The most important figure in the history of Marxism...

...indeed, one of the most important figures in modern history - is not, in my view, Karl Marx. Karl Marx died as pretty much a failure; only eleven people attended his funeral. His attempt to establish himself as the guide and general of a disciplined group of revolutionary leaders - although it formed the pattern for most twentieth-century tyrannies, through the admiring imitation of Lenin - resulted in nothing more than a series of violent conflicts in the rising international socialist movement and his own total discrediting.

Move ahead 22 years, and take the best witness - the witness of an enemy. The rising Christian polemist and genius, GK Chesterton, sees no value in Marxism at all. He charges it with reversing the meaning of human life, placing food (the ultimate point of its insistence on production and distribution) at its centre, and reducing men to the level of cows. But he is clear on one thing: in spite of what he sees as its anti-spiritual and anti-intellectual nature, Marxism is widespread among intellectuals to the point of being a commonplace. This, mind you, is twelve years before an adventurer from the fringes of Russian Marxism launched his brutal bid to take over the immense, broken Russian hulk, and, in a few years, transformed his branch of Marxism from a local political movement into a world power. Lenin's immense success certainly drew to him everyone who was disposed to be impressed by success (or "the judgment of history", as they would call it); and to that extent it helped make Marxism a dominant feature in modern politics for as long as Soviet money could affect it. But Marxism - and this must never be neglected - was an important and popular heresy not just in Russia, but across the West, long before the rise of the Soviet Union - indeed, before anyone had ever heard of Lenin. We do not have to be surprised that it survived its fall.

Socialism is even older than Marxism and would have become a significant party or set of parties with or without old Karl's sectarians. The aim of Marxism from first to last was not to estabish itself as a political movement unlike any other, but to take over the larger Socialist area and "organize it" in the Prussian manner natural to the Prussian Karl Marx. The success it gained in this endeavour, even before Lenin, was by no means predictable, especially in England (Marx' main area of activity and the place where Chesterton observed his posthumous success), where every Socialist leader from William Morris to Keir Hardie was Christian, and the link between religion and workers' movements seemeed unbreakable. So what happened?

There is one person, it seems to me, who turns up in a central role in every important moment of the history of Marxism from the death of its founder to her own; a woman, what is more, who strikes me as having had all the political insight and capacity to deal with reality that Marx himself lacked. At every turn in his life, Marx made the wrong political choice, from his attempt to hijack the 1848 revolutions - that helped nobody but the reactionaries - to his belief that Prussia was going to annexate Austria after the victory of Sadowa, to his misguided commitment to the Commune of Paris - the suicidal last trashings of the defeated capital of a defeated nation. It is not often remembered that Marx earned much of his scarce income as a journalist, and frequently appeared as a commentator on European affairs on various American dailies. He was an Andy Capp of political commentators: before the race, he could tell you with certainty which horse would win, and, and, after, why it hadn't. Some of these "why it hadn't" accounts are really excellent: his account of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte's political rise and coup d'etat is a memorable piece of journalism. But it should also be, if Marx were capable of such a thing, an admission of defeat, and, what is more, of error.

Now take Marx' own daughter Eleanor. Nothing is more important in the history of Marxism than its historical alliance with the intellectual classes; but Karl Marx himself, though a remarkable writer and, in his private life, a lover of literature who made his children learn Shakespeare, did nothing whatever to establish any interest in his doctrine among the pullulating Victorian world of scribblers and artists of every kind. Eleanor Marx, on the other hand, was a central figure in English culture in the late nineteenth century, translating Ibsen and Flaubert, collaborating with William Morris, discovering the young GB Shaw.

It is part of her enduring legacy that each of these items represents not just serious achievement in and of itself, but an epoch in the history of English and Western literature. Flaubert and Ibsen were more influential than other and equally talented contemporaries; Morris dominates the landscape of English arts; and Eleanor's involvement in the theatre, through Ibsen (whose A Doll's House she staged privately, with herself as Nora and Shaw as Torvald) and Shaw, places her at one of the most significant revivals in theatre history.

