Trine (Katrine) Michelsen, 20.1.1966 - 19.1.2009

She came into the world in the depths of winter, and in the depths of winter she left; in the worst winter in decades, one day short of her forty-third birthday, as if the ghastly producer that had set the stage for the last few years of her life had wished to underline how unfulfilled, in every human sense, the life of this angelic beauty had been. Trine Michelsen’s death has been national news in Denmark and took up quite a remarkable amount of website space on several news organizations; and the extent and content of the reports have led me to rethink my view of the woman with the Silver Angel’s face. This is meant as an account of what I think I know of her now, and of why I feel rather ashamed of the odd superior remark I may have dropped in the past.

I shall start from the farewell letter she wrote to be read at her funeral:

Dear all of you whom I have loved, and all of you I love! Without you, my life would have been in vain , You have taken me to where I am. And where we have we had fun together, my life has been filled with laughter - smiles - as well as with all that sorrow and pain. Incomprehensible pain for which I do not have any words. Maybe that was just my fate.

I have no idea how this should be, and where I am going! But I know with certainty that I am going to miss every single one of you, so much, and that I will smile down to you forever. It can only be hoped that we see that most lovely place one day!! You must not find it wearysome, that life goes on. But keep me in your heart, so that I can live on till you one day forget me - or come by, where I am.

I miss you already. But now I can do no more. I am not afraid. Life has done me so much evil , and I've cried so many tears. Where I am now, I will be able smile the whole time, so do smile up to me some time! Take care of each other! All together! It was good to have known each other, and enjoy life , while you have it.

I love you all so much. Thank you all, thank you for sharing your lives with me! Smile and love for ever.

Trine

This is not, of course, the writing of a philosopher or of a professional speechwriter. The abuse of exclamation marks - which I have actually reduced from the original - suggests that her style models included old-fashioned comics scripts (when editors instructed writers to use exclamation marks as much as possible, because poor printing meant that the dots of periods might not be readable). And there is a contradiction between her feeling that life has done her so much evil, and the invitation to everyone else to enjoy it, which could easily have been resolved, but was not. The emphasis on the act of smiling is also rather strange to me, though not unwelcome. But I find it deeply sincere, affecting, and noble in feeling and intention. There is nothing that could be described as self-pity, only a moment of bewildered wondering at the reasons for her suffering; and her suffering is indubitable, a fact, which only hypocrisy could deny. On the other hand, the sense of love and gratitude for all who had been her friends is overwhelming.

Friendship is the keynote of Trine’s life in the accounts of those who outlive her. “It was as though nothing had happened to Trine, when she became ill. She had always been the sweetest, most generous person you could imagine; but that part of her only came out better after she was struck by cancer. She paid more and more attention to little things; and in spite of the fact that in the meanwhile she was absolutely terribly ill, she was so capable to give so incredibly much to everyone all round her. She had so much love to give, it is hard not to believe that Trine was an angel,” says Lisser Frost Larsen, one of Trine’s best friends, fighting a losing battle against tears as she speaks. Another newspaper reports her simply as saying that “Trine was an angel on Earth.”

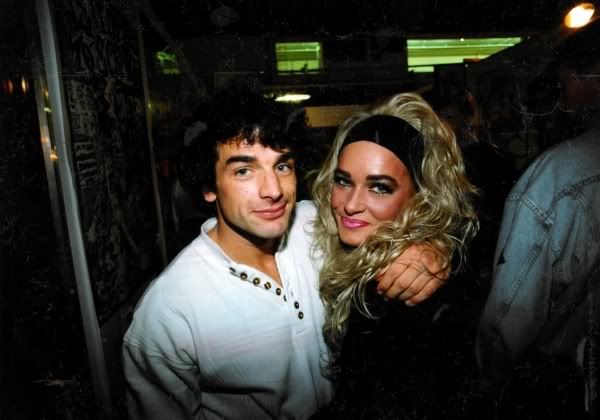

Trine Michelsen and Lisser Frost Larsen

While this is her best friend speaking, dozens if not hundreds of witnesses agree. In Denmark, hundreds of people seem to have known Trine and have had reason for love and gratitude, even in casual encounters. The word “angel” and its derivatives recur to the point of becoming a commonplace. “Thank you for taking me under your wing when we were in North Jutland together,” says Bettina Madsen in a commemorative Facebook group. “I was glad to find myself together with Trine in Spain (14 days, spring 2005). She gave out an incredible sense of warmth and happiness when we were with her. In spite of her own disease in the trunk and shoulder, her energy was incredible. I know that she is in a good and pleasant place now. It is I who thank you, Trine, and send my thoughts up to you,” says Rikke Pedersen; and Michael Poulsen just: “Thanks for all the good times.”

Her illness made her not only more generous, according to testimony, but braver. She was a light in the cancer ward. "Through her whole period of sickness, she has been quite unbelievably brave and positive.... She encouraged defiance in everyone near her and was nearly always in high spirits.” As it happened, another female Danish celeb - TV hostess Kamilla Bech Holten - was dying of the same illness, and Trine is reported to have given her strength and comfort in her last days. Her humour and wit were so well known that some of the headlines describe her as “model, actress and humourist”, even though she never, to my knowledge, did any comedy professionally; but in this context, it becomes clear that they were more than just wit - they were her way to pass on to others some of her own enormous courage.

