Watchmen (2009)

Directed by Zack Snyder

Screenwriters: David Hayter and Alex Tse

Images found via aintitcool.com, iwatchstuff.com, watchmencomicmovie.com, and the official WB Watchmen site.

Note: I haven't read the comic books, so all commentary is directed at the movie and not necessarily the print series.

Before I saw Watchmen, I had two conversations regarding its merits with different representatives of the teenage male demographic.

Conversation #1:

"I saw Watchmen over the weekend."

"Oh, was it any good?"

"It's overrated. It was basically all violence and sex."

"But you're a teenage guy, there can never be enough sex!"

Conversation #2:

"So who's seen Watchmen?"

"I have."

"Oh, was it any good?"

"Yeah, it was really good."

"I heard there was too much sex and violence."

"Nah, it was fine."

From these two sterling examples of movie criticism, I wasn't quite sure what to expect.

Watchmen opens with a startling dissonance: an absurdly slapstick, gruesome battle is filmed in slow-motion, punches and throws aimed in weird, perfect counterpoint to an undeniably happy orchestra. It's meant as artistry and also as a means to cheapen the violence, to make it seem laughable. I understand that this is the ironic point of Watchmen, that superheroes are not heroes, that the violence they utilize operates not under a code of nobility but as part of the same savage core all humans possess.

It doesn't mean I have to like it.

Watchmen is a confused, discordant movie that attempts to unite two themes (life is a joke; life is a miracle) but never quite succeeds. From the opening credits -- a jarring, gloomily beautiful alterna-history that threads superheroes into its Cold War-centric fabric -- we're introduced to a grim world where Nixon has been elected for his third, no, fifth term, and ordinary citizens live cowered by the threat of the Soviets. Kissinger and Buchanan make cryptic prophecies on grainy television about the threat of nuclear war, while scientists-cum-politicians adjust the "Doomsday Clock" -- it marks how close the Earth is to self-extinguishing -- at rapidly diminishing intervals.

Everyone's worst nightmare.

There's a plot or two (or three or four), but essentially, the old guard of superheroes has wasted away, leaving a new, decidedly more cynical bastion to rise in its place. It doesn't really make a difference, however, because all superheroes, old and new, have been given a forced retirement, courtesy of Uncle Sam.

The old guard.

One night, a member of the old guard, the Comedian, is murdered, a victim of the opening scene's battle, and his murder brings together the remnants of the superheroes, dredging up bitter memories and forcing them to consider that they might be all be targets of a painful, purposeful execution. As a plot device goes, this isn't entirely original, but the movie seems to depend on its characters to provide narrative structure, to offer us all the conflict, antagonists, and twisted non-romance we can handle.

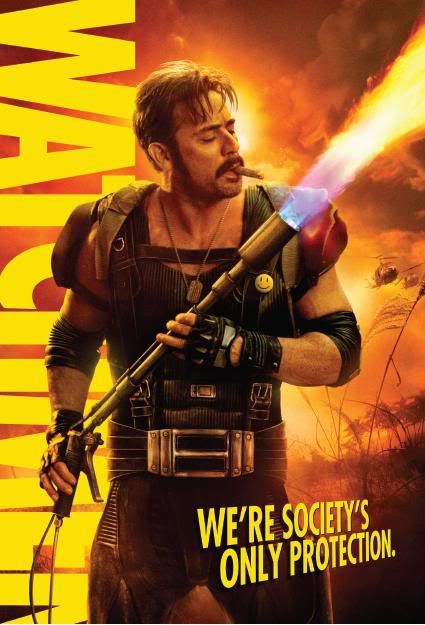

The Comedian in all his fiery glory. As for the type of protection he provides? Hm....

A good hour-and-a-half is spent stumbling through sequence after sequence of gruesome, bloody flashbacks, visceral proof of how depraved and disillusioned these super-beings really are. They're just manifestations of our own bloody natures, Watchmen reminds us repeatedly, just vicious humans with souped-up powers. If these are the type of people who are supposedly superior, our "guardians" who watch and prevent (and occasionally cause) crime, then what does that make us? And who watches them?

It's all good material to chew on and serves to distract the audience from wondering for roughly two-and-a-half hours what exactly is the connection between the impending nuclear holocaust and the demise of superheroes. Almost.

I give the narrative points for its unconventional choice of taking its cues from the Comedian's life story and how others reacted (or didn't) to his barbarity, rather than following the predictably gruff Rorschach (played by a eerie Jackie Earle Haley), who is fierce and insane and uncompromising, with a growl that could rival Christian Bale's Batman. I found the Comedian (deftly handled by Jeffrey Dean Morgan) a complex, horrible man, and with his death/life acting as a framework, the movie was made that much more watchable. Or unwatchable, depending on your tolerance for borderline-gratuitous (yes, yes, I know there was a point) violence.

All this gritty and grim bloodshed forces the fimmakers (obviously seeking some respite from the perpetual gloom and doom) to take a quick jaunt to Mars, where we get a first glimpse of the "life is a miracle" idea. However, this small moment of peace doesn't last long, and it's ironic that it takes a silent and lifeless environment to see the better sides of life. We're quickly transported back to Earth, which is relentlessly dark and hopeless, populated by "whores and vermin," as Rorschach likes to spout in his gravelly, absolutist voiceovers that did nothing to assuage how weary I was with all this angst.

The torturous, almost soap-operatic quality of the Dr. Manhattan--Silk Spectre II--Nite Owl II not-love triangle I could have done without, but fortunately, the acting overcame the cheesy lines and brought life to these otherwise very defeated characters. Dr. Manhattan (Billy Crudup), a giant, generic blue take on the scientific-experiment-gone-wrong archetype, was coolly impervious; Silk Spectre II (Malin Ackerman, in a convincing performance) is sexy, sweet, strong, yet vulnerable -- in other words, every man's dream girl (I was somewhat surprised that she received first billing in the credits); and Nite Owl II (acted with charming boyishness by Patrick Wilson) is a puzzled Everyman endowed with crazy gizmos and gadgets. He's Batman gone to seed. In fact, every character is a reference to the gilded superheroes of the Marvel and DC golden age; even the sleek, powerful Ozymandias (Matthew Goode) recalls Bruce Wayne to mind.

Why hello there, Willy Wonka Ozymandias/Adrian Veidt.

Rorschach is almost a caricature of the masked, dangerous vigilante, but he brings an interesting philosophy to this tale, for in his words, he "lives life without compromise and walks into the shadows." His uncompromising nature poses a question, late in the movie: Is peace based on a lie worth it? But this question is disappointingly answered, if at all, and while I don't fault Watchmen for tacitly condoning something I disagree with, the real fault in Watchmen is the attempt to weave together multiple themes and address each one with depth and clarity. (This might be because it's an adaptation of a comic book series, which has far more issues to explore each subplot and theme it presents.) The filmmakers attempt to impress upon us that life is a miracle, but in the end, as Rorschach's journal threatens to expose the truth, we see that really, all the drama and anxiety and sacrifice was for naught. Life, as the Comedian liked to point out, is one big joke.

Willy Wonka's chocolate factory Adrian Veidt's secret hideout.

There's a song playing near the end of the movie, as two superheroes battle the wintry elements of Antarctica in a flimsy helicopter-cum-battlestation: " 'How can we get out of here,' said the joker to the thief!" That's exactly what I asked myself, after vaguely recognizing and ignoring the metaphorical aspects of the joke life plays on us and how it steals away our spirit. I'd been asking myself when this would end for over an hour; I was weary and exhausted from the neverending montage, the insistent message that "humanity's savage nature will lead to its annhilation."