It may surprise my readers, to whom "The West End" is naturally the greatest centre of theatre activity in the world and the ambition of every actor and producer, but Victorian London had little or no theatre worth speaking of. Matthew Arnold records the enormous impression made by the visit of a French company featuring the young Sarah Bernhard, when the Victorians first got the shock of a really ambitious, accomplished and intellectually demanding theatrical artform, such as London had long since forgotten. The next generation set out to establish a London high quality theatre in a positively crusader spirit; GB Shaw used to pester every writer of quality he knew, from Chesterton to Kipling, to write for the stage. (And by pester I mean pester. He would not leave them alone, even where he disagreed with their politics. To have brilliant literature written for the theatre was to him more important than to promote his own politics. Indeed, one suspects that where he was not successful, or only partially successful, he wrote himself what he had wanted other writers to; his Saint Joan, a positively extraordinary outburst from an atheist with an Irish Protestant background, feels a lot like the sort of thing he would have hoped Chesterton would write.)

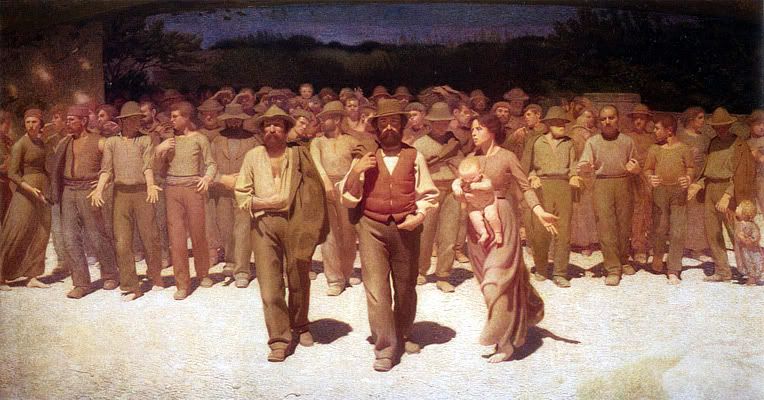

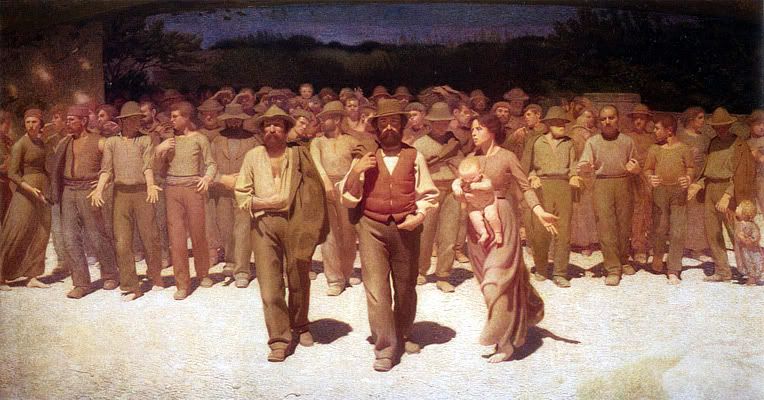

Eleanor Marx' contribution to this historical movement is not central, but it is significant; and it is typical of her instinct for everything that was vital in her time. Just as she saw the rise of the theatre in London, and in a larger way the increasing centrality of the intellectual class, as important fields of action, so too, at the same time, she took a central part in the epochal strike of the Bryant&May match-girls - an event that sanctioned the transition of English trades unionism from an affair of skilled workers to the masses of unskilled and neglected labourers who had thus far been allowed to be treated as less than slaves. It is the struggles of these masses of unskilled workers, more than anything else, that have given Marxism its political identity across the world, and above all its undeserved image of morality. When we think of Marxism, we are meant to think of marching masses of unskilled labourers, joined in one enormous negotiating forces, organized and ready both to hold back and to strike according to political need.