But even this quality of encouragement and positivity that shone like a star in her last days was not, as Ms. Larsen indicated, only a feature of those days. Jan Petersen, who knew Trine when she was about eighteen, posted an account of her in Facebook that said pretty much the same: Trine was a person who would not let you be sad or downcast - she was relentlessly positive, and would strive to make you feel the same. And this, if you please, was at the time when she was breaking with her father. “Trine always found it easy to make friends, and I was one of them; alas, only for a couple of years. At that time Trine lived at home with her single father Ole, and I was introduced by her friends Sanne and Anja… Trine hated everything that was grim or negative, so you had to be a bit careful! : ) To the contrary, Trine was enormously positive, clever, even a bit sly… you could certainly talk things over with Trine in great depth, so long as you followed her rules. Trine loved to call at my home, to watch Bamse & Kylling on Sundays. We exhausted ourselves laughing… : )

“The year must have been about 1981 and Trine was about eighteen. Even at that time , she was unimaginably beautiful and got herself great attention through countless parties. She always wore something light and provocative. Trine was a highly sociable body, and formed bonds among us others, as well as with new friends. I have rarely met a personality like Trine, where a hug was a daily event in the midst of a desert of rejection. It is no exaggeration, and others shall attest, that, that Trine changed my view of the social contact with other people, into something I could bear and apply. We lost touch later, but we would meet by chance here and there, and remained good friends…”

In other words, kindness and a positive attitude were not things she learned under the stress of disease. The eighteen-year-old Trine was just as kind and positive as the forty-year-old cancer victim. It was other things that had changed. Jan Petersen hints that one could have trouble with the younger Trine if one did not follow what he calls her rules; Lisser Frost Larsen’s Trine does not sound so ready to lay down the law. It sounds as though the intervening years had blunted her certainties, without doing anything to her generosity and courage.

Not, of course, that she saw herself as particularly brave or generous or remarkable. She said that “You are so strangely alone, when you are ill. Half the time I am mad at God and asking, What have I done?” And in her final message, she thanks her friends for carrying her along, without realizing that it was she who was carrying everyone else. And while amazingly energetic, she was not superhuman. Henrik West, a friend she made in the Montebello nursing home in Spain in the years of her illness, claims that towards the end Trine did not have the energy to cope with all her friends: "she rather hid herself during the last year; she answered no texts or phone calls, and sometimes she would not open the door when someone rang, because (?she felt dirty?) with her illness. Only the very closest were with her". This may have something to do with the emphasis, in her last words, on thanking and expressing her love for every one who had ever been her friend; perhaps she felt she had not been able to thank them as they deserved in her last days.

This is a chryselephantine picture, all in white and gold, the picture of a woman both selfless and brave well beyond the point of heroism; only in Jan Pedersen’s account of her eighteenth year contains any suggestion of shadows - a certain spikiness, and a hint of promiscuity. Of course, it is good manners to speak only good of the dead; but this does set up a certain kind of cognitive dissonance. How, in short, does this living female saint, this - the word used over and over again by so many who knew her - angel, remembered with love and gratitude by hundreds of her fellow citizens, agree with the softcore starlet into dope and - according to her own account - destructive and violent men, who married a bank robber and who at one point had to have her teeth expensively remodeled because the drugs had taken such a toll? The two pictures are not exactly contradictory, but they certainly demand a certain amount of reconciling.

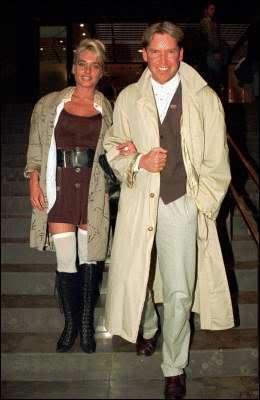

At least one of the issues can be disposed of at once. Rodrigo Oberreuther, her Chilean-born former husband, may have been many things - boxer, convicted bank robber, jailbird - but one thing is certain: in his youth, he was a man of astonishing beauty. With his black curls, strong features and large eyes, he would have been remarkable even in Italy - the living image of Renato Carosone’s ladykilling Sarracino; in Denmark in the eighties he must have had the added value of exoticism. There is nothing strange about a loose, wandering star like the young Trine falling for someone like him before he was fingered for a 1,200,000 kronar robbery and jailed; while I find it rather typical that she wore his ring and kept in touch for as long as he was in jail, and it was only afterwards, in the early nineties, that they definitely broke up. It was also typical of the perky and humorous side of Trine that as late as 1998 she used his name and a thumbnail description to discourage some over-fresh male fans.

Rodrigo Oberreuther and Trine Michelsen in the eighties

(Even so, Oberreuther turned up at her funeral - to the reported disgust of some of her friends - saying nothing to press or public, but sitting near the front and leaving, after the ceremony, a single flower on her grave. He also had a public embrace with her father, Ole Michelsen. The least that can be said of this is that for him, as for many others, Trine must have been easy to love and hard to forget.)

Other issues can be read two ways. Trine got into a habit of drugs, yes, but then she got out of it too - and anyone who has ever tried to kick a bad habit must realize how hard that is. When, in the wake of another failed relationship, she feared she might relapse, she checked herself into a drug clinic. All that we know about drugs, destructive relationships, ruined and remade teeth, come from things she herself has said. One might speak of bad habits, yes, but also of the courage to admit them in public and face them.

