a fine catcher’s mitt, a helmet, shin guards and a chest protector. Emmett played a lot of positions through AA and AAA, but as his manager I discovered that other teams scored less when Emmett was behind the plate. His manager on the all-star team, Marcelo, seemed to come to the same conclusion. When the Albany 11 year old all-stars went on their title run last season to capture the Northern California State Championship, Emmett caught 69 out 72 innings. When he was younger and people asked him what position he played, he’d rattle them off: shortstop, pitcher, centerfield, catcher. But now when people ask him what he plays, he tells them he’s a catcher.

(Emmett catching.)

Like most baseball fans, I don’t mark the arrival of spring by the appearance of daffodils, or robins, or the Easter Bunny. Spring comes with Opening Day. But for both the Albany Little League and the Major Leagues, there was a pall over the new season. As much as I was looking forward to managing this year, I felt a deep pang knowing I wouldn’t be seeing Fred Oyle out on the fields. The first weeks of the Major League season seemed shadowed by death: the promising young pitcher for the Angels, Nick Adenhart, was killed in a car accident mere hours after I’d watched him shut down the A’s; the great, goofy rookie sensation of 1976, Mark Fidrych died at age 54; and longtime announcer for the Phillies, Harry Kalas, died preparing for a game. Maybe I felt the sting a little more acutely than most; my father died on April 2nd.

I wonder if the clown in my father had wanted to go on April 1st, and the parent in him overruled that. Maybe April Fool’s Day wouldn’t be the best day for your children to get that call. I had talked to him two days before he died, telling him that Emmett was umpiring games this year. My Dad had umpired hundreds of games when I was growing up, and I knew he’d be pleased to hear that Emmett was following in his path.

As a writer and a baseball fan, I have strong opinions about baseball writing, and it is my strongly held opinion that Roger Angell’s essay “The Web of the Game” is the greatest piece ever written about the game. It’s a story that unfolds slowly, as Angell sits in the stands next to the Yale pitching coach before an NCAA regional championship pitting Yale against St. John’s. Angell masterfully parcels out the details, and you’re surprised and pleased to find out that Yale’s starting pitcher is the young Ron Darling, who would go on to pitch for the Mets in the 1986 World Series. And the starter for St. John’s was the young Frank Viola, who would go on to become the best left-handed pitcher of the 80s, and the ace of the 1987 Champion Twins. I won’t spoil the narrative for you, but the game that unfolds is widely considered to be the greatest college baseball game ever played, and the 90 year old pitching coach for Yale is none other than the legendary Smokey Joe Wood, who pitched for the championship Boston Red Sox at the turn of century.

That essay has been on my mind since my father died. It’s about how the game gets passed down through the years, from generation to generation. How you can know the past and see the future through the game. Baseball is, in every real sense, the legacy that I have handed from my father to my son. What Fred Oyle gave to his son, Alex. The future that we could see for Nick Adenhart; the memories we had of Mark Fidrych.

(My Dad and Emmett a couple years ago.)

I haven’t dreamed about my father since he died. I don’t know if he’ll come to me in dreams wearing clown makeup, doing flips on the trampoline. But when I think of him, I think of playing catch with him in the back yard - that simplest pleasure of the ball going back and forth, the ritual and rhythm of it. My two and a half year old daughter, Matilda, loves baseball, loves seeing the games and Emmett’s teammates (“It’s Arlo! Jack is my friend!”), and we’ve already started with a Nerf ball and bat. But baseball’s not her first love. On Saturdays she goes to the circus school on our street in San Francisco. She’s learning the trapeze.

(Matilda on the trapeze. Emmett's in the background wearing the Venture Brothers shirt.)