But while Karl Marx had a lot to say about labouring masses in the abstract, he had little to do with trades unionism as such. To him, it was a distraction from the path to revolution. His daughter, on the other hand, was there and did much of the hard work when trades unionism really conquered "the masses", the hundreds of thousands of really starving, really disinherited, really swarming labourers crowded at the gates of London in conditions we can scarcely imagine today. Without this feat of organizing the desperate, the swarming, the apparently unorganizable (a feat to which Marxist habits of mind must have been indispensable), trades unionism would have remained the concern of a comparative upper crust of already skilled workers, and would never have gathered the mass support that made Labour into a great party. It was the organization of the unskilled workers that propelled the Socialist parties, across Europe, to the centre of the political landscape, in less than a generation. In 1880, Socialism was a fringe grouping with almost no parliamentary representatives; in 1900, it had a massive presence in every decently elected Parliament in Europe, and where it was still suppressed - as in Russia - it had come to dominate the underworld. And the Bryant&May strike was a major episode on this path.

Indeed, the match-girls' strike represents a double milestone: not only a founding event in the history of mass trades unionism, but also the moment when the rising concerns of feminism broke out of the parlours of rich men's daughters in the West End and established themselves as a force among women of all classes. The alliance with feminism is another important feature of historical Marxism - amd Eleanor was there when it was first forged.

The very last significant thing that this remarkable woman did before she died (she left behind a set of edited minor works by her father that showed him in an unusual and interesting light, as historian and philosopher - one last act of filial devotion) was to translate a work by Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism. This is significant in all sorts of ways. First, it suggests an intuitive recognition of the coming significance of Russian Marxism. Eleanor's translations, with two exceptions, had been literary, not directly poitical - Flaubert and Ibsen - and of the two exceptions, one had been by a man she had loved and nearly married. (As we shall see, this is a matter of some significance.) To take this trouble on behalf of a little-known theorist, and a Russian to boot - Karl Marx had denied that Russia could experience a workers' revolution - suggests unusual interest.

It also places a firm underline under Eleanor's lifelong opposition to the Anarchist ideal, which Plekhanov's book is meant to demolish. Eleanor had left the Socialist League that she had had a large part in founding when, in an amusing reversal of common Marxist practice, it was taken over by an anarchist faction. The one point in which the devoted Eleanor - who had acted as her father's secretary when she was barely sixteen - did not innovate or reverse her father's practice was the rejection of anarchist theory and practice; and that was the one area in which Marx was indubitably right. They both saw that there was no future and no practicality in the fad of Anarchy, and in fact one of the most significant narratives of the nineteenth and twentieth century is the complete practical failure of this movement thus far. (Its latest incarnation, Ayn Randism, still does seem to have some life left in it, but I, personally, do not forecast any success.)

There is not one of the areas of significant force and success of Marxism - its connection with the intellectuall class, with mass trades unionism, with Russia, with feminism, and its tradition of organization and refusal of anarchist methods and goals - which does not bear Eleanor's signature. You don't need to love Marxism to see that this woman played a major part in Western history - a part that is still badly underrecognized and underappreciated. And unlike her father, some of her contributions - especially in the field of the arts and of trades union organization - were positive as well as significant. The great theatres of London owe her something, as does anyone who ever revelled in a performance by Lawrence Olivier, Alec Guinness, or Vanessa Redgrave. And one can't blame her for idolizing her father and thus promoting what was, remains, and will remain, a pestiferous and destructive philosophy.

In fact, I would place her next to her contemporary Nietzsche, not only for the practical importance and impact on modern politics of both, larger than that of any other intellectual; and not only because both clearly suffered from serious family-related issues and from a Prussian family heritage; but also because the ends of both, had anyone paid attention to their meaning rather than to their externalities, deliver the most shattering and devastating responses to the theories they had so brilliantly and effectively pushed. In their cases, their deaths really are a criticism of their lives; an unanswerable criticism.

As everyone ought to know, Nietzsche, the promoter of the ruthless and dominant Overman, suffered his final collapse - brought about by syphilis - when he saw an Italian cart driver belabouring his unfortunate horse cruelly with a stick. The Prussian philosopher threw the man off, embraced the abused animal's neck, and collapsed, weeping bitterly. From there he had to be taken to a house for the mentally ill; and he was never from then on in any condition to be released, until he died. The story comments itself, and I have no need to enlarge on it.