But these are comparatively lesser matters. The issue of pornography, on the other hand, is one that runs through her life, that dominates her public image and her private life - the reason why most of us ever heard of her in the first place. And its incongruousness does not diminish with knowledge. Look at Trine herself. Here is a clip of an interview she released about her cancer - . I know you can’t understand Danish, and neither can I; but that allows us to pay attention to everything else. Listen to her voice, soft, even, yet expressive; look at her stance - courteous, attentive, occasionally bending her head to the host as if to be sure to catch every word; pay attention to the way that her answers always come a second or two after the question, showing that she is giving thought to each of them before she speaks; look at her expression, attentive, gently serious, sometimes suddenly folding into a smile by turns sweet or sparkling; and last but not least, contemplate her still undiminished beauty, even in a visibly aged face, the result of the meeting of extraordinary features with a truly impressive personality. Would you say in a million years that this thoughtful, solicitous, quiet-spoken little person is discussing the disease that is destroying her from the inside, that will probably kill her soon, and that is in the meanwhile daily inflicting unimaginable pain upon her? Would you Hell. And if you knew it in advance, you would probably say, as I do, that this is one of the most touching, affecting, heartbreakingly brave things you have ever in your life seen outside of a concentration camp or a death chamber. But, as well: would you ever imagine her profession? And please, no glib generalizations of the “we can’t make generalizations” kind. Would you ever think that a woman who is in every way so obviously a lady by nature and character had ever earned her living by taking her clothes off? The two things simply do not agree. Softcore porn is innately vulgar; and vulgarity simply does not agree with what we have seen of her in her interview.

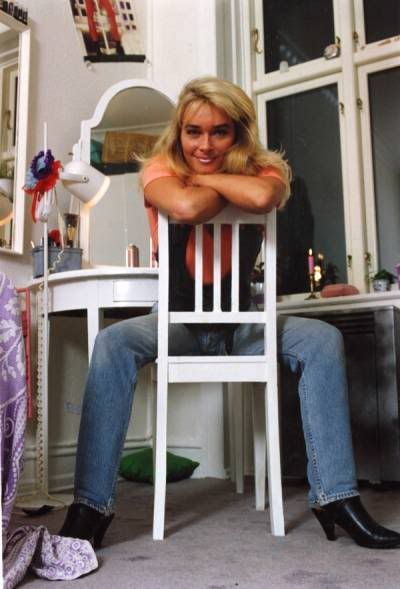

It does, however, agree with a different and curious feature of her character: her really fantastic and almost supernatural aptitude for fashion mishaps of epic proportions. Her clothes in the interview were not very well chosen, but as compared with her usual gear, they might as well have been Armani worn by Kate Moss. I beg her shade pardon, but to say that Trine was a one-small-woman walking, taking, photograph-posing fashion disaster area - well, it is no more than the truth. She certainly verifies DL Sayers’ old jeer at naturists: “If you cannot be naked, be as badly dressed as you can, I suppose.” Italians who have been there will tell you that the borders of the Empire of Good Taste, where fashion is concerned, run well south of the Danevirke; but even by Scandinavian standards, Trine was exceptional. She ordered her own outfits, and the results are very much in the “so bad it’s almost good” category. Whether dressed as a kind of galleon, or extravagantly missing the point of biker gear (bikers do not wear white, Trine, for many good reasons to do with oil, dirt, flies and smoke; and what is with the puffy arms?), or apparently taking Captain Harlock as a fashion model to imitate, she could have at any time have made the top in the Top Ten Worst Dressed Women, if the journalists who compile such things had ever heard of her.

When Trine did not try, she was stunning. In a pair of jeans and t-shirt, she could blow away any woman you care to mention. When she tried… well…

This complete absence of taste is not merely a matter for snarky bloggers. It can be shown to have at least once had potential results for her acting career (theoretical though the issue may be now). Trine attended the Cannes film festival as part of the cast of Lars von Trier’s The Idiots (Idioterne). This was her first serious break in the film business since La Bonne, and there could not have been a better opportunity to become known as an actress. Cannes is the second most important occasion in the movie business after the Oscars, and especially friendly to von Trier (who was and remains by far the best known Danish director abroad), who had previously won a couple of awards there; and the movie, following on the critical and commercial success of his Breaking the Waves, was widely looked forward to. It was an event: even those who knew they would hate it looked forward to the opportunity of being elaborately and loquaciously disgusted.

At such occasions as Cannes and the Oscars, star actresses walk a very fine line between showing as much flesh as they possibly dare and keeping a very strong hold of glamour, style and elegance in dress. Backless dress are frequent - to show, or pretend, that a woman of thirty or forty has no need for bras - and sexual suggestiveness virtually universal; but it has to be classy and elegant. The journalists sent to cover such events are experts at destroying fashion faux pas, and indeed part of the fun after every festival is running a comparison of fashion successes and failures. And mind you, Trine (who had, it seems, endeared herself with the whole crew by her humour and her cheerful and willing attitude) was allowed to walk in at the premiere hand in hand with von Trier himself and at the head of the cast, never mind that von Trier had overcome his famous fear of traveling especially in order to be there.

Lars von Trier and Trine Michelsen, Cannes, 1998

Trine blew it twice over. Her black-spaghetti dress probably showed less flesh than some, but it was inescapably tarty; and, even worse, she had herself photographed on Cannes beach, naked except for a bikini bottom. That is a custom at Cannes - but for publicity-hungry starlets and glamour models, not for stars. In the eyes of the Cannes cognoscenti, she as good as qualified herself as nothing else than the softcore model that she was already known as. A few keener-eyed reviewers described her as “the best thing in Idiots” (the reviewer who wrote this exact sentence had never heard of her before), but in general discussions of the movie tend to leave her out.

(Ten years later, Lars von Trier and several cast and crew members turned up for her funeral, and so did Søren Fauli, who had directed her and starred opposite her in Antenneforeningen.)

