Festivities at the Alamo.

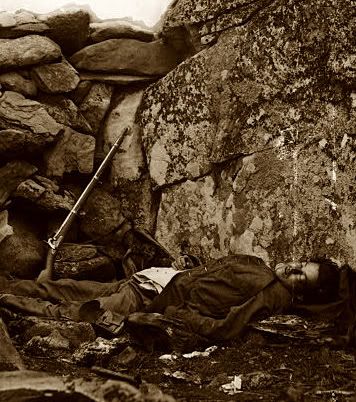

The entire brigade held the decorated soldier down as he gasped for every breath. The puncture was expanding and contracting like a Gatling, perhaps because of the musket round lodged in his right lung. The bleeding was minimal up until the surgeon suggested-to prevent lead poisoning-that the ball be retrieved from the body immediately.

Johnston watched as the men took to his kid brother’s wounds with bayonets and skinning knives. Blood catapulted in spurts from the crowd of amateur surgeons surrounding the nineteen-year-old. His Union uniform once washed and smelling of linens, now held only by threads. It held a burgundy color, drenched in blood and creek water.

The older Johnston collected himself, and took to the creek to fetch more water for the trying operation. When in return, pushing his way through the Billy Yanks, he could hear his sibling’s cries throughout the camp. Looking upon his brother, who had survived so many battles in the war against the secession-who had established an officer ranking at eighteen-he saw a child. As the brigade hovered in panic above him, ashes from the corncob pipes blew into the wound. The camp reeked of grain liquor and horse manure.

With three fingers inside what was now a gaping laceration, the surgeon felt for the ball and pulled it out in its bloodstained glory. The boy bawled into the overcast night; the cavalry stallions neighed in rebuttal.

Mud and creek water replaced the blood pumping out of his wound, as his face grew blue. A lighter shade of blue, however, than that of the Union Army.

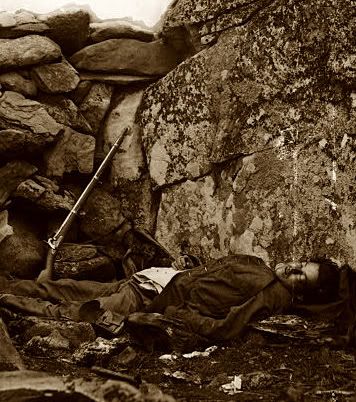

Johnston watched as the men took to his kid brother’s wounds with bayonets and skinning knives. Blood catapulted in spurts from the crowd of amateur surgeons surrounding the nineteen-year-old. His Union uniform once washed and smelling of linens, now held only by threads. It held a burgundy color, drenched in blood and creek water.

The older Johnston collected himself, and took to the creek to fetch more water for the trying operation. When in return, pushing his way through the Billy Yanks, he could hear his sibling’s cries throughout the camp. Looking upon his brother, who had survived so many battles in the war against the secession-who had established an officer ranking at eighteen-he saw a child. As the brigade hovered in panic above him, ashes from the corncob pipes blew into the wound. The camp reeked of grain liquor and horse manure.

With three fingers inside what was now a gaping laceration, the surgeon felt for the ball and pulled it out in its bloodstained glory. The boy bawled into the overcast night; the cavalry stallions neighed in rebuttal.

Mud and creek water replaced the blood pumping out of his wound, as his face grew blue. A lighter shade of blue, however, than that of the Union Army.