And Eleanor? Eleanor, interestingly enough, sounds a lot like Nietzsche - and like Nietzsche at his silliest - when she talks about Jesus Christ: a whiner, a loser, a bad example. She was, of course, brought up in an atmosphere of aggressive atheism, and in this as in everything else she never consciously broke with her father - even as in so many areas she innovated on or reversed his practice. One wonders how well her views went down with her English Socialist allies, of whom nearly every one was Christian or at least had Christian roots. However, atheism, whatever its relationship or lack thereof with English Socialism, certainly did bring her the man of her life.

Eleanor's life was dominated by three men: her father, whose work she so devotedly and capably continued; Hippolyte Lisagaray, the obscure French revolutionary and Commune of Paris survivor, whom she would have married - even against her father's will - had she not eventually come to agree with her father that Lisagaray was really too old for her; and Edward Aveling, whose name she took. The facts show that Eleanor (whom everyone called "Tussy" for some reason) was a devoted and passionate woman. When she fell in love with Lisagaray, she spent years breaking down her father's understandable opposition, before concluding by herself that marriage with a man 17 years older would not work; and even so, twenty years later she lent her translating work and the prestige of her name to have his Histoire de la Commune de Paris, 1871 published in English - hardly a small favour, whatever ideological excuses may be given.

If you look Eleanor up, you will most often find her, not under "Marx", but under "Aveling" or "Aveling Marx". That was the name under which she signed her work and her translations, and it seems clear that it was the name by which she wanted to be known. You may have noticed I refuse to do so, and that is not only because they never actually married, but because Aveling was the scum of the earth, altogether unworthy of her, and the direct and immediate cause of her death. And if this sounds too Victorian for words, I will answer that Aveling really was, in every way, the quintessence of the weak, womanizing scoundrel of Victorian fiction. The son of a Congregational clergyman, he experienced a revolt against his father's religion which evidently extended to all matters of financial as well as sexual morality. Notorious for borrowing and never returning even the smallest sums of money, suspect of having embezzled the funds of the Socialist League - it certainly was near-bankrupt when he left - he also is said to have had numerous affairs, without ever managing to father a child. He married an heiress, and left her after a couple of years without obtaining a divorce - he said, because she couldn't stomach his atheism; her friends said, because he could not get at her capital.

It was immediately after this that a vindictive fate, and a common faith in atheism, threw him in Eleanor's path. And how and why this hard-working woman, already expert in worldly matters beyond most of her contemporaries, so shrewd in political matters, so capable of forming lasting friendships and of gaining widespread affection - as was seen at her funeral - should fall for someone who literally was incapable of doing anything except writing atheistic pamphlets, is something that simply baffles understanding. As I said, Aveling had never obtained a divorce from his first wife; "Tussy" made the same mistake that many women have made before and since - she moved in with him without any formal bond. How she felt about the relationship is sufficiently shown by the fact that she took his name; and being herself loyal and devoted by nature, how was she to understand that he would prove the exact opposite?

One may speculate that Aveling might have been less destructive and damaging if he had, in fact, managed what he seems to have tried - married a rich woman and lived the life of a drone on her money. But I doubt it. There was something about his scoundrelism, like his compulsive habit of borrowing money - even from his poorest friends - and never repaying, that went beyond mere dishonesty and hints at some compulsive self-destructiveness, that would sooner or later have brought him down in some ruinous fashion, and probably have taken others with him.

Atheism led Aveling to Eleanor, and Eleanor led him to Socialism. Before they met, he had shown no interest in politics (he was a zoologist by training). Her enthusiasm quickly rubbed off, and he found there was plenty of work to do. To be fair to him, he did have a ready pen, and he co-authored all of Tussy's original writings on the workers' movement as well as publishing plenty in his own name. That represents a lot of work, and suggets that he was no drone - whatever Tussy's part in the origination of his writings.

In 1898 came the smash. Eleanor was now 43 - not old age as we understand it, but certainly a bad time for a woman to discover she has a younger rival. And not just a rival: Aveling, whose first wife had now died, had secretly married a young actress. (It had to be an actress, for the Victorian cliche' to be complete!) He briefly dumped Tussy for her, but came back when he found he had mortal kidney disease. She nursed him for a little while; then, one day, she falsified his signature on a prescription, bought cyanide from a chemist ("for a dog", said the falsified prescription), made sure she was alone in the house so that nobody should be able to rescue her, undressed, lay down in bed, and swallowed the poison.