Now, while I cannot take the view that every aspect of her terrible taste in dress has to do with her attitude to sex, nonetheless vulgarity - and specifically absurdly overblown cleavages - is a major feature of it. It certainly was in the black spaghetti dress. And that goes with a couple of other facts. Trine was known to be obsessed with her breast size, and photographs prove that she had her breasts modified more than once, in order to come closer to the page-three standard. Likewise, she was obsessed with tanning; in spite of the fact that anyone who has seen Antenneforenigen must have seen that her natural skin tone has a pearly translucence that exalts the beauty of her features, her cheekbones, her green-gold eyes. Again, she used outrageously bad blonde wigs. She was a natural brunette, but could look well with the appropriate blonde colour - as seen, again, in Antenneforenigen; but some of the wigs or hair colours that she wore, especially in the nineties, seemed designed to scream their falsity to the heavens.

The picture is clear. She wanted to be blonde, tanned, big-breasted. What a strange, sad, little ambition. With the face of an angel, the talent of a star, and the figure and presence of a heroine, her ambition was to look - at best - like a Playboy magazine blonde; which was not going to happen in any case. She had an ambition to be - less than she was.

I think it is this issue of ambition that is really central - even more than the matter of sex as such. And to make clear what I mean, let us make a comparison with a woman who is in more than one way easy to compare to Trine: namely, Katharine Hepburn. Trine’s sex life often ended up in the papers; but considering the revelations made since la grande Katharine’s death, one might say that, of the two, it was the American who had the wilder sex drive. Before being tamed by Spencer Tracy, she could not be safely left next to a handsome man or woman - although she capriciously turned down John Barrymore, who was understandably miffed. Indeed, she was notoriously bisexual, which Trine was not; and as to her approach to relationships, it was her own father who politely compared her to a charging bull.

The difference was that Katharine Hepburn’s ambition, as opposed to mere lust, was focused like a heat-seeking missile on one single purpose: to be the finest and most successful leading lady she could be. To get there, and to stay there, she fought formidable obstacles and overcame terrible humiliations. Early in her career, a director who had it in for her for sexual reasons (one of the by-products of an “adventurous” sex life) deliberately sabotaged her performance, leading to disastrous reviews including Dorothy Parker’s legendary “She has run the gamut of emotions from A to B.” (According to Garson Kanin, Parker later regretted that quip and would say of Hepburn that “I don’t think there’s a finer actress anywhere.”) She picked herself up, dusted herself off, started over again with a voice coach, and in an astonishing short time she was playing lead in Broadway and Hollywood. A few years later, however, she was practically driven from Hollywood by concentrated idiocy from distributors and producers. Her reaction has gone down in movie-industry folklore: she developed herself an excellent play from a couple of friends, made it the biggest theatre success of the year, and - when Hollywood came sniffing for rights, they found that she owned the lot, and she was in a position to dictate exactly how and by whom the movie was to be made. She did so in the most autocratic style, and the result was The Philadelphia Story - a movie that has not aged in more than sixty years.

One thing worth noticing, however, is that, having got herself to the position where she could for all practical purposes produce a movie - whose-ever name was on the producer tag - she did not insist. Her occasional reported talk of directing this or that piece seem to have been no more than casual spurts of her restless intelligence; at least, she did nothing to pursue such ideas in the way she went after a favoured part. She really and truly wanted to be an actress, and her epic campaign of reconquest with The Philadelphia Story, though it remained a model for every show business professional aiming to take control of their career, proved in the end only a means to that end. Katharine Hepburn Productions Co. never materialized; but Hepburn herself went on acting as long as she could physically make it, even when her body was hammered by age and illness, and acted her way to immortality.

Ambition gets a bad rap these days, not least thanks to our beloved JKR - who really ought to have given a bit more thought to Slytherin than she seems to have. We are all aware of the bad kind of ambition - the inadequate who flatters his superiors and steps on his inferiors; the sneak who worms his way into favour; the demagogue who flatters his audience and encourages their worst sides. But the ambition that has shaped history has more often meant the burning need of people who have an instinctive sense of their potential, to actualize that potential, to turn it into success and achievement. When Ricky Martin was asked what he would have been if he could not have become a musician, he answered without missing a beat: “The most frustrated person on Earth!” The potential for an activity is often felt before learning it, and the learning process is part of the process of fulfillment. (And it is interesting that the person who asked Martin that question was Sir Steve Redgrave - the greatest Olympian Britain ever had, and a classic instance of fulfilled ambition.) I think I can say that the consciousness of unfulfilled potential is one of the most horrible things in human life, an especially refined, justified and debilitating form of guilt.

An endearing visual joke: some photographer thought Trine so small that she could be carried around in a beach bag!

(It is for this reason that I love to follow the successes of my younger friends in the professions they pursue. cette_vie, kikei, sanscouronne, becomethesea, tashmania, aphoenix2007, and all the rest - do not let anything come between you and your ambitions, which are legitimate, honourable, constructive and brave, and do not let anyone and anything make you forget who you are and why you are working, struggling, fighting. And a special word to solitary_summer and to kennahijja: believe in yourselves - or else your already towering achievement will be discovered ten years after you are dead and do nobody any good except the writers of art and literature histories.)

On the other hand, ambition achieved, ambition on that level, has a common name - and that name is genius. A work of genius is the work of someone who has made successful use of an uncommon potential. That is, as I have argued elsewhere, genius does not refer to an exceptionally high order of intelligence, or even of talent; and indeed, it is possible to have stupid geniuses - my usual examples being Niels Bohr, Corneille, the Douanier Rousseau, or Bruckner. And the socio-cultural environment has as much to do with the rise of genius as the potential of the individual. A culture - meaning by this both the artistic and the anthropological meaning of the word - can squash, misdirect or pollute ambition to the point where it becomes impossible to imagine intellectual success, or conversely so energize it that small towns such as Athens or Florence become breeding grounds for genius on an absolutely unbelievable scale.

