Fantasian

Sakaguchi Shrugged

Sometime after purchasing my latest computer, a Mac, I discovered that I could receive a few months of Apple Arcade for free, which I used to play the one title on the gaming service that appealed to me, Fantasian, a production of Mistwalker, a studio founded by Hironobu Sakaguchi, creator of Square, now Square-Enix’s, fabled Final Fantasy franchise. Mistwalker published the ambitious title in two parts in April and August 2021. What could go amiss, given Sakaguchi’s repertoire and a soundtrack from Nobuo Uematsu, with whom he worked on most Final Fantasies?

The story focuses on Leo, a young man who becomes amnesiac upon entering an alternate universe called the Machine Realm. Cue anyone who has played many other Japanese RPGs to roll their eyes and lose interest, with characters like Kina also unable to remember their past. The game tracks the story as players advance, with intricate backstories of the various characters revealed through colorful scenes. The atmosphere of Fantasian is fascinating as well, and occasional humor abounds. However, the amnesia cliché plagues the game, some terrible plot direction and weird moments abound, and common JRPG illogic comes at a few points, for instance, with a dragon that gradually pushes your party back to a cliff until they fall off and get a Game Over, despite how the party could have just rushed back forward when said boss didn’t move at all. Other banal aspects, like the repeated need to jump through a single wormhole, envenom the narrative, accounting for a lackluster plot experience.

The translation is legible, with no spelling or grammar errors; however, there are a few niggling points like some Japanese left in, using “their” for a man, unoriginal terms like “the Big Bang,” terrible character names such as Ez, and so forth.

Fantasian features randomly encountered turn-based battles where the player’s party of up to three active characters faces several enemies. Each character can attack with their equipped weapon, with players able to touch whatever Apple device they’re using to guide the path of their attack to the enemy and release it to execute. They can also use MP-consuming magic that can affect a range of foes, a single enemy, or piece multiple enemies in a straight line or curve. In an oddity for a Japanese RPG, no traditional option to defend to reduce damage exists; however, a few characters can do so for some MP. Seriously, Mistwalker?

Other options include using consumable items, with the game’s limit being far more generous than most RPGs prior, capping out at 999 for each type. The player’s party can also escape, which for me worked all the time except once. A turn order meter at the bottom of the screen shows when the player’s characters and the enemies take turns, which is always welcome in any turn-based RPG. When the player acquires more than three playable characters, they can swap frontline party members with anyone in reserve without wasting turns, another welcome feature.

Leo's party is apparently alien to the idea of moving back forward when pushed to a cliff.

Many foes have elemental strengths and weaknesses, with analyze magic revealing them, mercifully and permanently remaining in effect once used on a specific enemy type. However, players won’t have access to many elements throughout the first part of the game, and standard elemental attack consumables barely scratch even foes weak versus them. A later accessed feature is the Tension gauge, filled through dealing and receiving damage, which, when filled, allows characters to use ultrapowerful limit break-esque skills that can massively damage all foes or fully restore all who are on the frontline. Unfortunately, the Tension gauge oddly doesn’t remain full between encounters should players wish to save it for boss fights.

A notable feature accessed early is the Dimengeon, which, when activated, “absorbs” enemy encounters consisting of foes the player has already defeated (skirmishes containing adversaries players haven’t battled yet they encounter standardly). Once the Dimengeon overflows, the player faces all enemies contained within, though luckily, not all at one time, with backup foes replacing those which they off. Appearing alongside adversaries are nodes representing bonuses like increased attack or defense for the party that they can slice through with standard attacks or special skills to activate. Victory in these battles, like regular encounters, net all on the frontline and in the vanguard still alive experience for occasional leveling, plus money and items, with these rewards multiplied in the Dimengeon.

Defeat results in the option to restart the lost battle from the beginning (pointless since it doesn’t decrease difficulty, with encounters like boss fights being incredibly lengthy as well) or reload the last saved file. Around the middle of the game, characters receive skill trees into which they can invest points obtained through leveling for stat increases, new skills, and empowerments to current abilities; unlocking those for specific allies requires the completion of certain sidequests. Some passive effects can be nifty, like counterattacking and stealing items while standardly attacking. However, unlocking paths to many nodes requires special grimoires whose discovery may necessitate using a guide.