That was it. The intelligent, far-sighted woman who had done so much to promote dialectical materialism, and who had actually done some considerable good in its service (though the goal remained disastrous), was destroyed, led to destroy herself with the most horrendous care and deliberation, by something that her father's philosophy treated as an epiphenomenon of socio-economic relationships, bound to wither and die when the new realm of freedom rose upon the earth: the love of man and woman, the exclusive relationship of marriage, the lifelong consecration of a man to a woman and a woman to a man. And may God have mercy on her soul, because no suicide ever had a higher heap of excuses for her sin.

My story began with the eleven lonely people at the burial of Karl Marx; it ends with a vast crowd at his daughter's cremation, speeches from no less than seven orators, and the preservation of her ashes as a kind of sacred relic by successive Marxist bodies (they were only interred in 1956, I believe). Aveling, who was dying of kidney disease, outlived her by only a few months, but he was (deservedly) treated as a pariah by every other Socialist in England, as well as by many people who were neither Socialists nor atheists, but who agreed that he had been the cause of his wife's death.

Move ahead 22 years, and take the best witness - the witness of an enemy. The rising Christian polemist and genius, GK Chesterton, sees no value in Marxism at all. He charges it with reversing the meaning of human life, placing food (the ultimate point of its insistence on production and distribution) at its centre, and reducing men to the level of cows. But he is clear on one thing: in spite of what he sees as its anti-spiritual and anti-intellectual nature, Marxism is widespread among intellectuals to the point of being a commonplace. This, mind you, is twelve years before an adventurer from the fringes of Russian Marxism launched his brutal bid to take over the immense, broken Russian hulk, and, in a few years, transformed his branch of Marxism from a local political movement into a world power. Lenin's immense success certainly drew to him everyone who was disposed to be impressed by success (or "the judgment of history", as they would call it); and to that extent it helped make Marxism a dominant feature in modern politics for as long as Soviet money could affect it. But Marxism - and this must never be neglected - was an important and popular heresy not just in Russia, but across the West, long before the rise of the Soviet Union - indeed, before anyone had ever heard of Lenin. We do not have to be surprised that it survived its fall.

Socialism is even older than Marxism and would have become a significant party or set of parties with or without old Karl's sectarians. The aim of Marxism from first to last was not to estabish itself as a political movement unlike any other, but to take over the larger Socialist area and "organize it" in the Prussian manner natural to the Prussian Karl Marx. The success it gained in this endeavour, even before Lenin, was by no means predictable, especially in England (Marx' main area of activity and the place where Chesterton observed his posthumous success), where every Socialist leader from William Morris to Keir Hardie was Christian, and the link between religion and workers' movements seemeed unbreakable. So what happened?

There is one person, it seems to me, who turns up in a central role in every important moment of the history of Marxism from the death of its founder to her own; a woman, what is more, who strikes me as having had all the political insight and capacity to deal with reality that Marx himself lacked. At every turn in his life, Marx made the wrong political choice, from his attempt to hijack the 1848 revolutions - that helped nobody but the reactionaries - to his belief that Prussia was going to annexate Austria after the victory of Sadowa, to his misguided commitment to the Commune of Paris - the suicidal last trashings of the defeated capital of a defeated nation. It is not often remembered that Marx earned much of his scarce income as a journalist, and frequently appeared as a commentator on European affairs on various American dailies. He was an Andy Capp of political commentators: before the race, he could tell you with certainty which horse would win, and, and, after, why it hadn't. Some of these "why it hadn't" accounts are really excellent: his account of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte's political rise and coup d'etat is a memorable piece of journalism. But it should also be, if Marx were capable of such a thing, an admission of defeat, and, what is more, of error.