Now take Trine. Her main ambition was to be a movie actress. I do not think that anyone can doubt that she had the talent. She had the right face - not just beautiful, but unbelievably photogenic, full of dramatic planes and shadow, and with positively luminous eyes. She was the daughter of Denmark’s leading movie critic, and must have grown up living and breathing cinema. Her energy was by all accounts unbelievable, her attitude excellent - a desperate requirement in the collaborative environments of stage and screen - and her personality pleasing. Even her reported promiscuity can hardly have been an issue in that particular professional environment. Indeed, if it were possible to breed human beings for genius, in the old eugenistic program, I have no doubt that the result would be something like Trine; even her small size means a more economical build, and more results for your buck.

However, Trine, as an actress, achieved very little. We are not even speaking about a case of tragic early death such as Montgomery Clift’s or James Dean’s, still leaving behind bodies of work impressive enough to let us see them as major figures. Trine made only three movies in her life that are worth anything except dumping, and none of them - not even The Idiots - have the kind of stature that would insure that she would stick in our memories. And while a death at 42 is young, it is not too young in a business in which women peak in their twenties.

What went wrong was that her career took a wrong turn at its very beginning. Trine sought for her movie career in Italy, without, I imagine, realizing that the Italian movie business had hit a nadir. The giants of the past had died out, and except for the occasional movie from Antonioni or the brothers Taviani, the level of production was decidedly low. Scoundrelly sex comedies featuring the likes of Lori del Santo (known abroad for her tragic affair with Eric Clapton) ruled across the board, to the disgust of critics and fans, and the rise of private TV channels had not raised the overall level. Trine’s first movie (La Bonne - English Corruption) was with a man with claims to be an auteur, Salvatore Samperi, a crafty and conniving director who understood that in order to smuggle pornography on to the main market you had to dress it up as culture. Unfortunately it was with that one that the critics, after being led by the nose for fifteen years, finally found him out, and the reviews were universally negative. He had made the gross mistake of adapting a play by Jean Genet, France’s poet of evil; and the universal view was that he had thrown out everything valuable in his source and exaggerated everything that was merely pornographic. I was in Italy at the time and I was dismayed. I was and remain not sure that the movie was really so far below its original, but it was a good excuse for the critics to finally shake off more than a decade of bewildered complicity. They called Samperi’s prettified pornography by its name; and Trine’s excellent performance went unnoticed in the general (and not undeserved) execration of the script and the attitude of the movie.

Trine’s subsequent films had no claim even to the fraudulent attempts at auteur-ship of a Samperi. The least shameful, Spettri, has the sorry distinction of being the bottom of Donald Pleasance’s career, and of having a script that treats Italy as if the author had never been there. Naturally, there has to be a sex scene. The remaining couple are better left unmentioned; nobody unfamiliar with Italy in the mid-eighties will at any rate ever believe that they were made.

On the side of the producers, it is clear that Trine had been written down as another Sydne Rome or Maria Schneider, a young foreigner just ripe for exploitation. If you think Hollywood a sink of iniquity, you ought to try Cinecittá some time. I am a patriot, but hardly blind to my country’s flaws; and there is something about my countrymen that means that, when they are scoundrels, they are scoundrels with a kind of uncomplicated willingness, a cheerful and sometimes downright sentimental selfishness, an undisguised and heedless greed, that make everyone else look honourable. A young lady from an upper-middle class Copenhagen home was certainly no match for such a pool of sharks. But as for Trine, her choice in movies brings up once again the matter of her taste. And of its connection with vulgarity. Surely no actor would accept such roles unless they were utterly and totally cynical and jaded - which she was not even old enough to be, even if we could ever imagine her as such - or else unless there had been a total failure of taste on their part.

Trine was well known in her native country. A local restaurant named a dish of smorrbrod in her honour

I spoke of culture in the artistic sense choking achievement, and here, I think, we have one instance. Trine had grown up in the seventies and early eighties, in a household that lived and breathed cinema. The year after she was born, Hollywood threw the Hayes Code overboard; one year later, the first artistic sex movie, I am curious - Yellow, was made in Sweden, just across the sea. In the time of her youth - a time I remember well - one of the great ideas of the dominant culture was the normalization of sex, the transformation of pornography into a mainstream genre. This explains, among other things, the puzzling phenomenon of the movie Deep Throat - an abominably shot virtual home movie made by a bunch of chancers, which had a quite unbelievable amount of positive publicity and reviews. Quite simply, the reviewers wanted to see pornography become art, and they saw it where they wanted.

I do not have to argue that Trine believed in this idea; every step she took in every moment in her career proves it beyond peradventure. And with the innocent aggression of any eighteen-year-old with brave eyes and all too clear views (remember Jan Pedersen’s mention of the trouble one might have with her, at the time, if one did not follow her rules?), she set out on her adult career by trying to act them out.