Bosses are another ballpark. Long cutscenes often precede them, and while the player can fast-forward through them, it’s a lazy substitute for an option to skip the scenes directly to the following fights. Many bosses have multiple appendages that the player can lop off to prevent attacks that can easily slaughter their party. Skills can boost character attack and defense, not to mention create barriers that can absorb damage until they break. The player can also decrease enemy attack and defense, but skills to reduce agility often fail against most bosses. One character, Ez, can mix items to increase the frontline characters’ attack, defense, and speed.

Some boss battles are enjoyable yet overshadowed by countless unfair conflicts. For instance, a dragon can push the player’s characters to a cliff until they fall off and get a Game Over. Another, when getting low on health, creates a field that consistently curses the party, nullifying healing. A later one, which made me rage-quit the game, has the boss enemy constantly summoning wolves that can slaughter your characters and get multiple turns before them. Many of these battles also mandate a story character be on the frontline, with no chance to swap them out.

Despite grinding for hours to increase levels and obtain new abilities and bonuses from the skill trees (a process that quickly became herculean), that barely dented said boss, despite my party having the best weapons and armor available then. Other mechanics contribute to the surefire failure of these conflicts, like the difficulty of getting deceased characters back on their feet if they die; if all frontline members perish, it’s Game Over, with no chance to use backup allies at all. Given the minimal margin for error against bosses and the sheer length necessary to take them down, they seemed like walls preventing me from advancing the plot, where fighting them felt like a chore to the point where I had enough.

Despite grinding for hours to increase levels and obtain new abilities and bonuses from the skill trees (a process that quickly became herculean), that barely dented said boss, despite my party having the best weapons and armor available then. Other mechanics contribute to the surefire failure of these conflicts, like the difficulty of getting deceased characters back on their feet if they die; if all frontline members perish, it’s Game Over, with no chance to use backup allies at all. Given the minimal margin for error against bosses and the sheer length necessary to take them down, they seemed like walls preventing me from advancing the plot, and fighting them felt like a chore to the point where I had enough.

Control has many positive aspects, such as in-game maps (although a mini-map on the main gameplay screen would have been welcome, given the need to slide open the menus to view them), a fair save system, easy menus, some functional touchscreen features (though my Apple Pencil didn’t always work at its best), sensible pathfinding when moving Leo through towns and dungeons, and the eventual ability to fast-travel among visited points in cities and dungeons. However, many blemishes exist, like the mentioned inability to skip cutscenes straight to bosses, no suspend saving, the vague direction at many times (especially in sidequests), the unusual difficulty of getting onto the overworld, some puzzles necessitating external references to get past, and even rare crashing. Ultimately, Fantasian often feels like a quality-of-life nightmare.