Now take Marx' own daughter Eleanor. Nothing is more important in the history of Marxism than its historical alliance with the intellectual classes; but Karl Marx himself, though a remarkable writer and, in his private life, a lover of literature who made his children learn Shakespeare, did nothing whatever to establish any interest in his doctrine among the pullulating Victorian world of scribblers and artists of every kind. Eleanor Marx, on the other hand, was a central figure in English culture in the late nineteenth century, translating Ibsen and Flaubert, collaborating with William Morris, discovering the young GB Shaw.

It is part of her enduring legacy that each of these items represents not just serious achievement in and of itself, but an epoch in the history of English and Western literature. Flaubert and Ibsen were more influential than other and equally talented contemporaries; Morris dominates the landscape of English arts; and Eleanor's involvement in the theatre, through Ibsen (whose A Doll's House she staged privately, with herself as Nora and Shaw as Torvald) and Shaw, places her at one of the most significant revivals in theatre history.

It may surprise my readers, to whom "The West End" is naturally the greatest centre of theatre activity in the world and the ambition of every actor and producer, but Victorian London had little or no theatre worth speaking of. Matthew Arnold records the enormous impression made by the visit of a French company featuring the young Sarah Bernhard, when the Victorians first got the shock of a really ambitious, accomplished and intellectually demanding theatrical artform, such as London had long since forgotten. The next generation set out to establish a London high quality theatre in a positively crusader spirit; GB Shaw used to pester every writer of quality he knew, from Chesterton to Kipling, to write for the stage. (And by pester I mean pester. He would not leave them alone, even where he disagreed with their politics. To have brilliant literature written for the theatre was to him more important than to promote his own politics. Indeed, one suspects that where he was not successful, or only partially successful, he wrote himself what he had wanted other writers to; his Saint Joan, a positively extraordinary outburst from an atheist with an Irish Protestant background, feels a lot like the sort of thing he would have hoped Chesterton would write.)

Eleanor Marx' contribution to this historical movement is not central, but it is significant; and it is typical of her instinct for everything that was vital in her time. Just as she saw the rise of the theatre in London, and in a larger way the increasing centrality of the intellectual class, as important fields of action, so too, at the same time, she took a central part in the epochal strike of the Bryant&May match-girls - an event that sanctioned the transition of English trades unionism from an affair of skilled workers to the masses of unskilled and neglected labourers who had thus far been allowed to be treated as less than slaves. It is the struggles of these masses of unskilled workers, more than anything else, that have given Marxism its political identity across the world, and above all its undeserved image of morality. When we think of Marxism, we are meant to think of marching masses of unskilled labourers, joined in one enormous negotiating forces, organized and ready both to hold back and to strike according to political need.

But while Karl Marx had a lot to say about labouring masses in the abstract, he had little to do with trades unionism as such. To him, it was a distraction from the path to revolution. His daughter, on the other hand, was there and did much of the hard work when trades unionism really conquered "the masses", the hundreds of thousands of really starving, really disinherited, really swarming labourers crowded at the gates of London in conditions we can scarcely imagine today. Without this feat of organizing the desperate, the swarming, the apparently unorganizable (a feat to which Marxist habits of mind must have been indispensable), trades unionism would have remained the concern of a comparative upper crust of already skilled workers, and would never have gathered the mass support that made Labour into a great party. It was the organization of the unskilled workers that propelled the Socialist parties, across Europe, to the centre of the political landscape, in less than a generation. In 1880, Socialism was a fringe grouping with almost no parliamentary representatives; in 1900, it had a massive presence in every decently elected Parliament in Europe, and where it was still suppressed - as in Russia - it had come to dominate the underworld. And the Bryant&May strike was a major episode on this path.

Indeed, the match-girls' strike represents a double milestone: not only a founding event in the history of mass trades unionism, but also the moment when the rising concerns of feminism broke out of the parlours of rich men's daughters in the West End and established themselves as a force among women of all classes. The alliance with feminism is another important feature of historical Marxism - amd Eleanor was there when it was first forged.