It was her bad luck to have come in at the precise moment when the great experiment started to prove conclusively a failure. Sex would not be normalized, and pornography would not become mainstream. The failure of Samperi’s La Bonne was part of that process; it was not just the condemnation of a movie, but of a career - never again would Samperi be taken seriously. And the same process was taking place across the board. However much mainstream culture, even TV and movies, kept flirting with pornography and pushing the line ever further south, the very point, and the commercial value, of their doing so, was that they were clearly skirting the boundary of forbidden things; everyone had instinctively recognized this - at least everyone at the very top, the movers and shakers. And of all of them, it was the villains in Italy, least susceptible of all to faddish ideas and outlandish notions (perhaps the effect of the realistic morality of Catholicism), who understood it first; almost from the beginning, they played porn and near-porn purely for money, and never took any artistic pride or concern to it at all. Critics increasingly recognized it as well, not by admitting it, but by marginalizing all things that were unashamedly pornographic. Pornography remained immensely profitable, but at the price of losing all respect. An interesting symptom, not irrelevant to Trine’s career, is that porn actresses who tried to cross into the mainstream, from Marilyn Chambers to Traci Lords, consistently failed. Producers did not employ them, and critics went after them.

So Trine’s career started very badly. And it was due to a cultural failure to do with the environment in which she had grown, which made it hard or impossible for her to distinguish workable material from pretentious and dangerous nonsense (dangerous to her career, I mean) and which also affected her taste. However, there is another way in which the culture affected her career. Consider Katharine Hepburn, again. What did she do when her career had suffered an almost comparable check? Which it did not once, but twice. She went back, started over again, and on the second occasion actually broke new ground, developing her own material for a stage success, in order to rebuild it. Trine did not. Save for one or two apparitions on TV or minor roles in movies, she did not make one real performance until Idioterne, over ten years after her last Italian work. And why was that? Had she given up? Not at all, not really. It was just that she was being successful, very successful, at another career - “glamour” modeling. She was one of the most in-demand nude models in the world. Between 1985 and 1996, it would have been difficult to pick a softcore mag anywhere without coming across, sooner or later, her pretty undressed figure.

This is the point: for a while, her ambition was satisfied by a lesser kind of fulfillment. And the culture in which she had grown and whose values she accepted without argument would not let her see that it was lesser. Katharine Hepburn came from a rich family, and her father, though disapproving, always made sure in the early days of her career that she should not make bad choices for want of money; but one feels certain that if she had been in the position - like Joan Crawford before her and Marilyn Monroe after - of filming sex for money, she would have treated it as a passing misfortune, left it behind as soon as possible, and if at all possible destroyed the evidence. Trine embraced it as a career. Her culture, the views she had adopted from earliest youth, the ideas that surrounded her and that she breathed in uncritically when she was much too young to know the difference (and I should know, since in my teens I thought the same) - all these things made it impossible for her to understand that it was a blind alley. Crawford and even Monroe had understood that; but in spite of their unruly lives, they had come from a different age. Where commercial sex is concerned, they still had a hold on human reality. We did not, or where we did, we had to regain it by our own unaided effort. It was actually, deliberately kept from Trine’s and my generation, that pornography is, not only socially but artistically and from the point of view of personal fulfillment, an infinitely inferior replacement for the career she had… well, did she think of it as lost, or only as put on hold?

(More in general, the issue of false or partial satisfactions for proper ambition is one that the social sciences have not studied and ought to study. It explains, in my view, many damaging phenomena such as superstition, gang culture, or fringe movements. They are all ways to gain factitious satisfactions in the place of better-grounded ones that are either unavailable or too dear to buy.)

Trine wasted ten years of her life on a lowlife career for which she was as fit as an emerald for the midden of a chicken farm. We are not surprised to find that even there her kind character and ready humour made her loved; but it was a waste. The only good thing that can be said for it is that it was the avenue through which most of us got to hear about her. That she - like many porn actresses and models - developed a serious drug habit which she had to kick, tells its own story; first, about the environment she moved in, and second, about the unconfessed and perhaps unrealized frustration involved in this life. Addiction is nearly always a sign of dissatisfaction - indeed, the ultimate in false satisfaction. Whether or not Trine would agree, I say that it is my view that someone of her quality could simply not be satisfied long or deeply with the kind of success offered by nude modeling; and that the drugs were her way to cope. Or one of the ways.

At this point, I think it only right to touch on that figure of Greek tragedy, Ole Michelsen - the man who outlived both his wife and his daughter. I have a bad feeling that the tendency of what I have been saying has been to place much more responsibility for his daughter’s life path on him than he deserves - especially in the destructive areas. Of course, a habit of secret domestic drinking helps nobody; I have lived with someone who had it (not a member of my family or even of my country, I hasten to add) and I know. But I think that it was other forces that drove Trine on her strange path. When Jan Petersen, in his account, addressed him directly and said, sir, you could not have done better than you did, I imagine that the general reaction might be along the lines of, this is a courteous act of support for a man who has suffered; but I also suspect that it might be close to the truth.

Ole Michelsen at Trine’s funeral

The clue, to someone who had experienced the early eighties, was Mr.Petersen’s mention of an everlasting round of parties and Trine’s gift for friendship. Yours truly was around then, and even he, as sociable as a hedgehog and as attractive as a squashed sausage, went through his share of parties. If Copenhagen at the time was not different from Rome, Oxford, or London, a single parent on a full-time job could have had about as much hold on an active and socially adept teen-ager as a one-handed man on a greased eel. I remember my mother - by no means a weak or silent woman - and my brother! It is very important, for those who were not young then, to remember that this was before AIDS. There were no great fears; except perhaps unemployment. And the future was less important than the present. Even more than any time before or since, it was an age of parties, of teen-agers moving together, of friendship; and a person with the gift for friendship of Trine - or my brother - would find that friendship a very real thing.