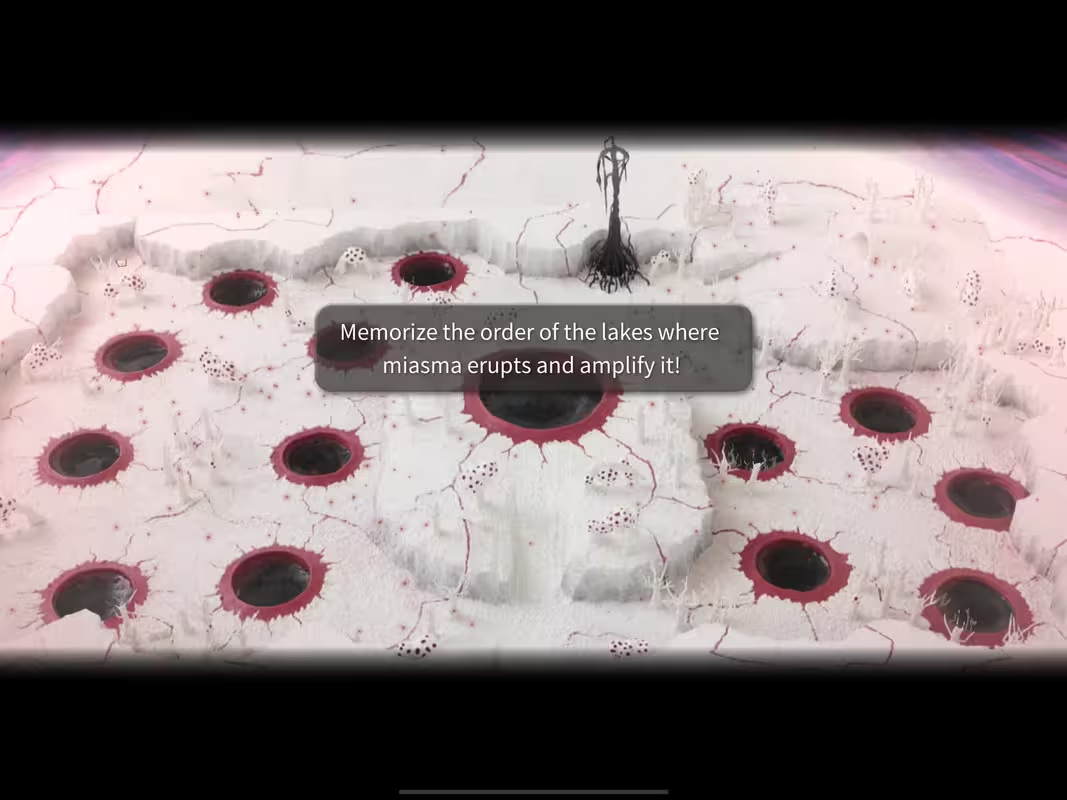

Good luck getting past this without taking a screenshot and sticky tabs, unless you have an eidetic memory.

Nobuo Uematsu provided the soundtrack, which is all-around solid, with its diverse melodies worth listening to on Apple Music, but where exactly was the music in the game? Too many places either have no musical accompaniment whatsoever or over-rely upon ambiance. The sound effects are fitting, and there’s no voice acting to worsen the aural aspect, but players won’t miss much if they listen to other music while playing.

Visually, Fantasian utilizes handcrafted dioramas for its scenery, with the various environs looking beautiful and colorful, with nifty effects such as the camera panning whenever the player traverses beyond the edge of paths. Furthermore, the character models, CG cutscenes, enemy designs, battle effects, animation, framerate, and weather effects are smooth. However, some blurriness and pixilation abound in the standard graphics, along with lazy telekinetic attack animations by the player’s character and enemies, many reskinned foes, and some occasional recycling of scenery. There also comes a speedbump where you must remember the order of springs erupting from a vast top-down view; however, when choosing the correct order, you deal with the constant camera changes that can throw off your orientation.

Visually, Fantasian utilizes handcrafted dioramas for its scenery, with the various environs looking beautiful and colorful, with nifty effects such as the camera panning whenever the player traverses beyond the edge of paths. Furthermore, the character models, CG cutscenes, enemy designs, battle effects, animation, framerate, and weather effects are smooth. However, some blurriness and pixilation abound in the standard graphics, along with lazy telekinetic attack animations by the player’s character and enemies, many reskinned foes, and some occasional recycling of scenery. There also comes a speedbump where you must remember the order of springs erupting from a vast top-down view; however, when choosing the correct order, you deal with the constant camera changes that can throw off your orientation.

Finally, I can’t accurately calculate total playtime since I couldn’t complete the game yet logged 56 hours before I rage-quit, which was more given all the time I wasted on losing boss battles. Referencing the internet, I discovered I still had a way to go before reaching the official end. While features such as Apple Arcade achievements theoretically add lasting appeal, I didn’t enjoy the game enough to want to continue.

Overall, Fantasian is another RPG that shows tremendous promise, given the great ideas in many aspects, like the game mechanics, its aural and visual presentations also showing much polish. However, the experience sours as the game drags on, given the countless difficulty spikes, boss battles that feel like walls preventing players from advancing, the usability issues, the unengaging narrative, and the lackluster musical presentation, which is inexcusable since the soundtrack as I heard it on Apple Music is superb. Considering Hironobu Sakaguchi’s track record with the Final Fantasy series, Fantasian should have turned out far better (but to be honest, I don’t think the various series entries he worked on became accessible, let alone playable, to mainstream audiences until rereleases such as the Pixel Remasters, which he didn’t seem to be involved with), yet exemplifies what is still wrong with most Japanese RPGs. Thus, I will happily avoid anything Mistwalker produces in the future and am not looking back.

This review is based on 56 hours of gameplay without completion of the game on an iPad, up to the boss fight with Rudy.

RECOMMENDED?

NO