The very last significant thing that this remarkable woman did before she died (she left behind a set of edited minor works by her father that showed him in an unusual and interesting light, as historian and philosopher - one last act of filial devotion) was to translate a work by Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism. This is significant in all sorts of ways. First, it suggests an intuitive recognition of the coming significance of Russian Marxism. Eleanor's translations, with two exceptions, had been literary, not directly poitical - Flaubert and Ibsen - and of the two exceptions, one had been by a man she had loved and nearly married. (As we shall see, this is a matter of some significance.) To take this trouble on behalf of a little-known theorist, and a Russian to boot - Karl Marx had denied that Russia could experience a workers' revolution - suggests unusual interest.

It also places a firm underline under Eleanor's lifelong opposition to the Anarchist ideal, which Plekhanov's book is meant to demolish. Eleanor had left the Socialist League that she had had a large part in founding when, in an amusing reversal of common Marxist practice, it was taken over by an anarchist faction. The one point in which the devoted Eleanor - who had acted as her father's secretary when she was barely sixteen - did not innovate or reverse her father's practice was the rejection of anarchist theory and practice; and that was the one area in which Marx was indubitably right. They both saw that there was no future and no practicality in the fad of Anarchy, and in fact one of the most significant narratives of the nineteenth and twentieth century is the complete practical failure of this movement thus far. (Its latest incarnation, Ayn Randism, still does seem to have some life left in it, but I, personally, do not forecast any success.)

There is not one of the areas of significant force and success of Marxism - its connection with the intellectuall class, with mass trades unionism, with Russia, with feminism, and its tradition of organization and refusal of anarchist methods and goals - which does not bear Eleanor's signature. You don't need to love Marxism to see that this woman played a major part in Western history - a part that is still badly underrecognized and underappreciated. And unlike her father, some of her contributions - especially in the field of the arts and of trades union organization - were positive as well as significant. The great theatres of London owe her something, as does anyone who ever revelled in a performance by Lawrence Olivier, Alec Guinness, or Vanessa Redgrave. And one can't blame her for idolizing her father and thus promoting what was, remains, and will remain, a pestiferous and destructive philosophy.

In fact, I would place her next to her contemporary Nietzsche, not only for the practical importance and impact on modern politics of both, larger than that of any other intellectual; and not only because both clearly suffered from serious family-related issues and from a Prussian family heritage; but also because the ends of both, had anyone paid attention to their meaning rather than to their externalities, deliver the most shattering and devastating responses to the theories they had so brilliantly and effectively pushed. In their cases, their deaths really are a criticism of their lives; an unanswerable criticism.

As everyone ought to know, Nietzsche, the promoter of the ruthless and dominant Overman, suffered his final collapse - brought about by syphilis - when he saw an Italian cart driver belabouring his unfortunate horse cruelly with a stick. The Prussian philosopher threw the man off, embraced the abused animal's neck, and collapsed, weeping bitterly. From there he had to be taken to a house for the mentally ill; and he was never from then on in any condition to be released, until he died. The story comments itself, and I have no need to enlarge on it.

And Eleanor? Eleanor, interestingly enough, sounds a lot like Nietzsche - and like Nietzsche at his silliest - when she talks about Jesus Christ: a whiner, a loser, a bad example. She was, of course, brought up in an atmosphere of aggressive atheism, and in this as in everything else she never consciously broke with her father - even as in so many areas she innovated on or reversed his practice. One wonders how well her views went down with her English Socialist allies, of whom nearly every one was Christian or at least had Christian roots. However, atheism, whatever its relationship or lack thereof with English Socialism, certainly did bring her the man of her life.

Eleanor's life was dominated by three men: her father, whose work she so devotedly and capably continued; Hippolyte Lisagaray, the obscure French revolutionary and Commune of Paris survivor, whom she would have married - even against her father's will - had she not eventually come to agree with her father that Lisagaray was really too old for her; and Edward Aveling, whose name she took. The facts show that Eleanor (whom everyone called "Tussy" for some reason) was a devoted and passionate woman. When she fell in love with Lisagaray, she spent years breaking down her father's understandable opposition, before concluding by herself that marriage with a man 17 years older would not work; and even so, twenty years later she lent her translating work and the prestige of her name to have his Histoire de la Commune de Paris, 1871 published in English - hardly a small favour, whatever ideological excuses may be given.