We were, in some ways, a doomed generation. Squashed between the baby boomers who occupied the heights of society and a creeping, unmanageable economic crisis that made work precarious and unpleasant, and fed by the kind of culture I tried to describe in Trine’s case, often coming from houses broken by divorce, we had no certain place in the world and no very clear prospects; but we were young, and the long wave of those things lay well in the future. We did not feel threatened - we thought time was eternal; and indeed, the very precariousness of our lives, hanging between broken families, dubious college courses, and unpromising and precarious jobs, led us the more to rely on each other. And we had no real fear. AIDS was soon to cut a bloody swathe among some of us, but in 1985 - I remember it well - it still wasn’t taken seriously. It was seen as this distant thing to do with Haitians. I remember one joke going around in the summer of that year: “What is the worst thing about having AIDS? Trying to persuade your own mother that you’re Haitian.”

I have said elsewhere that people did not take AIDS seriously until the forceful advertising campaigns from the Thatcher and Reagan governments. It may be, however, that the scale of the disaster would eventually have sobered us all anyway. The difference AIDS made was enormous, and later generations, born with it as a background fact, cannot understand it. The illness caused what can only be called a massacre of young homosexuals and drug users in the late eighties and early nineties; often among the most intelligent, most enterprising, most artistic of the generation. But all of us went from a time of friendship, parties and common fun out into a darkness. My ring of friendships at college collapsed for reasons I still do not understand, and my last year there was the worst, without exception, in all my life. My brother broke his neck one day swimming in the Tyrrhenian sea, and only the swift help of his friends saved his life. And here we come to another feature of that generation: to those who, like Trine or my brother, had a gift for friendship, that friendship was real. A cynic looking from outside might only see a pack of teen-agers moving from trashed parent’s home to about-to-be-trashed parent’s home; but when my brother had to struggle for his life, nearly every one of those who had gone clubbing and partying with him stuck by his side - and that was for years. Twenty years later, they are still friends. When he had to be taken to Heidelberg, Germany, for advanced treatment, they came up with him, and, being unable to pay for expensive hotel rooms, pitched a tent in the hospital grounds. This was friendship to people of Trine’s generation. Even in my case, it was seven good loyal friends who tided me over the dreadful time. The myth born from that experience is that of Buffy, that of a group of teen-agers alone against all the horrors of the world with no effective adult help, and relying on each other’s friendship to survive.

Trine lived and breathed this world of teen-age friendships and isolation from the older generation - a world in which the young felt in some ways alone, even cheerfully and happily alone, but alone, and in which they talked only with each other. Ultimately, Ole Michelsen could not have done much to turn his daughter from her path. Her views and experiences were as much from outside as from inside his home, and to judge by Petersen’s account, quite strongly held. She was in some sense doomed to meet with reality, hard and without protection, in a foreign town.

Well, it is certain that she understood the drugs at least to be unarguably bad, and that she took steps to free herself of them. The larger picture is not clear to me. I do not know by what steps she came to return home, to be reconciled to her father (who had been angrily heard to say, in the days of her notoriety, that he could not possibly care less what she did), and to take her first major role in more than ten years. It is certain that she was reconciled with Ole Michelsen before Idioterne had finished shooting, since he accompanied her at Cannes.

Nothing Trine did since represents a conscious abandonment of the porn world or a refusal of its pseudo-values; and at any rate, such would not be her way. She would be the last person in the world to do anything that would amount to dropping or denouncing people she had known, worked with, been friends with. Anyone who had not positively wronged her in a major way would be protected by her innate loyalty. However, both Idioterne and especially Antenneforeningen represent a move away from its values, whether conscious or not. Idioterne is fiercely satirical of the whole world of Danish commonplace values, and its view of sexual freedom, though in-your-face, can hardly be called favourable.

In Antenneforeningen, however, the director and Trine attempted something more difficult and demanding: to present her character and life as a nude model as it would objectively appear to ordinary residents in a Copenhagen block of flats, in fact as the ordinary world would see it. The character of “Kim” was, beyond argument, Trine, and played by Trine. Now oneself is always the hardest part to play, and the reason is that one has to be able to see oneself as others see one; a task impossible without humility (not a natural feature of actors) and an ability to understand the views of others. It was, in my view, an artistic success. The dynamics between Trine and the other characters (played, as I gather, by some of Denmark’s most respected actors) seem entirely natural and consistent. There is one scene stands, to me, for the whole naturalness and credibility of the film. Søren Fauli - director and lead - is coming up a flight of stairs. He has had a row with Kim, and she has been telling her two neighbours all about it. As Fauli comes up, he sees the three women together, and they glower at him as he passes by. Not a word is spoken. Good Heavens, has there ever been a man who has not found himself in the same situation? You have a problem with a woman; and suddenly you find yourself almost slinking past groups of her disapproving friends, feeling their glowering looks like fire, because, as kennahijja once said to me, “women talk to each other”.

Part of the success was in the courageous decision to show Trine as she was, without clinging to the dream of agelessness of the glamour model: a woman in her thirties, with lines under her eyes and incipient folds in her neck. The result is astonishing. On the one hand, the movie would never have worked if Trine had appeared among its other female protagonists - whose homeliness is, if anything, stressed - as some sort of glamorous golden vision of otherworldly beauty; the scene on the stair which I just described would not in a million years have achieved its effect if Trine had looked different in degree and kind from the other two actresses. On the other hand, however, the cumulative impact of her walking, talking, being alive across the screen is simply stunning; after spending a few minutes adjusting to her natural ageing, you come nevertheless to be enchanted, and to say with a Swedish reviewer that “She is wholly wonderful, the world’s most beautiful woman”. By throwing away the pretence of Barbie-doll perfection, Fauli recovered the emotional impact of real, living beauty.

From beginning to end, Trine proves a far more than competent actress, down to her final reconciliation with the Fauli character in true rom-com style. This scene contains one “bit of business”, as I think actors call it, that I have never seen any other actor perform. As Fauli is working on the television set that has been at the heart of the story, Trine places her arms, hands already joined, across his shoulder, then her hands separate, resting one across his shoulder, the other behind his neck. It is not exactly an embrace, not even a caress, but it is the more touching, intimate, affectionate, for being unusual and quite frankly very low in the sensuality scale. It has something of a joining together, since the effect is to have her body come to rest over his; it is the kind of magical moment that we demand, and unfortunately not always receive, as the climax and conclusion of the series of misunderstandings and temporary break-ups that make up romantic comedy. And it is the kind of unique motion, of thinking and acting with one’s body, that only a great actor can achieve. To go back one last time to our term of comparison, the director who knew Katharine Hepburn best, George Cukor, had his own expression for her ability to do similar unexpected and wholly appropriate “bits of business”: “One of Kate’s own-brand things.”

This was, this should have been, only the beginning. Trine had gone back to the activity that suited her most and that had most to offer to her. She had achieved two solid roles, and, in the eyes of good judges, had carried them out well and more than well. But something seems to have happened, and I am not even speaking of the thunderbolt of cancer. Antenneforeningen came out in 1999; the cancer diagnosis took place in 2001. For one whole year, having re-established herself as a believable actress, this energetic, active, talented woman simply vanished from the news pages. One report said that her last relationship, with a schoolmaster, had collapsed, and that she had checked herself into a drugs clinic, fearing that the grief might bring a relapse. Another report at the time of her death said that her greatest misfortune in life had been to be unable to develop a lasting relationship with any man; and while that is a common tabloid topic, in her case it does sound credible. Her strange story with Rodrigo Oberreuther proves, at the very least, that she was capable of falling head over heels in love, of loyalty, and of serious misjudgments.

Whatever the circumstances, and however dreadful they may have seemed at the time, they were only an ouverture. As I said, in 2001 she was diagnosed with bone cancer, a particularly murderous and hard-to-cure version of the disease, and one that loves young bodies. From the beginning, the diagnosis was bad; but Trine fought the disease every step of the way, and it took seven long years to kill her.

From her last shot: in 2005, a sensitive and intelligent photographer called Ditta Valente gives a powerful visual suggestion of Trine’s tragedy.

Bone cancer is a disease that shows what kind of person you are. Most cancers destroy everything except your mind; Trine was conscious, lively, rational and thoughtful to the last minute. Her friend Lisser Frost Larsen remembers their last day together - a couple of days before the end - as a happy, cheerful occasion, although by then they could do no more than watch TV together and talk, and Trine was, in her father’s word, as thin as Karen Blixen (a famous Danish victim of anorexia).

It is my view that Trine took a conscious decision as to what her behaviour would be through her illness, no matter what; and it was an actress’ decision. By which I do not mean that there was anything acted, in the worst sense, about it - anything insincere. But what a really good actor asks him or herself on taking a part is - what shall I be? What person is going to be up there in the lights? Shall I cast, shall I be, the Prince of Denmark as a young hero, or as a Machiavellian politician, or a dangerous egotist with Freudian issues - or something else altogether? Well, this princess of Denmark was called to star in the most tremendous of all tragedies: what was she going, not just to do, but to be, in the face not just of herself but of all her friends, family, and of a nation that knew her well, in the coming years? Was she going to be the cripple, falling back weakly and letting herself be overcome, or the angry victim yelling her fury at the heavens and her sense of entitlement at the earth - or something else altogether?

There was only one possible answer. The talented little actress who never had, and never would have, the opportunity to properly grow her talent into works of genius, took one definite role, a role that fitted her like a glove, that answered all her beliefs and her best experiences - and played it triumphantly for seven years. For seven years, she was the very image of love and courage, defiant, witty, positive, comforting, strong, selfless. I do not hear that she ever missed an entrance or fluffed a line. Much of what I hear about her wit falls into the “you had to be there” category: for instance, on one occasion she is said to have convulsed her father, as they were shifting furniture, with “Hello, this is Copenhagen Elephant Rentals!” But she made people laugh; both people who were dying and people who, if they had not laughed with her, would have broken down crying at her death. She had the face for it, both so beautiful as to want to hug her, and sparkling with innocent fun; and she used that face to the hilt. She believed in friendship, and in positive thinking, and gave those beliefs life and flesh for as long as she had either. She simply excluded from her part all the things which would not suit the mood of the play. The terrible beauty, the frightening heroism of it - a heroism which she perhaps did not even perceive - go with her amazing physical beauty, to create a story and a part so affecting that nobody would have wanted to be without it, though nobody would have wanted to pay the price of her early death.

From her last shoot, by Ditta Valente: walking towards the light.

And so, in the end, and in spite of all the bad effects of the age in which she was born, there is nothing wrong with the chryselephantine image of her. It is an image that she built, that she worked for, not out of ambition but of the desire to bring beauty and love to those she loved, to leave behind something other than a picture of pain, tragedy and an unfulfilled life. The greatest poets of England may rightly be called on to sum up her achievement:

Beauty is truth, truth beauty. That is all

Ye know on Earth, and all ye need to know.

Men say the sun was darkened: yet I had

Thought it beat brightly, even on-Calvary:

And He that hung upon the Torturing Tree

Heard all the crickets singing, and was glad.

Now cracks a noble heart. Goodnight, sweet Princess,

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!

NOTE: I corrected a few wrong dates. Most of my biographical material including all the quotes come from the Facebook group Til Minde om Trine Michelsen and from the websites of the Danish magazines Se og Hor, BT and Ekstra Bladet.