If you look Eleanor up, you will most often find her, not under "Marx", but under "Aveling" or "Aveling Marx". That was the name under which she signed her work and her translations, and it seems clear that it was the name by which she wanted to be known. You may have noticed I refuse to do so, and that is not only because they never actually married, but because Aveling was the scum of the earth, altogether unworthy of her, and the direct and immediate cause of her death. And if this sounds too Victorian for words, I will answer that Aveling really was, in every way, the quintessence of the weak, womanizing scoundrel of Victorian fiction. The son of a Congregational clergyman, he experienced a revolt against his father's religion which evidently extended to all matters of financial as well as sexual morality. Notorious for borrowing and never returning even the smallest sums of money, suspect of having embezzled the funds of the Socialist League - it certainly was near-bankrupt when he left - he also is said to have had numerous affairs, without ever managing to father a child. He married an heiress, and left her after a couple of years without obtaining a divorce - he said, because she couldn't stomach his atheism; her friends said, because he could not get at her capital.

It was immediately after this that a vindictive fate, and a common faith in atheism, threw him in Eleanor's path. And how and why this hard-working woman, already expert in worldly matters beyond most of her contemporaries, so shrewd in political matters, so capable of forming lasting friendships and of gaining widespread affection - as was seen at her funeral - should fall for someone who literally was incapable of doing anything except writing atheistic pamphlets, is something that simply baffles understanding. As I said, Aveling had never obtained a divorce from his first wife; "Tussy" made the same mistake that many women have made before and since - she moved in with him without any formal bond. How she felt about the relationship is sufficiently shown by the fact that she took his name; and being herself loyal and devoted by nature, how was she to understand that he would prove the exact opposite?

One may speculate that Aveling might have been less destructive and damaging if he had, in fact, managed what he seems to have tried - married a rich woman and lived the life of a drone on her money. But I doubt it. There was something about his scoundrelism, like his compulsive habit of borrowing money - even from his poorest friends - and never repaying, that went beyond mere dishonesty and hints at some compulsive self-destructiveness, that would sooner or later have brought him down in some ruinous fashion, and probably have taken others with him.

Atheism led Aveling to Eleanor, and Eleanor led him to Socialism. Before they met, he had shown no interest in politics (he was a zoologist by training). Her enthusiasm quickly rubbed off, and he found there was plenty of work to do. To be fair to him, he did have a ready pen, and he co-authored all of Tussy's original writings on the workers' movement as well as publishing plenty in his own name. That represents a lot of work, and suggets that he was no drone - whatever Tussy's part in the origination of his writings.

In 1898 came the smash. Eleanor was now 43 - not old age as we understand it, but certainly a bad time for a woman to discover she has a younger rival. And not just a rival: Aveling, whose first wife had now died, had secretly married a young actress. (It had to be an actress, for the Victorian cliche' to be complete!) He briefly dumped Tussy for her, but came back when he found he had mortal kidney disease. She nursed him for a little while; then, one day, she falsified his signature on a prescription, bought cyanide from a chemist ("for a dog", said the falsified prescription), made sure she was alone in the house so that nobody should be able to rescue her, undressed, lay down in bed, and swallowed the poison.

That was it. The intelligent, far-sighted woman who had done so much to promote dialectical materialism, and who had actually done some considerable good in its service (though the goal remained disastrous), was destroyed, led to destroy herself with the most horrendous care and deliberation, by something that her father's philosophy treated as an epiphenomenon of socio-economic relationships, bound to wither and die when the new realm of freedom rose upon the earth: the love of man and woman, the exclusive relationship of marriage, the lifelong consecration of a man to a woman and a woman to a man. And may God have mercy on her soul, because no suicide ever had a higher heap of excuses for her sin.

My story began with the eleven lonely people at the burial of Karl Marx; it ends with a vast crowd at his daughter's cremation, speeches from no less than seven orators, and the preservation of her ashes as a kind of sacred relic by successive Marxist bodies (they were only interred in 1956, I believe). Aveling, who was dying of kidney disease, outlived her by only a few months, but he was (deservedly) treated as a pariah by every other Socialist in England, as well as by many people who were neither Socialists nor atheists, but who agreed that he had been the cause of his wife's death.